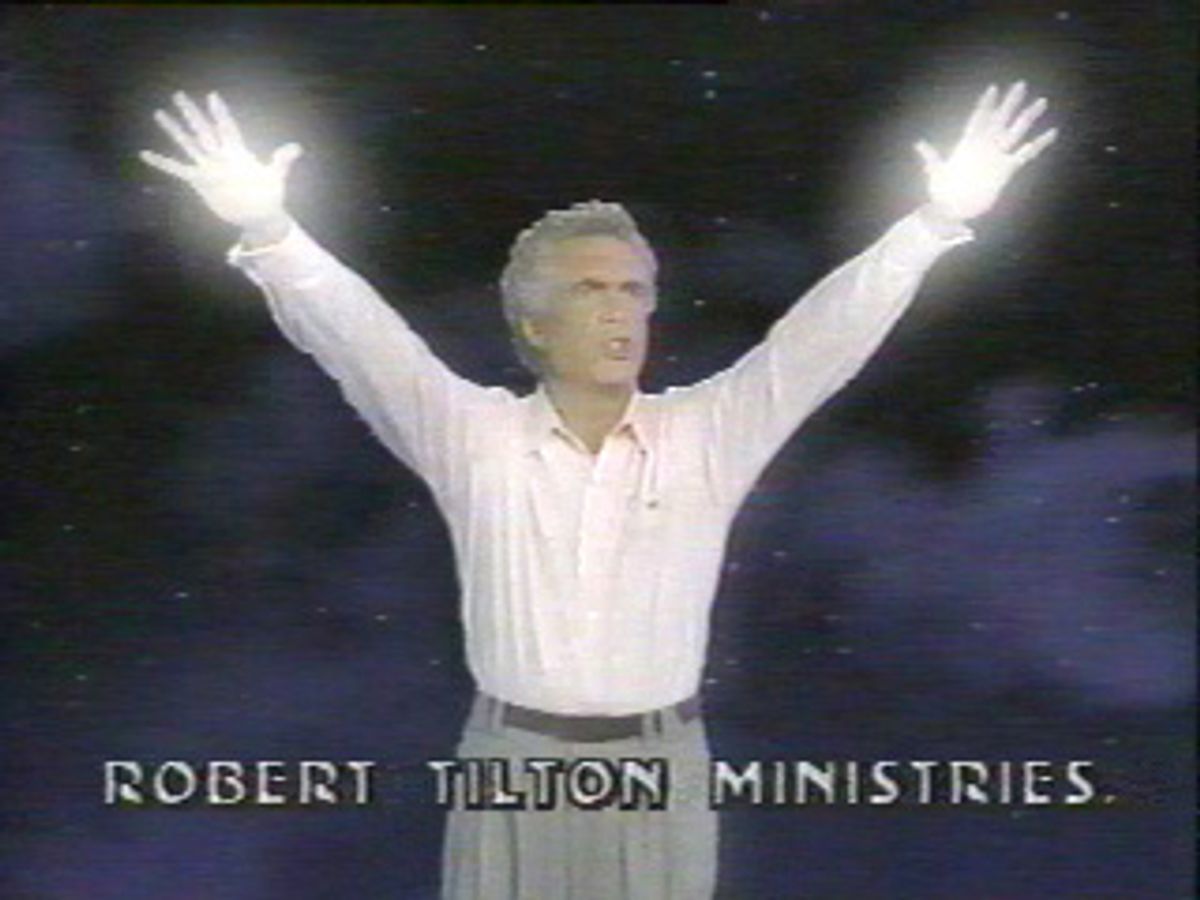

Robert Tilton, the shameless profit prophet, is back on the air. Known to those entertained by televangelists in the early 1990s, Tilton's unscrupulous antics are legendary. He has tangled with law enforcement, leading Texas Attorney General Dan Morales to tar Tilton with "raping the most vulnerable segments of our society -- the poor, the infirm, the ignorant ... who believe his garbage." Amazed at Tilton's Lazarus shimmy, I double-checked the channel. To my amazement, the self-described "apple of God's eye" had been snatched from media purgatory by the libs at Black Entertainment Television.

Although he avoided the media frenzy that dogged his predecessors Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart, Tilton was a heavy in his day. At its apex, his empire reaped $80 million annually, before an ABC investigation put the screws on his allegedly fraudulent outfit in 1991.

Tilton's march toward televangelist titanhood began in the early 1970s. According to "Primetime Live," Tilton was then struggling through college, enamored of getting hogged up on Saturday night as a prelude to local tent revival meetings. He and his cohorts would run down front, imploring the hucksters to "save" them along with the rubes. Listless at university, Tilton took the yuks to heart by establishing his own canvass-based road show. A decade in the wilderness paid dividends with the establishment of Word of Faith Family Church north of Dallas. This sterile edifice became the headquarters of the wildly popular nationwide program "Success-N-Life" -- a faith-based "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire."

Tilton's spiel was hardly novel. He borrowed heavily from Pentecostal "prosperity gospel" teachings and specific biblical passages that implied a monetary and spiritual quid pro quo from God if "vows and seeds" were "paid and sown." Tilton was an innovator in one sense: He was the first TV preacher to follow up saturation television exposure (he was on the air in all 235 American TV markets) with a massive and sophisticated direct-mail operation. Each envelope contained a "gift from God" -- "miracle" cornmeal packets, holy oil, faith rings, cutout angels -- designed specifically to create an obligation to reciprocate financially.

Clearly recognizing that his target audience was generally poor and gullible, Tilton commiserated by claiming that God hadn't sent him to "the fat cats of this world." This shrewd pitch (he often recalled his own past travails) came by way of a quirkily engaging delivery. Breaking off trancelike midsentence to speak in tongues was standard -- "sonda basoya" being the minister's favored bit of faux-Sumerian sputtering.

Tilton also built credibility through homespun -- and scripted -- testimonials: A hapless couple would recount their mishaps on cue while one of Tilton's well-scrubbed cronies prodded and nodded as needed. Without fail, the vignette would conclude with newly prosperous followers lounging by their dandy new pool or suburban hearth, earnestly crediting Tilton's "miracle plan for man."

The final segment of "Success-N-Life" was ritually subdivided between serial readings of hefty, incoming vows and spontaneous, vicarious healings. In a boilerplate charade, still practiced by Tilton's heir Benny Hinn, the evangelist would press his eyes shut and run off a laundry list of ailments that God was healing that very moment. One minute the "demonic spirit of cancer" was vanquished; the next a nebulous "growth in the head" was cured.

Alas, Satan eventually intervened, in the admittedly plausible form of Diane Sawyer. ABC newsmagazine "Primetime Live" mercilessly dressed down Tilton in a two-part exposé. Central to the exposé was footage of dumpsters behind the ministry's Tulsa, Okla., bank, filled to the brim with the "prayer requests" upon which "Brother Bob" had solemnly pledged to act. The ministry was more judicious when processing freshly solicited $1,000 "vows of faith."

Fuming, and likely well aware of the devastating blow dealt his spiritual shell game, Tilton responded shortly after "Primetime's" piece with a priceless tirade. Gone was the "aw shucks" delivery, in its place a junkyard dog. In reference to the trashed letters and kitsch: "Somebody musta stole them prayer requests and planted them there," opined the ghoul. His smooth, P.R.-crafted explanation for multiple mansions around the country: "Ain't I allowed to have nuthin'!?"

Then, addressing why he had spent thousands on a hair weave and plastic surgery, Tilton got surreal. He launched into a roundabout explanation of how ink had seeped into his bloodstream during his relentless "laying of hands" for prayer requests, which somehow resulted in capillary damage to his lower eyelids. Thankfully, Tilton chose not to justify why his proclaimed Jesus-inspired retreat to the mountains for fasting and contemplation took place at a Colorado resort via Mercedes, from whence he was captured on film lugging a large TV. At the end of the diatribe the fun-loving wackiness returned: "And until we meet again, happy trails; I love that song, don't you? Marte [his soon-to-be-dumped wife], would you come over here; you're so sweet and obedient." The theme music then cut in, playing what would be a swan song -- or so it appeared.

After the revelations, disgusted followers filed a dozen lawsuits. One of the plaintiffs, Mary Turk, said she had avoided seeking medical treatment for colon cancer because she believed doing so would indicate a breach of faith in God. Other followers reported having sent in wedding rings and portions of their welfare allotment.

Tilton subsequently left town to dabble in "demon blasting" with an obscure sect in North Carolina. Another marriage, this one to a former Miss Tallahassee named Leigh Valentine, went down the toilet. By the mid-'90s, it seemed Tilton's last stand was the dismissal of his laughable libel case against ABC.

However, by mid-1997, according to an article by Sean Rowe in the Miami New Times, Tilton had turned up in South Florida, sipping cocktails incognito on various marina verandas while plotting a comeback. One South Florida entertainment industry source familiar with Tilton's secretive outfit commented to Rowe:

"These guys are geared up for real, and they're here to stay ... They're a real piss to hang out with. They're just good ol' Texas boys. They like to smoke cigars and drink brandy and have a good time on South Beach. Tilton told me once, 'I just want to come here and be left alone.'"

By 1998, Tilton was living high on the hog again, having cemented his ties with BET. He was raking in nearly $1 million a month.

These days, Tilton is as brazen as ever. He now culls decade-old "Success-N-Life" testimonial footage, much of which depicts newly affluent and pleased-as-punch African-Americans. The program invites African-American gospel singers to further legitimize the outreach. Tilton's clairvoyant claims that "God doesn't want you to drive a clunker or live in a trailer, he wants you to have nice clothes, nice furniture" continue unabated.

Tilton's direct-mail operation is in full swing again. To date, his most ghastly pitch comes in the form of a poster depicting himself with an intent Impala-selling expression on his face and a thought bubble above his head: "God spoke two words, Millionaire Potential!" Another recent miracle "point of contact" contains a red heart in an envelope with the message "Place it inside your billfold for a financial blessing and slip both your wallet and this sealed heart under your pillow." A "seed gift" of $20 is suggested as a down payment on a "vow" of anywhere from $250 to $1,000. In 1998, Washington Post reporter Hanna Rosin asked BET about the propriety of a financial alliance with Tilton. BET spokeswoman Michelle Moore glibly retorted that the network "does not see it as its responsibility to monitor the content of shows it has no role in producing."

"It's a serious ethical question for [BET President Robert] Johnson," says Jeffrey Haddon, a professor at the University of Virginia who studies TV evangelists. "A network that pats itself on the back by saying it serves the black community ought to stop selling time to people who take advantage of them."

Ole Anthony, a Dallas televangelist watchdog whose research informed much of the "Primetime" exposé, conservatively estimates Tilton's current annual take at $24 million. Anthony doubts "that any vehicle could compete with BET for Tilton's budget. It delivers his target audience [poor minority members, primarily in large urban centers] at a cost of about $1.2 million per year for five hours a week."

Anthony also points out that Tilton has "aired only two new shows in 2000. He has a backlog of shows in the can, and since he says the same thing over and over to a constantly changing audience, why go to the expense and effort to do daily broadcasts? This leaves Bob with a cash machine and total leisure time to enjoy the fruits of his 'ministry.'"

In response to these and other issues, BET -- whose parent company, BET Holdings Inc., was purchased last week by Viacom -- continues to insist that it does not bear ultimate responsibility for what goes on the air if the network is not involved in the production of the show. That sort of argument didn't work for Nike when the company tried to deflect criticism for its "independent contractor" sweatshops.

Nevertheless, Rob Santwer, BET's director of corporate communications, insists that Tilton's show is "acquired programming" that "we don't handle." The time buyer for Tilton is Rosenheim Associates in Connecticut, which appears to make a project out of getting disgraced televangelists on the air.

When asked whether BET has any misgivings about Tilton, Santwer concedes, "It's the kind of show you watch for a minute and turn the channel." On why BET doesn't look for an alternative to Tilton as an infomercial, Santwer says, "That's a decision made above me." Could Johnson find "Success-N-Life" as amusing as I do? After all, the show is funny. Tilton remains compellingly entertaining -- a virtual self-parody with more than a passing resemblance to the Joker in "Batman" -- far surpassing the "reality programming" of "Survivor" or "Big Brother."

The P.R. rhetoric from BET, throatily touting a commitment to black empowerment, is called into question when it televises this rather fleshy embodiment of "the man" coast to coast. Both BET and Tilton appear to share a credo, summed up by a trenchant German saying: "Erst kommt das Fressen, dann die Moral." First we feast, then we moralize.

Shares