"We predicted it," former Sen. Gary Hart said when I spoke to him the day after Sept. 11. "We said Americans will likely die on American soil, possibly in large numbers -- that's a quote from the fall of 1999." The quote comes from the Phase One Report of the U.S. Commission on National Security for the 21st Century, co-chaired by Hart and former Sen. Warren Rudman, R-N.H. But, before 9/11, no one seemed to much care about their conclusions. During our Sept. 12 conversation, Hart said he was "tearing (his) hair out" in frustration.

He still has criticisms and strong ideas as to how he would handle things differently. "Within a week after 9/11," Hart said Wednesday, "I would have begun a search for a new CIA director ... It's important to say, if you're running a big institution and that institution suffers a serious deficiency, that you will be held accountable. But if nobody is sacrificed for a failure then nobody is accountable." He also has harsh comments about the FBI's anachronistic worldview. "The ghost of J. Edgar Hoover is still in that damn [FBI] building!" Hart says. "They need to clean it out and start all over again."

In 1998, President Bill Clinton, Defense Secretary William Cohen and House Speaker Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., asked Hart and Rudman to serve as co-chairs of the U.S. Commission on National Security for the 21st Century, also known as the Hart-Rudman Commission. Their three-year study and recommendations for a new national focus on combating terrorism and preventing an attack on the homeland, and the creation of a Cabinet-level position for homeland defense, were handed to President George W. Bush in January 2001.

And then ... nothing. Hart met with various members of the administration, including National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, on the Thursday before Sept. 11, to try to convince them that the report should be acted upon and not just serve as a coaster for Vice President Dick Cheney.

"Frankly the White House shut it down," Hart told me on Sept. 12. "The president said, 'Please wait, we're going to turn this over to the vice president. We believe FEMA is competent to coordinate this effort.' And so Congress moved on to other things, like tax cuts and the issue of the day. "

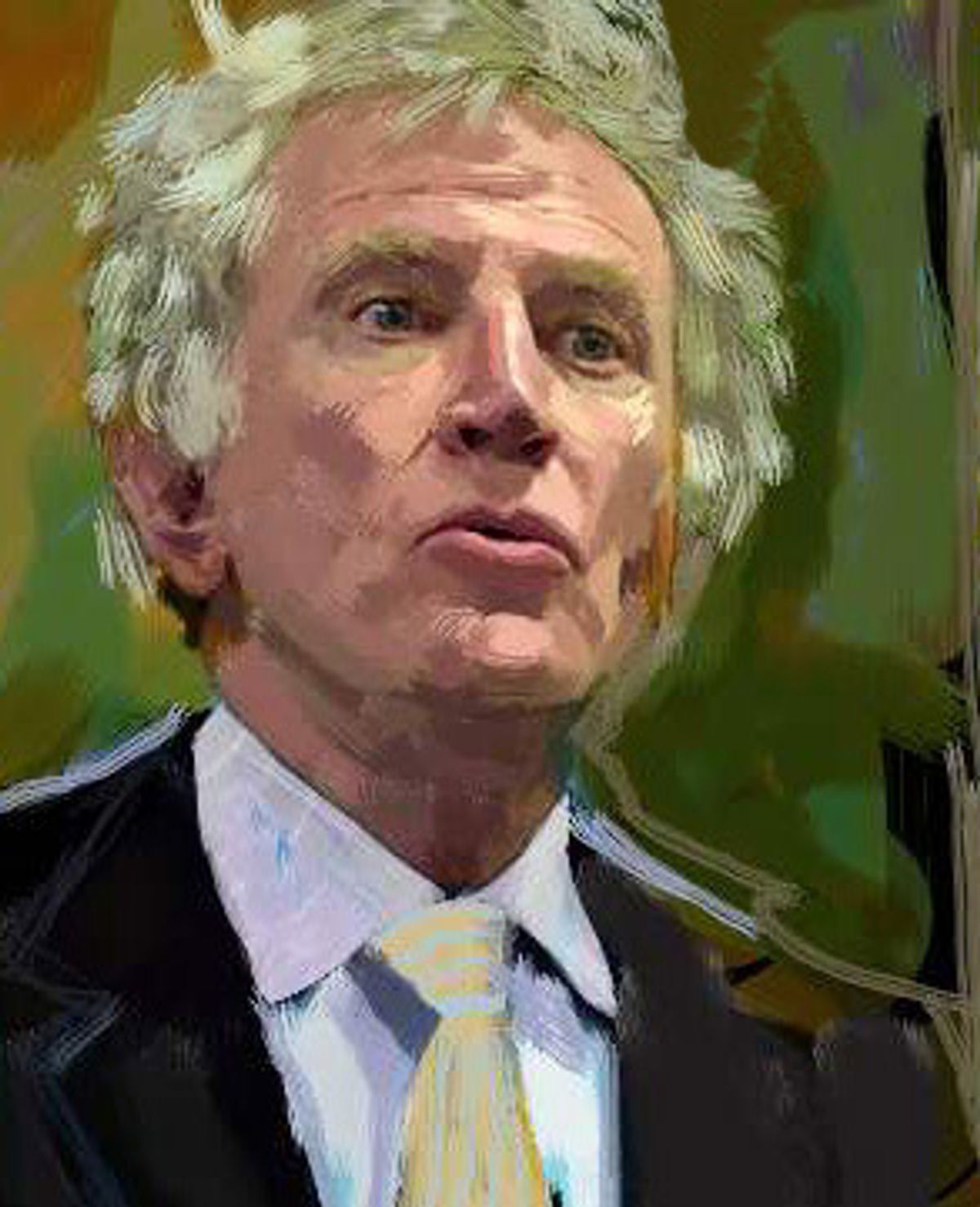

Perhaps no public figure has risen more Phoenix-like from the ashes of Sept. 11 than Hart. Since our interview on that dark and gloomy Wednesday afternoon, he has emerged as a go-to guy for reporters and producers seeking expertise on terrorism. He appeared on "Hardball" this week, and he and Rudman coauthored an Op-Ed in Thursday's New York Times. For a whole new generation of media absorbers, his visage is now a tip-off for a serious discussion about terrorism and the place of the U.S. in the world.

Hart served as campaign manager for the 1972 presidential run of Sen. George McGovern, D-S.D., after which he ran for the U.S. Senate representing Colorado, winning and serving from 1975 until 1987. He unsuccessfully pursued the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 -- losing to Walter Mondale and Mike Dukakis, respectively, both of whom went on to be demolished come November.

In the Senate, Hart was known for seriousness of purpose -- focusing on nuclear arms control, foreign policy, military reform, and information technology, forecasting the demise of the USSR and the end of the Cold War -- and a lack of the hail-fellow-well-met backslapping that endears one to colleagues. Hart may be best known for the tabloid fodder he provided during his latter race for the White House, when photographs -- of him and a young woman named Donna Rice sitting dockside during a Bimini vacation -- emerged and sank his presidential hopes.

After his exit from politics, Hart entered the traditional world of ex-senators: writing books and lecturing, serving on the Council on Foreign Relations, working in international law and business and serving from his home base of Denver as counsel to Coudert Brothers, a multinational law firm. He's also written several nonfiction books and four novels -- including two under a pseudonym: He wanted to see how the books would be reviewed, he says, if his name wasn't attached to them and regular fiction writers -- not political scribes -- were assigned to critique them. ("The reviews were good!" he laughs.)

I caught up with Hart on June 12 -- the nine-month anniversary of our last interview.

After months of insisting that it wasn't necessary, President Bush finally suggested that the homeland security director be made a Cabinet-level position. You and the commission, of course, made that suggestion some time ago only to have it seemingly fall on deaf ears. What are your thoughts about the president's announcement? Do you think, as some liberal critics suggest, that there is something fishy about the timing, coming as it does after a barrage of news of missed signals and dots unconnected?

Well, I think all of us who put in two-and-a-half to three years on the [Hart-Rudman] commission are gratified. It's the right decision. The question of timing is for history to decide; obviously we wish it had been in the spring of 2001. The fact that the president made the decision is a giant step forward. I hope Congress will enact it quickly. I've heard all the arguments as to why it's going to be difficult to do so -- bureaucratic resistance and all that -- but the fact of the matter is it's what's necessary to protect the country.

Some have criticized the president's proposal for a Homeland Security Agency since it doesn't fold the FBI or the CIA into the mix, but keeps them as separate agencies. Do you think that's a mistake? Did your proposal fold them into the new agency?

No, no -- we recommended strong reforms of our intelligence services. But, to a person, we on the commission thought that intelligence collection and analysis should stay separate from acting upon that information, from operations.

Why?

Traditionally in this country -- and certainly in the mid-20th century -- it has been believed that it's important, for objectivity, to have those who collect and analyze not to be attached to those who implement. And I underscore the word "objectivity." You put under one roof those who collect and analyze intelligence with those who are going to use this intelligence and there will be all kinds of conflicts of interest and confusion over rules and missions.

You've been critical of the fact that there haven't been any jobs lost after 9/11. You said on "Hardball" Monday, "We're in an age where no heads roll. No heads have rolled after 9/11. And apparently, we're not living in that era where even people resign out of some kind of duty. So nobody is accountable these days." Who should be held accountable? Who would you fire if you were president?

Within a week after 9/11, I would have begun a search for a new CIA director. Not that there's anything wrong with Mr. [George] Tenet [the current CIA director] but the symbolism is very important -- people have to be held accountable. It's like Voltaire's famous statement [in "Candide"] about how the British hang an admiral on occasion to encourage the others.

It's important to say, if you're running a big institution and that institution suffers a serious deficiency, that you will be held accountable. But if nobody is sacrificed for a failure then nobody is accountable.

What's the risk of no one being held accountable? What happens then?

Just sloppiness, I suppose. The tendency to continue to do things the way they've always been done. If you stay in office after a major failure then there's no real criticism of the way things were being done. And it's very hard for the president to say to the head of the CIA or any other agency, "You failed but I'm not going to replace you -- but I want you to do things differently." You're saying two contrary things. You're saying: "I disapprove of what you did, but I'm also not calling on you to do anything differently." And the symbolism is important, also. That's been the pattern for the last 25 or 30 years, by the way.

You also don't have people accepting responsibility. After Sept. 11, I thought some senior people would have volunteered their resignations. Deputy directors of operations at the CIA, deputy heads at the FBI. Whoever didn't listen to the agents in the field. You'd think they'd tender their resignations. Now whether the resignations are accepted or not is up to the boss. Nobody accepts responsibility anymore. People at the top don't demand it so people in the ranks aren't expected to do it.

Bearing all this in mind, what's your take on Colleen Rowley, the field agent from the Minneapolis office of the FBI who before 9/11 tried in vain to get a search warrant for Zacarias Moussaoui's laptop computer and was rebuffed by Washington FBI officials?

Well that's what I think about it: that nobody was responsible. And it causes a loss of confidence in public institutions. There's no way somebody like me can find out who in the FBI building was responsible for not listening to her. That person -- her boss or her boss's boss -- should step forward and say, "It's my fault." But that just doesn't happen.

On "Hardball" you said that the first secretary of homeland security needs to be "a very strong leader ... because it's going to take some head-cracking to make it work." Is Tom Ridge that man?

I don't know. I don't know Governor Ridge well enough to know. The possible matrix I would use if I were making the selection would be: first of all, experience in Congress, familiarity with the congressional committee system, so you could organize this new agency in a way that responded to congressional concerns and interests. Second, a background in national security matters. And third, a background in intelligence. And you put that matrix together, it's a rather small pool of people: Sam Nunn, Warren Rudman and Lee Hamilton.

You just listed two Democrats and a McCain supporter.

I could find some Bush supporters, I'm sure. Oh, and a fourth element I would add to the matrix: people beyond ambition. People who don't want to run the agency for a year or two and then run for Senate or for governor.

Why do you think that President Bush and Vice President Cheney paid your commission's report so little heed?

You'd have to ask them that. I've never been good at answering questions about other people's motives. The only thing I can offer is deductive reasoning: I guess they thought it wasn't important. They had other issues to focus on.

But you can't on the one hand claim experience -- say that the Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Powell team are an experienced foreign policy team -- and then, on the other hand, claim at the same time, "We were learning our jobs." It doesn't work that way. You can't say you're the most experienced White House team ever and are going to hit the ground running, and then argue that you didn't do anything because you were still hanging pictures in your office.

Many Democrats and those on the left say that if this had occurred during a Gore administration the right would have made sure there was holy hell to pay -- impeachment proceedings and the rest. Do you agree?

Clearly the partisans on the Republican side would have said, "If we'd been in charge this never would have happened." And they would have been critical, sure. They would have said heads should roll -- all the same arguments I'm making, I guess. But I'm not making these comments as a partisan Democrat. I'm making them as someone with experience in this area. Washington is Washington. Everybody would have just been in the opposite role. Democrats would be defending the administration and Republicans would be attacking it.

But do you think Democrats are really aggressively questioning the White House? Lots of folk on the left complain that the Democrats are being pretty wimpy where they should be going after Bush for the various failures we keep reading about in the paper.

It's a matter of taste and style, I suppose. I don't know what you get for that. The American people will make their own judgments about who was asleep at the wheel. I do feel, however, a powerful groundswell for an independent investigation. Not through Congress' various investigative committees, but a genuine effort to determine what went wrong. Not by way of blame allocation, but for history. It's gonna happen, it's gonna happen. It's got to happen. History demands it. We're gonna have to get a clear historical record -- to the degree it's possible to attain it, close to the facts -- as to what happened and why. History will judge whose fault it was. And this is including the end of the Clinton administration -- I'm not saying we start on Jan. 20, 2001. We need to start back whenever we first heard the warnings. When we first heard the words "al-Qaida."

Regarding Clinton, when you and I spoke on Sept. 12, I recall you saying that trying to convince him to take a look at the terrorism issue was like hitting your head against a brick wall.

Well, to be clear about that, that was a much broader issue. I had sent him a letter in late 1994 or early 1995, citing the post-World War II analogy of 1947, 1948. I wrote, "Now we're at the end of the Cold War you should appoint a commission of wise people to give you a new post-Cold War national security policy. Give them a year, give them a staff, give them money. Tell them to tell you here's what you should do differently." And I believe that that would have led to a new focus on terrorism. But from 1994 to 1998 nothing was done.

Then Gingrich got the idea in 1998 to appoint a new national security commission and Clinton responded to that, thinking "We don't want the Republicans or Congress to do this by themselves." We formed [the Hart-Rudman Commission] and then on Sept. 15, 1999, we began making our report known. That was when we wrote that "Americans will likely die on American soil, possibly in large numbers." But it wasn't that I couldn't get Clinton's ear. He read my letter -- he told me he did. It's just that nothing happened for three years.

How long did it take before Tom Ridge met with you and Rudman? I know you requested meetings almost as soon as he was named homeland security director in late September.

Five months.

You were trying to meet with him that whole time?

Yes, though not directly. We were relying on Republican contacts. Warren [Rudman] tried, I think [Newt] Gingrich tried on our behalf, too.

And yet you and Rudman -- the co-chairs of a presidential commission on homeland security -- didn't get to meet with Ridge until March? What was the holdup?

I have no idea. I should say that when we met with him he was extremely cordial, extremely receptive.

The message we were there to deliver was that the administration should get on with setting up a Cabinet-level Homeland Security Agency. And on that, he was noncommittal. He didn't say yay or nay.

Well, obviously, they eventually came around on that. So, what next? What are we not doing now that we need to be doing?

Thinking differently. Adjusting to a new world. And that requires a whole new set of presuppositions and willingness to innovate and create and imagine in our governmental policies and institutions. The agencies are still being run by cold warriors.

Somebody asked me before about [FBI director Robert] Mueller's proposal [to focus the FBI on counter-terrorism]. I said it's only going to work if he does three things. He needs to move to a new unit, get out of the J. Edgar Hoover building. Two, he needs to put a 35-year-old in charge. Three, they need to recruit in the Arab-American community so it's not just white faces trying to penetrate dark-skinned organizations. You need to have Arabic speakers inside. Four, he needs to make a Delta force. If I can think of those things off the top of my head, then surely the really smart people can think of other things.

It's a matter of not being stuck in the past. The ghost of J. Edgar Hoover is still in that damn building! They need to clean it out and start all over again. The 21st century has very little in common with the 20th century. You have to have people who understand that.

Why isn't that kind of thing being done already? It would seem to be common sense.

It's human nature to stick to traditional ways of thinking. It's what holds back political parties, it's what holds back media enterprises, it's what holds back anybody from reform and change. It's just human nature. People get too comfortable to do things other than in the way they've always been done. Machiavelli said the most difficult thing on earth is to reform human institutions. It's because of the inertia. Emerson said the same thing: inertia and the comfort of tradition, and because of the established bureaucracies and power. Nobody wants to give up power. And if you change things, and you hire the 35-year-olds, you may have to cashier a bunch of 55-year-olds. This is not, by the way, an argument across the board for young people. We had a bunch of young people take over Wall Street in the '80s and '90s and they were crazy. They didn't have any appreciation for values. So there's not an automatic merit in youth. But they do have one thing -- a willingness to try something new. But that willingness has got be tempered by some values.

Speaking of young people trying new things, another U.S. citizen was just arrested for conspiring with al-Qaida against the U.S. And Pakistan announced that it has some U.S.-born members of al-Qaida in custody. Does it surprise you when you hear about this?

Not at all. One would suppose it. I think there are al-Qaida cells in the U.S. right now -- though by now they're calling themselves something else. And I think by now have plans and they're searching for a means of carrying out those plans. I think they're in most countries in Europe, certainly in Pakistan. And I think they're in touch with each other. The president was really right about one thing: This is going to take between five and 10 years. And even then we won't know if we've won. These things metastasize.

You know, these are not nation-states. There certainly won't be a day when you see a secretary of state, like Colin Powell, or a defense secretary, like Rumsfeld, sitting on one side of a table and the minister of defense of al-Qaida on the other side, and they sign a piece of paper. We won't know when we beat them.

The issues are clearly complex. We want to have Saudi Arabia as a strategic partner, for example, but then again the strike against the U.S. was financed from Saudi Arabia and something like 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi. Not to mention Mr. Bin Laden. If you were president right now how would you deal with the Saudis?

On the surface pretty much the same way we are now. Underneath, however, I would say "You are going to have to change a lot of things in your country to survive. Keep your religion, keep your social structure, but you are going to have to democratize. And you are going to have to let people know that you're going to democratize. You're going to need to set a timetable for elections, you're going to need to create a parliament -- your princes can run for parliament, or they can serve in the ministries. But you've got to open up your society. Get a competitive press and let the press criticize you. Open up your society. Give women independence and freedom -- and you can do that within your religion."

But you know you've got to walk a fine line between letting any nation and any society keep its traditions and letting it adapt to the world. Though it's in its own interests to do so. It's in our interests, too, but we're also trying to help them preserve themselves so they don't find themselves in chalets in Switzerland overnight. My impression is that the Saudi royal family has jets at the airport all fueled up, money squirreled away, pilots on call, like when the Shah left Iran just before the radicals took over.

We also need a much different energy policy. So I'd also say to them, "We're on a five- to 10-year timetable where we're going to reduce our reliance on your oil and replace it with Russian oil. We want you to know that this is going to be our policy." And yes, that would make them unhappy, because they've got their hooks into us. But they have their hooks into others, like the Chinese.

Would reducing our reliance on foreign oil also include a component of drilling at home, such as in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge? Wouldn't that make sense?

Mathematically, it's not necessary; the oil just isn't there. If you apply different fuel efficiency standards to automobiles and stimulate alternative renewable supplies and all that. All of us who worked on this in the '70s and '80s knew the math on this -- I don't know it anymore. ANWR became a symbol for the Bush administration policy of plundering our own resources at any cost. But we don't need to do it. The Russians have got a lot of oil. And it's gonna be a much more reliable supply than from any nation in the Persian Gulf.

Oil from the Gulf may be cheaper now, but it's subsidized by taxpayers, and by American soldiers. That's a subsidy -- it's a subsidy in human lives. The policy is we as a nation go into dangerous places to get oil and we go to war to protect it. If it gets cut off, our sons and daughters may lose their lives in that war. If politicians said that to the public, I think people may begin to drive different cars. But nobody's said it to them that way. "Drive your SUVs that get 12 miles to a gallon, and by the way it may cost your children's lives." That's exactly our policy right now.

When we spoke Sept. 12, you were also angry at the media for not having paid enough attention to terrorism pre-9/11. You said that a reporter with the New York Times abjectly refused to cover one of your commission's reports. Why do you think the media, before Sept. 11, paid scant attention to these issues?

I don't know. It's funny; reporters ask me that. I have no idea. Well, I do have ideas. Ownership structure, value structures, what sells papers. Why are morning TV programs lifestyle and not hard news the way it used to be? Because some vice president upstairs responsible for corporate profits said, "People want more diet and fashion than they do energy policy." Or terrorism, or whatever. You can see it -- stories are placed differently in newspapers now. What oughta be on the front page is on Page 16, and what oughta be on Page 16 is on the front page. You can do lifestyle stuff, you can do trendy stuff, it's placement and proportion. Lifestyle stuff has almost overwhelmed hard news and information.

I know you had complaints about the press during your presidential run ... when do you think the media started changing along the lines you describe?

Different kinds of people were taking over newspapers and TV. And they began a change in the value structure in the media. Watergate was part of that, it was a shift away from traditional news to personalities. And you sensed that during Watergate that the public was more interested in personalities than they were in policy. Then lots of young people went into journalism to become Woodward and Bernstein, and to become famous for exposé. And the reward system changed. It was more traditional journalism up to the mid-'70s than what it's been afterwards. Then the media structure changed when the Murdochs of the world came in. Families didn't own newspapers anymore. And it affected books, movies -- virtually every part of our society.

Along those lines, I wanted to ask you about comments Sen. McGovern made a few months ago at a reception in his honor in South Dakota. You, his former campaign manager, introduced him and he took a moment -- a poignant moment -- to thank you and sing your praises and tell the world that, yes, you made a mistake in your personal life during your presidential race but it was high time for people to get over it. Was that an emotional moment for you?

I have no response to that.

Well, do you feel any sort of vindication? I mean, in 1988 you were telling the press to pay attention to the more serous issues and the media was more focused on other things, and then 9/11 happens and it's like you were right all along. Do you feel vindicated?

No. Three thousand people died, how can you feel vindicated? Three thousand people who may not have had to have died if a lot of things had been different. If the whole value structure we've been talking about -- what's important, what's not important -- had been different. Why didn't our nation appreciate the threats out there? Why as a country are we so self-absorbed? This is pretty profound stuff, and most politicians are not talking about these issues. This isn't about politicians or the media or the members of our commission -- it's about all of us, about our country. We were growing inward at a time we should have been turning outward. We should have been learning about the world, instead we were focusing on the love lives of movie stars and politicians. It's what I said before about Page 1 vs. Page 16 -- some things are more important than others.

So no, I don't think Warren or I or anyone on that commission ever said, "I told you so." I don't think any of us feel that way. I don't, at any rate. The consequences are just too sad. But where I have become angry is about whether we're learning anything from this. Whether the media is learning anything from it. When the next commission issues a warning, will a New York Times reporter walk out of the room without filing a story? It's Santayana all over again -- he who forgets the past is condemned to repeat it.

I recall your presidential runs in '84 and '88 and you seemed at the time like you were bursting with "new ideas" and optimism and hope about America. And you now seem -- well, I know there's a lot of water under the bridge -- but you seem pessimistic about the U.S.

I'm not getting pessimistic. What you're getting from me is frustration from a lifetime of pushing a rock up a hill. The best book I think I ever wrote was in 1995, it was called "The Good Fight." It was a New York Times "notable book" and it was as autobiographical as anything I've ever written. And in it, I asked: Why is it so hard to change a country that sees itself as progressive and change oriented? And I never really answered the question. It's a struggle I have with my own country. We see ourselves as progressive and change oriented but in fact, over time, when we have opportunities to make change, we inevitably resist change. Why for instance did it take George Bush a year and a half to see what had to be done? What is it that causes us to be so schizophrenic?

So, what you hear from me is frustration. Not pessimism. I'm a very optimistic person. I don't think those 3,000 people had to die. And when you think that way you can't be Pollyannaish, and think everything is always going to work out for the best. It's more of a Keynesian sense -- it will work out. But why does it have to take so long? Why are people so resistant to doing things that to me seem so obvious? Military reform, intelligence reform, this commission, adapting to the information age. Why is it taking so long to reform a political campaign-finance process that is obviously corrupt and broken?

But it's not pessimism. Pessimism is thinking that it's never gonna be different. Frustration is thinking it can be different, but you gotta keep trying to make it so.

Shares