Coleman Barks, 21st century poet, likes to point out that Jelaluddin Rumi, 13th century poet, is both the bestselling poet in the United States and the one most often played on Afghan radio stations. Given the current situation, it's unlikely anyone will be able to confirm the latter. But it is fair to say that one thing currently binding these two warring nations is a poet born in a time when neither country existed.

It would be a dissapointment if there wasn't a story about how Barks became the country's most popular Rumi translator. Rumi lore is studded with stories marking beginnings and endings and revelations. Nothing gradual happens to mystics. Life-changing events are spontaneous and total. Insight flashes; Teresa de Avila falls into an ecstatic trance, a crash, an explosion and everything is different.

The story of how Barks, Southern-born poet and University of Georgia English professor, became a Rumi scholar begins in 1977. On the night of May 2, Barks dreamed he was lying in a sleeping bag on the banks of the Tennessee River, near where he grew up. Suddenly a flash of light lit up the sky and, as Barks describes in the introduction to his new book, "The Soul of Rumi": "A ball of light rises from Williams Island and comes over to me -- revealing a man sitting cross legged with head bowed and eyes closed, a white shawl over the back of his head. He raises his head and opens his eyes. I love you he says. 'I love you too,' I answer."

One year later Barks found the same figure in waking life: The man was a Sri Lankan Sufi saint named Bawa Muhaiyaddeen who would instruct Barks -- who did not and still does not speak Farsi, the Persian dialect in which Rumi originally wrote -- to pursue his translations.

If you are not generally inclined to believe stories about prophetic dreams and other supernatural events, then you are also probably not a Rumi fan. Stories of the mystical and miraculous don't constitute all of Rumi's writings, but they're a part of it. For better or for worse, they've helped cement his stubborn association with the new age movement. But a suspension of belief, or at least the ability to appreciate the symbolism of a far-fetched story, gives life to Rumi poems.

This particular genre of life-changing events has a familiar structure; Rumi's own account of his genesis is made up of similar components: protagonist, mentor and one puzzling proclamation that divides life into before and after.

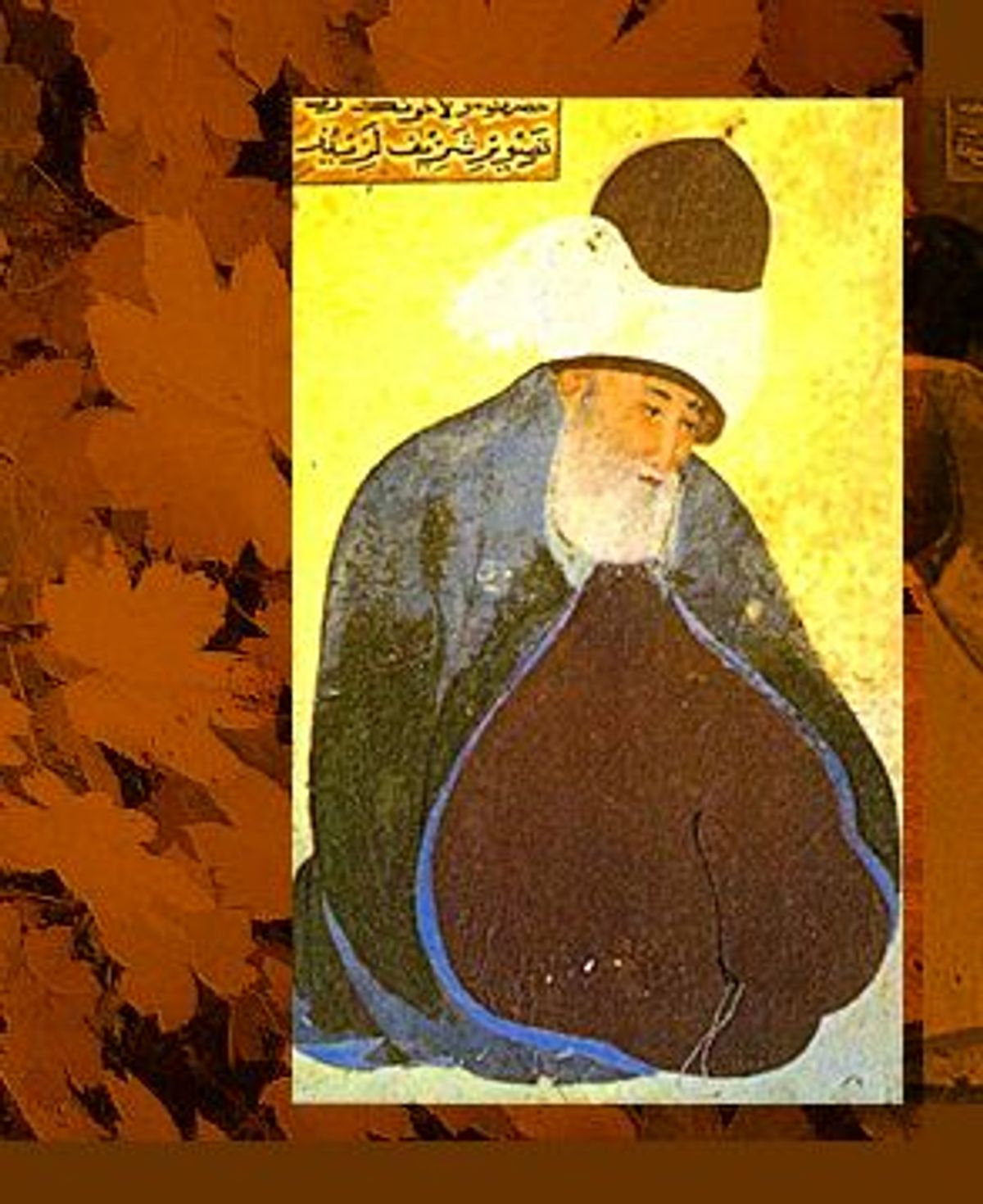

Rumi was born in 1207 in Balkh, a city in what is now Afghanistan, to a long line of Islamic theologians and poets. When he was a child, his family moved from Afghanistan to Konya, Turkey, presumably to get out of the way of the invading army of Genghis Kahn. Rumi became a scholar, a poet and a teacher as his father had been.

One day in October 1244, Rumi was sitting by a fountain, reading his father's writings, when he was visited by what Barks calls an "ecstatic soul" -- an Islamic mystic named Shams of Tabriz. Shams approached Rumi, grabbed the manuscript from his hands and flung it into the water. When Rumi protested, Shams asked what must have sounded, even then, like a rhetorical question: Would Rumi prefer to live with God, or continue reading about him? The drenched papers, said Shams with a miraculous flourish, "will be as dry as they were." And he was right.

If life, not paper, is the path to the divine, Barks' translations may be closer to Rumi's ambitions than those produced by scholars of Farsi, the Persian dialect in which Rumi originally wrote. Barks deals very little with the original Farsi: He starts by comparing existing English translations, which he then rephrases into his own. Often this means giving up the rhyme and tempo of Rumi's original Farsi, but it allows Barks to bring the poetry a jauntiness and modernity. Rumi's jokes become funnier with Barks behind the wheel. Thus we get: "Someone born deaf has no more use for high notes than newborn babies for a fine merlot." It's a style Barks hinted at when he criticized a contemporary, Farsi-speaking Rumi translator who "uses words like 'unfathomable' a whole lot."

Barks, 64, is a big man with dark circles under his eyes. He's a little disheveled and wears a full white beard. We sit down to talk at a restaurant in Oakland, Calif. "I once met the living end of Rumi's lineage," he tells me. "Twenty-eight generations have traced their line down through. He was in Atlanta with the dervishes and he sat me down at the table to give me this beautiful book, this gift, and he said, 'What religion are you?' and I just threw up my hands and he said, 'Good.'" Later Barks says, "Love is the religion and the universe is the book. So if the universe is the book, that is your life as you're living it, that's the universe for you. That's your text."

He sees the Taliban as differing little from Bible-thumping Christian fundamentalists. "This is a bunch of brainwashed terrorists who are literalists and who are insane. They seem like scholarly narcissists. They seem like kids. They don't seem to have ever met a fully mature woman or man; I don't think they know one. They haven't been initiated into the mysteries of compassion. They're stuck in some literal way like a verse-quoting Southern Baptist would be. There are fundamentalists in every religion," Barks says.

I ask him, "How can it be that millions of Americans are picking up the same poetry books perused by the inhabitants of a country we're currently dropping bombs on?"

"Well, he reaches such a wide expanse," Barks answers. His audience "can include very devout Quranic scholars who hear his poems as some commentary on verses in the Quran. We can find Muslims and talk truly to them. That's how both countries can love the same poet. And he can also appeal to people like me, just gnostics who only accept their own experience rather than any revealed interpretation of it through a book. He has always been able to embrace that wide band of seekers."

One reason Rumi reaches audiences this diverse is that he's rarely very specific about who he's talking to or, for that matter, what he's talking about. Here he is, in Barks' translation, on the idea of the "beloved," a concept that includes virtually all of the visible and invisible world:

I belong to the beloved, have seen the two

worlds as one and that one call to and know

first, last, outer, inner only that

breath breathing human being.

It's likely this emphasis on the abstract over the specific is what keeps new agers and Muslim fundamentalists thumbing the same pages. Still, Rumi was born a Muslim. He lived as a devout Sufi Muslim, took a pilgrimage to Mecca, acted charitably in his community and fulfilled the duties of a Muslim. But woven through his poems is the insistence that sectarian differences don't really matter -- a conviction Barks shares. Like Rumi, Barks is less interested in religious distinctions than he is in the religious experience.

"Those who divide people from the ones who love the Quran and ones who love the Bible," Barks says, "and ones who love the Torah -- it's not part of that. There's no exclusive document that reveals. It's a family of people who are trying to learn how to love. And that's a very broad version of religion, but I think it's a valid one."

Even by Islamic standards, there's nothing terribly radical about that. It's a basic, if frequently ignored, aspect of the Islam that Muslims are instructed, by the Quran, to live in peace with Jews and Christians (if not actually befriend them). "Surely," reads the Quran, "those who are Jews and Christians -- they shall have their reward from the lord, and there is no fear in them, nor shall they grieve."

To make name distinctions, says Rumi, is to miss the point. He makes his point with a fish metaphor -- Barks gave one rendition: "One of [Rumi's] jokes about what theology is, he says it's like we're a school of fish getting together to try and discuss the possibility of the existence of the ocean. There is no separation. So don't try to find names for it."

But on another count, Rumi could hardly be more at odds with the Islamic fundamentalists. While fundamentalists preach a strict observance of the Quran's every injunction, Sufis, like all mystics, find God in experience rather than in scripture. Ecstatic communion is what Rumi was after, and that kind of experience was not going to happen at the mosque or reading the Quran. Rumi didn't want to throw his books in the fountain, until he learned that the message in them would have to come from within himself.

Despite all this, it's not so unreasonable to think that, as you read these words, there is on the radio somewhere in Kabul or Mazar-i-Sharif, a voice reciting the poetry of Jelaluddin Rumi, Afghanistan's local prodigy. And if that person, or one of us, went looking for a poem to describe the agony of war, we might come up with this one.

I've broken through to longing

Now, filled with a grief I have

Felt before, but never like this.

The center leads to love.

Soul opens the creation core.

Hold on to your particular pain.

That too can take you to God.

According to Rumi, not only does our "particular pain" take us to God, it is God. And in Barks' translations, there's nothing in the world, its worst and best, that isn't holy. Barks explains, "And if that's true then every kindness and every healing, as well as every disease and cruelty and every terrible sudden screaming is all God. It's all divine."

This is one way to look at tragedies on the scale of the Sept. 11 attacks. Another way is to simply wish they hadn't happened and maybe consider dumping a God who would have allowed it. The question of why any God would allow tragedy on this scale fills entire shelves at the library, but I asked Barks anyway, at which point he took another bite of his sandwich and said, "Maybe Rumi is just trying to describe his ignorance. He feels that it's a sacred universe, and yet he feel that there's terrible things happening and he can't deny that they're part of it."

Art is a place we often go looking for advice when we've run out of other options. And what's there, inevitably, isn't an answer but a reflection of the suffering we already feel. On this point, Rumi, reduced by grief to simple, unmiraculous reflection, does a pretty good job.

The tomb

Looks like a prison, but it's really

Release into union. The human seed goes

Down into the ground like a bucket into

The well where Joseph is. It grows and

Comes up full of some unimagined beauty.

Your mouth closes here and immediately

Opens with a shout of joy there.

"It's a mysterious thing what the soul is," Barks says. "No one knows what the soul is. But I think it's the thing that makes symbols, makes stories, it's that overflow part of the human psyche that generates 'War and Peace.' There was no need for 'Twelfth Night,' or 'As You Like It,' it just flowed out of Shakespeare. Same way with Rumi's poetry; it was all spontaneous. It was part of the work that he was doing with the learning community, he spoke it. Didn't write it down. He spoke it and then a scribe took it down. And then Rumi would look at the pages and make alterations. But mainly you can say it is jazz, made up at the demands of the moment. It's as spontaneous as a day. And keeps on happening. So certain characteristics of the soul might be that it's generous in its ability to generate things, it's joyous, innately playful and grieving; it's very connected to grief."

Shares