Inside Suristan, a club near Madrid's Plaza Santa Ana, flamenco fans are assembling for a show featuring two of the city's newest generation of flamenco stars. Jeronimo Maya, a cherubic 20-year-old guitarist, and Dieguito, an Armani-clad Gypsy singer, quaff pre-gig drinks at the bar.

Heads turn as David Byrne, with an armada of Spanish record execs, parts the cloud of cigarette smoke on his way to a stage-side table. Byrne, uneasy as a nun, is surrounded by a group of boisterous Gypsies cheering the performers who take the stage.

Maya's sinewy hands fan over the strings in the first slow, sad passages of a Soleares. Dieguito, eyes closed, emits a low throaty cry that hushes the room. Byrne's eyes lock on the singer in either a moment of primal conversion or recognition of the next recording contract bonanza.

After weeks of travel through Spain sampling flamenco music in clubs, outdoor festivals and the ubiquitous private flamenco clubs called peñas, it became clear that Spain's flamenco music scene was moving toward a flashy rock-style promotion evident in Madrid's clubs.

For Donn Pohren, an American who's spent the past 45 years in Spain writing about a flamenco world that has slowly given way to Americanized commercialism, it's a sign of corruption. He's the only non-Spaniard ever awarded the title of "flamencologist" by the closed circle of writers and academics who make up the "Catedra de Flamencologia." And his books, praised by such Spanish artists as guitarist Andrés Segovia and dancer Carmen Amaya, have become underground classics fueling a quiet affair between legions of flamenco aficionados around the world and this uniquely Iberian art form.

We'd arranged to meet at a cafe in a suburb 12 miles from Madrid. The next morning I boarded a train that crawled through the tawny hills outside the city past an abandoned bullfight school, its crumbling walls a reminder of the rustic Spain where flamenco once thrived.

I found my way to the cafe and took a seat near a rack of hoofed hams dangling from the ceiling. With a predictable Spanish tardiness, Pohren appeared at my table briskly ordering a drink in Minnesota-tinged Spanish. Over a five-hour lunch accompanied by several bottles of vino tinto, Pohren told me the story of his flamenco pilgrimage.

"In the beginning I used to say my mother was Spanish, and call myself Daniel Maravilla, which did help in getting accepted," the 69 year-old author says of his early efforts to gain admittance to the then-closed flamenco world. "Now I couldn't care less whether I'm accepted or not."

Pohren has reason to be sure of his reputation these days. A few months ago he joined the pantheon of flamenco heroes memorialized by statues in the public squares of small towns dotting Andalusia. A plaque was erected in Morón de la Frontera, a town near Seville popularized in his writings, which decades before regarded him as foreign provocateur.

When he arrived in Spain, though, flamenco music was still an outsider art -- every bit as back-alley to Spain as jazz or blues was in the United States at the turn of the century. It was a music that devotees spoke of in mystical, quasi-religious terms, describing their discovery of it as a "baptism." Pohren's exploration of the flamenco cabal became an expedition through the dark umbra of Spain's alter ego on a river of wine and song.

His flamenco baptism, he says, occurred on a family vacation in Mexico City in 1947. "Wandering downtown one day I heard a guitar, singing, foot-stomping issuing from a bar, and went in. During a break I asked the guitarist what the music was," Pohren recalls. "He smiled and told me it was flamenco." Pohren remembered reading about Carmen Amaya's troupe, whose tours through the U.S. had made headlines. "I mentioned this to the guitarist. He pointed to the woman who had been dancing and singing and told me, 'That is Carmen Amaya!'"

The chance encounter with Amaya and famed guitarist Sabicas in a Mexican cantina marked the beginning of the 17-year-old's lifelong sojourn. Six years later Pohren abandoned his orderly Eisenhower-era Minneapolis neighborhood with a one-way ticket on the Queen Mary bound for Spain tucked into his pocket. His quest took him to Seville's narrow corridors, where Gypsy singers, toreros and their rich benefactors all rubbed elbows in pursuit of the flamenco life.

"I lived for a period in the Barrio Santa Cruz, in Seville," Pohren says. The compact, mostly Gypsy, neighborhood, with its jumble of narrow streets overflowing with flamenco bars, was then the heart of the flamenco world. "The flamenco scene in Seville was still in full bloom; an all night, round-the-clock affair. The cafes on Alameda de Hercules at about 2 or 3 in the morning were overflowing with flamenco artists waiting to be hired."

For decades, though, Spain had had an ambivalent relationship with flamenco due mostly to anti-Gypsy prejudice and its association with low culture. "Laws were eventually passed closing the bars at 12:30 a.m.," Pohren says. Franco's Guardia Civil, the loyal police troops recognized by their shiny "Mickey Mouse" hats, made certain that the streets were safe from the spontaneous revelry associated with flamenco. "Flamenco was too scandalous for the church and the government was making commercial ties to the states," Pohren says. "Spain's inefficiency was embarrassing. Could a country be competent if a goodly share of the working population didn't make it to work the next day or arrived sloshed?"

Pohren and other flamenco writers reverently refer to those years before the sanctions as the "epoca dorada" or golden age of the music. Pohren is convinced that modernization has spoiled not only the country, but more importantly its music. He recounts a vacation taken in a small fishing village called Torremolinos 30 years ago. A place now part of the expensive resort hotel studded section of the Costa del Sol. "I hitchhiked south. The traffic was such then that it took us a full week to cover the 400 miles."

Over the years Pohren married, his daughter was born, and he managed to finish his university studies in Madrid and along the way learn enough flamenco guitar to earn a modest living.

"Our savings were just about gone. I heard of a job opportunity for an accountant at an air base. I went there and applied and they grabbed me as their previous accountant had had a nervous breakdown trying to cope with the work. I stuck that job out three years. The only period of regimented work in my lifetime," Pohren says proudly.

"During that period from 1960 to 1963, I did a great deal of research for my books and actually wrote the first one, 'The Art of Flamenco,' mostly while working as an accountant. The book was first published in 1962 and widely regarded as the "bible" on the music, found a ready audience among growing numbers of flamenco fans in the U.K., Germany and the U.S. The book was quickly followed by "Lives and Legends of Flamenco," an opinionated and lively history including intimate sketches of the many flamenco performers he had met in his travels.

Finally Pohren left his day job and accepted an offer to open a private flamenco club in a cellar in Madrid's calle Echegaray. The club, near where Suristan now attracts large crowds to hear flamenco, failed after a year. Pohren packed up and headed back to Andalusia where his adventures began.

A remote two-story ranch house, called a finca, became available and he saw an opportunity to continue his pursuit of the flamenco life. His third book, "A Way Of Life," is a memoir of life on the ranch which gradually became the nexus for enthusiasts from around the world. Pohren assiduously collected flamenco characters from the surrounding villages who mixed with clients from New York, San Francisco and other points on the globe in an atmosphere that was part old-world flamenco fiesta and part cosmopolitan cocktail party. "We were dedicated to offering pure flamenco. Commercial flamenco is banal and insincere -- it's good business, but not authentic folk art," Pohren says.

"The scene appealed to professional people, lawyers, doctors, scientists. We had two judges over the years. We had lonely divorcees, writers, poets, music buffs and so forth. The finca brightened Morón de la Frontera's normally quiet existence."

Word of the finca along with the popularity of his first book quickly made the country inn a destination for die-hard flamenco fans and the fashion-conscious folk music crowd alike. Pohren had brought the world to a small town outside Seville with mixed results. Ironically, the town that would pay him tribute 30 years later, viewed the sudden popularity of the old finca and the influx of exotic tourists with suspicion. "The town was absolutely sure of one thing, the finca was slated to be a cabaret featuring prostitution and flamenco," Pohren says.

"There was also the indirect activity caused by the finca being in operation," Pohren says. "Many aficionados came in search of the flamenco way of life and stayed in town. After a time, it became a hippie stopover in the hash route from Marrakech to Europe." An affable and prodigious drinker, Pohren is heroically nonconformist about most things except drugs.

Pohren presided over the nonstop flamenco partying, which occasionally spilled over into the otherwise quiet town, like an unflappable scientist watching an experiment go berserk.

"On one occasion a dance teacher from Paris came with her students -- 10 girls. The town was still living in the dark ages then, town folk dressed somberly and any act slightly out of the ordinary caused eyebrows to rise," Pohren says. "The French girls were unconcerned about that and wore miniskirts and halters. Young men followed them around in the streets in silent wonderment."

For the local guitarists and singers it was free drink and food and cash at the end of the night. The Gypsy performers, who often died penniless despite having made a small fortune in their lifetimes, welcomed collecting their first regular paycheck.

"The flamenco juerga, or jam session is the only vehicle for true flamenco expression," Pohren says. "We hired artists from out of town such as Manolito de Maria, Monolo Heredia, Juan Talega, El Farruco, all great artists in their own right."

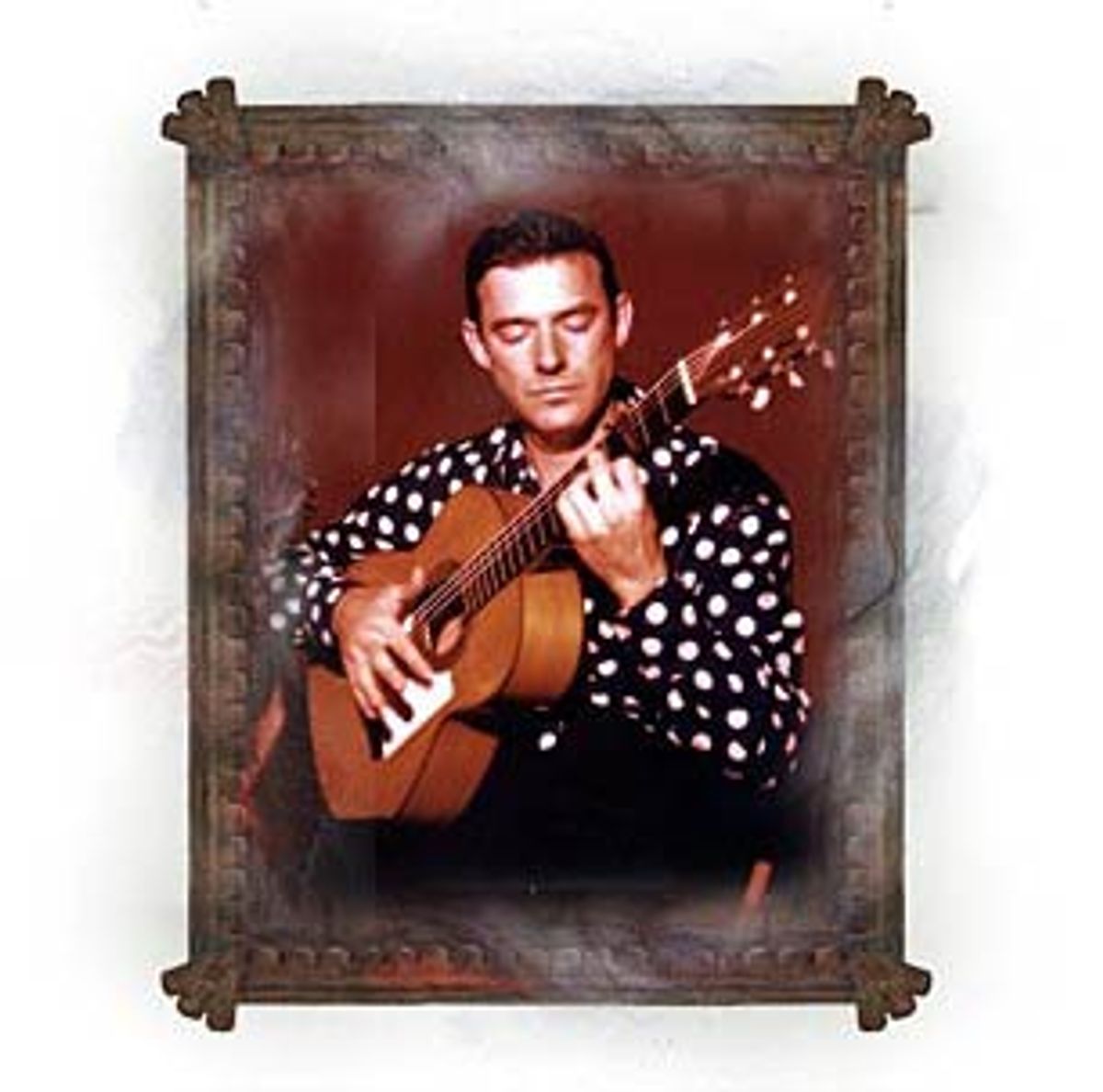

The star at the finca became Diego del Gastor, a princely local Gypsy noted for his simple and emotional style of guitar playing, who would later become a legend and icon to flamenco fans and musicians around the world. "He played mostly private parties. The very essence of this man emerged through his playing. He arrived directly at the soul of flamenco without frills or bullshit," Pohren says. Diego's death in 1973, commemorated by a bust in a small park and a street bearing his name, spelled the end for the finca.

I mention the popularity of the flamenco stylings of the Gypsy Kings, and Ottmar Liebert's diluted new-age noodling as well as the Spanish television shows featuring flamenco, suggesting that it may have helped boost the art in recent years. I tell him of the subtle incursion of flamenco as background music for truck commercials in the states, and the celebrity of Joaquin Cortez, the shirtless Gypsy dancer whose romance with Naomi Campbell made tabloid headlines.

"There are people who will think that Ottmar is the real thing," Pohren replies, with a hint of disgust. The advent of American-style record deals hatched in Madrid clubs, Pohren believes, is like the infiltration of McDonald's in the country's ancient squares: an evil he can't prevent but one that he won't accept. "Today's affluence is deadly to the flamenco way of life," he says.

Dorien Ross, author of the acclaimed novel "Returning to A," which recounts her immersion in the flamenco world, credits Pohren with inspiring her first trip to Spain. "He was the first adult I'd met who was really like a big boy," the New York author recalls about her eventual meeting with Pohren. Ross' novel recounts the time she spent at the finca and the nearby town learning to play guitar with Diego del Gastor. Her journey at 17, began with a letter to Pohren and ended with her boarding a plane clutching a map he'd drawn on a cocktail napkin.

"I devoured his books," Ross says, "it was like falling into another world." She shares Pohren's conviction that those days marked the end of an epoch. "Being in Morón de la Frontera in the '60s was one of those gifts life occasionally offers that changes the course of the river."

Shares