It was a humbler, portlier, more emotional Charles Barkley who said goodbye to the sport of basketball April 19, the last day of the NBA regular season and the final night of his roundball career, which had spanned 16 riveting, often maddening, always dramatic years. Barkley had blown out a knee in December, playing for the Houston Rockets in Philadelphia, where his pro career began in 1984. The injury cut short his farewell tour; that night, the onetime bad boy of professional sports sobbed alone in his hotel room, so haunted was he by this final image of himself being carried off the court. Still, his depression didn't keep him from quipping wiseass, as usual: "Now I'm just what America needs -- another unemployed black man," he joked.

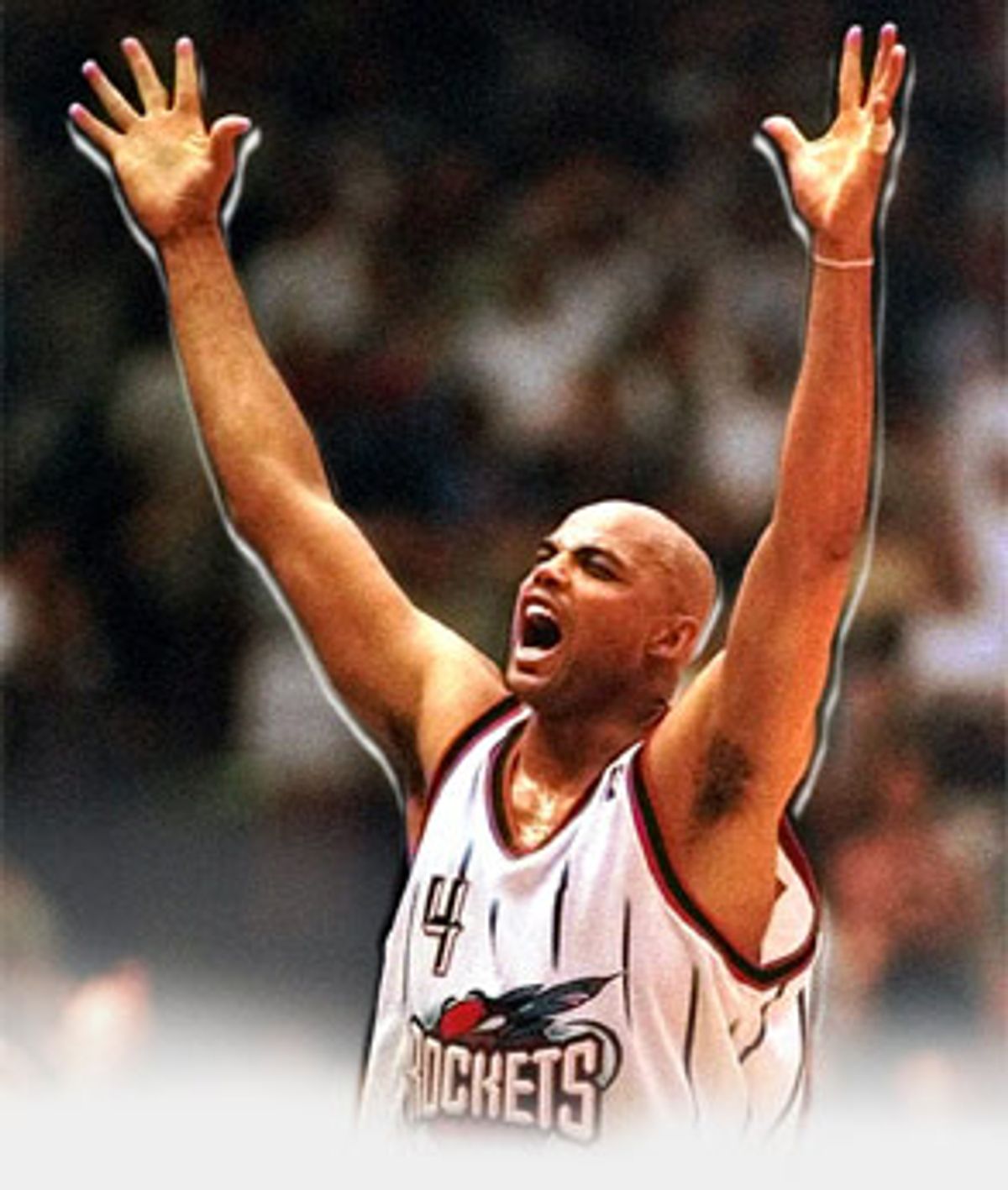

But, post-surgery, he still couldn't shake the vision of sports' hardest worker, a gallant overachiever, helpless. So he rehabbed the knee with an eye on the calendar and there he was on that April night, five months later, standing before a genuflecting Houston crowd that deafeningly chanted his name one final time after he'd plodded through the last seven minutes of professional basketball he'd ever play, making one of three shots. And then he took the microphone, and the Charles Barkley I'd gotten to know a decade ago emerged, the one behind the macho pose. "Basketball doesn't owe me anything," he said, voice quavering. "I owe everything in my life to basketball. I've been all over the world and it's all because of basketball." He paused before finishing by reminding both the fans and his younger teammates to appreciate the moments of their shared passion, because, it turns out, they're fleeting.

And with that, after hearing himself praised by his coach as the bearer of a "heart of a champion," after being presented with a recliner by his teammates large enough to accommodate the girth of a rear end that his wife, Maureen, calls "the size of New Jersey," Barkley retired at age 37. Over the years, he'd transcended sports in a way few others have; part raconteur, part provocateur, the bigness of his persona often overshadowing just how singular a talent he was on the court. There, he was a perennial All-Star, a former league MVP, one of only four players (Wilt Chamberlain, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Karl Malone are the others) to have amassed more than 20,000 points, 10,000 rebounds and 4,000 assists.

What's so startling about the numbers is another number: his height of 6-foot-4. Though nearly a foot shorter than the bruising behemoths he battled under the boards, Barkley often dominated thanks to effort and will. Always a braggart in the showy style of his hero, Muhammad Ali, it was the incongruity between his style of play and his height that once led Barkley to declare himself "the ninth wonder of the world."

Off the court, where he spun quotes and welcomed controversy, Barkley was arguably the most interesting and influential athlete of his time -- maybe since Ali. While others packaged themselves as though they were just another product to be hawked in America's ever-burgeoning commodity culture, Barkley eschewed marketing for authenticity, giving rise to a whole generation of athletes -- the hip-hoppers -- for whom the ethic of "keeping it real" has become a mantra.

In recent years, Barkley has ruminated publicly about one day running for governor of his home state of Alabama. Yet, when I saw him last year, such grandiose plans were far from his mind. He was typically candid when asked what he was going to do when that April night finally arrived and his career came to a close. "I want to learn to play the piano, finish college and get really, really, really fat," he'd said.

Charles Wade Barkley was born Feb. 20, 1963, in the small industrial town of Leeds, Ala. His father bolted early on, and Barkley was raised by his mother, Charcey Glenn, who cleaned white people's homes, and his grandmother, Johnnie Mae Edwards, who worked in a meat factory. Later, Barkley would become the first athlete since Ali and Bill Russell to question the predominantly white sports media's insistence on conferring "role model" status upon young black athletes who comport themselves deferentially, and, after arguing that parents and teachers should be role models, he'd always point out his: "My mother and grandmother were two of the hardest working ladies in the world, and they raised me to work hard," he'd say.

Barkley was not an athletic prodigy. He was, by all accounts, a shy, fat kid. Yet he always harbored a brash ambition. In 10th grade, pudgy and merely 5-foot-10, he failed to make his high school varsity squad. Still, he insisted to anyone who would listen that he was going to play in the NBA. He shot baskets every night, sometimes all night (if he could escape his grandma's strict, watchful eye) and cultivated his leaping skills by repeatedly jumping back and forth over a 4-foot chain-link fence.

A 6-inch growth spurt his senior year led to a scholarship at Auburn University, where he became known as "Boy Gorge" and "the Round Mound of Rebound." At 6-4 and close to 300 pounds, he'd rumble the length of the floor, dribbling behind his back, while taller, more sculpted opponents ran for cover.

The Barkley who was drafted fifth in the 1984 NBA draft by the Philadelphia 76ers bears little resemblance to the confident public man who addressed that Houston crowd in April. Joining legends Julius "Dr. J" Erving and Moses Malone, Barkley was awed by them and by the big, Northeastern city itself. Outside of going to practice and games, he rarely left his rented apartment. He even called sportswriters "sir." He was thankful to be where he was, and not so sure he belonged.

"When I got drafted, I knew I had a God-given ability to rebound," Barkley recalls. "But I never averaged more than 14 points a game in college. So I was just hoping I could score 10 points and get 10 rebounds a game for a few years and make some money to take care of my family." Within three years, he was leading the league in rebounding, and scoring more than 20 points per game.

And Barkley was changing in other ways as well. I first got to know him in 1991, when he'd already morphed into sports' preeminent anti-hero, the flip side of Michael Jordan's crossover-era accommodating persona. The rap group Public Enemy had paid homage to Barkley in song ("Throw down like Barkley!" Chuck D wailed on "Bring the Noise"), seeing his in-your-face game and demeanor as the hardwood manifestation of rap. During a game in New Jersey, a courtside heckler, yelling racial epithets, was turned upon by Barkley, who promptly spit upon his tormentor. Only, as he'd later describe, he didn't "get enough foam" behind the loogie, and, lo and behold, he'd mistakenly spat on a little girl.

It was a national story, of course, and Barkley was vilified. For months prior, Barkley had been persuasively arguing that athletes shouldn't be considered role models. "A million guys can dunk a basketball in jail, should they be role models?" he'd ask, offending the sportswriter crowd who, as he saw it, demanded that he know his place and be a "credit to his race." (His argument would prompt national news when he wrote the text for his "I am not a role model" Nike commercial, a carefully worded polemic that none other than Dan Quayle called a "family-values message" for Barkley's oft-ignored call for parents and teachers to quit looking to him to "raise your kids" and instead be role models themselves.) But with what came to be known as "the spitting incident," Barkley had indeed been found guilty of conduct unbecoming a role model.

I was a law-school dropout at the time, a sports fan who was fascinated by Barkley's ballsy media critiques. I wrote a column in a city alternative newspaper, saying that, of course, Barkley ought not to have spat on someone -- but that he was saying some things we should hear, too.

On the day the piece ran, my phone rang; Barkley was calling to thank me and to invite me over to talk about topics nonbasketball. He was distraught about the spitting incident, shattered even, because one constant over the years has been Barkley's affinity for children. He has long been one of the nation's most generous celebrities, often focusing on children's charities, though it's always been done with one caveat: that no publicity attend his good works (a rule he finally broke last year when he gave $3 million to Alabama schools).

Children don't judge with the venom of adults, he'd explain. And it was that venom he was trying to understand then, in the fallout of the spitting incident: "I think the media demands that athletes be role models," he told me, "because there's some jealousy involved. It's as if they say, this is a young black kid playing a game for a living and making all this money, so we're going to make it tough on him. And what they're really doing is telling kids to look up to someone they can't become, because not many people can be like we are. Kids can't be like Michael Jordan."

Barkley grew even bolder, more in-your-face. He'd inherited leadership of the 76ers from the courtly Erving, and distanced himself from what he saw as just so much kiss-ass demeanor. He began conferring with Jesse Jackson and labeled himself a "'90s nigga -- we do what we want to do." Visits to the Philadelphia locker room were the stuff of great theater, as Barkley continued to castigate the press and a city still divided by race.

"Just because you give Charles Barkley a lot of money, it doesn't mean I'm going to forget about the people in the ghettos and slums," he lectured. "Y'all don't want me talking about this stuff, but I'm going to voice my opinions. Me getting 20 rebounds ain't important. We've got people homeless on our streets and the media is crowding around my locker. It's ludicrous." He called Philly a "racist city" and told the press to "kiss my black ass -- even though your lips might stink." He vowed, "I'm a strong black man -- I don't have to be what you want me to be," echoing an Ali line from the '60s after he read Thomas Hauser's oral history of the boxing great. When I told him I was writing a magazine profile of Erving, he dismissed the legend: "Man, I ain't got no time to talk about no Uncle Tom."

By 1992, Barkley was the NBA's second-best player, behind Jordan, but he'd grown frustrated with Philadelphia's management for surrounding him with a rotating cast of mediocre players. Management, in turn, had tired of Barkley's outspokenness. He was traded to the Phoenix Suns, and the night before he went West, my phone rang. It was Charles, calling to thank me for leaving for him a copy of "The Autobiography of Malcolm X," about whom we'd been talking. He sounded pensive, even glum. "I'm just driving around, thinking," he said. "This has been home for eight years. I don't know what to expect somewhere else." His voice, barely a whisper, made him sound vulnerable. Oh yeah, I remember thinking, he's still in his 20s.

It was further proof that, for all his loudmouth faults, Barkley often exhibited a greater potential for growth than any other athlete on the public scene. He was always answering questions, questioning answers and -- often -- lapsing into introspection.

Such iconoclasm was on display in 1988, when he told his mother he was considering voting for George Bush. "But, Charles, Bush is only for the rich," she said. "Mom, I am the rich," he replied. Or, three years later, when his friend Magic Johnson tested HIV positive and other players, like Malone, were calling for uniform testing in the NBA. Barkley simply stated: "I'm disappointed in myself that I haven't felt the same compassion for other people stricken with AIDS that I now feel for Magic."

In Phoenix, Barkley became a superstar. He was the league's MVP and took his Suns to the NBA Finals in 1993, where they lost to Jordan's Chicago Bulls in six hotly contested games -- arguably the toughest challenge to Jordan's dominance in six championship seasons. On court, basketball fans finally saw that Barkley was the consummate team player; his five assists per game, often on eye-popping behind-the-back passes while double-teamed, gave lie to the conventional wisdom that permeated his last years in Philadelphia: that he was a talented player who couldn't make his teammates better.

Off the court, Barkley continued to evolve. He entered a Republican makeover phase. His worldview began to mature; he became more focused on class and less virulent on race. He also grew close to Rush Limbaugh and Dan Quayle (a frequent golf partner), dined with Clarence Thomas and endorsed Steve Forbes in the presidential primary. Though exit polls showed that his imprimatur sealed Forbes' primary win in Arizona in 1996, Barkley didn't necessarily sign on to any particular ideology.

He's become impossible to pigeonhole. He regularly lambastes liberalism, to the proud applause of Limbaugh and Quayle; two years ago, he told me, "Welfare gave the black man an inferiority complex. They gave us some fish instead of teaching us how to fish." In the next breath, though, he's liable to skewer 1994's Republican revolution as "mean-spirited" and denounce Pat Buchanan as a "neo-Nazi." A junkie of CNN's political gabfest "Crossfire," Barkley became convinced, after reading Jonathan Kozol's "Savage Inequalities," that the way we fund public schools -- through local property taxes -- is designed to produce good schools in good neighborhoods and run-down schools in run-down areas. "My daughter goes to a private school because I can afford it," he once told me, giving voice to his natural inclination toward populism. "But shouldn't everyone have great education available to them?"

He may read about failing schools, but Barkley hasn't exactly become a nerdy policy wonk. Throughout his time on the public stage, he's reveled in his fame, as when he had a brief, much-publicized tryst with Madonna, prior to a reconciliation with his wife. Then, as now, he insisted on livin' large: "We ain't here for a long time, we here to have a good time," he often says.

Indeed, while Jordan became a reclusive prisoner to his iconic status, Barkley lived to be out among the masses, and his nightclub hopping led to more than one mano a mano face-off with loudmouth fans. "Let there be no conflict in America," Barkley said in 1997, after he tossed an obnoxious heckler through a plate-glass window in an Orlando, Fla., bar. "If you bother me, I whup yo' ass." His career has been dotted with such run-ins; they are the collateral damage of a personality that, as on the court, simply plows ahead, rarely stopping to consider each and every move.

Barkley never made it back to the Finals. His body had been badly beaten through so many years of being manhandled by bigger players, not to mention the ill effects of his legendary hard-drinking, late nights. When it got out that the Suns were fielding trade offers for him in 1996, he exploded: "The days of cotton picking are over," he told the Phoenix media. "They disrespected me by shopping me around like a piece of meat."

Traded to the Rockets, Barkley joined two other aging superstars, Hakeem Olajuwon and Clyde Drexler, in his quest for a championship. But Olajuwon and Drexler already had their championship rings and didn't seem as committed as Barkley, who cut down on his drinking, started lifting weights and even offered to come off the bench for the good of the team in the 1997-98 season. But he was a shadow of his former self. "I'm the artist formerly known as Barkley now," he told me in 1998. "Once in a while, I get flashbacks."

Indeed, his own self-analysis was typically blunt. "I'm still a good player, not a great player," he said. "I can score 15 points and get 10 rebounds." Yet the ceaseless questions about never having won a title carried the implication that he'll be remembered as less of a winner than his more hallowed contemporaries. He began to think of himself in relation to those who have won rings. "I've never played with a great player in his prime while I've been in my prime," he said. "Michael has had Scottie [Pippen]. Bird had Kevin [McHale] and Robert Parish. And Magic, shit, Magic had everybody. When I came into the league, Doc and Moses were winding down. And Hakeem and Clyde, same thing."

Toward the end, as a merely good player, it became easy to forget what the younger Barkley once was. More than a great player, he was, like Jordan, a wonder on the court: You'd watch and not quite believe it. He was a jumping jack who was too quick for other power forwards, too strong for small forwards and too visionary a passer for the double-team. And it was all done with an in-the-moment passion missing from today's scowling, dour-faced jocks.

Off the court, ironically, Barkley became the league's elder statesman these last few years, a respected spokesman for tradition and the status quo. At times, he'd sound like Paul Lynde from "Bye Bye Birdie," wringing his hands over "these kids today." When it was written that the cornrowed, tattooed Allen Iverson travels with a "posse" -- friends from back home -- Barkley admonished him: "Your teammates should be your posse." When I offered that guys like Iverson see the league's crackdown on droopy uniform shorts as a sign of hostility toward black culture, he demurred: "They're wrong," he said. "The shorts now are getting to the point where they don't even look like shorts. I think the NBA has to be concerned with a lot of black guys getting arrested, me included, doing drugs, wearing shorts down to their ankles. That's not hostility to black culture. That's just reality."

Still, though the volume came down a bit, Barkley continued throughout his final years as a player to challenge the predilections and prejudices of the men who present him to the world. He calls the journalistic pack "flies," because they're always buzzing around, annoying. One day, in front of his locker, I witnessed pure Barkley. Before the throng could lob its first question at him, Barkley singled out a Houston television reporter. "Would you suck a cock for a million dollars?" he asked. A roomful of men all instantly looked at their shoes.

"No," came the cracked-voice reply.

"A billion?" Barkley challenged.

"No," said the reporter, stronger now.

"Well, how much then?"

"I wouldn't do it for anything!"

Barkley grinned widely. "Well, if you'd do it for free, come on over here then," he said, while nervous laughter filled the air around him. "Tell y'all what, I would. If I was poor, I'd suck a cock for a million dollars."

He paused and looked at his audience. "And all you muthafuckas would do the same, you just scared to admit it," he said. "Like, remember when that movie 'Indecent Proposal' came out? Oprah had on three couples who said they wouldn't let their husband or wife sleep with someone for a million dollars. Couldn't help but notice that they all had money already."

After an awkward moment of silence, the flies started buzzing again, shouting basketball questions over one another's still trembling voices. I remember standing there, feeling lucky as hell to have seen this guy in action. After all, anyone who appears so utterly joyous exercising free speech, anyone so OK with his life as a very public work-in-progress and anyone in the insular, often homophobic world of jockdom who points out class distinctions by challenging the media to suck cock for money, well, that's a role model worthy of emulation.

Shares