Word of Ken Kesey's death came in under the radar last weekend, which is surprising considering the way the ebullient author rode into the American circus.

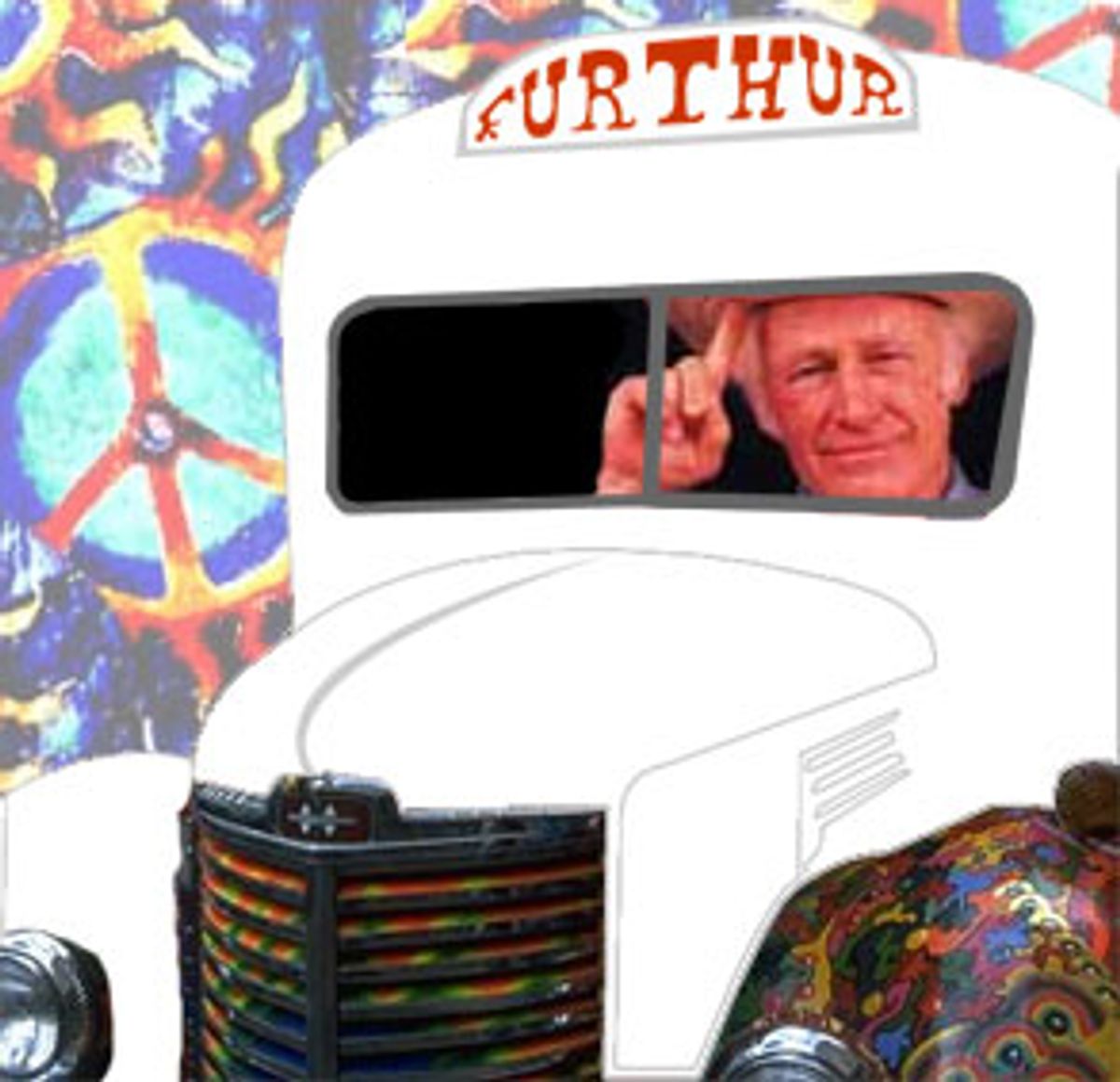

It's easy to imagine him playing his own best-known character, Randall P. McMurphy, the bull-goose loony in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," or see him as Hank Stamper in the 1971 film version of "Sometimes a Great Notion," just by squinting a little at Paul Newman. But when I think of Kesey, I think of him on top of that bus, the same old International Harvester he left to the weeds outside his Oregon farm instead of the Smithsonian Institute.

Here's one of the luminous snapshots captured in Tom Wolfe's "Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test," the book that chronicled the 1964 cross-country trek of Kesey and his Merry Pranksters with the same love and attention to detail Stephen Ambrose employed to limn the voyage, toward a different frontier, of Lewis and Clark.

"Going through the steams of southern Alabama in late June and Kesey rises up from out of the comic books and becomes Captain Flag. He puts on a pink kilt, like a miniskirt, and pink socks and patent leather shoes and pink sunglasses and wraps an American flag around his head like a big turban and holds it in place with an arrow through the back of it and gets up on top of the bus roaring through Alabama and starts playing the flute at people passing by ..."

But Kesey wasn't headed west. The Oregon-born farm boy turned hepcat author was headed in the opposite direction, toward New York and the old America that had no idea what to make of him and his bus's stated destination: "Furthur." While "Cuckoo's Nest" had been published to mostly enthusiastic reviews just two years earlier, "Sometimes a Great Notion" met a much more mixed reception. It was too outsized and over-the-top, some critics complained, too lyrical and lusty -- all together too western. Besides, declaring Kesey's second book a failure meant that the East Coast Literary Establishment (as that posse was invariably referred to then) wouldn't have to create a new category for the writer after all. He could go down in literary history dismissed as one of those branded with, and broken by, literary promise.

Pity. For it is that very East-West split that fuels "Notion." The story centers on a rivalry between two half-brothers -- one college-educated and sophisticated, the other defined by native wit and instinct -- fighting over the same woman. As Kesey told an interviewer at the time, "The two Stamper brothers in the novel are each one of the ways I think I am." And for all its iconic status, "Cuckoo's Nest" looks a little stiff and one-dimensional these days: McMurphy's martyrdom is too obvious and symbolic, as is Big Nurse's smiling malice. "Notion," for all its baggy patches and unfinished jazz riffs, has the feel of real life -- the kind that sticks its thumb in your eye. In an age when organized labor was still largely revered in fiction, the Stamper family battled with the union; and just as tree-saving became a national passion, Kesey gave us loggers for heroes.

And pranksters. The Stampers are a family of jokers who salute the town they're battling with by tying their father's severed arm, middle finger erect, to the mast of a logging boat. McMurphy expressed much of his disrespect for authority in tricks and sight gags, like the World Series game the inmates "watch," sans picture. The Merry Pranksters themselves aspired to be sort of holy fools, as fellow Prankster and lifelong friend Ken Babbs reminded the assembled at a funeral service for Kesey in Eugene on Wednesday. "It's important to know what a prank is," the eulogist said, standing before the author's painted paisley coffin. "Kesey defined it as something that doesn't hurt anyone. It has to be illuminating and it has to be funny."

The book on Kesey has always been: link between the beats and the hippies. His peripatetic adventures, including exile in Mexico, echoed Kerouac's (the two met, badly, on that very trip in '64), and his bus driver was Neal Cassady, for crissakes, the very model of Kerouac's great hero, Dean Moriarty, in "On the Road." And everything Kesey and the Pranksters did was consciously imitated by countless longhairs in the years that followed, from the amount (if not the quality) of LSD consumed to the vagabond existence. (The Pranksters created the prototype for Deadheads before their Acid Test house band began calling itself the Grateful Dead.) But like most convenient summations, that thumbnail sketch of Kesey is too small for the big picture.

"On the Road" is one of those great wannabe books, in which the author identifies with the man of action who is the story's true hero. Kesey dodged that tomahawk in a most unexpected way: He made himself the hero of his life. The best writing he did after the '60s ("The Day After Superman Died" and "Now They Know How Many Holes It Takes to Fill the Albert Hall," about the deaths of Cassady and John Lennon, which were included in Kesey's 1986 book, "Demon Box") blurred fact and fiction. The protagonist, if not named Kesey, was his spiritual twin, plunked down in similar circumstances. And though these infrequent pieces didn't have Norman Mailer looking over his shoulder, they proved that the old boy still had it, and just chose to do something else with it. Some still contend that the critics' failure to fully embrace "Notion" put the zap to Kesey's head, and that his decision to quit writing then and live the life of a media outlaw was, in the words of fellow Stanford Writing Program grad Gordon Lish, "avoidance behavior." His pursuit of celebrity, followed by celebrity's dogged pursuit of him, cost him the time and space a writer needs to experiment, and to fail. (Kesey himself confessed that he at times felt haunted by his failure to write another book as good as the first two.)

But in his desire to be part of the show rather than the audience, Kesey heralded a change in behavior that busted the seams of the '60s, a whole generation weaned on TV, only to discover that there was nothing good on. "I'd rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph," the novelist told Wolfe in an attempt to explain his decision to quit writing. It's a sort of Patrick Henry cry of the turned-on era: Give me electricity or give me death. (Is it any wonder that Dylan was the Pranksters' default musical choice?) Before he arrived at Stanford, after his stint at the University of Oregon, Kesey tried his luck in Hollywood for a year, hoping to break into the movies. How apt that the Pranksters --armed with microphones, cameras and sound equipment -- were ostensibly trying to make their own movie as they drove across the country, holding a mirror up to the startled passersby.

It was a stoned, ridiculous idea, of course. Like much of the '60s. And the fact that nothing ever "came of it" -- fellow Prankster and lifelong friend Ken Babbs is editing that footage to this day -- the fact that there was no Hollywood blockbuster or ABC miniseries to show for it all when it was over, is all the more delicious. In his own way, Kesey understood that getting there was more than half the fun, it was the whole game.

That game included some timeless values -- in an age when the family was challenged and nearly disintegrating, Kesey was always an ardent family man -- and he knew he was as equipped to play it as anyone, and to lead by example. It's a pity he didn't write more, but what a joy that he gave others so much to write about. "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" is still, to my thinking, Wolfe's best book, an exploration of an inner moonscape and the astronauts who sought it that took the chief spaceman as seriously as you could take anyone wearing a pink kilt. After a frigid blast of '50s cool, Kesey pointed toward something infinitely warmer, slightly dangerous. "Unless you get up near that very precipice where you're likely to make a fool of yourself," he said, "you're not showing much of how you feel."

Thanks for the show, Captain.

Shares