In Dhaka, the sprawling capital of Bangladesh, a small museum on a quiet side road commemorates the country's war of liberation -- a war that, though now dimly remembered, stands among the greatest genocides of the 20th century.

The museum houses a numbing collection of tragic artifacts from that 1971 conflict -- shirts and sandals of some of the nearly 3 million Bengalis the Pakistani government managed to kill in their convulsive yearlong campaign to retain control over the eastern portion of their country. Maps of mass graves were left behind by the Pakistanis, who then as now enjoyed the patronage of America, in this case because Henry Kissinger thought they were geopolitically significant. Oh, and hanging on the wall of the museum is an LP jacket, and inside it the record of a fundraising concert in Madison Square Garden.

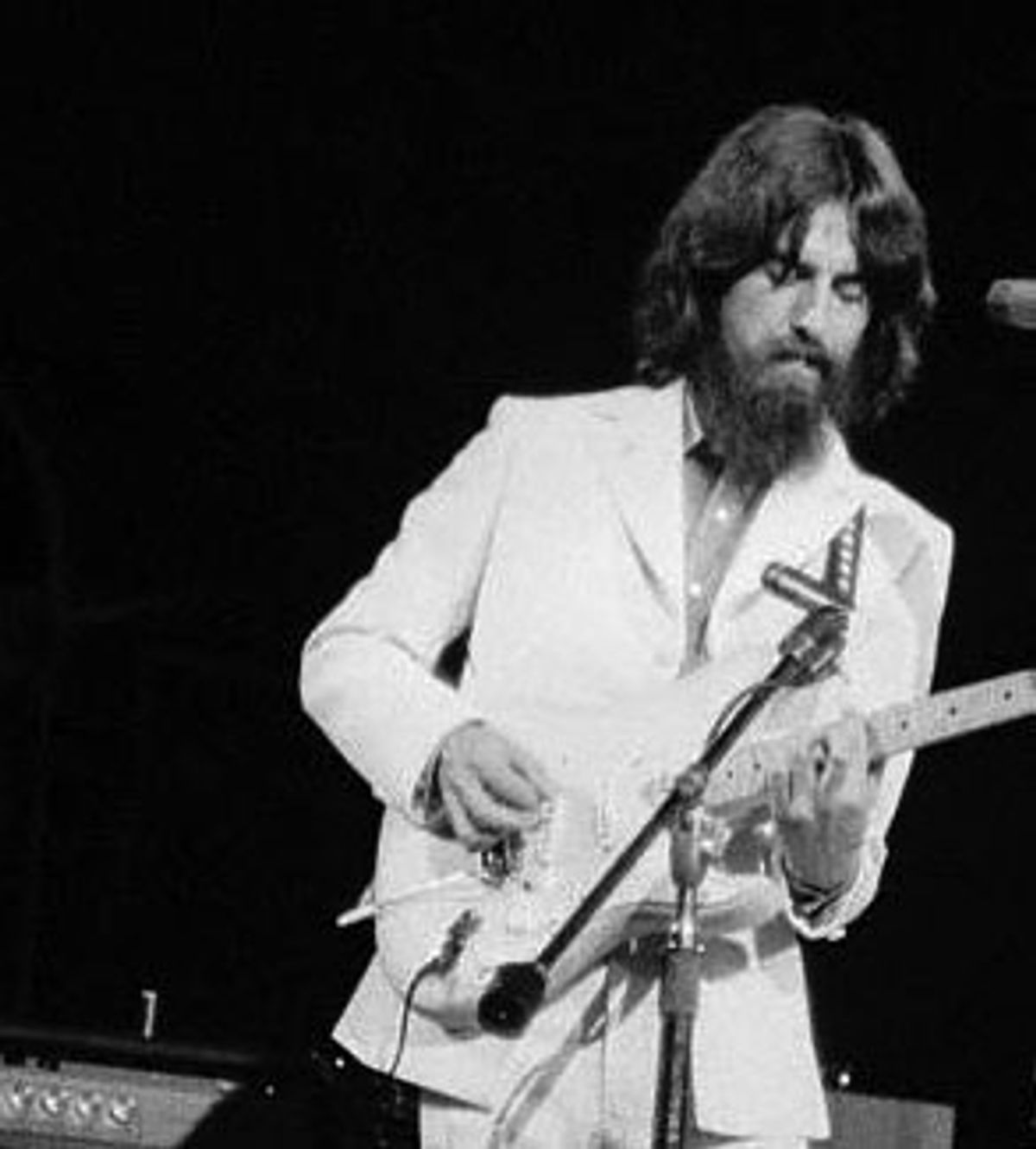

George Harrison organized the Concert for Bangladesh -- the first, and perhaps the greatest, concert-for-a-cause that rock 'n' rollers ever staged. "Rock reaching its manhood," Rolling Stone said in its review. "Under the leadership of George Harrison, a group of rock musicians recognized, in a deliberate, self-conscious, and professional way, that they have responsibilities -- and went about dealing with them seriously."

In a sense, the concert for Bangladesh begins with "Norwegian Wood," where Harrison first experimented with the sounds of the sitar. He went on to India to see Ravi Shankar, the master of the instrument (currently on his own farewell tour). "I felt that his enthusiasm was so real, and I wanted to give as much as I could express," said Shankar in a 1997 interview on VH1. Beatlemania intervened -- people recognized Harrison in Bombay and eventually he had to flee.

But the men stayed friends, and in 1971 Shankar, who had relatives in East Bengal, told Harrison he was trying to put together a benefit show "and maybe raise $20,000, $25,000, $30,000, and send it," Shankar told VH1. "George saw how unhappy I was, and he said, 'That's nothing, let's do something big.' And immediately he, like magic, phoned up, fixed Madison Square Garden and all his friends, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, and it was magic really. And he wrote that song also,' Bangladesh.' So overnight that name became known all over the world, you know."

It's hard now, 30 years later, to imagine rock stars as real honest-to-God consciences of anything. We're used to a certain smug self-satisfaction behind almost every gesture -- and used to the mediocre music that usually accompanies feed-the-world extravaganzas. But George Harrison clearly didn't need to buff his image by raising money for Bangladesh. And this was not precisely a safe cause: America was sending both money and arms to the Pakistanis. Harrison told VH1 that he'd been inspired by John Lennon -- "I think one of the things that I developed, just by being in the Beatles, was being bold. And I think John had a lot to do with that, you know, cause John Lennon, if he felt something strongly, he just did it. I picked up a lot of that by being a friend of John's."

The concert, Harrison added, ran on "pure adrenaline," without a full rehearsal. Who needs to rehearse, however, when you have George to sing "Here Comes the Sun," "My Sweet Lord" and "Something"; Ringo to sing "It Don't Come Easy;" and Dylan to add "Just Like a Woman." And everyone, all together, on the title track:

My friend came to me

With sadness in his eyes,

He told me that he wanted help

Before his country died.

Although I couldn't feel the pain

I knew I'd have to try

Now I'm asking all of you

To help us save some lives

Here we remember the Concert for Bangladesh as the birth of a new kind of political-artistic-philanthropic circus, one of those cases where the first example was also probably the best. There are moments now when one wishes that it had never occurred to singers that they should also preach.

But 1971 was not one of those moments. Not here, where in the midst of a dozen other crises the atrocities in Bangladesh were passing largely unnoticed. And certainly not in Bangladesh, where desperate people screwed by the imperatives of Cold War politics suddenly found themselves being heard by the world. "You can't imagine what a ray of light that was when we found out," said the museum's director.

That small museum in Dhaka is one of the most moving places I know on earth. It is haunted by the usual ghosts -- the millions of Muslims raped and killed by rampaging Pakistani troops, armed and funded by the grotesqueries of Cold War politics. And haunted now too by a shaggy-haired British musician who knew what he should do and went out and did it.

Shares