Anyone seeking the distilled essence of Tom Waits can find it in a song that he didn't even write. Waits is an inimitable song stylist (take a look at efforts by the Eagles and Rod Stewart to cover his songs if you don't believe me), but it is his cover of a show tune that may help explain him best.

Growing up in Southern California, I spent countless hours in my parents' car. Unfortunately my father owned all of four cassettes, which were in heavy rotation for the better part of 16 years. And even worse, one of those cassettes was a tape of show tunes sung by Barbra Streisand. As a captive in the back seat, there was little I could do.

When Babs delivers her melodramatic rendition of "Somewhere" from "West Side Story," it is utterly uncompelling. When she sings the song's opening line, "There's a place for us/Somewhere a place for us," it's impossible to feel anything real. We all know that place she sings of is among brie platters and chardonnay on the terrace of a $27 million Malibu estate. Tough life.

But when Waits delivers the same line to open his 1978 album "Blue Valentine," the song is transformed. Through Waits' raspy wail, the song moves closer to its own spirit -- an ode to the freak, a tragic vision of a nonexistent Utopia where all of Waits' characters can roam free.

And imagine if they all were there. The one-eyed dwarf captain shooting dice along the wharf, the prostitute in a Minnesota jail who fabricates stories about a trombone-playing sugar daddy, Big Mambo kicking his old gray hound around the neighborhood; the list goes on and on. Certainly this bunch would not know what to do with the "peace and quiet and open air" that await in some distant somewhere. These are people trapped in what a patient Christian might call the tunnel toward salvation.

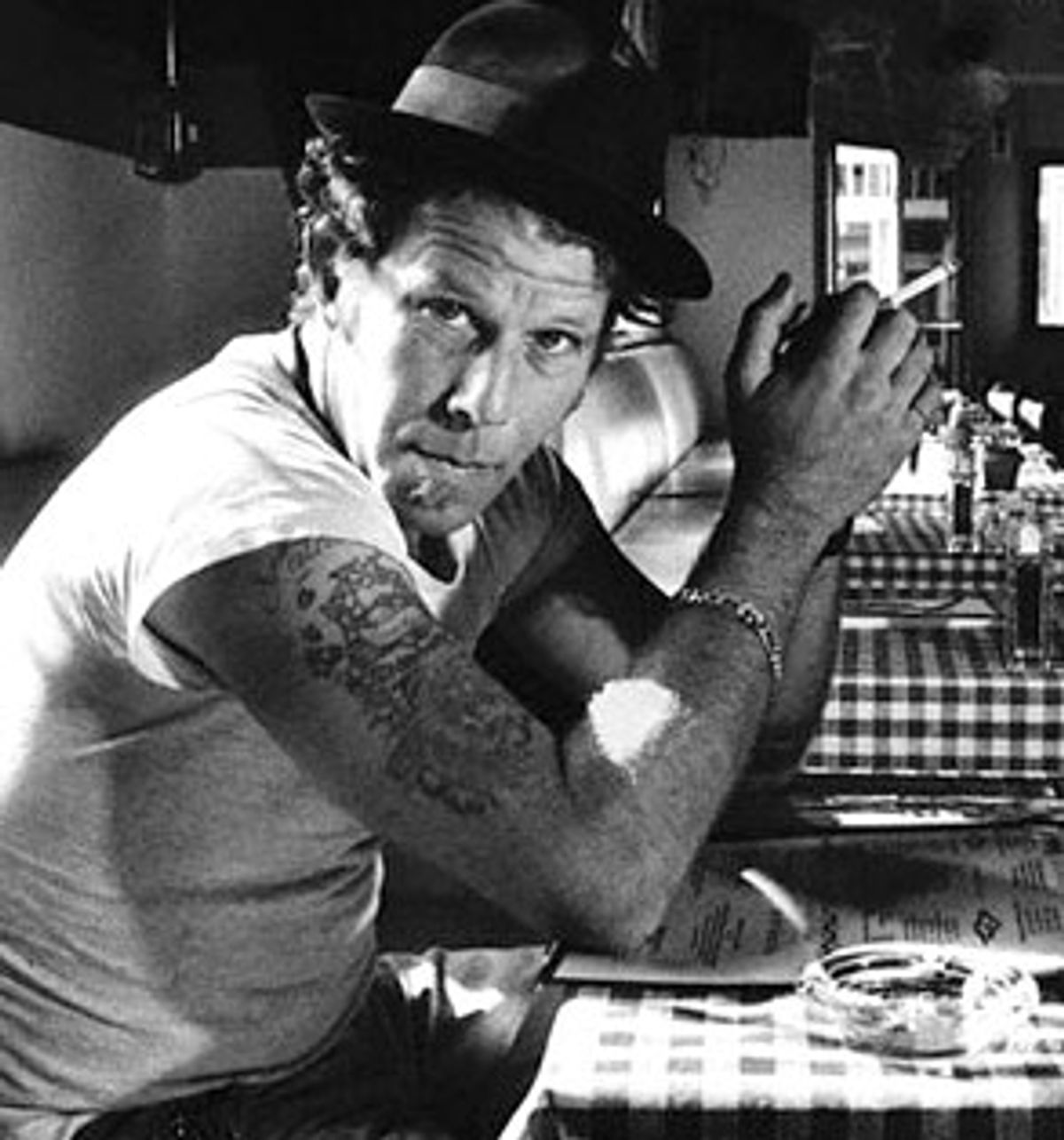

For the rest of us, this is just as well. To live in Waits' world is to celebrate loneliness and desperation. Sure, he can sing the ballad of the last man at the bar, but Waits is more than just a piano bar crooner. He's also the Coney Island carnival barker shining a soft blue spotlight in the back alleys of New Orleans. And he does it all with such style, singing about the same characters Charles Bukowski wrote about, in a throaty growl strangely derivative of Louis Armstrong.

Waits has cited as influences everyone from Hound Dog Taylor to his Uncle Vernon, from Prince to Blue Oyster Cult. He once said he enjoyed listening to BOC "about as much as listening to trains in a tunnel." But in a 1978 interview with Creem magazine, Waits explained that, coming from him, that was an endorsement. "I like them. Of course, I also like boogers and snot and vomit on my clothes."

Not your typical rock-star aesthetic, to be sure. But Waits has also had an extensive and eclectic film career, beginning with Sylvester Stallone's 1978 "Paradise Alley." In the 23 years since, he's had memorable roles in movies such as Jim Jarmusch's "Down by Law" as well as in some more forgettable ones, like 1999's "Mystery Men."

But through it all, he has maintained his place as the ultimate hobo boho, a Jack-in-the-box cum storyteller. He brings a certain savvy to almost everything he touches -- whether it's sticking a live fish down his pants while fishing with John Lurie on the Independent Film Channel, or playing Zack the DJ convict in "Down by Law," or prancing around drunk opposite Lily Tomlin in Robert Altman's "Short Cuts." Waits is the King Midas of cool.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Tom Waits was born in the back seat of a taxicab in Pomona, Calif., on Pearl Harbor Day, 1949. He once told Rolling Stone he began to come into his own musically when he "started writing down people's conversations as they sat around the bar. When I put them together I found some music hiding in there."

His first albums were your basic white-boy blues efforts. In fact, when two albums of his early recordings were rereleased in the early 1990s, I was half-convinced they were some sort of elaborate prank.

"The Early Years" Vols. 1 and 2 are striking in the context of Waits' body of work. To hear them is to listen to a singer who has not yet found his voice. Songs like "Pancho's Lament" and "Goin' Down Slow" sound like they could be Randy Newman tunes, for chrissakes. But listening to these songs confirms something else -- that Waits is the ultimate character actor. Even in these fledgling efforts there are signs of where he wanted to go. He just hadn't yet developed the means to get there.

But somewhere along the way his voice dropped an octave and he became Tom Waits. You can chalk it up to bourbon and cigarettes, but that seems too easy. Certainly, this evolution was complete by the time "Blue Valentine" was released. By then, Waits had become the hissing cobra of spilled Chablis along the midway, the guardian of Latino thugs getting cooled while stealing diamond rings, the chronicler of the rain washing memories from the sidewalks.

Waits says he began searching for that voice at an early age. "I learned that Uncle Vernon had had a throat operation as a kid and the doctors had left behind a small pair of scissors and gauze when they closed him up," he said in an interview with Creem. "Years later at Christmas dinner, Uncle Vernon started to choke while trying to dislodge an errant string bean, and he coughed up the gauze and the scissors. That's how Uncle Vernon got his voice, and that's how I got mine -- from trying to sound just like him."

This all culminated in 1983's "Swordfishtrombones," which still stands as Waits' masterwork. On the album, Waits ditched the simple guitar, drums and piano and added bagpipes, trombones, calliopes, strings, hurdy-gurdies, a little sizzle in the high hat, clanging lead pipes, an accordion -- anything and everything.

Waits said the transformation was liberating. "Anybody who plays the piano would thrill at seeing and hearing one thrown off a 12-story building, watching it hit the sidewalk and being there to hear that thump," Waits told Playboy magazine. "It's like school. You want to watch it burn."

Freed from the confines of the standard jazz trio, Waits continued to experiment. He found music in "dragging a chair across the floor or hitting the side of a locker real hard with a two-by-four, a freedom bell, a brake drum with a major imperfection, a police bullhorn."

He also learned the art of evocative storytelling. Never in his later years would he make the mistake of overstating his case. His lyrics wouldn't have to tell you he was your "late night evening prostitute," as he sang on Vol. 1 of "The Early Years." It was in the music. Waits says this evolution began when he stopped romanticizing the life of a drunk.

"I tried to resolve a few things as far as this cocktail-lounge, maudlin, crying-in-your-beer image that I have," he said in a Rolling Stone interview. "There ain't nothin' funny about a drunk. You know, I was really starting to believe that there was something amusing and wonderfully American about a drunk. I ended up telling myself to cut that shit out."

Watching Waits on-screen, or listening to a record, is to watch or hear an elaborate act. But instead of being some kind of extravagant UFO fantasy, Waits' shtick seems to be about being himself, only more so. In that sense, he is the anti-glam rocker. Whereas David Bowie, for example, was always taking on new identities, creating and inhabiting new characters, Waits is a study in becoming who you already are. He's the guy who eats cold chow mein out of the box, revels in a new deck of cards with girls on the back. Bowie is from outer space. Tom Waits is from down in the hole.

"My thing is the best songs come out of the ground, just like a potato," he once said in a conversation with Roberto Benigni, which was published in Interview Magazine. "You plan and plan, and then you wait for the potato."

As far as life philosophy, Waits had this to say to a Time magazine reporter in 1978: "Life is picking up a girl with bad teeth, or getting to know one of those wild-eyed rummies down on Sixth Avenue."

And though his sensibilities may be dive-bar chic, Tom Waits isn't cool the way a pool hustler is cool. Waits is cool like saffron -- exotic and rare. He keeps himself in relative seclusion north of San Francisco, which only adds to the allure. Any time Waits plays a gig it becomes an event. He rarely tours anymore, though he did hit the road for a few dates in support of 1999's "Mule Variations." Those shows were his first since he emerged from a self-imposed exile in 1995 to play a single benefit concert at Oakland's Paramount Theater. The show was expensive -- $75 a ticket -- and sold out in less than an hour.

But Waits didn't miss a beat. When a woman sitting near the front yelled out, "Hey, Tom, where you been?" Waits had a reply at the ready, as if it were rehearsed.

"I been around. Where you been? You still living out by the airport?"

Pitch perfect.

Shares