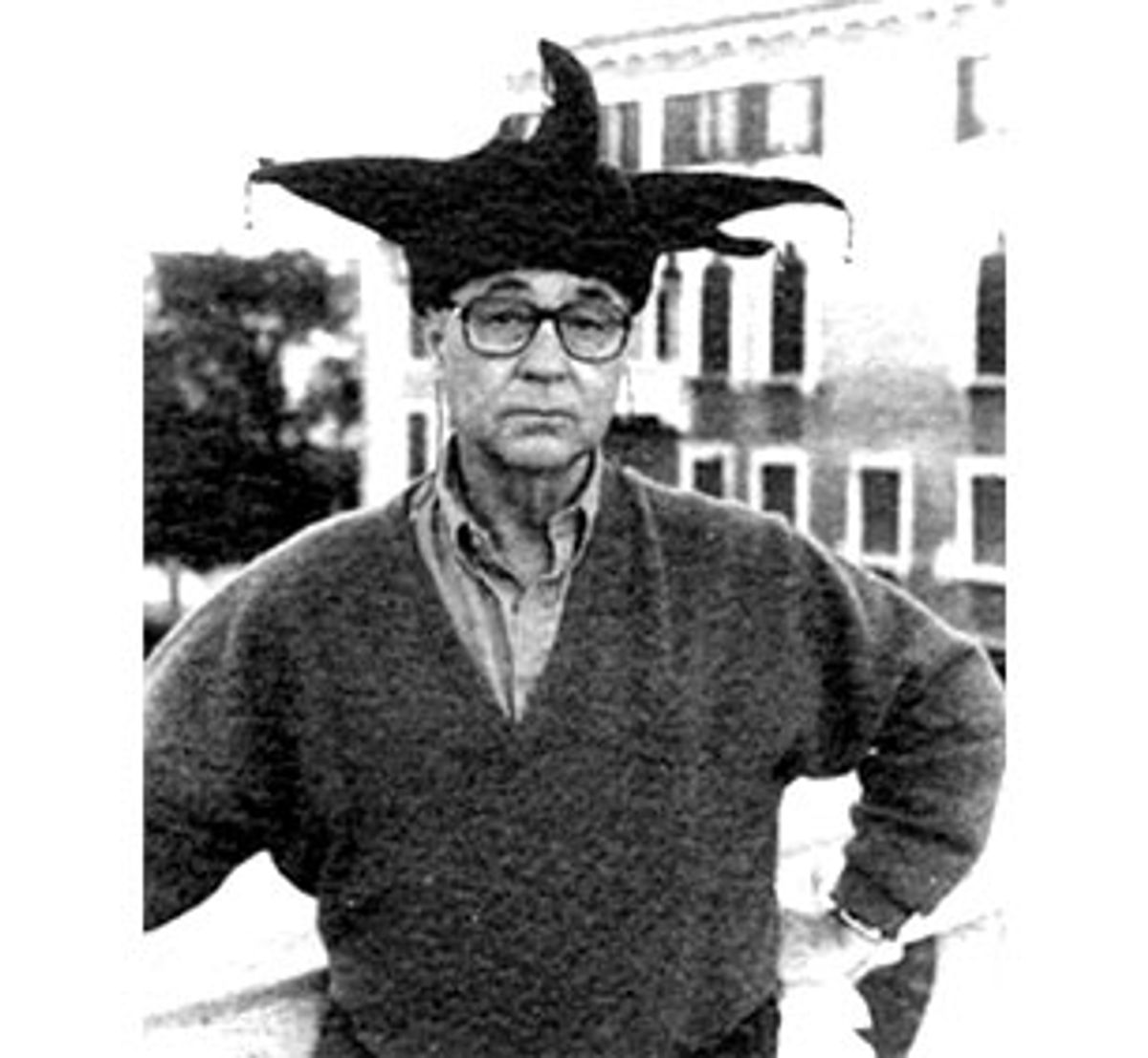

"Museum Watching," Elliott Erwitt's latest picture book, is a pronounced departure from the whimsical fare many have come to expect from the famous photographer. Though still attuned to the odd moments and peculiar social spaces that grace all of Erwitt's personal work, the book has a larger, elegiac feel.

Erwitt, who is possibly more famous now for his amusing and widely reproduced photos of dogs than for the handsome balance of work he's done during his almost 50 years with the Magnum photo agency, haunts museums of all types around the world "at idle moments." His main goal is to observe the people he finds in them. "For a photographer," he writes in the book, "rather than fly casting, it's like shooting fish in a barrel." Most of those he photographs are immersed in a cultivated absorption of the past, and there is not one cute canine in sight.

Like his contemporary, Robert Frank, Erwitt brought an essentially European sensibility to the American scene. (He was born in Paris to Russian parents and escaped the Nazis as a teenager, settling in Los Angeles.) Whereas Frank's work mirrors his dislocation, exposing a morbid groundlessness in American social spaces, Erwitt looks to make a bemused peace with strange lands. "Everyone's got to be somewhere," he observes in "Museum Watching." The theme of most of Erwitt's published work seems to be the sometimes silly ways people -- and dogs -- make themselves feel at home in the world.

In our telephone conversation, Erwitt is reticent talking about his past or much about his pictures. Asked about his 1961 assignment on the set of "The Misfits" (photographing actors Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach and Thelma Ritter along with screenwriter Arthur Miller and director John Huston), he says only: "It was another job, but an interesting one -- one of the better ones, full of interesting people." A book of "Misfits" stills taken by him and other Magnum photographers will be published soon.

Of his early attraction to photography, Erwitt gives a characteristic reply: "Everybody's got to do something ... I'd been on my own since an early age and I thought I better find something to do to buy biscuits and stuff. From high school onwards I was earning my way with photography, one way or another, working in darkrooms and taking pictures of weddings, neighbors' children and so on."

Clearly, he was doing more than just earning his way. On a trip to New York to show his work, the young Erwitt gained the regard of three of photography's most powerful overlords: Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, Robert Capa at Magnum and Roy Stryker at the Standard Oil photo library. Steichen included several of Erwitt's pictures in MoMA's monumental 1955 "Family of Man" show, Stryker hired him as a staff photographer and Capa promised a membership at Magnum after Erwitt's two-year Army hitch. He has been with the agency since 1953.

Since then, Erwitt has kept true to his roots, eschewing color photography, outside of client work, for the classic nuances of the black-and-white palette. "I don't think of it as old-fashioned or new-fashioned," he says. "It's just the way I work. Aesthetically I prefer it, and I can control it -- print it and so on."

When talking about a small note at the front of the book stating that none of the photographs had been electronically altered, a hint of steel enters his gentle voice: "I put that in all my books. I'm almost violent about that stuff -- electronic manipulation of pictures. I think it's an abomination. I reject it all. I mean, it's OK for selling corn flakes or automobiles or for taking pimples out of Elizabeth Taylor's face, but it undermines the thing that photography is about, which is about observation and not about manipulation of images."

While it can be argued that all photographs are manipulated (photographs are altered in the traditional darkroom process, photographers emphasize certain compositional elements over others and so forth), Erwitt's passion for the direct gaze and decisive moment, unmediated by further calculation, is his trademark. "Museum Watching" is a book by an artful observer about observing art, and, as such, is something of an indictment of our modern addiction to the juiced-up image in the hopped-up frame. It celebrates a way of regarding the world that is rapidly losing traction in contemporary culture.

Not all the museums in the book are dedicated to art. Buddhist temples, aerospace displays, ancient ruins, historical sites and aquariums also figure in the mix. Somber notes are touched in the few photographs taken at Auschwitz in 1964 and last year at Cambodia's Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. But "Museum Watching," with its witty sequencing of images separated by geography and years, and its warm appreciation of the human equation, favors, like photography itself, the side of light over darkness.

In brief written passages introducing sections of the book, Erwitt muses on such topics as how to take pictures where photography is forbidden (use a quiet camera, frame when no one's looking and cough when you trip the shutter), the plight of museum guards ("Next to elevator operators, they have the world's most boring job") and his enjoyment of mummies and other stuffed remains ("Wax museums are a poor substitute in comparison"). Between the lines is an appreciation of all endeavors that strive, however unsuccessfully, to rise above the dull and everyday.

He brightens when asked about his favorite museums: "I like museums in Berlin a lot," he says, "especially in the eastern part. They're extraordinarily good. One I like is the Franz Hals museum in Holland. That's interesting because it's his own house, a 17th century house with paintings in it, so you sort of get the feeling that you're stepping in that atmosphere. And I like the Rodin museum in Paris and the Frick collection [in New York].

"The most awful museums are in China. They have magnificent stuff on display and just the worst way of displaying it. They just don't spend money on lighting and installation. I guess they have other priorities at the moment."

Toward the end of "Museum Watching" Erwitt observes that "all museums are interesting, even when they are not."

"Anytime anybody presents something to the public it's interesting by virtue of that," he says, "even if it's terrible. It's a manifestation of somebody's intention, and that's always interesting."

Shares