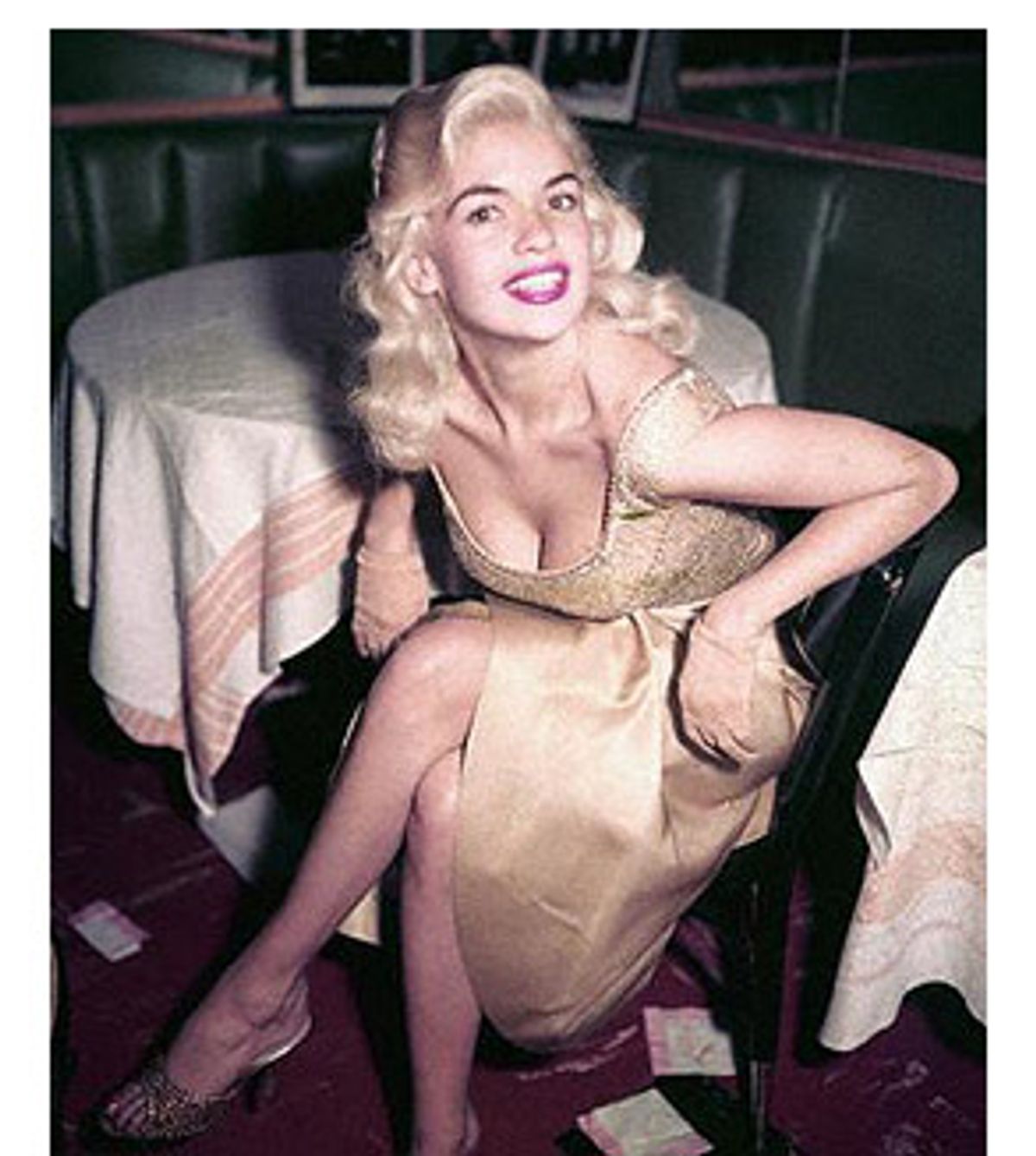

In 1967, several months before actress Jayne Mansfield drove into a cloud of insecticide to meet her destiny, a London newspaper took the full measure of the movie star and found her breasts to be 2 inches larger than the 44 inches she was then claiming for them.

"Ooh!" she squealed in delight. "I'm a big girl now!"

Her reaction, absurd, even pathetic to the post-feminist ear, was pure Mansfield. More than 40 years before consultant guru Tom Peters spoke of the free-agent movement and business magazine Fast Company wrote of the "The Brand Called You," Vera Jane Palmer of Dallas had grasped self-promotion's essential points to fashion herself into the hottest dish in the Cold War. From 1955 until the early '60s, Mansfield reigned as Hollywood's gaudiest, boldest D-cupped B-grade actress. "The working man's Monroe,"they called her. Her enormous breasts and baby doll voice embodied the '50s American male's fantasy of female sexuality: curvaceous, flirtatious and grateful for a man's -- any man's -- attention. Shipped stacked and stupid guaranteed or your money back. (For the record, Mansfield advertised her I.Q. as 163, but such intellectual pretensions were a nonstarter. Even she admitted her public couldn't care less. "They're more interested in 40-21-35," she said.)

She appeared in films such as "The Girl Can't Help It," "Promises! Promises!" and "Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?" Her face became a favorite news wire photo, with "voluptuous" as the usual cutline adjective. But by 1965 it was over. The "big girl" had become a desperate woman. "An old bag" was how uncharitable mop top Paul McCartney described the then 32-year-old actress to Playboy that June. Mansfield's last two years were a sad decline. The press dried up. Movie offers vanished. Her days consisted of fifths and fists as alcohol and an abusive boyfriend, Los Angeles trial lawyer Sam Brody, left their marks on the famous figure. Mansfield was reduced to rounds of telethon and dinner theater appearances. She was returning to New Orleans from just such an engagement in Biloxi, Miss., on June 29, 1967, when she died. Her car's driver, his vision obscured by a mosquito sprayer, ran under a tractor-trailer. The collision peeled back the car's roof -- instantly killing the driver, Mansfield, Brody and two of the star's Chihuahuas. Even now the rumor persists that she was decapitated. She wasn't. "Scalped" is the most polite word to describe what happened.

Mansfield and her gruesome end serve as the bimbo's Ozymandias -- a warning against attaching one's public persona to something so fickle as cultural tastes in allure. Britney Spears, Pamela Anderson, Christina Aguilera and other pulchritudinous stars: Look upon this ruin, ye mighty, and despair.

What destroyed Jayne Mansfield? Forget agents or pop historians. The answer may lie with the alchemists of capitalism -- the brand managers. Marketing consultant Matt Park, a former General Mills product manager, is no stranger to packaged goods; he specialized in Betty Crocker potatoes and Gold Medal flour. To Park, Mansfield's sad fate is a case history of a product that failed to evolve with its customer base.

"At that time the culture was moving from the '50s to the post-Kennedy era," Park says. "The entire nation was reevaluating what was ideal, what should change. The start of the antiwar, anti-military movement, the rise of feminism -- these were significant shifts in the public's attitude and mind-set. Mansfield never made the transition."

In marketing parlance, Mansfield the brand had lost her "resonance." Her audience no longer wanted what she was selling. Hollywood's other blond bombshell, Marilyn Monroe, had made an unexpected, if posthumously fortuitous, career move by dying early enough (in 1962) to avoid a similar fate. Mansfield was not so lucky; she overstayed her welcome. When American male sexual fantasies turned from torpedo-breasted pinups to braless hippie chicks somewhere in the mid-1960s, Mansfield was doomed. The new competition was, at the time, unlikely stars like flat-chested model Twiggy or raw-voiced rock singer Janis Joplin.

Sex in the '60s was "a closer version of reality," says Guthrie Dolin, a principal in Department 3, a San Francisco branding firm whose clients include Logitech and Microsoft's Ultimate (formerly Web) TV. In 1967, he said, no one needed an unattainable woman resembling those on the back of smutty playing cards when they had an entire summer called Love.

Nor could Mansfield depend on her acting to sustain her, being, at best, an enthusiastic thespian. Others were less charitable. "Dramatic art in her opinion is knowing how to fill a sweater," cracked Bette Davis. Mansfield had always shrugged off the criticism. "I decided early in life that the first thing to do was to become famous," she said. "I'd worry about acting later."

"What's intelligent about what Jayne did was that she recognized she could pick the shortest route to fame," Dorin says. Mansfield cottoned immediately to the importance of visual shorthand in a world already saturated with images. "You could look at Mansfield and in three seconds know what she was all about," he says. "She was a great advertisement for sex."

Her breasts became her icons. Their public introduction occurred in 1955. Photographers, waiting to cover a Jane Russell film premiere, were gathered around a hotel pool ogling Mansfield, who was frolicking in the water. Suddenly she lost her top in a carefully planned "accident." Her unleashed anatomy sent the paparazzi into frenzy. By the time the press conference began, the photographers were out of film and Mansfield's breasts had joined Detroit's tail fins as a symbol of '50s excess. Her ascent was swift. When she appeared in the Broadway musical "Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?" later that year, the New York tabloids ran so many pictures of her, at least one said there'd be no more of them until further notice.

Mansfield developed more visual iconography: an all-pink mansion called the "Pink Palace" with pink rugs and bathtubs filled with pink champagne, furs and cars. It was a choice, says Dolin, that defused the threat of female sexuality for a 1950s audience unprepared for it. "Colors have emotional connotations," he explains. "Pink is sex -- not the 'red' of adult sex, but girlish."

Finally, there were packs of muscle-bound escorts and Chihuahuas, and always the cleavage -- precariously packed inside dresses that left no room for lunch. Divorced from her first husband, high school sweetheart Paul Mansfield, she married weight lifter Mickey Hargitay, a Hungarian refugee. Along the way she had five children (Mariska Hargitay of TV's "Law and Order" is Mansfield and Hargitay's daughter), acquired another husband, Matt Cimber, and was crowned Miss Fire Prevention, Miss Electric Switch, Miss Nylon Sweater and Miss Geiger Counter, among dozens of other titles. She turned down the title "Miss Roquefort Cheese." It didn't sound right, she said.

"One of the most difficult things to do from a branding perspective is keep a consistency of message but maintain your relevancy over time," says Park. "You're constantly trying to fiddle with the area around the core message, adapting it and altering it to keep up with changes in the competitive environment." Changing tastes are a great danger to a can of cola -- or to an entertainer.

In the 1960s feminism was altering perceptions and tastes of what was sexy and where and when women could be sexual. Sexiness no longer depended on helplessness or huge boobs. Fast overhauls and a new wardrobe weren't enough for Mansfield. Nor will it be, says Park, for today's ingenues.

"Take Britney Spears," he says. "She must be cognizant of her audience. As Britney's audience ages, she has to be in tune with what they're willing to accept her as. As the teens get older they'll switch from the boy and girl band music to something more aspirational. They'll want the alternative bands as they get into high school and college age. She'll have to grow with them. Can she? I think it's going to be a tremendous challenge; when you look at the history of teen groups, almost none of them have successfully made it into the world of adult music."

Dolin cites that famous chameleon Madonna as the pop star best known for changing with the times. "She's a mother," he says as an example. "She makes that important. She's given different facets of herself to people. You feel like you're getting a sense of her. Jayne Mansfield was 'you've got pink, you've got champagne, you've got Chihuahuas.' Who was she? She didn't reveal herself, so people couldn't get a real sense of her. She had no history."

That does not mean Mansfield is forgotten. Her trademarks have since been appropriated by other personalities. Dolly Parton, Pamela Anderson and Anna Nicole Smith owe varying parts of their careers to their willingness to exploit their figures and, at least in Parton's case, to a considerable artistic talent. Los Angeles personality Angelyne appears to be Mansfield's clone, right down to her pink Corvette. This summer Reese Witherspoon's Chihuahua-toting, pink-thinking character in the film comedy "Legally Blonde" has brought Mansfield's image into the 21st century, with intelligence -- not cleavage -- as her most prominent attribute. Meanwhile the Web is rife with rumors about Mansfield's Pink Palace. The Sunset Boulevard mansion is allegedly haunted by her ghost. She materializes poolside, in a bikini, of course. Brand recognition, it would appear, is everything, even in the afterlife.

Shares