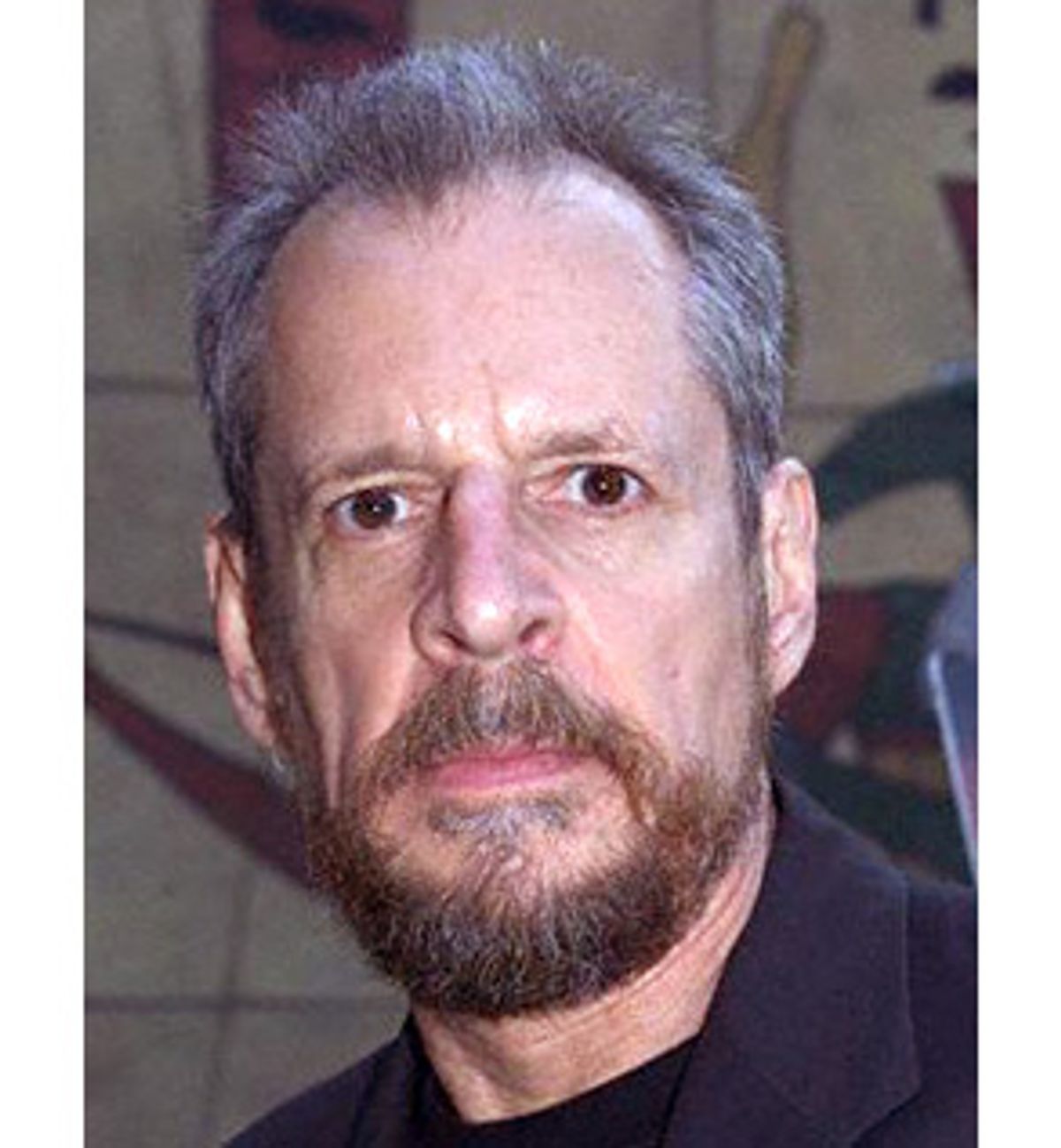

With a mug like Sterling Hayden's and a voice like an electric can opener, Larry Clark, 58, director of the new film "Bully," seems the unlikeliest of Pied Pipers. But ever since he started documenting -- some would say inventing -- the youth culture American parents would rather not know about, notably in 1995's "Kids," and long before that in seminal photographic books like "Tulsa" (1971) and "Teenage Lust" (1983), adolescents have followed and Clark has let his cameras catch them in flagrante delicto.

Shooting up, playing with guns and sex: This is what the teens in Clark's low-life American almanacs were shown doing -- all of it long before the likes of Nan Goldin and Gus Van Sant exploited such grimy gutter pearls for art's sake. But Clark was not off to the side with a camera. He was living the life. After "Tulsa," the National Endowment for the Arts awarded him a grant toward his next project, the even more explicit "Teenage Lust," but that had to wait while Clark did a stretch in Oklahoma's McAlester Penitentiary for a 1976 parole violation.

His troubled life and the fractured lives of his friends provided his first material, and he's been working the same disturbing vein for decades now, though he's moved from art books to cineplex fare. In "Teenage Lust" Clark reproduced a typewritten passage (all lowercase), signed "1974 Larry Clark," in which he recalls,

i always wished i had a camera when i was a boy. fucking in the backseat. gangbangs with the pretty girl all the other girls in the neighborhood hated. the fat girl next door who gave me blowjobs after school and i treated her mean and told all my pals. we kept count up to about three hundred the times we fucked her in the eighth grade. i got the crabs from babs. albert who said "no i'm first, she's my sister."

At the back of "Teenage Lust," in a 24-page stream-of-consciousness biography, Clark describes getting in a fight at a card game after he'd shot speed ("Do you like to fight?" his attackers ask him. "I don't mind," he responds) and then being handed a .22 Ruger pistol by his girlfriend:

So she gave me the pistol. I held it on them, and then I pistol whipped the main guy. I pistol whipped him across the house and he fell into the bathroom and fell on the shitter. And I shot him. In the arm. I just went ... I could have just as well gone through his head. So the other guys split.

Clark's struggles with heroin addiction, gunplay, sex and the dark side seem ever present. In a recent interview with the art journal Coagula, he asked: "Everyone gets their first blowjob, why can't you photograph that?" He finds beauty, or at least fascination, in the illicit and even the depraved. Perhaps film was a natural and safer progression for one with such a ravenous gaze.

Following "Kids," a brutal, elegiac tale of skateboards, sex and substance abuse, Clark could do no wrong in the eyes of the teens and art-house types who embraced him. But many others simply found his lurid visions of teenage intercourse, spliff smoking and random violence exploitative and voyeuristic. And who can blame them? Clark delights in serving up crotch shots of girls who look like your babysitter, or tableaux vivants of skate punks ingesting poppers by the bowlful. With Clark, there's no middle ground: either you think he's aqualung in the park eyeing the tykes, or he's an artist on par with Robert Mapplethorpe, Lou Reed and Cindy Sherman.

Clark's foray into the slightly more mainstream realm of Hollywood-style crime drama produced the funny but uneven "Another Day in Paradise" (1998). Now he's back with "Bully," the true story of a group of bored Florida teens who turn on the neighborhood terror, stab him more times than Caesar and leave him for gator bait in the Everglades. Clark makes the local Pizza Hut look like an Edward Hopper painting and gives this pack of sex- and drug-addled ruffians the full-out "Macbeth" treatment. Start squirming -- "Bully" is the mirror you don't want to look into.

In "Bully," the parents come off as completely clueless. Do you think that's specific to this story, or do you believe that is generally true of American parents?

There's that thing in this country where we just want our kids to be happy, and there's the tendency to avoid confrontation. These kids are in their rooms; the parents are in the den watching TV. The kids will get up, go make a sandwich, grunt and go back and slam the door -- just being teenagers, you know? I guess if they're in their rooms, at least the parents know where the kids are. Maybe they don't want to know what's going on in there.

In America, it's all about the kids. In other countries it's not about that -- it's all about struggle, and putting food on the table. Only in the wealth of this country do you have the opportunity to lay around and smoke pot all day, go surfing, hang out and so forth.

You make that world look so appealing that there's a real element of voyeurism involved. It's so lush that you just want to dive in.

That's the dilemma of growing up in this country. That's why it's tough on kids today to have the ambition to follow their dreams. It's so much about money now. The biggest fear of kids today is not having $3 million by the time they're 22 years old. It's really bizarre. I don't think it used to be that way.

These parents seem so oblivious, yet I suspect that when they hear politicians saying stuff like "Hollywood needs to clean up its act or we'll clean it up for them," they're probably all for it.

Yeah, you're right. Don Murphy, the producer who did "Natural Born Killers," first told me about the book. He had some good studio money to do the film with; then Columbine happened, and everyone dropped out and said, "No, no, no -- we can't make this film." I would think it would have been very topical then. But I guess the studios took the position: "We can't make this movie because it's about kids killing kids. Columbine just happened. We're afraid [Joe] Lieberman and these people will attack us. If we put it out there, and some more kids get killed, we're gonna take the heat. And Congress is going to pass laws against us. And blah-blah-blah." So they backed off, and when I decided to do the film, it was almost impossible to raise the money. Nobody wanted this film made because of the social climate. I would think it would be the opposite. Certainly, the issue is topical. Since I made the film, there has been a rash of high school shootings where it was all about being bullied. It's on the tip of everybody's tongue.

There's a lot of denial out there. People don't want reality; they want the sanitized version of your film, without the sex and drugs -- where everything's wrapped up in a neat little package with a moral at the end.

Exactly. Those are the films they're so proud of themselves for making. Take a movie like "American History X," which was like an after-school special. There's plenty of that stuff out there. So why can't I make my little movie? It's really difficult to do these films and not do this Hollywood take where everybody gets off the hook.

So what's the argument for being true to this story, and damn the consequences?

Maybe it'll open some fucking dialogue about what's really going on. Maybe all the subtext in the film will make you start thinking and hit you on a different level -- not dropping an anvil on your head and giving you such an easy way out. Film's an amazing form for that. It's almost limitless. I'm just trying to make a good film.

Why is "Bully" being released unrated?

We couldn't get an R. The MPAA [Motion Picture Association of America] shot us down. We asked them, "What do we have to do? What's your advice?" They sent back this fax (I've still got it), which says, "Our advice to America is: Hide your children." Can you believe that?

Maybe I'm a marked man because of "Kids," but it's a studio system rating, it's not the government's. If you have a big-studio movie with big-name actors, you can get away with murder, you can buy any rating you want. It's only the small, indie films like this that they pick on. It's ridiculous, it's corrupt and it's bullshit, but that's what we have to deal with.

Will the fact that it's unrated hurt the film?

It'll keep us out of a lot of venues, sure. When we did "Kids," we broke new ground. We got in the malls and the theater chains -- they'd never played an unrated movie before. So you have to struggle. The MPAA says, "You don't have to take the rating if you don't want it." But if you don't get the rating, you can't play in most of the theaters.

What about NC-17?

You can do NC-17, but no one's going to play an NC-17 movie. Unrated is better than NC-17. A movie can play in more theaters that way.

There's a lot of nudity in the film, but you shy away from male frontal nudity. Why not just go for broke if you have to release it unrated anyway?

I was trying to get an R, so I shot it that way. If you show male frontal nudity, you never get an R. My old girlfriends are always calling me up and complaining: "You never have any frontal nudity. You never show 'the gun' -- the penis." I tell 'em, in my next movie, "Ken Park," there'll be more penises than you guys can swallow. But in "Bully," I didn't even shoot [male frontal nudity] because I was supposed to have an R rating. Fortunately, [the folks at] Lions Gate [which produced the film] are such good people that they're releasing it as is. Fuck the MPAA.

What's "Ken Park" about?

It's about parents and children. You're gonna meet the parents and learn as much about them as you do about the kids. It's really a good film. I'm very proud of it. But one baby at a time, you know?

Bobby Kent -- the bully in "Bully" -- was a real bruiser in reality, what we expect a bully to look like. Why did you choose Nick Stahl, who's pretty thin and not that buff, to portray him?

I was originally looking for an ethnic actor, because Bobby is Persian. But I couldn't make that work. I met Nick, and I said, "Gee, this kid's got something. I bet he could pull this off." Nobody else thought so. You wouldn't believe the heat I got from everyone involved in the project. But I wanted Nick. Not only is he effective as a bully and menacing, but he humanizes him. You're hating this kid and thinking that whatever he gets he deserves. But when it happens, Nick turns it around, and you feel for him. Nick makes Bobby a real person.

You also leave things ambiguous when it comes to the central relationship between Bobby and Marty (Brad Renfro). Why?

I don't think anyone knows completely what was going on, and Bobby and Marty's relationship was so strange. They were doing all these different things together. They had been best friends since they were 5 years old. They were out hustling gays in the clubs, making gay porn with some of the people they picked up -- ostensibly to sell it and make money. They posed as a gay couple, with Marty doing gay phone sex and dancing in these clubs. No one saw them have sex, but there was certainly some kind of sexual tension there. But they also had sex with girls, group sex -- all kinds of stuff.

Did you speak to any of the actual kids involved?

No, they're all in the penitentiary. And once you're in the penitentiary for seven or eight years, you change so much. You're just trying to get out. And they've all got their stories down -- they think they didn't do anything wrong.

Is the generation gap you portray in the film unbridgeable? You have two teenage children -- how do you know what they're doing? Or do you want to know?

I do want to know who they're hanging with, what they're doing and what they're thinking about. I just try to open up that communication and talk to them about everything. That's what needs to be done. You don't want to blame everything on bad parenting. But that's probably the core of it right there.

What is it about youth that intrigues you?

It's such an important part of our lives. It forms us and is so key to later in life. All my early work was about me and those years. It's interesting to see the differences between how kids grow up today vs. when I was a kid. The information these kids have at an early age is totally unlike the way I was brought up, where you weren't told anything. That fascinates me. I guess I've been doing it for a while now. I seem to be not bad at it.

How do you know you're getting it right?

I'm not sure I am. I'm trying the best I can. I talk to people that age and ask them if I'm getting it right. And if I'm not, you know, maybe I'll do better next time.

Well, you know, because of "Kids" you're a huge hero to members of that generation.

With "Kids" I thought I got it right. I worked hard on the film. I hung out with kids all the time. I got the idea and the story for the film from hanging out with kids. Then I found a kid to write the dialogue. And I learned so much from "Bully" that there's another film I want to make now about being ethnic and growing up in America. I wasn't really able to explore that in this film -- being first-generation American with immigrant parents.

In "Bully," the actors you use may be older, but they're portraying teenagers having sex. How do you respond to those who would label that borderline child pornography?

I wouldn't know what to say to them. I think they're crazy. The actors are all of age in the movie. What about "Romeo and Juliet"? Aren't they 14 years old or something? They should go after that film. Didn't they have sex in that movie? So go after Shakespeare. It's ridiculous!

Shares