Rodney Brooks built his first artificially intelligent machine when he was just 12 years old, in his boyhood home in South Australia. He recalls in his new book, "Flesh and Machines: How Robots Will Change Us," that this homemade computer of his "could play tic-tac-toe flawlessly."

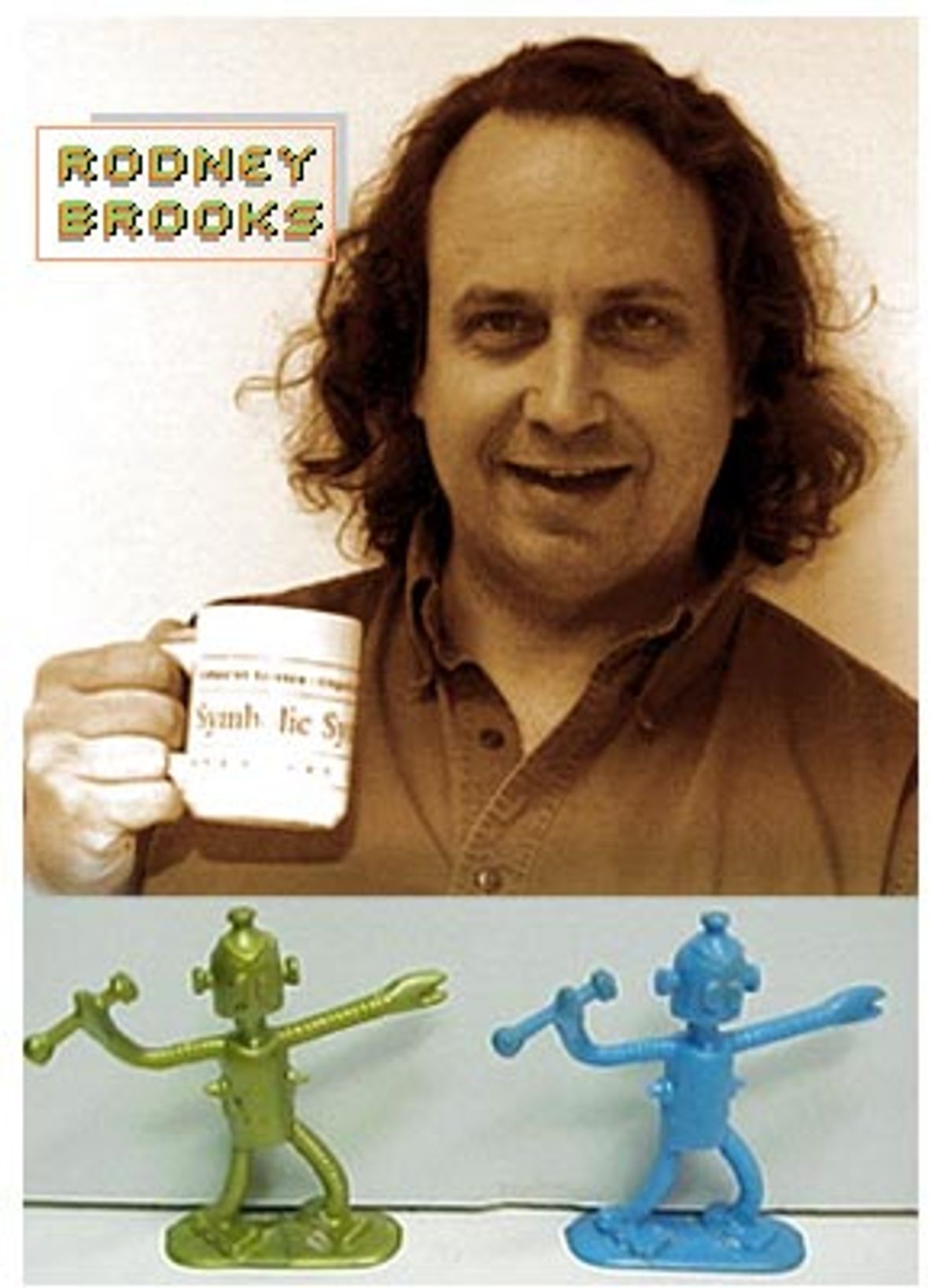

Not surprisingly, as a grown-up, Brooks is now one of the world's leading roboticists. Director of MIT's 230-person Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and founder and chairman of his own robotics company, Brooks has presided over some of the most important developments in the field that fascinates and perhaps frightens everyone who has ever seen "2001: A Space Odyssey." Indeed, among other things, his company iRobot developed the Sojourner technology used to take samples and capture images from Mars in 1997. "The first mobile ambassador from Earth to another planet," he points out, was "a creature constructed of silicon and steel."

It's almost easier to list the academic distinctions and areas of expertise that Brooks doesn't have rather than the other way around. Suffice it to say he's a Ph.D. who did stints at Stanford, Carnegie Mellon and MIT before joining MIT's faculty in 1984. He has been the Cray lecturer at the University of Minnesota, the Mellon lecturer at Dartmouth College, the Hyland lecturer at Hughes, and the Forsythe lecturer at Stanford and on and on.

He has published books and papers on model-based computer vision, robot assembly, autonomous robots, micro-robots, planetary exploration, artificial life and humanoid robots, to name just a few.

Brooks starred as himself in the Errol Morris documentary film, "Fast, Cheap and Out of Control," which was named for one of his own scientific papers. The film, Brooks writes, "featured me and three other misfits (a lion tamer, a topiary gardener and a keeper of naked mole rats)." After a five year gap between filming in 1992 and first seeing the film in 1997, Brooks says he was "appalled" because he saw that he "hadn't had a new idea in five years." Whether this is true or not, he seems to have had one since.

Let's start with a little status report on robot technology.

Artificial intelligence has been pretty successful in hidden applications that we don't notice: from airline reservation systems to voice recognition. We all use some form of AI system everyday, but we don't really think of them that way. Now, the fantasy that we've had about these intelligent humanoid robots that we interact with isn't here yet. But I think of our time as being like 1978 for home computers. There have been robots in factories for some time, but they are now just starting to poke their head into everyday life. We have the robotic toys that we have all seen. Now there's a lawnmower from Friendly Robotics, and Electrolux is selling a domestic housecleaning robot in Sweden. We're going to see more and more of this.

But is there a future for robots beyond serving as gardeners and maids?

Robots are going down oil wells, where they increase yield over man-managed wells by a factor of 2. Some robots, autonomous robots, are being used in the military for bomb disposal and reconnaissance. So we're seeing more of these high-end uses, and they are going to trickle down more and more into everyday life. For instance, we already have certain driver assistance systems in some of our cars. And automakers are planning 2005 and 2006 models that have robotic perception systems that sense the road and sense the driver and can take some corrective driving actions if needed. Those sorts of things are not going to look like robots per se, but they use robotic technology -- in the same way that our cars are now full of microprocessors, but we hardly notice them.

When does artificial intelligence stop being artificial?

You know, we really have this term because it was a way of differentiating us from the machines. But a lot of what goes on in artificial intelligence labs around the world is an attempt to understand human intelligence. So it really is the study of natural intelligence -- and then re-implementation. There's a lot of interaction between AI researchers and neuroscientists, cognitive psychologists and so on. It's a continuum.

What's the best example of machines that can be said to learn?

There are different sorts of learning. In my lab, humanoid robots learn the sorts of things that we subconsciously learn about how to control our bodies -- knowing where our arm is and where our head is. That sort of learning is very common in our robots. Then there's a higher level of learning such as identifying patterns in massive amounts of data. This is not robotics so much as artificial intelligence, but machine learning techniques have made big jumps in the last three or four years and are in use for all sorts of scientific understanding. But there's stuff in the middle: For example, 12 years ago I'd never seen a cellphone, but after I saw a couple of them I could recognize any cell phone. That sort of learning, we're not good at [instilling in robots].

The idea of humanoid robots really captures everybody's fascination. Will they be living among us someday?

In the labs, there's been a big resurgence of interest in building humanoid robots over the last 10 years, especially in Japan but also in Europe and the United States. You may have noticed that a humanoid robot from the Honda Corporation rang the Stock Exchange bell [on Feb. 14]. Now, that was pretty much totally operated to do that. But there has been a lot of work in the labs on building humanlike robots with human emotions, human form and the ability to communicate on a sort of cross-cultural level: Saying "Uh-huh" and nodding, and making eye contact, recognizing facial expressions and processing voices. So certainly that's becoming more and more plausible in the labs. Whether we ultimately decide we want robots with human form wandering around our houses is really an open question. I can't quite decide.

What would the time frame be?

In the short term, they're not going to have that form just because they're too expensive. The robots we have in houses are going to be more tin can sorts of robots. How it all plays out in a 20-year time frame is pretty hard to predict.

I just saw "Westworld" on cable, in which Yul Brynner plays the entertainment park robot, a black-hatted gunslinger, who then turns into a very deadly, real killer. What are the chances that we'll create monsters?

Hollywood has picked up on the idea that there are going to be these robots which are super-intelligent and take things into their own hands. Well, we're not going to build a robot like that from scratch. Over the next 20, 30, 40, years, we're going to build robots incrementally, one after the other, and we're going to decide the things we like having in our robots and things we don't. We're not going to build robots that all of a sudden can be so smart that they can take over the world. We're going to decide when we don't like uppity robots and we'll put controls in them.

What about the other Hollywood scenario in which some fiendish genius builds a kind of Frankenstein robot?

I think that's sort of like somebody building a 747 in his backyard. I don't see it happening.

What do you see happening?

As these technologies become more and more available, we're going to start implanting them in our bodies. So we as humans are going to drift in the robotic direction, as the robots get more intelligent. Where that ultimately leads is a little harder to predict. But it's not going to be something that's going to jump up and surprise us. We'll be making those decisions along the way.

You mentioned the word "emotions" a moment ago. Do you really mean that these machines will be having genuine emotions or even that we will perceive them as such?

That's an interesting question for us philosophically. We as humans have had to deal with some blows to our egos over the last few hundred years. You know, five hundred years ago, we had to give up the notion that the Earth was the center of the universe, and with Darwin, most of us had to give up the idea that we were fundamentally different from animals.

And now?

And now what we're left with is the belief that we're better than machines because we have emotions. You know, when Gary Kasparov was beaten by Deep Blue, he said, "Well, at least it didn't enjoy beating me." I certainly think, as most molecular biologists think, that we are fundamentally machines. We're made out of bio-molecules that interact in a rule-like manner. So if we are emotional machines, then I don't see any reason, in principle, why we can't build silicon and steel machines that have emotions.

Well, will we?

As I mentioned, in our labs we have machines which everyone will agree certainly display emotions and act as if they have emotions. It's going to be a matter of time, as it has been with accepting evolution, before we come to attribute real emotions to these machines.

In fact, you write about the possibility of attributing "free will, respect and ultimately rights" to robots.

I think these are issues that within this century are going to start to come up, yes. What will it take to give personhood to them at some point? What will they have to exhibit to us?

You suggest in your book that we have an unfair bias against machines.

We've seen this same thing throughout human history. In the 19th century, the British and many Americans didn't attribute personhood to people from Africa. Germany declared Jews as non-persons. Of course, robots are different than the examples I just gave, in part because they can't interbreed with us. But it's a similar feeling.

Maybe it will come down to the fact that we have meat for brains and they have circuitry and silicon?

Yes, ultimately I think that will be the only thing left. But I don't think that will even be left because we're going to be putting silicon and steel in our bodies. We're already starting to do that. Tens of thousands of people have artificial cochlea implants with direct connections to their nervous systems that allow them to hear. It's going to happen more and more. You know, I say to my kids: You rebel against me by having a stud put in your tongue, but your kids are going to rebel against you by getting a wireless Internet implant -- and they're going to be instant-messaging their friends while you think they're talking to you. I think that is fairly inevitable. Where exactly that leads is hard to say.

Let's go back for a second because you're saying as much about humans as you are about machines. Is there anything special about human beings -- our consciousness, or what people call our souls?

I'm hypothesizing -- and I think most biologists hypothesize the same thing -- that we are nothing more than bio-molecules interacting. Now, within that organization, there's obviously a specialness to us which gives us consciousness, which a rock doesn't have. But, again, in principle, I don't see at this point why we couldn't build a machine that had those attributes. Whether we are smart enough to build such a machine is another question.

Perhaps we really will be sharing the earth with conscious humanoids

I believe that's where we will end up. But even though a raccoon has good manipulation capabilities, nobody thinks a raccoon is smart enough to build a robot raccoon. And maybe we're just not smart enough to build a robot human. That could be.

Would such robots have the desire to survive and the capability to reproduce themselves?

We certainly don't know how to build such machines, but I don't see why that shouldn't be possible.

On the flip side of things, there's this sci-fi hope out there that human beings will be able to download their minds into machines to live beyond their mortal bodies.

I don't know whether that's going to be possible. It may be that our individual consciousness is so tied up with our own individual brains and development that in the foreseeable future, i.e., the next three or four hundred years, we're not going to be able to do that. That's an unknowable for us.

What problems or challenges are taking up your own brain space these days?

This is not something I am personally working on, but the big open question is in computer vision or robot vision. Over the last few years, our vision systems have gotten really good at tracking moving objects, recognizing faces and recognizing human bodies. But they are still quite lousy at things that a 2-year-old can do: tell whether someone is old or young, tell whether that's a cup in front of them or a tape dispenser or a telephone. They just can't do those things. And we've been trying to [teach robots to] do them for 40 years. So, I'm looking for two or three young Einsteins to come along and figure out what needs to be done there. Because I think we just haven't got it.

While that search is on, what are you doing?

You know, people have been asking me for a long time these questions about whether robots can really have emotions, what's really lifelike and what's living. And so I'm interested in a more fundamental question: What's the difference between living matter and non-living matter -- way down at even the bacterial level? What are the organizational patterns that make something alive? My hypothesis is that there's some deep scientific understanding that we haven't yet hit upon. That's what I've been working on over the last year or so.

Essentially: "What is life?"

Yes, what is life? Now, I recognize that one or two people have worried about this before. This is not a new question. But I hope we're coming at it from a few new angles. I have a research group devoted to this and this is what I'm working on. I think that until you actually do something you don't know how close you are.

Needless to say, there are a lot of people who already have their answer, namely God.

Of course a lot of people will think that, but as an atheist I am convinced there is a material explanation. In earlier times God was responsible for moving the sun across the sky every day, but later we learned that asking how the "sun moved" wasn't even the right question. I expect that there is a similar "answer" to the difference between living and non-living matter.

Shares