In the last century of American homebuilding, there may no other time when architects were so irrelevant. Less than 10 percent of single-family residences are designed by architects now, and most of the rest come from mass-produced blueprints that make entire neighborhoods identical. The small percentage of homes architects actually do design go overwhelmingly to the wealthy. And while many charities such as Habitat for Humanity address low-income housing needs, the notion that poor people could ever inhabit unique pieces of architecture anymore is almost laughable.

Somebody forgot to tell this to Samuel Mockbee.

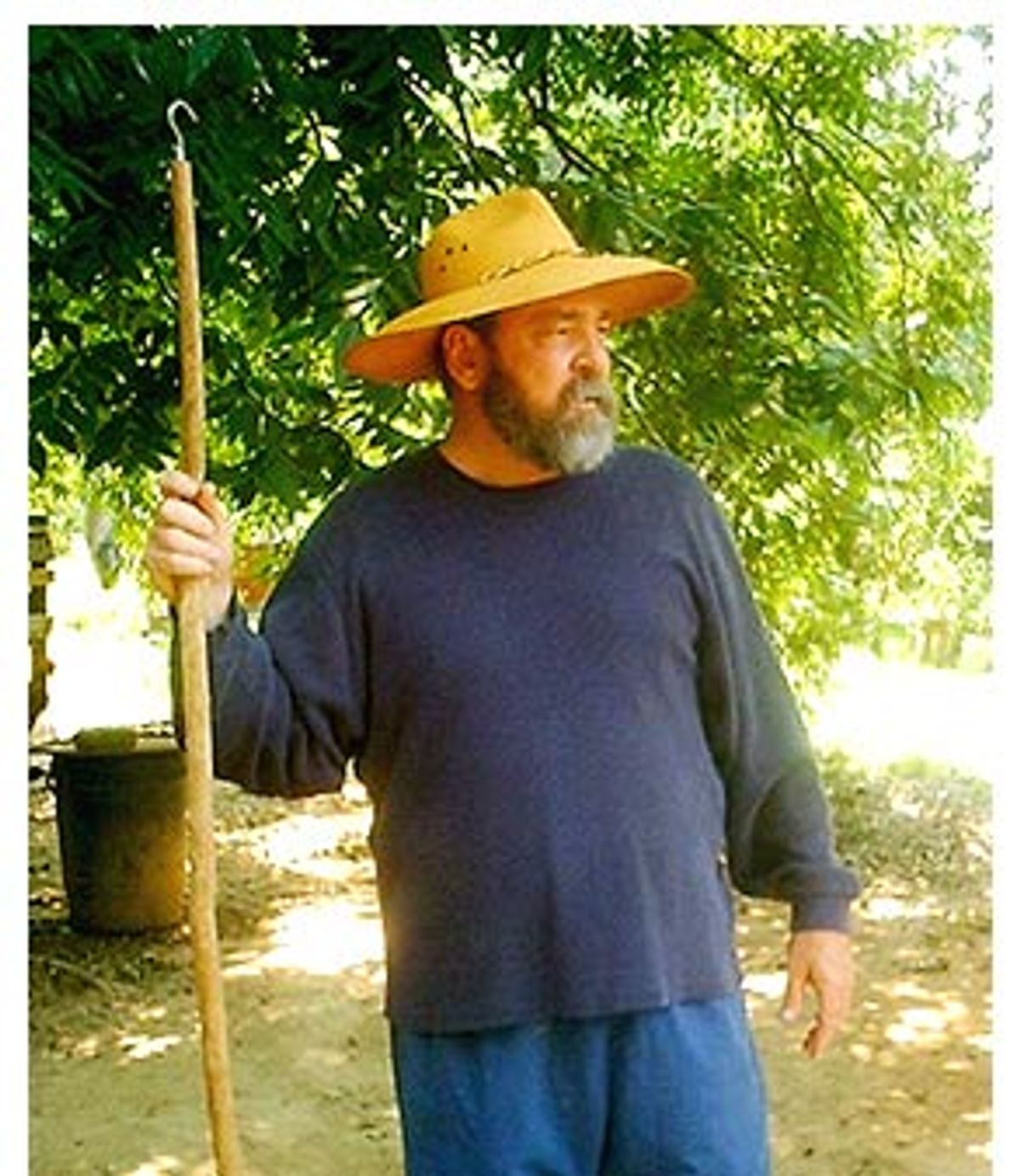

Born in Mississippi and educated in Alabama, Mockbee has spent much of his life surrounded by the extreme poverty of the Deep South. Driven to change this endless cycle, Mockbee and his partner Coleman Cocker designed a series of "charity houses" for low-income families. This was early in Mockbee's career, and the project won a 1987 Progressive Architecture Honor award. But the homes were never built. The funding simply didn't exist, and Mockbee vowed not to let this happen again.

In 1993 -- Mockbee was now teaching at Auburn University's College of Architecture, Design and Construction -- he founded what is now called the Rural Studio. This time his efforts bore fruit: For the past eight years, Mockbee has brought a group of his students to rural Hale County to design and build homes for the poor. One of the poorest regions in America, the county has more than 1,400 substandard dwellings, nearly all lacking electricity and running water. According to the 1997 Alabama County Data Book, about one-third of residents there live below the poverty level, with a per capita income just over $12,000 and an unemployment rate of 13 percent.

Often dubbed "Redneck Taliesin South" (after Frank Lloyd Wright's Wisconsin and Arizona homes and architectural studios), the Rural Studio not only fulfills an overwhelming need for decent housing but gives architecture students the kind of hands-on experience virtually all other educational institutions in the field lack. The houses are built for about $30,000 each using a variety of recycled and discarded materials (tires, bottles) and funded mostly with grants from a local power company. Designed through a collaborative process involving students and local residents, the homes boast an unconventional modern flair that incorporates the cultural vernacular of the region. They may be cheap, but these are nice houses.

In this remarkable rebuilding of Hale County, which also includes a number of public buildings, Mockbee is the glue, ensuring that his young protégés meet his meticulous standards and that the clients, perhaps for the first time in their lives, go home happy. Last year he won a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant, only the third architect (along with Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio) out of 588 past recipients to receive this award, in his case totaling $500,000.

Recently Mockbee spoke with me from his home in Canton, Miss., about architecture, public service and what he's doing with his MacArthur windfall.

How does it feel knowing your profession has been marginalized by the American home building industry?

It's a shame, because houses are the great paramour for architects, from the most successful all the way down to the most struggling. We draw them on the backs of napkins. But too often when I look at what builders and developers are doing, we're not talking about architecture any longer. We're talking about capitalism at its most obscene. The public has bought into the mediocrity and insipid attitude of manufactured and spec houses, and has given up any hope of creating homes with spirit. Real architecture does cost somewhat more. But most homes in America are built with false façades that try to pass themselves as architecture.

You've often said that all great architecture is honest.

It always has been. Architecture addresses truth and beauty and has a moral sense to it. All great art has that, too.

You cite painters like Klee, Goya and Picasso as your primary architectural influences, emphasizing the art of architecture. Yet the Rural Studio is known for advancing the profession's social and practical side.

For me art is a very personal endeavor, a way to reflect on what I'm trying to do as an architect. An architect, on the other hand, has to be an extrovert. You can't get anything built by yourself. You've got to have consultants, suppliers and a client who understands what you're trying to do. The connection is that art is a reflection of the best of who we are. One informs the other, and vice versa.

Which Rural Studio clients have been the most satisfying to design and build for?

What immediately comes to mind is the Hay Bale House we did for Shepherd and Alberta Bryant. Shepherd is about 80 years old, and unable to fish or hunt or do many of his favorite outdoor activities anymore. His wife, Alberta, who had lived with him in an old shack for 40 years, wasn't in the new house six weeks before she had a leg amputated and the other soon after. She says she doesn't know what would have happened to her had we not built that house.

But the most profound result of our efforts has been on their grandson Richard Bryant. This was a kid who didn't have anything, but because of his relations with the students -- we've watched him grow up over the eight years we've been building down there -- he's blossomed into a mature young man who's just graduated from high school, and is going to go to college. He wanted to be like them, and now he's going to be.

The Rural Studio is transforming Hale County. What would you like to see preserved?

An architect's primary connection is with people and place. You don't have to be from that place, but you have to be inspired by that place and its people. For example, the heat down here is the primary enemy. We want to be in the shade. So how our forefathers built down here -- taking advantage of shade and wind -- all those principles that were true 100 years ago are true today, and will be 100 years from now. Our great-grandchildren will still be trying to get out of the sun. But if we were in the Midwest or somewhere else that can get cold, you'd be trying to get into the sun. One has to understand the landscape one is working in and be inspired by it.

Have any clients chafed at the vibrant designs and unconventional materials being used for their homes?

That has happened to us, but not to the extent that it can't be fixed. The students have to learn to listen to the clients, and find out what their needs are. But on another level, as hard as we try to get the clients to be honest and relaxed with us, there is some apprehension that if they don't agree with us somehow we won't build it for them. I'm always trying to explain to the clients that we're going to build the house for them no matter what, and that they need to tell us what they need and want. We don't push our aesthetics onto anybody, nor do we push any values. The students work very hard to win the respect of these clients. They want to make these houses wonderful for them.

A lot of architects talk about trust being the key to a relationship with a client.

Well, sometimes that word means the architect wants the client to indulge his ego. Architects like to have their way; they micromanage too much and they think they have the answer to everything. But we are good problem solvers, and our education serves us well in attacking projects and looking at them creatively. The problem is, we often believe our own propaganda. But there are also two sides to that coin. You don't want a client who misunderstands what design and architecture are really about. Many want this faux architecture, and that drives us nuts.

Can the Rural Studio be replicated in other places?

It can be done anywhere on the planet. This last academic year we built about six projects, and every one is wonderful. There are over 100 schools of architecture in the United States. If every school were to do just one project a year, you'd have 100 wonderful pieces of architecture. But you have to have the faith that the students can do it. Academia and the profession are too incestuous. They're pussyfooting around and babbling about environment and health and code issues. It's about going out and doing it, and all that other stuff will work itself out.

Have any students gone on to do charitable architectural work like this on their own?

To get outside the status quo, there's no structure available for students to do it. We had some ex-students who did something similar to the Rural Studio in Nashville but it just about killed them, because they were doing it on weekends and that sort of thing. But what's happened to these students can't be taken away. They know the gratification that comes from serving people by using their talents. It's going to surface again at some point in their careers. I don't know when, but I know it will. It's like having a great love and losing it: They're going to want to find it again.

Do Rural Studio houses reflect your own architectural style?

I don't lift a pen or put one stroke down on those designs. But I have a high bar I expect students to reach. I make them draw and redraw, so in that sense maybe it does reflect my style a bit. At any firm the work takes on the personality of the principals, and I think that's true of the Rural Studio. But really the students do it themselves.

Do you think we should give more large-scale commissions to young architects?

I'll have to be honest about this: I feel just the opposite. Back in the '60s, we said don't trust anybody over 30. Now I say don't trust anyone under 50. If you take a look at the primo architects of the Renaissance, and the ones practicing today, you'll see that they're all over 45 and older when they do their major buildings. Frank Gehry is over 70. It takes years to accumulate the necessary abilities to produce a piece of architecture. You can do small work at a young age, but the technical aspects, the business aspects, the aesthetic aspects -- all of this you're juggling throughout your career, and trying to improve and mature. I tell my students: You may be able to start practicing two or three years after you graduate, but you're not really going to be an architect until you're 45. It's just the nature of the beast. That's probably true in medicine, law and all the professions -- except the oldest one, of course. You've got to invest in the long haul.

What are you doing with the MacArthur grant?

We're underwriting what's called the Subrosa Pantheon. In the last couple of years, several younger members of our [Auburn University] faculty have passed away, and this is a memorial to them. It looks almost like a little tornado shelter, but with roses growing on top and a fountain outside. Other than that, I'm just sort of holding my money, but I hope that perhaps next year I'll be able to take a sabbatical for some serious painting. It would really recharge my batteries.

Shares