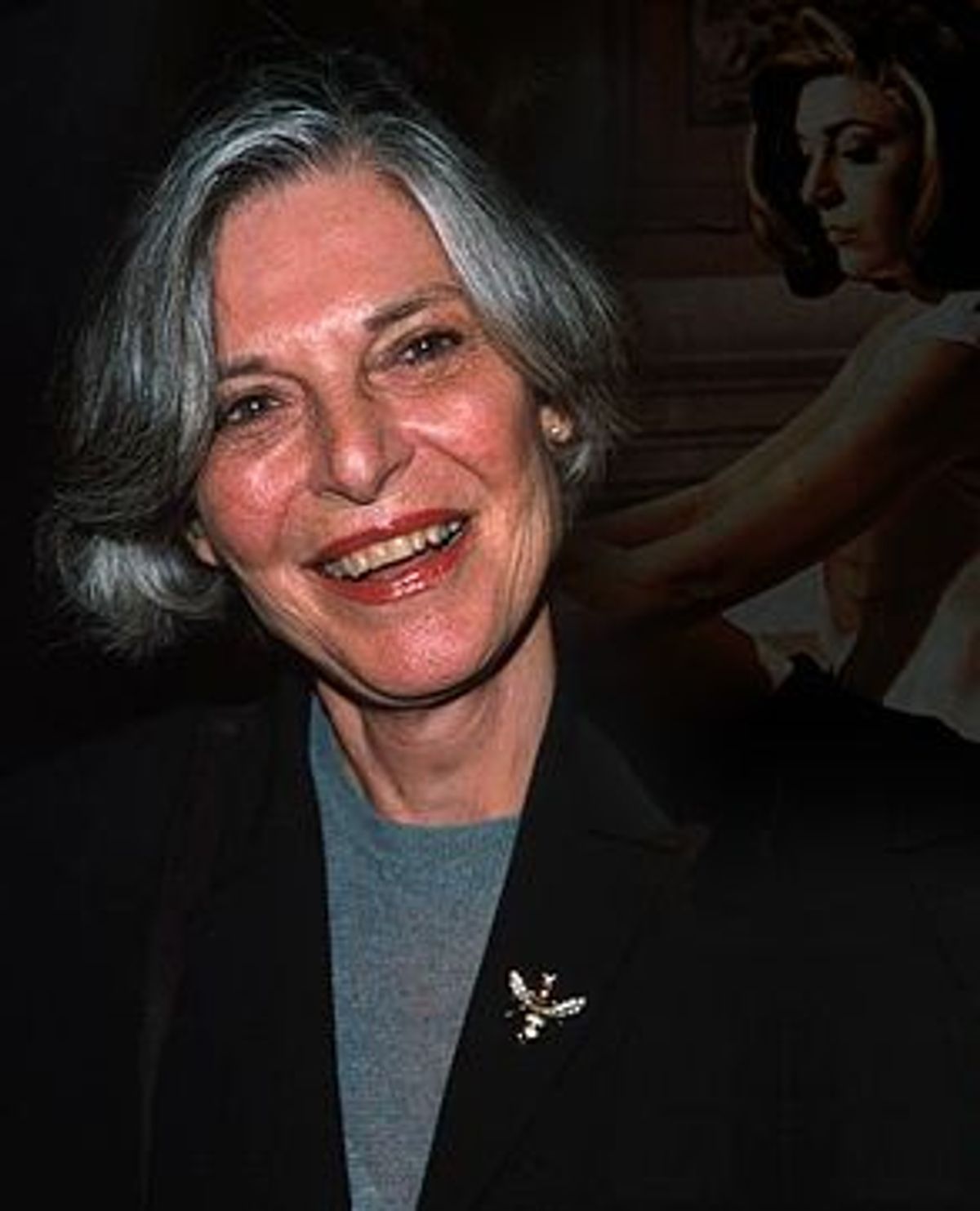

Although PBS's Charlie Rose is frequently so engaged in his interviews that he consumes more airtime than his guests do, it isn't often that he's reduced to an hour of schoolboy giggles, capped off by proclaiming, "I'm mad for you!" The woman who makes Charlie's knees shake? Anne Bancroft, the thinking man's fantasy, and the kind of woman thinking women want to be. Bancroft is on fire with ideas, brimming with passions, supremely confident and self-aware, without taking herself too seriously or pretending to have all the answers. She turned 70 on Sept. 17, and she still has a body that's ballerina graceful, eyes that reveal the truth (a poker player she is not) and a voice that seems to say, "I'm not gonna take any bullshit," even as "Why, thank you, Sweetheart" leaves her mouth.

In everything she does -- the roles she chooses and the ones she passes by, the image she maintains and the ones she rejects, the hours she works and the ones she spends fishing with her husband (how's that for an image?) -- Bancroft is uniquely herself.

She was born Anna Maria Italiano in the Bronx in 1931, a performer from the start, entertaining aunts, uncles and cousins at frequent family get-togethers; trolling for workmen on her neighborhood streets; and impressing her teachers and fellow students in grammar school. Bancroft's parents, always supportive of her passion for performing, paid the tuition for her schooling at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in Manhattan, which she attended after high school. It was near the end of her time at the AADA that she was seen rehearsing alone on the stage during her lunch hour ("I had no money for malteds and no dates. What the hell was there for me to do but stay onstage when the other kids were out?" she would later explain to Time) and was asked to audition for "Studio One," a popular dramatic television series. She did, and landed her first professional role, which was soon followed by other television performances.

Bancroft grabbed the attention of 20th Century Fox in 1951, when she read opposite another actor in a screen test for the studio. The actor who was being screen-tested didn't get anything out of the arrangement, but Bancroft was signed by Fox and headed out to Hollywood, where she would play mostly supporting parts -- in such roles as a lounge singer, a trapeze artist and a gangster's daughter -- in a string of low-budget pictures. She later told Time, "The studios wanted to give me the Monroe-type sex buildup. I wanted to develop my acting, not my body." And Hollywood publicity shots of Bancroft from that period reveal exactly that. She's a girl you wouldn't recognize -- polished, coiffed and made up to look like someone she hasn't been, on-screen or off, since. (And not because she hasn't played sexy roles, but because the studios didn't recognize then that there was more to her than her looks.) In her photo, there's a gaze of uncertainty we're not accustomed to seeing in Bancroft's eyes -- in her strapless dress and choker, she looks like a girl playing dress-up, trying to convince herself it's real.

The chance she was looking for to prove herself as a serious actress came along in the form of a Broadway play called "Two for the Seesaw." As Gittel Mosca, a Jewish, bohemian dancer from the Bronx, Bancroft starred opposite Henry Fonda and went on to win a Tony for her performance in 1958. She followed up "Seesaw" with the part of Annie Sullivan in "The Miracle Worker," for which she won her second Tony.

Although her work in "Two for the Seesaw" had been critically acclaimed, there were those who weren't yet convinced that Bancroft was doing much more than playing herself. Her portrayal of the half-blind, Irish-American Annie Sullivan immediately dispelled any of those doubts. Upon seeing the play, author Edwin O'Connor said, "This is the most astonishingly accurate Irish accent I've ever heard. It sounds as if she'd been born in Galway."

In addition to proving her mettle on Broadway, Bancroft reprised her role in the 1962 film version of "The Miracle Worker." Her extensive preparation -- a Bancroft trademark -- together with the time she spent inhabiting the character onstage (nearly a year and a half by the time shooting started in the summer of 1961) made for a triumphant return to film. Bancroft's Annie Sullivan approaches Helen Keller (Patty Duke) with an almost ferocious desire to break through, to show her that things have names and those names are strung together to express ideas, to help her see the connections between the physical world around her and the world she inhabits in her mind.

When Helen's older half-brother, James, tells Annie, "Maybe she'll teach you ... that there's such a thing as dullness of heart, acceptance and letting go. Sooner or later we all give up, don't we?" Bancroft replies, "Maybe you all do. It's my idea of the original sin," and you can't help but get the sense that Bancroft is saying those words for herself, as well as for the character.

"Most of Annie Sullivan is myself," Bancroft told Time while on Broadway. "It's my own blindness I draw on, my unawareness of myself." If she was drawing on herself in playing Sullivan, then the battle scene serves as proof of director Arthur Penn's thoughts about Bancroft at the end of filming. He told reporters, "You have to understand, you see, that Annie's a very gutsy girl. I swear I wouldn't hesitate to put her in at shortstop for the New York Yankees." The following spring, that gutsy performance brought Bancroft the Academy Award.

Within just a few years, she had made the giant leap from a B-movie starlet without many prospects in Hollywood to a Tony- and Oscar-winning actress whose face had graced the cover of Time. After "The Miracle Worker," Bancroft starred in the 1964 film "The Pumpkin Eater" (written by Harold Pinter and based on the Penelope Mortimer novel), for which she received her second Oscar nomination. In 1965, she played opposite Sidney Poitier in Sydney Pollock's "The Slender Thread." And in 1966, she replaced Patricia Neal (who had suffered a stroke) in "7 Women," which would be director John Ford's last feature film.

But the project for which Bancroft is best known is Mike Nichols' "The Graduate," released in 1967. Although she loved the script immediately, she was discouraged from taking the part of Mrs. Robinson by nearly everyone, because it was, they thought, beneath her. But the naysayers didn't succeed in convincing Bancroft that she shouldn't play Mrs. Robinson (as she told Charlie Rose, "Besides, there was nobody else who could play that part like I did"), and a legendary character was born.

It is at the graduation party thrown for Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) by his Beverly Hills socialite parents that the camera lights upon Mrs. Robinson for the first time. While the Braddocks' friends swarm around Ben, telling him, and each other, how "proud, proud, proud, proud, proud, proud, proud" they are of the track star, Mrs. Robinson sits alone, with a cigarette, watching like a leopard in wait. When Benjamin breaks, heading for his room, she goes in for the kill, but in a slow, methodical way -- staying one step ahead of him at each turn in their conversation, cutting him off before he can say no (and ignoring him when he does) and eventually luring him into her lair.

It would have been easy for Mrs. Robinson to come off as a one-dimensional seductress, leaving Benjamin with no alternative but to play the part of the victim -- a horny victim, but a victim nonetheless. Instead, Bancroft brings to her character a life not explicitly spelled out in the script -- and, in so doing, extends that multidimensionality to every other major character in the film.

In the end, the notorious Mrs. Robinson was, Bancroft told Rose, misunderstood: "She was not understood by herself, and she was also not understood by the society around her. I think she had dreams, and the dreams could not be fulfilled because of things that had happened. And so she spent a very conventional life, with this conventional man, in a conventional house. ... And meantime, all the dreams that she had had for herself, and the talent -- she probably was a gifted artist ... I thought that she was -- and none of that could happen anymore." In the film, Bancroft communicates this message, in its entirety, in the span of less than a minute. Mrs. Robinson and Benjamin are in bed, and Ben asks her what her college major was. With her back to him, she says one word -- "art" -- but a look of sadness and vulnerability washes over her face.

"I guess you kinda lost interest in it over the years then," Ben says.

"Kind of," she replies.

As is so often the case in "The Graduate," Bancroft communicates more in saying nothing at all than most actors could say with an entire monologue. That one scene, in which she goes on to laugh with Ben and then seconds later grabs him by the hair and forbids him to see her daughter, defines the character. With her eyes alone, Bancroft gives voice to the fear we all have: that we'll reach a certain point in our lives, look around and realize that all the things we said we'd do and become will never come to be -- and that we're ordinary because of it.

In the 1977 film "The Turning Point," which brought Bancroft her fourth Oscar nomination (out of five to date), she plays the anything-but-ordinary Emma Jacklin, an aging ballerina who has passed her prime and is forced to comprehend the incomprehensible: that she is no longer the star, that there are other, younger dancers who can and will replace her. While Emma has spent the past 20 years putting her career above everything else, her good friend Deedee Rogers (Shirley MacLaine), once also a dancer, has left the company, married and had a family.

Bancroft was given the choice between the two roles. While in the running for the Oscar (Diane Keaton would win that year for "Annie Hall"), she explained to People magazine her decision to play Emma: "I identified with both women. But Emma had a stronger message for the women I want to speak to now -- women who work. I wanted to tell them that choosing to work doesn't make them oddballs and isn't antisocial." Emma is, on the surface, the antithesis of Mrs. Robinson -- a woman who has pursued her passion to the exclusion of any semblance of a conventional life. When Deedee asks her what her life is like, what it's like to be Emma Jacklin, she responds, "I dance. I take class, I rehearse, I perform. I go home to my hotel. Some cities are better than others. So are some nights." And you can't help but wonder if, in the end, Emma isn't every bit as alone as Mrs. Robinson is, despite the difference of her decision.

Bancroft herself has managed to have both a strong career and a fulfilling personal life. Married to Mel Brooks since 1964, she chose to stay home with their son as he was growing up, instead of building her career with the same intensity she had in the past. Of course, intensity is relative. She continued to work, although less frequently, throughout the '70s and '80s -- writing, directing and costarring in the film "Fatso" in 1980; playing opposite Brooks in his 1983 musical comedy "To Be or Not to Be" (the opening song-and-dance routine where Brooks and Bancroft sing "Sweet Georgia Brown" in Polish is itself worth a trip to the video store); and starring opposite Jane Fonda and Meg Tilly as the irascible Mother Miriam Ruth in 1985's "Agnes of God" (yet another Oscar-nominated performance for Bancroft).

In the past decade, she has become the actress people go to when they want a woman over 60 who's still got it, shining in such films as "Home for the Holidays" (1995), "How to Make an American Quilt" (1995), "G.I. Jane" (1997), "Great Expectations" (1998), "Up at the Villa" (2000) and "Keeping the Faith" (2000).

One of Bancroft's best films, perhaps, is a quiet little sleeper called "84 Charing Cross Road" (1986), based on the memoir by writer Helene Hanff. Playing Hanff, Bancroft is joined by Anthony Hopkins, as London bookseller Frank Doel; Judi Dench, as Frank's wife; and Mercedes Ruehl, as Helene's good friend. Light on plot and heavy with character, "84 Charing Cross" traces the 20-year correspondence between a brash, Jewish, New York writer and a quiet, reserved, British bookseller. Their friendship begins in the fall of 1949, when Hanff writes to the firm for which Doel works, requesting a particular used book she's been unable to track down in New York, and it lasts until Doel's death in December 1968. Because Hanff's plans for a trip to London never work out while Doel is alive, the entire friendship is based on letters -- fitting for a story about two lovers of the written word.

Despite the excellent supporting cast, most of what we see is Hanff on her own -- hammering her letters into her typewriter; shopping at the corner market; buying stamps at the post office and pounding them onto an envelope with her fist; wandering through Central Park; babysitting the infant daughter of a couple she knows (and reading John Henry Newman's "The Idea of a University" to her); standing in a crowd in front of a store window, watching the Brooklyn Dodgers play the Yankees in the Series. In the hands of anyone else, this could put even the most ardent book lover to sleep. But Bancroft brings to the film a depth and substance that enriches the letters themselves. The expressions on her face, the look in her eyes, help us read between the lines, into the story of Hanff's life that isn't told in the letters. When she writes to Doel, "You know, Frankie, you're the only soul alive who understands me," Bancroft is speaking, in a way, for many of the characters she's played over her 50-year career -- people who aren't understood, who are just a bit off-center.

Sometimes described by critics as giving performances that are over the top, in "84 Charing Cross" Bancroft's bold eccentricity and near-neurosis -- masking a certain gravity and introspection just under the surface -- are exactly what's called for. She's the perfect foil to Hopkins' stiff-upper-lip, God-save-the-Queen Brit. More than most of her recent performances (where she's played smaller roles in bigger films), her work in "84 Charing Cross" underscores the qualities that set Bancroft apart: a level of comfort with who she is and what she's about, and to hell with the rest of the world. As she told The New York Times while starring on Broadway in "Two for the Seesaw," at the age of 26, "I was at a point where I was ready to say I am what I am because of what I am and if you like me I'm grateful, and if you don't, what am I going to do about it?"

Shares