"Fortunato!"

No answer still ... There came forth in return only a jingling of the bells. My heart grew sick; it was the dampness of the catacombs that made it so. -- "The Cask of Amontillado," by Edgar Allan Poe

We descended around midnight through a locked manhole near the Jardin de Luxembourg. We wore blue jumpsuits tucked into knee-high rubber boots, and thick gloves, and raggedy utility belts dangling Mag lights and Leatherman hand tools and battery packs that fed lamps atop yellow miner's hats -- not a high Paris fashion, but we looked like sewer workers; the few people on the streets ignored us when we brought out a special key, flipped the manhole up on its hinge and shot into the ground.

The manhole, however, would not close tight, so the grinning loudmouth named Lezard Peint, our leader, peeped out and yelled to a cardiganed grampus passing by. "For purposes of security, Monsieur," Lezard tooted in his splendid professorial French, "would you please jump up and down on this manhole when I shut it?" "What, young man?" the old man grumbled. "We require a push from above to get it closed. For purposes of security, Monsieur." The old man hopped, no doubt looking ridiculous, and the manhole thudded tight, and we could hear him thumping away as we fled into the darkness.

We tramped for a quarter-hour through a 3-foot-wide telecom tunnel lined with red and blue rubber pipes ("Ooh, they are beautiful!" someone exclaimed. "They are so pretty!"), finally arriving at a chiseled rabbit hole by the dirty floor. Waist 33 inches maximum. I went in prone, feet first, backed myself under the blue pipes, and for a fleeting moment I was afraid, the same way children are afraid of basements, of the Thing that lurks. Then I dropped out the other side, 10 feet down, into the catacombs of Paris.

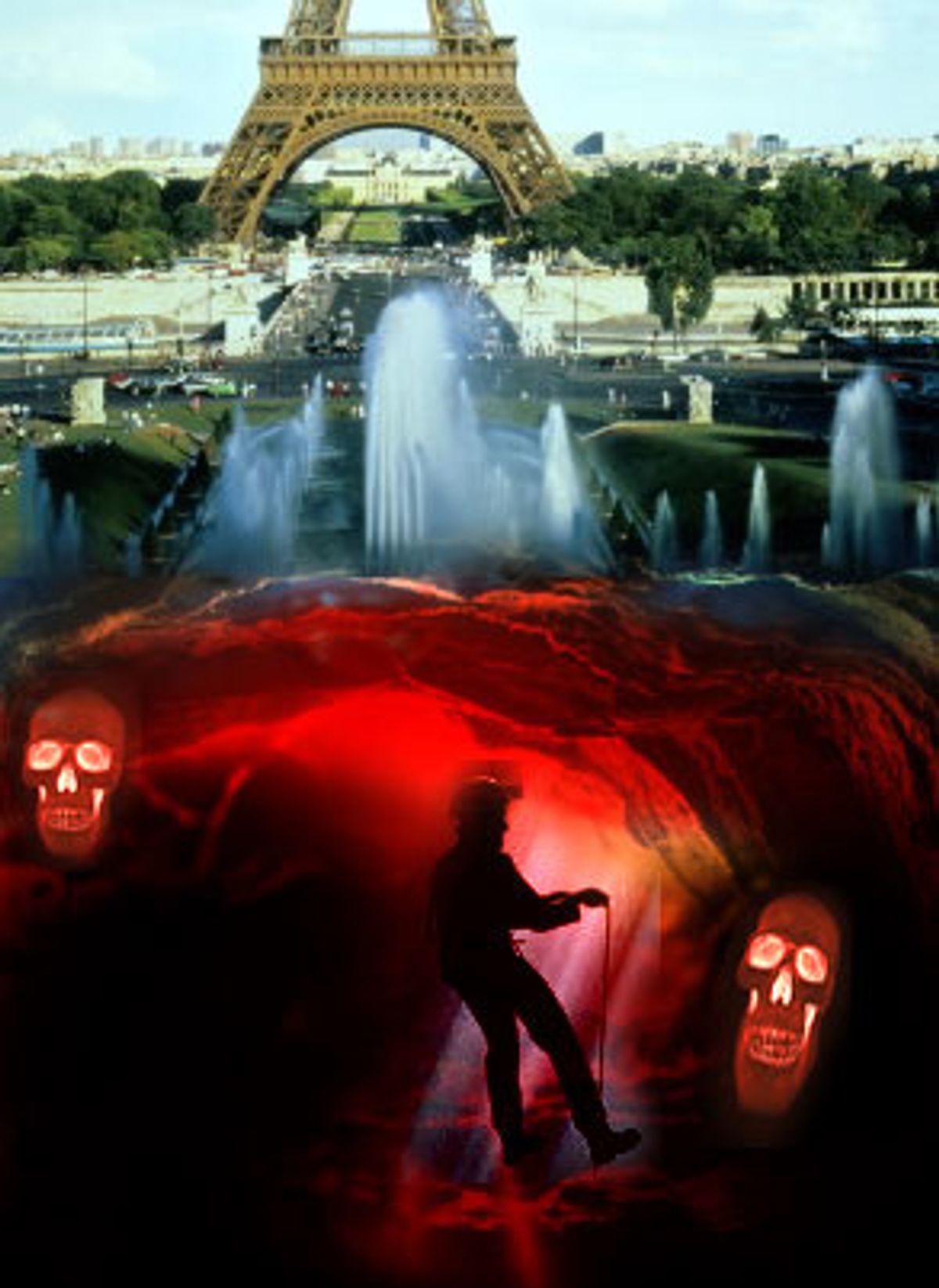

We walked for miles: through foot-high crawl ways with sandy floors, and wild zigzags in squeezed defiles, and pools of clear, cold shin-high water that shivered in our lights. There was graffiti on the walls from the '80s and '90s, a palimpsest of tags and entreaties ("Lost in the catas! Help!"), and underneath the color were stonecutters' marks from the 1750s, the 1600s. Nearby, somewhere, was the Crossroads of the Dead, a low circular room filled with tens of thousands of rotting ribs, where you must crawl and the bones crackle like squashed waterbugs.

There are 560 miles of abandoned medieval quarry tunnels under greater Paris, the largest network of rock tunnels under any city in the world. The catacombs, as they're known, run at depths of anywhere from 20 to 120 feet, honeycombing the arrondissements of the Left Bank and the suburbs south of the city proper. They can be entered from Metro tunnels, utility systems, church crypts and the basements of homes, hospitals, lycées and universities (there's even an entrance in the deepest reaches of Tour Montparnasse, Paris' one skyscraper).

They are multitiered in places, connected by ladders and stairs and open wells. Some are rough-hewed, vast and echoing, 100 feet wide and 12 feet high, some smooth-walled and narrow as a little girl. The oldest date back 2,000 years, to the first Roman settlers, but the majority are products of the cathedral boom and urban expansion of the late Middle Ages, when demand for the thick limestone deposits along the Seine reached frenzied heights. Around 1785, long after the quarrying had stopped, the skeletonized remains of 6 million dead -- the entire population of the city's foul and overflowing central cemeteries -- were dumped underground, forming the largest mass grave on earth.

You can see portions of this necropolis, legally, at the Musee des Catacombes, on the Left Bank, where a rock-hewed placard welcomes, "Stop! You are entering the Empire of Death!" Thirty-three francs buys a hushed promenade through two miles of human ivory, but in summer the tourists pile up against the bone walls; the skulls get shined from so many interested hands.

I did the museum when I lived in Paris as a student. Now I had come back to visit the illicit underground, the tortuous 500-plus miles of it, "the infernal maze" of "The Phantom of the Opera" and Hugo's Hunchback, the galleries where Robespierre dumped his dead and prostitutes tricked in "Crypts of Passion" and anti-Vichy partisans fled SS troopers. Partisans of a sort still haunt the catacombs, young, well-educated, middle-class men who descend by the score weekly and often nightly to explore and throw parties and play cat-and-mouse with the "cata-cops" who patrol looking for them. They call themselves "cataphiles," which means, literally, "lover of the underground."

We settled down in a rocky alcove, a 13th century quarry, and poked candles into the soft, wet walls, which steamed from our human heat. We cooked canned beans and sausage, drank wine, lolled in the sandy earth, and Lezard Peint, who claims to have walked some 9,000 miles in the underground, explained the culture of cataphilia. "There's something that touches you deeply, sensually and psychologically, when you go below, when you are alone with the stone," he told me. Peint bears an uncanny resemblance to the actor Ed Harris, same high cheekbones and grin and same shaven widow's peak on his dome. Like all cataphiles, he goes by his cave-handle, his catanym: Lezard Peint translates as "the Painted Lizard," which makes me think, rightly in his case, of the chameleon. For the Lizard, whose real name is Eric Valleye (32 years old, Web site designer), is known as a master of subterfuge, one of the nastiest pranksters in the underworld.

"Christopher, watch out with Peint," one cata-girl had counseled. "He is feared by many. Sometimes he steals people's lights and maps and backpacks, and then you must find your way out in the dark. Fortunately, you don't stay lost for long, someone else usually comes along. Still ... he once forced a friend of mine to walk out of the catacombs naked.

"And everyone knows," she added, "that he has fascist/Nazi convictions."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

When I first met Peint in a cafe on the Left Bank, I confronted him with these stories, which amused him to no end, hearing his own legend recounted. He smiled broadly, showing clean, white, handsome teeth, which is remarkable among Frenchmen, and rather odd for this particular Frenchman, because the Lizard does not live what would be considered a healthy life. For starters, he never sees the sun. Sunlight, he says, makes him sleepy and weak, and he plans his life accordingly, turning in at dawn and waking at dusk, freelancing from his home. (Generally, he refused to meet or interview before midnight; "I'm still digesting breakfast," he'd tell me around 9 p.m. Breakfast is often something like cassoulet -- franks and beans.) This has been his biological schedule for close to 10 years, so you'd think his bones would have gone brittle from lack of vitamin D, and that he'd be depressed and pale and sickly and rotten-toothed. But no, there he was grinning like the Cheshire cat as I rounded out the litany of his perceived crimes. He shrugged, and sipped his wine.

"The naked guy? I've done that many times," he told me. "Many times! We always make it hard on the neophytes, the amateurs, the newbies. But I did not force these people to do what they did. One time four amateurs stumbled upon myself and a friend. They were complaining about their wet tennis shoes -- innocents, not much courage in them -- and they greeted us in misery, and I said, screamed more like, 'No! We do not talk! Get naked now! It is June 8, the day in the catacombs when we wear only the right sock!'"

And the young men took off their clothes. Just like that. They could've told Peint to go to hell -- Peint wasn't armed, wasn't physically threatening them, it was four against two -- but they didn't. They departed with one sock, a key for home, a candle and two matches.

The rites of passage in the catacombs are no different from the vicious hazing of American fraternity boys. Here's Lezard, say, on a warm night not long ago, dressed in full regalia, an SS lieutenant, looking supremely Aryan with his blue eyes and blond head, surrounded by 10 other "Nazis" in swastika'd armbands (one of them, amusingly, a large black man), singing old German war songs at full throttle, stomping through the tunnels, sieg heiling, the songs echoing down the halls for a half-mile. You hear that and you run. Or you meet them around a corner, accidentally, and they scream, "Was bist du hier? WAS BIST DU HIER?"

"We dress up as Nazis, sure," Peint told me, "but we have no politics, none whatsoever. This is all ... theater. A game of transformations, masks. You see, it's a matter of taking people's expectations, the expectations wrought from fear, and creating an atmosphere so bizarre, so completely out of the norm -- that people do things that would be insane on the surface ... like shedding all their clothing except for the right sock."

It's a theater of cruelty, really. I thought of a home video I'd seen of a kid in the catacombs who was stripped to his underwear and grasping his chest, cold, while a cataphile named Riff, a professional psychiatrist, screamed at him an inch from his face, like a drill sergeant: "Omnamashiva! Say it with feeling!" But the kid produced a weak "omnamashiva." "Nooo! You little ... [Riff shaking his head, disgusted, looking ready to lash out, then, top of his lungs] OMNAMASHIVA!"

"Om-Om-namashi ... va?" The boy trembled, you could see the fear welling in his eyes; he was going to cry. The Painted Lizard filmed the proceedings.

So it was no surprise that when we broke camp, Lezard started lighting firecrackers to ease his boredom. Smoke and echoing blasts, confusion and yowling and laughter and voilà: Gone are Lezard and three of his buddies. Vanished. And I was left with a squirrelly little bespectacled clown named Gadget, who was coughing and half-blinded and tittering maniacally, and a quiet stocky older guy named Christophe, both of whom I'd known for exactly two hours. "Come," said Gadget, in kooky English. He extended a hand. "Come wiz me. I take you. Dead or alive. Come wiz me."

Soon we were very lost. "I'm missing something here," said Christophe, consulting his map. We doubled back, cut right, left, got swamped in some very high water, and about-faced once more.

Gadget was delighted. "This is where it gets good," he said. "This is why we descend. This is when you are like a child again or like a young man and you have just made love."

We stumbled down a tunnel thick with smoke, acrid choking fumes that stung the eyes -- Lezard had been here. Visibility dropped to two feet, blue in our light.

"You guys ever get hurt down here?" I asked. "Anyone ever die?"

"Oh, people open their skulls on the ceilings or they trip and hurt their ankles, but there is only one death we know for certain," replied Gadget, descending a staircase out of the plume. "Philibert Aspairt. Two hundred years ago."

And now, after much turning and twisting, we were passing by Aspairt's white limestone tomb, which was a good sign -- it meant Christophe had got his bearings. The grave is a pilgrimage spot for cataphiles, Aspairt a revered, almost mythical figure; upon the grave a votive candle burns, a fresh lily of the valley sits in a brandy snifter (someone had been here before us). Young Aspairt was a porter, a doorman, at the Val-de-Grace hospital who visited the catacombs on what became a famous mission of theft: He hoped to pilfer the wine caves of the monks of Chartreux. Aspairt disappeared on All Saints' Day in 1793; his body wasn't discovered until 1804. He was found clutching an enormous ring of keys, just a few yards from an exit; the irony was not lost on his discoverers and they buried him where he lay. It is believed that somewhere along the journey Philibert's torch went out. He probably roamed in the darkness for days.

We stood silently at the grave for a moment, then made a short hump to a masoned embrasure pierced by another of those astonishingly small rabbit holes that somehow fit grown men. Then we heard footsteps not our own. Were they behind us? Beyond the wall? The Lizard and his crew shadowing us, playing games? "Shht!" said Gadget.

"Police?"

"Shht!"

"Maybe police," Gadget finally said, and we threw ourselves headfirst into the hole.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The cataphiles are in relentless war, "une guerre souterraine," as Gadget calls it. Head-lamped cave-cops cruise the underground, chasing out trespassers, handing out thousand-franc fines, about $140. Manholes are soldered from above; whole teams descend hauling cement and cinder blocks -- an awful sweaty job -- to block off passages and seal up the rabbit holes. To no avail. Within days, the cataphiles go on the attack, using crowbars, sledgehammers, shovels, hydraulic jacks, high-powered rock drills: smashing the walls, busting the careful solders. One legendary manhole was closed and reopened and closed again 20 times in a week. The police, of course, find this infuriating; the cataphiles think it's hilarious fun.

The most famous of the cata-cops, Gadget tells me, was Jean-Claude Saratte, recently retired, a fat old man with a pug nose and loud voice and truculent style, a speechmaker of arcane poetic flourishes who cataphiles affectionately called "Papa." Saratte and the Lizard had a celebrated rivalry, for Saratte could rarely catch the Lizard, and when he did, the Lizard laughed at him. One night, caught, Lezard stood before a beaming Saratte, who told him, "Fold up your boules, take your pretty lamp and regain the entrance you seem to know so well!" Saratte also made sure to show off the new generation of helmet lamp he was using. "Pretty, eh? You don't have one of these, do you, Lezard?" "Ah," said the Lizard, pulling out the same model, "you mean this?"

Saratte said nothing more, and his band of young officers snickered behind him.

"Saratte was the bon papa, a great man," Gadget tells me. "We threw him a party underground when he retired. Hundreds of people lined up for his signature."

"How'd Saratte get through these tunnels, though, if he was so fat?" I asked Gadget as we squeezed along.

"Eh bien! That was Papa's trick, eh?"

Gadget, 35, whose real name is Bertrand Jannes, is a professional lock-pick, not criminally employed but a legitimate and well-known expert in safecracking. "Having the right key to the right door is everything down here," Gadget tells me. Indeed, the cataphiles literally dream of keys, golden keys that open all doors, and they are constantly committing petty thefts to acquire more of them. They'll hit post offices, construction sites, utility substations, Metro stations, churches. "Go to a psychologist, he'll say, 'Oo la la, you need sex,'" a cataphile named Olrik le Gangster once told me. "No. We just need more keys."

Typically, Peint, Olrik and Gadget might break into the offices of the inspector general of the quarries, the city agency that oversees safety in the catacombs. Or they'll snatch locks off doors, make a mold and replace the lock without anyone knowing. Once they tricked a subway worker, alone at the 1 a.m. closing of the Metro, into believing they were police and lending them his passkey. They thanked him, exited the station and locked the wretch inside. They have keys to some of Paris' greatest monuments -- Notre Dame, l'Opera, le Pantheon -- and passkeys, courtesy of the post office, that open up almost every apartment building across the city.

Which makes for some outré sightseeing: On the first day I went adventuring with the Lizard, we descended into the closed crypt of St. Sulpice cathedral early on a summer night; the Christian Lacroix and Saint Laurent shops were just closing across the street. We entered a wooden double-door into a marble anteroom, and then another door, the air cooling, and then down stairwells and through door after door, and suddenly, magically, a chant arose and around us were shadows of men, shadows on crutches trembling and shadows in pews, bobbing like bouys, and there was a soft distant sound of female sobbing and a woman with her face in her hands. I glimpsed a priest at an altar, hymning, bearded to his chest, but oddly no one remarked us; we passed like ghosts, to an iron grill, Peint flourished a key, and beyond were the chambers where the bones of the saints were rotting yellow.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Gadget and Christophe and I came to yet another rabbit hole, this one 7 feet long, which meant that midway along you were effectively entombed. Gadget was last to come out the other side. You enter with arms extended forward, shoulders squeezed -- and you keep them squeezed, otherwise you will jam up in the passage. Again, there's the undulating and squirming and squiggling and someone has pissed in the hole just to be cruel and the urined soil is an inch from your nose. Now Gadget is emerging covered in filth, the floor drops 3 feet beneath him so his hands are momentarily flapping about like worms and his head hangs over empty space. He makes me think of something being born from an anus. He looks at me, pauses, his head hanging from the hole. "You see, Christopher, you see why this catacomb thing tires me? Ah, but no. Not true. The earth is my mother." He pats the wet stone and drops out like a turd.

But that got me thinking. The average Parisian assigns to the cataphile empire every possible terror and perversion: stories, say, of sex orgies in piled bones or black-massing witches percolate to the surface in isolated bubbles, pop along the airwaves and quickly become hard stone reality. If you believe the fat jolly boulanger, the flower store maman or the fey brunet in the scarf shop, the caves are inhabited by the devil as well.

The media loves these nefarious images, repeats them ad nauseam in the umpteen sensationalist catacomb "exposés" that have aired on French television over the years. "Eighty-five percent of cataphiles have sexual problems," one cataphile told a major network interviewer -- cut to a "dramatic reenactment" of 10 guys fondling a girl with femurs. The punch line, however, gets nixed. "Yes, eighty-five percent!" the cataphile laughed. "That's fifteen percent less than people who don't do the catacombs."

So here's the petite brunet selling silk scarves in a posh shop on the Right Bank, lovely in her red sweater, ignorant that she herself may have "sexual problems" too: "Bring a knife with you. I've heard, well, I've heard that you can get lost and never be found. Ever. A knife and some mace and good luck. I don't know why people go down there."

Why do a hundred thousand tourists line up every year at the Musee des Catacombes? Why do hundreds of thousands more flock to see Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, the stalagmites of Carlsbad Caverns? Caves are homey. This is where man first made his hearth out of the rain.

Or maybe that's pretentious crap. Maybe this delicate Parisienne's fear and trembling consisted of nothing more than that vital difference between girls and boys when it comes to how to approach basements. Because boys everywhere -- and, let's face it, the cataphiles are simply overgrown boys with a very big playground -- adore basements. Girls couldn't care less. The basement is entrance to dungeons and secret doors and hidden byways where Strange Things creep. These Things, if we keep our imaginings lively into young adulthood, can also be found in abandoned buildings, junkyards, empty wharves, rusted factories, those waste places where you trespass on the unknown and get happily dirty doing it, where you'll always find boys bashing out windows, playing hide-and-seek, transforming into heroes and villains of fantasy with the added frisson of the very real possibility that they will get lost, fall down some pit or into a silo, and never be found.

Distantly, we can recall monster myths from the Paris catacombs, like that of the Green Man who stalks and eats vagrants, or that of the Little Devil of the Quarries, who has bleeding eyes and wild hair and like a mole undermines the foundations of buildings, toppling the inhabitants into the earth. I like to think of the Painted Lizard as a modern-day Little Devil -- or an inventor, in his Nazi outfits and psycho-terrorism, of many Little Devils and Green Men thronging the unconscious of the city.

But the cataphiles roll their eyes at this; they don't ponder much on the esoteric meaning of their travels -- if indeed there is any. "The old myth of the cave is that it's a woman's vagina," Olrik le Gangster told me with a yawn. "Frankly, that's --[here he gave a vigorous pumping motion over his crotch]. Look, I go down not to get inside my mom's belly. I go for amusement, to discover my city."

Or as another cataphile put it: "The quarries are testaments of the past that ruthlessly addict us to their strange underground beauty."

So we trek on and on: two dozen winding passages, water spilling over into our boots, feet getting soaked, we've walked at least 15 miles, maybe more. Ahead, I am told, is another hole, one that will take us back to the telecom tunnels and out into night and air, and I'm hungry for it. I'm sick of the catacombs, the growing claustrophobia, the humidity. I want out.

But when I haul up the rear, Christophe and Gadget are tugging at what looks like a thick iron sheet placed over the hole from the other side. Someone has interred us.

"He would do this," Christophe mutters, nodding fatefully. "He would."

"Who?" I ask.

Gadget turns to me, no longer laughing. "Who do you think!!? The bastard himself. Lezard! The bastard!"

Shares