In 1982, after smoking three packs of Camels a day for 30 years, Sonny Barger, the founder of the Oakland Hells Angels motorcycle club, was diagnosed with cancer of the larynx and his vocal cords were removed. On the way to the operating room, he smoked one last cigarette. "They cut a hole in the front of my neck," he writes in his new autobiography, "Hell's Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell's Angels Motorcycle Club." When he recovered, he had to learn how to talk again. "I put a finger over the hole," he continues, "and vibrate a muscle in my throat."

As I talk with Barger at a movie producer's office in West Hollywood, two bodyguards -- Pete from the Dago chapter (San Diego) and Bobby from Cave Creek (Arizona, where Barger now lives) -- sit on a couch across from us and look on from behind their shades. Also present is Fritz Clapp, Barger's lawyer and associate, a non-Angel out of prep school and Dartmouth, by way of the Marines. After a while, when it is evidently clear that I am not an actor in some greater play involving Barger's very life, they leave.

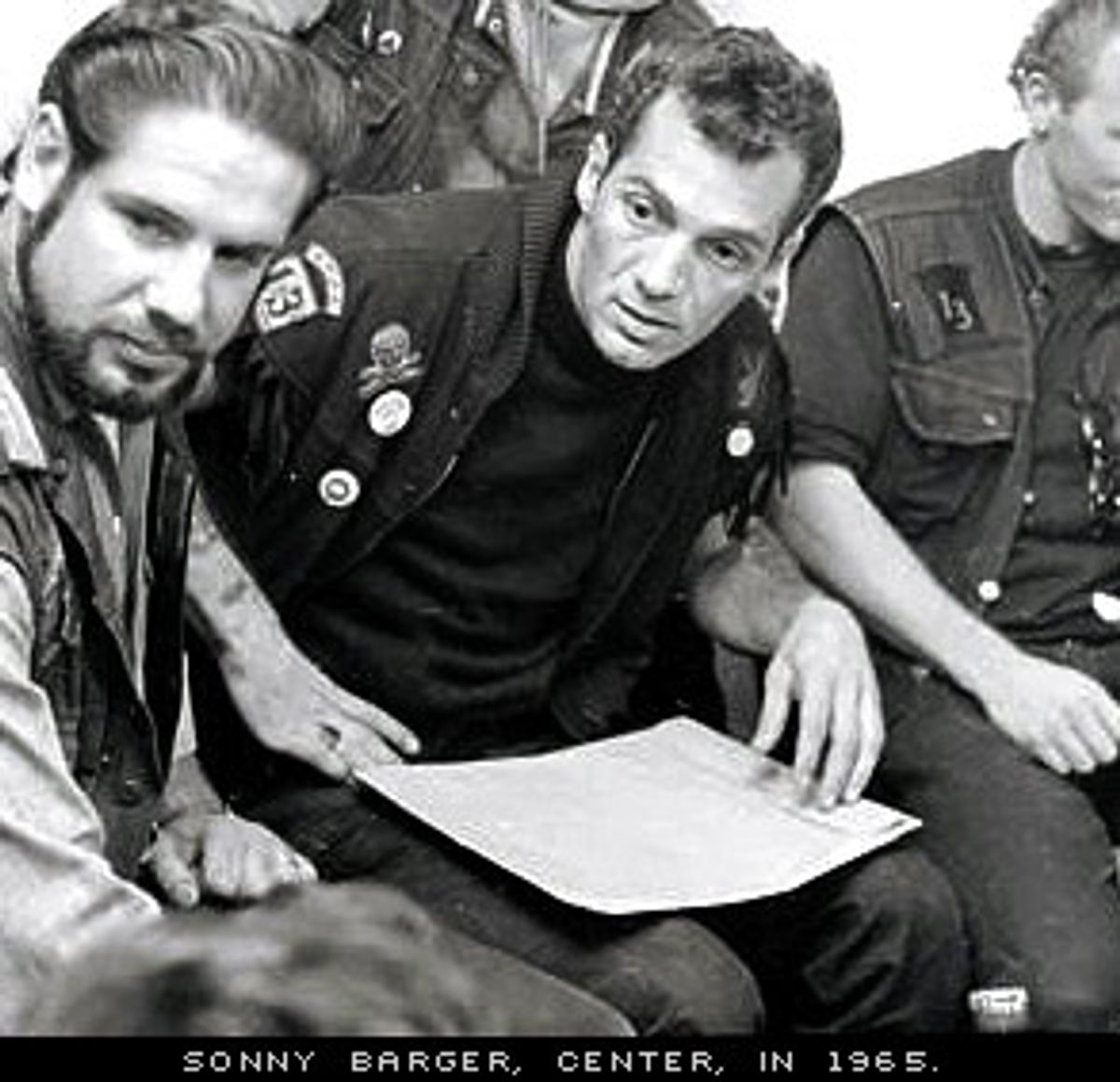

At 61, Barger, still stocky and buffed, moves with the quick edge of a street-fighter. I ask him how he heads into the wind with a hole in his throat and pipes that don't work the old-fashioned way. He explains that since his operation, he has worn a full-face helmet (though he is still not in favor of helmet laws). His bike has a windshield. There is an "obvious economy of speech," a phrase from his book, yet one senses that back in the day, before the cancer, his rap was quite engaging.

Barger is a perpetual and metaphorical fugitive, ever on the road, except for when he's been in jail, time which amounts to a total of 13 years. "They can't scare you once they put you in jail," he says. His rap sheet has become a calling card, and he includes it at the end of his book, as others might list sports stats. The arrests -- 21 of them -- began in the '50s for drunken driving and continued through the next 30 years, with Barger charged with, among other things, attempted murder (charge dismissed), kidnapping (time served), drug possession (disposition unknown) and racketeering (59 months).

The mythology around him has swirled accordingly. He's either a bad guy as in really cool, or a bad guy as in he really is not a nice person, depending on one's value system. Either view has attracted women and journalists. All previous accounts of him are inaccurate, Barger says, referring to Hunter Thompson's "Hell's Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga" (which he agrees is well-written) and Yves Lavigne's atrociously written informant-based reports called "Hell's Angels" and "Hell's Angels: Into the Abyss."

Now, with the publication of "Hell's Angel," Barger is telling his own story. To promote his book, he has embarked on what might be called a road jaunt, though he now sleeps in hotels and friends' homes instead of stopping wherever he chooses and taking a pill to knock himself out as he used to. But there's still an element of bad in the book tour.

The tour began in Chicago on Michigan Avenue at a Barnes & Noble, and it was not lost on some observers that it had kicked off in the heart of Angels' enemy territory, the Midwest and particularly Illinois -- the home turf of the Outlaws, a rival club. Was this a ballsy strike on Barger's part, or did the publisher start the tour here to take advantage of a package deal on a room at the Hilton? Who knows. If the Outlaws ever have a book signing in Oakland, I guess we'll learn the answer.

Yet turf matters not to the devoted; often, wherever Barger has gone, from bookstores to Harley dealers, he's encountered a writer's wet dream: selling 500 to 700 copies at a pop, as legions of his fans wait in long lines for a papal visit and blessing. The book's first printing of 45,000 copies has sold out and there have been several additional print runs. It's hovering at No. 15 on the New York Times bestseller list, and is under option to producer Ben Myron with Tony Scott set to direct and Barger and Clapp to produce.

"Maybe it'll be good," Barger says. "I like what Tony has to say about riding. He used to ride, you know. In England. But I have no idea who should play me. The only actor I like these days is Jim Carrey."

In his book, Barger takes on his enemies, informers, cops, the RICO act and, to this gal's delight, the Rolling Stones. He blames the Stones for the famous incident at Altamont in which a fan pulled a gun and was killed by an Angel. I've always hated the Stones; I know a good garage band when I see one and the Stones ain't it. Barger likes to tell this story about Altamont: "The crowd was waiting all day to see the Stones," he recalls, "and they were sitting in their trailers acting like prima donnas ... They got the crowd worked up and they used us to keep the whole thing going. All that shit about Altamont being the end of an era was a bunch of intellectual crap. It was the end of nothing."

It's true that eras do not begin and end with music festivals, yet Barger's disclaimer may have come too late; as it has been decreed in the press, Altamont may forever remain the epitaph for the '60s.

Barger is no stranger to the fable factory. All his life, as he tells it, he has been misunderstood by the culture that both builds and feeds off his myth. Pegged as a bad boy, he does not shy away from the characterization. He readily talks about his run-ins with cops, Angels who have been killed in fights or bike accidents, years of drug abuse, the toll that it took on the people around him, particularly his second wife who after years of doing speed with him finally left, but not before passing him off to the woman to whom he is now married. He laughs about how the cops are still, and probably forever, on his tail.

At a book signing in Albuquerque, N.M., someone was arrested for carrying a firearm. "There are undercover cops at all my signings," he says. "The store in Albuquerque had two parts -- one was a bookstore, the other was a restaurant which sold wine. You're not supposed to bring a firearm into a place that sells liquor so that's what they used to arrest the guy, even though the place was also a bookstore." At the signing in Glendale, Calif., evidently a high-ranking member of the police department had parked his car outside the Harley dealer to keep an eye on things, but sent an emissary in to buy an autographed copy of Barger's book. "Cops are like children," he says.

One could say that Barger was first busted as a baby. When he was born, his father, Ralph Hubert Barger Sr., worked in California's Central Valley, laying down pavement for Highway 99, drinking and sleeping in motor courts in the accompanying little towns. Sonny's mother, Kathryn Carmella Barger, would take Sonny and his older sister, Shirley Marie, to visit Ralph, shuttling "like gypsies" between Oakland and Modesto, Calif., on a Trailways bus. When Sonny was 4 months old, his mother ran off with the bus driver, landing in Twentynine Palms, Calif. (once-and-future way station for the country's wanderers), leaving her son with a babysitter in Modesto who alerted the cops. Came the call from the police department: "Mr. Barger, we've got your son down here."

When old enough, Barger began to escape. His first runs were to San Francisco -- on his 26-inch Schwinn one-speed with coaster brakes. Later, after a stint in the U.S. Army and a series of dead-end jobs (including a shift on a potato chip assembly line), he hooked up with other war vets who had seen the world and weren't happy with the one they found back at home. They set up shop in Oakland, and enacted a set of rules that comprised a fun house mirror image of military structure: on California runs, weapons will be shot only between 0600 and 1600 hours; Club will furnish patch which remains club property; there is a five-dollar fine for fighting among club members ("Hardly a deterrent," Barger says); no spiking the club's booze with dope; no messing with another member's old lady. ("Big-time rule," says Barger; "There are 50 million women in the world, which leaves only a few thousand Hells Angels old ladies you can't fuck with.")

But in talking to Barger, there is the sense that he would like to make yet another escape -- from the myth around him, the one that he's out on the road, selling. He prefers Japanese bikes to American, says they're better, but continues to "buy American." He talks about encroachments on freedom. "They're taking away our guns," he says. He lives in Arizona because it has fewer laws than other states. "I love the desert," he says. "It's like California used to be."

Barger continues to name other signs of what he sees as impending fascism. "Did you know that the Army's helmets look exactly like Nazi helmets in World War II? They'll never tell you that but take a look. They're getting us ready," he says. Ready for what? "Well, this is how it starts. Little things." I ask when the Army adopted the helmets. "Ten years ago," he says, and then trails off as the answer itself seems to indicate that the helmet style, like Altamont, has not heralded the beginning or end of anything, except as Barger then points out, "They're Kevlar; maybe bullets bounce off them better."

The following evening Barger appears at a book signing at Beyond Baroque, an ever-hip literary establishment in Venice, Calif. About 100 have come for the meet-greet-and-buy (far fewer than the throng that had shown up earlier at the Glendale Harley dealership). Dennis Hopper introduces Barger, calling him his hero. The connection isn't clear: Hopper's street creds appear to come simply from his appearance in "Easy Rider," which Barger writes is a movie about drug dealers who happen to ride motorcycles. But no matter, flanked by the bodyguards from Dago and Cave Creek, Barger tells a quick anecdote about an old friend and a Chevy El Camino and then signs books for his fans: members of the Vietnam Vets MC, the Chosen Few and other Angels who have made the pilgrimage.

"This is the first time I've bought a book," one says. Barger poses for pictures and listens intently as people recall meeting him at this or that rally -- Sturgis '85 or the river, last year. Later, outside, in the dark, he flirts with a few girls, then jumps on his bike, heading for Modesto to count more coup in the form of books, going from zero to really fast on the sidewalk and then into the streets, gunning those Harley pipes, and that sweet badass sound -- siren echo of his own gone voice -- lingers in the night like a strange American lullaby as he escapes again into the mists.

Shares