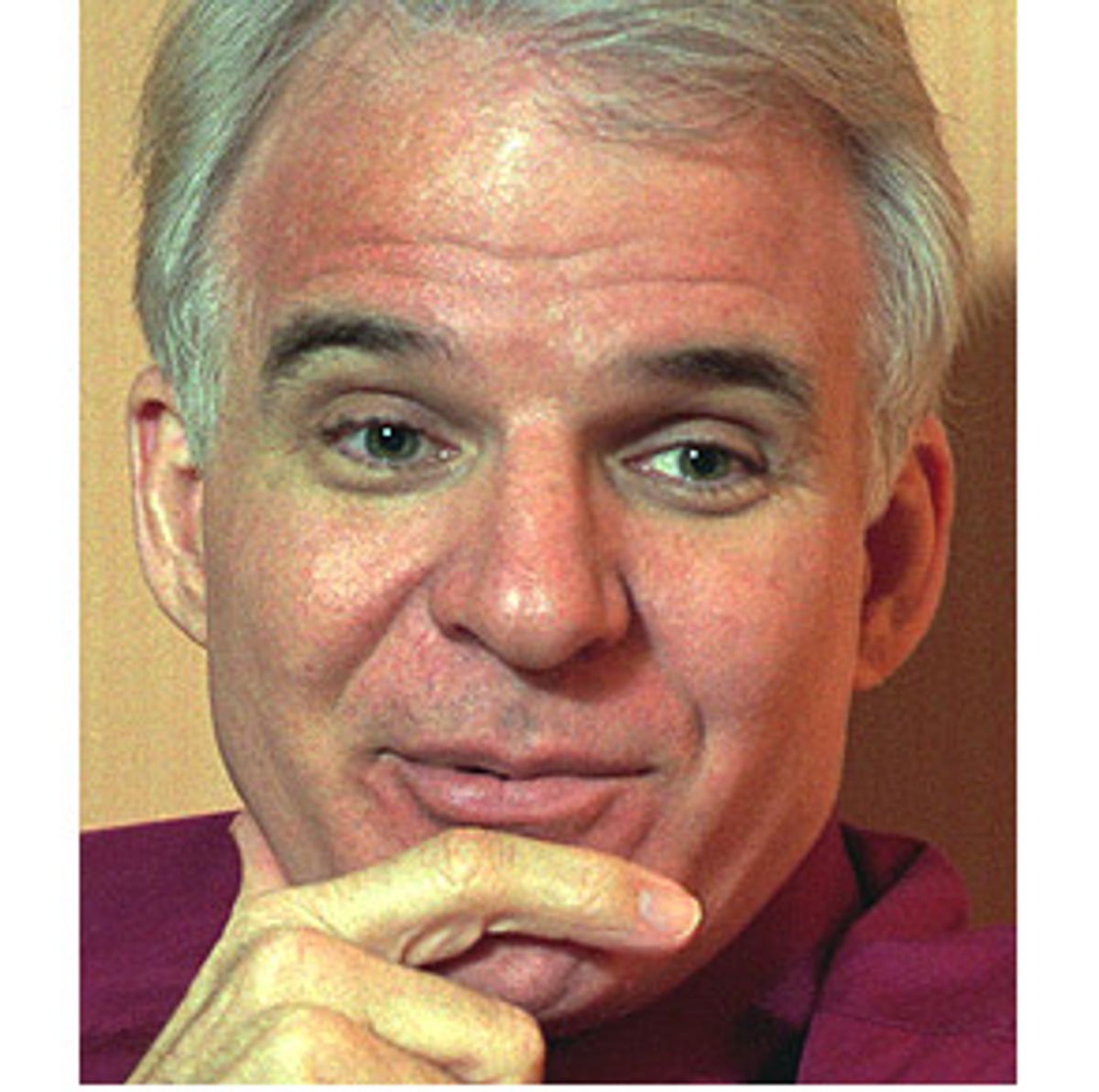

When I was in junior high, circa 1977, Steve Martin was God. All of my geeky buddies had a copy of Martin's LP "Let's Get Small." Later, we added "A Wild and Crazy Guy" and his book "Cruel Shoes" to our growing Martin shrines. We set his skits to memory as dutifully as we had the lyrics to Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" or Blue Öyster Cult's "Don't Fear the Reaper." The really obsessed kids wore plastic arrows through their heads on the bus to school while mimicking the various catchphrases Martin had drummed into the collective consciousness of Carter-era America, such as "We're havin' some fun," "I've got happy feet" and the ever-popular "Well, excuuuuuse me!" We all wanted to be Steve Martin.

It was that gilded era of comedy known as the '70s -- a decade when the "National Lampoon Comedy Hour" graced the FM airwaves, the Not Ready for Prime Time Players of "Saturday Night Live" smoked pot on TV and Martin, a 32-year-old, banjo-playing, balloon-animal-twisting, prematurely gray comic performed before hysterical, rock concert-like crowds of 20,000 or more.

Martin's early LPs and stage performances were genuinely hilarious, but even the funniest bits, like the one in which he describes giving his cat a bath (with his tongue) or in which he has an entire audience repeat the "Non-Conformist Oath" ("I promise to be unique. I promise not to repeat things other people say!"), do not fully explain the late-'70s Martin mania. He also had the good fortune to be in step with his times. Following Vietnam, Watergate and the racial and civil unrest of the '60s and early '70s, folks needed a break from all the drama and heartache, and Martin's goofy, apolitical humor was a perfect match.

A lot of his comedy relied on irony and allowing his fans in on the fact that he was making fun of show business. He was like a magician revealing how certain standard, almost clichéd tricks are done, while parodying the idea that there is really any illusion involved. He just assumed you knew there was really no rabbit in the hat. When he put on that "Mr. Showbiz" demeanor along with the white suit and the bunny ears, it was as if he was saying, "See, I'm supposed to be funny." Martin's shtick was to take the oldest bits in the book and blow them up to outrageous proportions. You couldn't help laughing.

"Martin was playing with the stand-up format itself," writes Phil Berger in "The Last Laugh: The World of Stand-up Comics." "He was lampooning the postures comics take to get in good with the crowd -- the stroking they do to loosen up an audience. 'How much did it cost to get in?' Martin would ask. 'Eight-fifty? Ha ha ha. You idiots.'"

There were some "blue" bits in Martin's material, but not as many as in the work of, say, Rodney Dangerfield or a later comic like Sam Kinison. This also helps to explain Martin's wide appeal. Not only did all of my pencil-necked amigos in junior high dig him, so did high school and college students. And my parents adored him. As for Grandma, she thought he was cute, though she didn't get what all the fuss was about.

Now that same guy is doing voice-overs for Merrill Lynch commercials, a transformation that really struck me when I went to my local bookstore to get a copy of Martin's recent novella, the New York Times bestseller "Shopgirl." The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had recently announced that Martin will be the host of this year's Oscars, triumphing over gross-out-meister Jim Carrey. ("If you can't beat 'em, join 'em," quipped the as yet Oscar-less Martin in a press release.)

A young woman in her 20s rang up my purchase. "That's a great book," she offered. "Did you know he used to be on 'Saturday Night Live'?" I then realized how complete Martin's metamorphosis has been. He's gone from madcap comic deity, earning yuks by juggling cats and making fun of the French ("They have a different word for everything!") to distinguished elder statesman of humor, writing droll little shorts for the New Yorker.

As the '70s came to an end, Martin left stand-up for films. He knew instinctively that he was draining himself of all his psychic resources and had to get out. When Rolling Stone interviewed him in 1999, he compared performing before tens of thousands of screaming fans in the '70s to "conducting an orchestra" with "visual cues, verbal cues." Though he enjoyed a creative high during that period, he does nothing to hide his current distaste for that life. "I can't think of anything worse than being a stand-up comedian," he confessed. "Traveling around constantly, having people be drunk and talk during the show."

"The Jerk" was his farewell to all that. He wasn't giving up on comedy, just stand-up. It was all an act anyway, and it had taken him as far as it could. He didn't want to end up like Jerry Lewis, a prisoner to that Frankenstein monster of personified idiocy.

Directed by Carl Reiner and coming at the zenith of Martin's stand-up success in 1979, "The Jerk" transformed a $4.5 million investment into $100 million gross and made Martin a bona fide movie star. The move to film was a shrewd, calculated gamble that paid off handsomely. Martin had taken the next logical step at the right moment in his career, and could now leave the road behind forever.

"Stand-up comedy was just an accident," he told Rolling Stone in 1982. "I was figuring out a way to get onstage. I made up a magic act and that led to nightclubs. As I got into movies, I was reminded that this is really why I got into show business. With movies you've constantly got new material, new challenges."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Waco, Texas, is famous for three things: Dr Pepper, David Koresh and Steve Martin. Martin was born in Waco on Aug. 14, 1945, and he lived there until his family up and moved when he was 5, first to Inglewood, Calif., and, later, south to Garden Grove, a right-wing burg nestled deep in Orange County, that nexus of arch-conservatism known for nurturing a particularly nasty breed of Republicans. Martin's dad was a prosperous real-estate broker who never quite understood his son's ambition to be an entertainer.

As a teenager, Martin snagged a job hawking guidebooks at Disneyland in nearby Anaheim, and he found that he could sell more with a bit of shuck 'n' jive. A little banjo, a few jokes, some balloon animals and voilà, he had an act. At 18, he graduated to a gig as an entertainer at Knott's Berry Farm. There he honed the skills he'd later use to entertain millions.

In the '60s, he studied philosophy at Long Beach State University, the same school Steven Spielberg and the Carpenters attended. "I was either going to become a professor of philosophy or a comedian," he told Newsweek in 1977. "Then I realized the only logical thing was comedy because you don't have to justify it." A girlfriend helped him land a job writing for "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour," and he soon dropped out of college to write for TV full time. In 1969 he shared an Emmy in outstanding writing achievement for his work on "The Smothers Brothers."

Martin pursued stand-up while writing for various outlets. By 1975 he was packing them in at San Francisco's Boarding House club, among other places. Just then, a new TV show called "Saturday Night Live" was keeping everyone at home on Saturday evenings, and Martin soon began a string of popular appearances on that show and on Johnny Carson's "Tonight Show." Martin became an unstoppable force of comedy, a silver-haired zeitgeist wrapped in a double-breasted white suit.

He was comic gold. People laughed at every gesture, every utterance, no matter how mundane. In one skit from "SNL," he had the crowd in tears just from dancing around by himself onstage to some '40s big-band tune. And when necessary, he could always brandish his secret weapon -- the banjo. Play a little "Foggy Mountain Breakdown," blurt out a few quips and the crowd was his.

The awards piled up. "Let's Get Small" won a Grammy in 1977 for best comedy album. In 1978, he earned an Academy Award nomination for his short film "The Absent-Minded Waiter." He garnered another Grammy in 1979 for "A Wild and Crazy Guy," his album with the hit single "King Tut." Both LPs eventually went platinum.

There were more comedy records, more awards and nominations, but "The Jerk" cemented his status as a superstar. He could have easily dived into another comedic film right away, but Martin bucked the advice of his manager by pursuing the lead in Herbert Ross' 1981 film version of Dennis Potter's bleak BBC musical "Pennies From Heaven." The role of Arthur Parker, an ill-fated sheet music salesman in the '30s, had already been turned down by numerous A-list stars because it required so much work. Martin, however, relished the challenge of emulating the likes of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. Under Ross' intense tutelage, Martin became an expert hoofer, able to hold his own with Gregory Hines when they danced together on a comedy special after "Pennies" was released.

In "Pennies," teamed again with his "Jerk" costar and then girlfriend Bernadette Peters, Martin and she lip-sync and sway to Depression-era tunes, such as "Let's Face the Music and Dance" and "Love Is Good for Anything That Ails You." Both stars shine like screen giants of yesteryear. The result is the one true work of art Martin has helped create -- the one film with the depth and originality to be pegged as a masterpiece. The critics were divided on it, and audiences, perhaps expecting the Martin of "The Jerk," generally didn't get it. In hindsight, with Lars von Trier's black musical "Dancer in the Dark" under our belts, "Pennies From Heaven" seems way ahead of its time.

Martin was disappointed that "Pennies" was a commercial flop. "I loved that movie so much. The most heartfelt thing I've ever done was 'Pennies From Heaven,'" he told Penthouse in 1984. Still, Martin plowed ahead to make innovative flicks like the 1982 noir pastiche "Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid" and "The Man With Two Brains" (1983), wherein Martin's character attempts to implant the disembodied gray matter of a sweet, intelligent young woman into the skull of the brazen and bitchy Kathleen Turner.

In 1984, Martin received high marks from critics for another mind-body switcheroo flick, "All of Me," costarring Lily Tomlin. On the set, Martin met and became enamored of British actress Victoria Tennant. The pair wed at Rome's City Hall in 1986. Considering Martin's success, money and fame, he could pretty well have had his pick of Hollywood after he and Peters parted ways. But Martin longed for substance over eye candy -- and that's what he saw in Tennant. No doubt her brains, refined breeding and British accent appealed to him.

Martin revealed as much in his 1991 romantic comedy "L.A. Story," his love letter to Los Angeles and Tennant after the manner of Woody Allen's Gotham-based "Annie Hall." Martin plays a parody of himself, a wacky TV meteorologist named Harris Telemacher, dying of cerebral thirst in the arid intellectual climate of Los Angeles. Along comes Tennant as limey Sara McDowel, who sweeps him off his roller skates. The parallels to Martin's own life are too close to be coincidence.

Tennant divorced Martin in 1994, and since then he's been paired with more than one Hollywood beauty, including Anne Heche and Helena Bonham Carter, but he hasn't remarried.

Martin has remained enormously prolific, doing almost a film a year since 1981, and sometimes more. Of these, a good many have been tepid Middle American fare such as "Mixed Nuts" (1994), "Parenthood" (1989) and "Father of the Bride" (1991). But to Martin's credit, there have been some gems, like his cameo in Frank Oz's "Little Shop of Horrors" (1986) or his leads in "Roxanne" (1987), "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" (1988), "Planes, Trains & Automobiles" (1987) and "Bowfinger" (1999).

Nor has Martin been wary of redefining himself and taking risks: for example, his venture into playwriting with the 1993 stage comedy "Picasso at the Lapin Agile," which New York magazine called a "very funny riff on the birth of the modern century." Other reviews were less kind to the production, which featured Einstein and Picasso meeting for a drink in 1904 at a Parisian cocktail bar. The New York Times said Martin's play "captures the inevitable way art and celebrity have merged," but chastened its shallowness. Still, "Picasso" had successful runs in Chicago, New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, and it enhanced Martin's image as a thoughtful manipulator of ideas.

He is at heart an intellectual and an aesthete. He's a longtime trustee of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with a gallery named after him. And he possesses a highly regarded art collection made up predominantly of 20th century American painters such as Edward Hopper, Willem de Kooning and Richard Diebenkorn.

In addition, Martin has penned a number of short essays for the New Yorker and other publications. In 1998, he collected them all in a slim volume titled "Pure Drivel." The anorexic tome had critics gushing with superlatives. Now there's "Shopgirl," which novelist John Lanchester, writing for the New York Times Book Review, called an "elegant, bleak, desolatingly sad first novella."

The plot deals with the oft-visited theme of May-December romances, and one suspects that Martin is drawing on life experience here. The affair in question is between a 28-year-old clerk at Neiman Marcus in Beverly Hills and a 50-ish Seattle computer magnate. There's nothing terribly original about the people or the story, but Martin crafts a convincing portrait of loneliness in his protagonist Mirabelle. Even Martin, now a wry, wise 55, seems to realize that his literary debut may never have occurred were it not for his name.

"There's nothing more embarrassing then being a celebrity novelist. You just don't want to hear that an actor has written a novel. It really smells," Martin admitted to the New York Times last October. Well, at least he's not coughing up "Steve Martin's Wild and Crazy Pasta Recipes," which probably would spend an equal amount of time on the bestseller list.

With Martin's Academy Awards gig this month and a dark comedy titled "Novocaine" due out later this year, featuring Martin as a dentist opposite Helena Bonham Carter, we can look forward to seeing more of him -- more of the mature, urbane version, that is. As long as he continues to take risks, at least some of what he produces will be exceptional. No one's perfect.

"I'll never run out of stuff," he told Penthouse in 1984. "Because there'll always be something to twist. As it's developed, my whole comedy personality is bent. It's tilted towards irony, like the bore at the party."

Shares