Gustavo Iglesias stands on the sandy shores of Caibarien, Cuba, and points out to sea.

"Mira," he says, pointing to a long causeway that seems to lead nowhere. "Hay una isla allá -- con las playas vírgenes. Es muy, muy bonita."

Through a hazy December sun, I can see the outline of the tiny key, Cayo Santa Maria. Thoughts of Ernest Hemingway come to mind. Gregorio Fuentes, a Cuban fisherman who died recently, and who Hemingway fictionalized in "The Old Man and the Sea," used to take Papa out to these keys on the northern coast. They were a respite for them both, a place to fish, to party on the virgin beaches and to get away from the bustle of strangers who -- after Hemingway won the Nobel prize in 1954 -- began to appear regularly at Hemingway's suburban Havana home.

But today, this tiny key would not welcome the likes of Hemingway and Fuentes. The pair, close friends for years, would have to separate. Hemingway could step foot onshore, but Fuentes? He'd have to stay aboard his boat or sail home. The only Cubans allowed on the key are those who are either building hotels or working in them. Everyday Cubans are not allowed. They can't moor their boats nor can they drive the 48-kilometer road that juts out into the Atlantic toward the Florida coast.

It isn't just the $5 toll, the equivalent of a month's salary, that keeps them away. It's also the law. Cubans and tourists are allowed to mix when tourists initiate contact or in public areas, but otherwise, never the twain shall meet. "Tourism apartheid," as its critics call it, is taking hold.

The policy isn't actually new. It's been around for at least a decade, since Cuba started expanding its tourism industry to make up for lost economic aid from the Soviet Union. But every year, another beach, key, resort or historic hotel is cordoned off for foreigners. Because the Cuban government's hunger for tourists and their dollars is insatiable -- more than 22,000 hotel rooms have been added since 1990 -- Cuba is progressively being taken away from its own people. Unless something changes, more and more of the country's most beautiful places will soon be off limits to the people who built or founded them.

Many Cubans, if not most, don't seem to notice the irony of this situation. Iglesias, for example, knew I would never rat out his opinions; he's the second cousin of my Cuban-American girlfriend, Diana, and we shared a comfortable rapport. But he only shrugged when I prodded him about his feelings on Cuba's economic policies. Castro's form of tourism, which flies in the face of both socialist and free-market ideals, didn't seem to bother him. Like many other Cubans Diana and I spoke to over the course of two weeks, he simply accepted the policy as inevitable.

This is apparently quite common. "There's a certain habit of resignation in Cuba," says Manny Hidalgo, the Washington office director of the Cuban Committee for Democracy, a moderate Cuban-American nonprofit. "They've just resigned themselves to the situation that they're in."

And yet, however stoic Cubans may be, in a handful of situations I saw signs of the system breaking down. Diana and I played pool at a hotel in Varadero with two drunk young Cubans while the hotel manager looked on. We discussed Britney Spears and Marc Anthony with a pair of locals on the city's white-sand beach -- a conversation that tourists in previous years had to take elsewhere. And in Trinidad, "the most beautiful city in Cuba" according to most guidebooks, I watched a group of teenagers resist police efforts to make them leave an open-air tourist bar.

All of which made me wonder: Could Castro's "tourism apartheid" inspire the kind of dissent that would threaten his regime? Might the attempt to court tourism become a catalyst for democratic change?

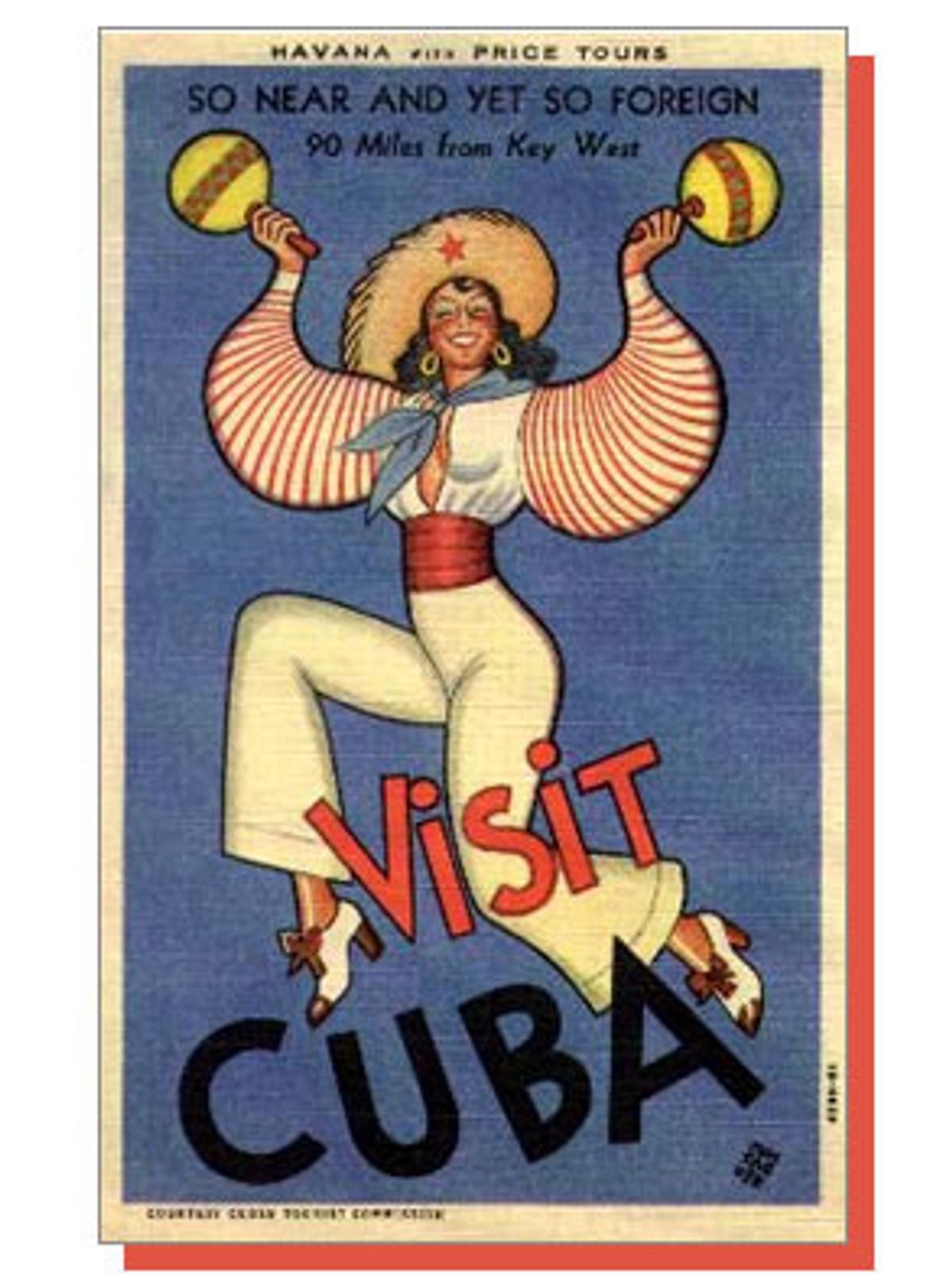

Cuba's beaches and hotels have always been political playthings. Many of the richest 19th century sugar barons lived along the coast, and when tourists flocked to the country in the '40s and '50s, they found that some of the best hotels catered not just to Americans, but also to their Jim Crow brand of racism. Black Cubans could not enter the buildings -- except as servants.

The Cuban revolutionaries, as they agitated and expanded their ranks in the mid-'50s, pledged to end imported racism. They eventually made good on the promise. Soon after Castro, Che Guevara and their comrades seized power from Fulgencio Batista, they seized the private clubs and beaches, then opened them to the public.

Cubans welcomed the change. Nicolas Guillen, the famous mulatto Cuban poet, praised the new level of access. His 1964 poem "Tengo" ("I Have") extols the Revolution for opening up the country to Cubans of African descent. He even specifically uses the beaches as an example, noting that there were no longer prohibitions, only the "giant blue democratic opening: the end, the sea."

Everyday Cubans also enjoyed the sudden property windfall. The Museum of the Revolution -- housed in the former presidential palace and still riddled with bullet holes from the 1959 coup -- holds several pictures of Cubans lounging in front of once-private clubs. The snapshots are simple, yellowed black-and-whites, but they seem to capture the national mood of excitement: Men and women are playing soccer in the sand, families are eating lunch, groups of women are sunbathing or chatting. The beach looks extremely crowded, like New York's Jones Beach in the middle of July.

Throughout the next few decades, open access was the rule. The beaches immediately to Havana's east and elsewhere remained popular with Cubans, and development was limited to health care, agriculture, oil and manufacturing. Tourism was a second thought, if not further down the list of national priorities.

In the '80s, however, Cuba began to build a series of large hotels in Varadero, a town about two hours away from Havana. There were already hotels on the strip of sandy land, some of them famous art deco gems built before the Revolution, but the expansion marked the beginning of Cuba's reemergence as a tourist destination. (A quick Google search for "famous Varadero beaches" yields hundreds of travel agency Web pages.)

The collapse of the Soviet Union severely accelerated the process. The loss of aid and markets for Cuban exports such as sugar forced the economy into a near-depression. Castro called this time "the Special Period" in which Cubans needed to dig deep into their souls to support the Revolution, but with electricity outages, skyrocketing unemployment and other problems, Cuba needed more than socialist resolve.

Tourism came to be seen as an economic savior. Cuba hardly wanted to start courting capitalist visitors who might upset the status quo with their dollars and ideas, but with devastation all around, "What choice did the government have?" says Wayne Smith, a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy who was a Cuba expert at the State Department from 1958 to 1982. "Sugar is shot. They don't have oil to export or any other resource in great supply. They almost had to turn to tourism. It is a contradiction of revolutionary values, but there it is."

Castro, then and now, defends the move by stressing that tourist dollars will be used to help all Cubans. "The government argues, and most Cubans grudgingly hope it's true, that as the economy improves, helped in part by the money brought in by tourism, that the injustices can be ironed out and everyone can have an equal shot at things," Smith says.

But the policies of tourism apartheid, now more than a decade old, seem to be undermining Cubans' faith in Castro's promise.

Many of the Cubans I met expressed frustration with the way police broke up conversations with tourists. A handful of these dissenters were simply Jineteros looking for more freedom to sell me cigars, or get a gift out of me. But others seemed genuinely disappointed, if not angry, about their inability to travel where they wanted and speak to whom they pleased.

Some chose to simply break the policy when police were absent, a practice especially common in Havana. Others overtly resisted the segregation. The group of teenagers in Trinidad, for example, refused to move from a table at an outside bar, confident perhaps that the cops wouldn't make a scene in front of the 100 European and American visitors.

And at least a few seem to have found creative ways to undermine not just the tourism policy, but also more general Cuban restrictions. Take the woman I met in the Varadero bus station -- I'll call her Maria. Smartly dressed in a navy blue miniskirt suit set, she told us about how she planned to use her Italian boyfriend to buy a house. Cubans aren't allowed to purchase private property, she explained, but foreigners are. And since Maria's sister was a lawyer, she was confident that the plan would come off without a hitch. She already had money saved. The fact that her boyfriend came to Cuba for only a few months a year seemed to be nothing more than an irrelevant footnote.

Of course, these anecdotes do not an opposition movement make. For every Cuban who expressed opposition, there were at least a dozen more who seemed perfectly happy to remain outside the tourist clubs and beaches. Many were happy just being within earshot of a band, picking up enough of a beat to justify a hearty dance.

Acceptance is the norm in Cuba, some argue. Tourism apartheid is not "an issue that will cause an upheaval," Smith says. The segregation may be visible and important to tourists, he says, but Cubans have other concerns. "Resentments over tourism would recede quickly if the government would but move ahead with other reforms, such as a small-business law and giving more land for private cultivation," he says.

Yet, perhaps Cubans will once again surprise the experts and the world, as they did in 1959. The tourism policy, unlike other Cuban forms of repression, strikes at the heart of both the Revolution and the Cuban psyche, says Max Castro at the University of Miami. "It's self-discrimination," he says. "That creates a different psychological response in the population. It's a point of stronger frustration -- especially for a people that are as nationalistic as Cubans. It's a real hard pill to swallow for a lot of people."

Some sort of showdown may not be inevitable, but it seems to be, at the very least, possible. Cuba's tourism expansion continues, even in the midst of a worldwide recession that's sucked the life out of the industry. The tiny, peaceful key off the coast of Caibarien is only one example of many projects being developed. New hotels seem to be everywhere and some of the most beautiful plazas in Havana are being refinished and essentially set aside for tourists. Even in Varadero -- which is already full of luxurious, if boxy and functional, hotels -- new construction is common.

Perhaps more disturbingly, the ironies and hypocrisies continue to add up. History seems to be disappearing. Not only are the coastal islands once frequented by Hemingway being gobbled up by the government, but so too are the shreds of literature that praise open access.

Remember Guillen's poem "Tengo," for example? Well, says Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria, a comparative literature professor at Yale, "Guillen is dead now and so is his poem, which I understand is not allowed to circulate because, indeed, certain hotels, bars, restaurants are not open to Cuban blacks. There is an irony for you."

Shares