Kris Kristofferson's passport still shows his profession as "writer." It should say "songwriter," this man's consummate cultural skill. True, in the last 20-some years he has also been known as a movie star ("A Star Is Born," 1976); a "flop" ("Heaven's Gate," 1980); a has-been ("Big Top Pee-wee," 1988); and more recently a "serious actor" ("A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries," 1998). Not to mention that Kristofferson has been a cohort of icons such as Janis Joplin and Johnny Cash.

The man is in Manhattan to promote "The Austin Sessions" CD, a fine rerecording of Kristofferson chestnuts like "Me and Bobby McGee" and "Sunday Morning Coming Down" with help from guests such as Jackson Browne and Steve Earle. I will lunch with him at a posh neo-sushi joint in midtown called the Red Eye Saloon. Yes, I know this sounds like a rib joint. But they serve really wonderful spicy sushi, Southwestern style -- as if that dish were a culinary invention of New Mexico.

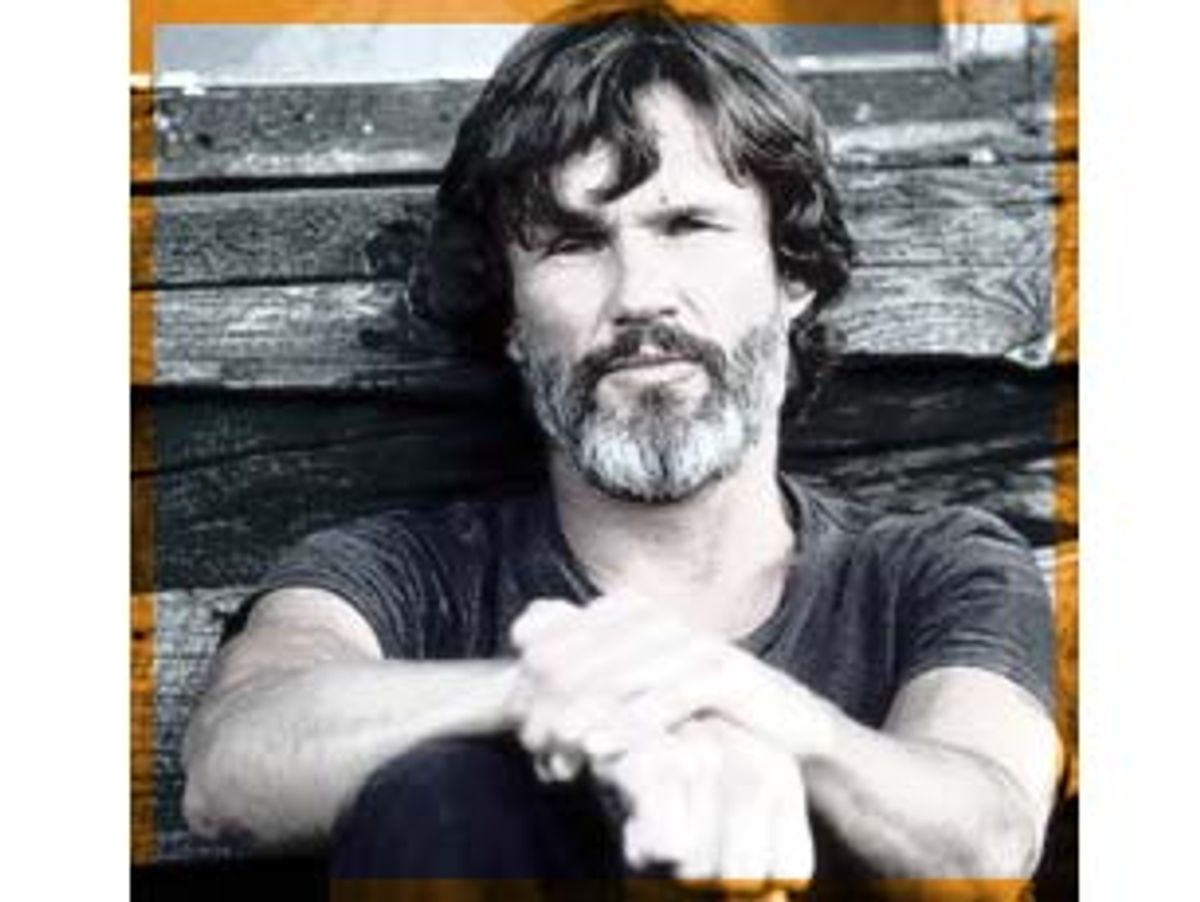

Kristofferson shows up dressed in dark grays and black. His face is craggy but not as craggy as it looks in recent photographs. We're seated at a prominent half-shell booth by some windows. Kristofferson slides in. I follow. I try to keep the proper masculine distance, but then move closer so I can monitor the tape recorder. He seems unfazed by being interviewed. He is neither friendly nor aloof. I break the ice by presenting him with a New York souvenir -- a T-shirt imprinted with a photograph of a handgun and the slogan, "Welcome to New York -- now duck motherfucker!"

I assume this citizen of Hawaii will appreciate the humor. He does. With a quiet laugh he says that one of his kids will love it. Oh shit, I think. Kristofferson's voice is so soft. Will it pick up on tape? I'm aware of a waiter beside me. I absent-mindedly order iced coffee, black. "I'll have the same," Kristofferson says.

"I thought I knew everything there was to know about you," I say to my lunch partner. "But I just saw an A&E special and learned that when you were a Rhodes scholar in England in the late '50s studying William Blake, you were also writing songs."

"The first song I ever wrote, I was 11," he says quietly. "I've been makin' up songs for as long as I remember. I was tryin' to sell 'em in England." Kristofferson occasionally lapses into a drawl, droppin' his g's. "I had a manager over there," he continues. "I answered an ad in the newspaper that said 'Just dial F-A-M-E.' And it was this guy named Paul Lincoln who ran a club in SoHo where rock 'n' rollers used to play."

His voice is so goddamn soft! Suddenly big band music starts playing on the sound system (Benny Goodman or something). I move the tape recorder smack next to Kristofferson's silverware and say a quick prayer to the God of Interview Technology.

"I didn't know anything about the music business or anything," Kristofferson is saying. "I think because I was a Yank at Oxford he thought I would be commercially possible. They got me a record deal with Top Rank records. That's J. Arthur Rank's company -- Rank Movies. Tony Hatch, who later worked with Petula Clark and wrote 'Downtown,' produced the first sessions." The iced coffee comes. He and I both take hits. "We recorded four songs that were never released," Kristofferson continues, his voice a little louder. "An article came out in Time magazine talking about this Rhodes scholar singer ... I had signed a contract with a guy back in Los Angeles before I went to England. I never thought anything about it because nothin' had ever happened, but the man [in L.A.] read about me and threatened to sue. So Rank never released the record."

The conversation pauses while he scans the menu. Kristofferson is such an icon of the 1970s, I'm thinking. I can't imagine him recording in the late '50s. "You were singing on the records?" I ask.

He looks up. "Yeah. They changed my named to Chris Carson. I have no idea what my life might have been like had the songs been a hit." He gives a soft chuckle. I ask him what the music was like. "I don't know what you'd call it," he answers. "It was more like songs that the Kingston Trio and people were doing then. They were not good. I thought they were at the time, I guess, or I wouldn't have tried to sell 'em. Anyway, the deal fell through and I abandoned musical ambition for a while."

The music inexplicably stops (thank God) as a waiter comes up -- some slender New York hiparoo. He recognizes Kristofferson but is too jaded or cool to be fazed. Kristofferson orders the lobster salad while I have a grilled shrimp quesadilla and a gazpacho. The waiter turns to leave. "Excuse me," Kristofferson says. "I'll have the gazpacho as well."

Ah! Twice now the man has followed my lead in ordering! "I've read you've always been a Hank Williams freak," I say, starting the interview again. "When did you first hear him?"

"Twelve or 13," Kristofferson says. "It was on the Grand Old Opry radio show singin' 'Lovesick Blues.' I bought every 78 he ever made. All the Luke the Drifter songs."

Luke the Drifter was Williams' alter ego, whose songs were usually musical monologues. "Remember 'Oh No, Joe'?" I ask Kristofferson. "The Luke the Drifter number about Joseph Stalin?"

He shakes his head. "Never heard it."

"You must have," I say.

"About Stalin?"

"Yeah. It's this great song that warns Joe he better stop messin' with us Yanks." I begin singing, "Quit braggin' about how your bear can bite cuz you're sittin' on a keg of dynamite/Oh no, Joe ... '"

Kristofferson laughs. "Never heard it."

I tell him that he should check out the new Hank Williams box. "I've been listening to a lot of his radio things lately," Kristofferson tells me. "'The Health and Happiness Hour.'" He then says that when he himself was a janitor at Nashville's Columbia recording studios in the mid-'60s, MGM was in the same studio. Williams' widow Audrey would be there all the time rerecording old Hank Williams cuts. "Adding strings to them and stuff?" I ask.

"Yeah," he answers. "Audrey was always trying to make extra records. It was pretty hopeless."

"Now there is a woman with an eternally horrible voice," I say, then ask if Kristofferson remembers the day Hank died.

"Oh yeah," Kristofferson answers, his voice quite soft again. I look from his face to my tape recorder. "I was in high school in San Mateo [Calif.]. I remember a friend calling me up sayin', 'Your hero just died.' At the time, Hank Williams was a pretty unknown quantity. In high school people wouldn't listen to country music. He was never played on popular radio. He was too strong for the popular salad at the time."

Our soup comes. We sip our separate bowls. It's good. "When you took a girl out on a date, what did you listen to?" I ask.

He thinks. "Josh White. Folk music. I remember having a lot of Josh White albums. Johnny Cash. Elvis. I loved the Coasters." I ask him when Dylan showed up on his cultural radar. "I was in the army. I loved him. I read on the back of one of his albums where he said something about Hank Williams being as important as Norman Mailer. At the time country music was still fightin' for respectability and I thought that was a great thing to say."

He sips some soup, then tells me about the time he was a janitor during Dylan's "Blonde on Blonde" Nashville sessions. "I saw Dylan sitting out in the studio at the piano, writing all night long by himself. Dark glasses on. All the musicians played cards or Ping-Pong while he was out there writing." I ask if Kristofferson actually "heard" Dylan recording any songs. "Oh yeah. I thought he was the greatest thing. Bob Dylan. It was very exciting. I was the only songwriter allowed in the building. They had police around the studio they had so many people trying to get in."

That surprises me. "They always had cops there, or was it because of Dylan?"

"For him," Kristofferson answers. Then he raises his voice. "Bob Dylan was very important."

"Did you get to talk to him?"

"No! The closest I got was [his manager,] Al Grossman. Even to his wife and his son Jesse. I wouldn't have dared talk to him. I'd have been fired." He then adds, "I got to be friends with a lot of my heroes there -- like Lefty Frizzell. George Jones. Johnny Cash."

"You weren't a kid," I remark.

"No. I turned 30 as a janitor," Kristofferson says soberly. "I was thinking at the time that Hank Williams died when he was 29. All my peers were at least 10 years younger than I was. I felt like an old has-been at the time."

"And Dylan was just a kid," I add.

"Oh yeah. But my friends in Nashville were all young. None of them had been in the army. It was an advantage in one way being older, but in other ways you couldn't help but feel over the hill."

We talk about the A&E network biography of Kristofferson, which he liked. I remark, "It seems the first few years you were a star you were really burning it at both ends."

"For more than a couple of years," he says. "When I started, the last job I had was I'd gone from living 50 miles out in the Gulf of Mexico on an oil rig, and living in a condemned building in Nashville. Now all of a sudden I had people coming to my show like Sam Peckinpah and Barbra Streisand. People were offering me jobs as an actor."

"Did you think of yourself as an actor?"

"I didn't even think of myself as a performer. I remember I had an actor friend -- a close friend from college -- Anthony Zerbe. He sent me a telegram before I started my first movie, 'Cisco Pike.' It said, 'Have a good time. Ignore the camera.' That was the extent of my training."

A bus boy arrives with our food. "Do you have a salsa?" I ask him.

"We don't have salsa," is the answer. "Tabasco?"

"No thanks," I say. "Damn." Kristofferson and I now both behave like hungry male mammals. We eat our food in silence. If one of us were a woman, perhaps the other would be more circumspect about chowing down, but instead we eat in silence for a good long time. My Nipponese quesadilla is excellent -- perhaps it was Pancho Villa who invented sushi! It doesn't dawn on me to ask Kristofferson how his lobster salad is. Instead, I pause in my eating and take issue with one of the man's most famous words of wisdom: "You're famous for the advice, 'Never sleep with anyone crazier than you,'" I say. "But that assumes you're not in the middle of a drought [with] no choice."

Kristofferson smiles. "I also said that you'll break that rule and regret it."

"Was Janis Joplin crazier than you?" I ask.

He thinks a moment and says, "No."

"Women started throwing themselves at you almost immediately, didn't they?" I don't wait for an answer. "It seems like your life was ... good."

"It was wonderful," he says and eats more lobster salad. "I was just makin' up for lost time. I had had a pretty orthodox upbringing in the 1950s up until I got into the army. Then I started gettin' kind of crazy. Jesus, when I was makin' films with beautiful actresses -- it was burning it at both ends. It was an exciting time. I was either on the road with my band or making a movie from 1970 until into the 1990s. It hasn't really stopped."

"I have this sense that now you're living like a Gauguin patriarch out in the South Pacific," I say.

Kristofferson laughs. "I love where I live out in Maui. I'm a little more torn now than I used to be. I used to love the road." He eats. I eat. "I've got five new kids now," he continues. "Young kids. It's harder to get away. I really have mixed emotions about going back out on the road."

"I really relate to something on that A&E biography," I tell him. "I haven't spoken to my mother in 25 years. Your mother disowned you when you first went to Nashville, right?"

He smiles. "Yeah. But before she died she was coming backstage and hugging Johnny Cash and things like that. She definitely got used to the fact that I was who I was. But while I was unsuccessful I was disowned. I was told, 'Don't visit any of our relatives. You're a disgrace to us.'"

"Did that only change when you became a success?" I ask.

"Probably to my father," Kristofferson answers in almost a mutter. "My father told me that he would never understand me, but he understood that I had to do what I had to do, because nobody could have stopped him from being a pilot because he loved flying. He was glad I had the guts to stand up for what I wanted to do." Kristofferson pauses. "He was a hard person to please. I doubt that if I hadn't been successful there would have been any reconciliation. But hell, by the time my mother died, she was calling up radio station and giving them hell if they didn't play my songs." Then he adds, "Being disowned was a real blessing at the time. I had a lot of guilt on my shoulders for not living up to what everybody expected me to be. For not being Bill Bradley -- being responsible, going into government, being a senator. And when my mother reacted so strongly to me it was very liberating."

We're both done eating. We look at each other again. Since he brought up politics, I mention his 1990 pro-Sandinista album, "Third World Warrior." "Had you been down to Nicaragua much?"

"I'd been down there half a dozen times. The first time I was down there I got to meet Daniel Ortega and all the members of the Nine Man Directorate. I got to go talk to Eugene Hasenfus, the prisoner, you know, that had been shot down trying to resupply the Contras. Remember?"

"Yes."

"In fact, I was the only American who was talking to him."

"What was he like?"

"He felt very abandoned and betrayed. He was an ex-Marine who thought he was doing something the White House authorized."

"And Reagan just dumped him, right?"

"Dumped him," Kristofferson says. "They didn't even acknowledge that he worked for the Americans. The last day I was down there, the Sandinistas asked me if I would like to go talk to him. I really didn't know what I would have to say to the guy because he was on the other side as far as I was concerned. But then I got to thinkin' that he hadn't been able to talk to anybody. And we were both ex-soldiers. I'd been recruited by the same people he was working for, Air America. They had come through flight school asking for volunteers back in the '60s. I figured but for a couple of changes I could have been in his position, so I went to see him."

Kristofferson pauses as the waiter uses a butter knife to scrape the crumbs off the table. My partner and I both order coffee again, without ice. Kristofferson continues speaking so softly I'm almost leaning on his shoulder to hear him. "He was so pissed off at the government. I thought he could be a voice tellin' what they had done. But all he wanted was to get out. He lived in Michigan or Minnesota or someplace. He wanted to be in the woods with his kids. He just wanted out. But I had talked the night before with Daniel Ortega. Hasenfus was going to get the maximum sentence -- 30 years. So I told Hasenfus this story about a friend of mine, Bobby Neuwirth [Bob Dylan's old sidekick in the mid-'60s]. I was over in London one time at this party and Bobby said, 'If you don't believe there is a God, ask for something impossible. And stand back.' Bobby had been very active in AA ..." As Kristofferson talks, I'm wondering where his story is going.

"The next day, I got a call that my daughter had been hit on a motorcycle back in California and was still unconscious. I flew back [from London] thinking about what Bobby said. And I'm asking for no paralysis and no brain damage. And when I got to the hospital, I walked in and saw her all tied up on this table. In a matter of minutes, one of the doctors said, 'Her foot just moved.' And I told this whole story to Eugene and while I'm telling it, I think, I'm really screwing with him. Because I know what he's going to ask for. He's going to ask that he get out. And they're not going to let him out."

Our coffee comes. I move away from Kristofferson. We both take it black.

"Anyway," Kristofferson continues, his voice a little louder (but not much), "Hasenfus asked me if I would go by and see his wife who was staying at the old American embassy -- which was completely empty except for her. So I did. And I found myself telling the same story -- 'If you ask for something impossible ...' I'm thinking at the same time, I'm dangling this false hope in front of them."

He pauses. "Before I left the country I told this woman in charge of the prisons about the one time I was in Saudi Arabia visiting an American in a Saudi jail who was suffering a nervous breakdown. He was a guy who worked for the company that my father worked for. I said that Hasenfus looked to me to maybe be suffering the same type of thing. 'It would really be a shame if he had a nervous breakdown in your prison,' I said. You see, the Sandinistas prided themselves on their prison reform since they had won the revolution -- people were coming from all over Europe to study their jails." Kristofferson pauses. Here comes the punchline: "Anyway, I left and by the time I got home there was a thing on my answering service. It was a woman who said, 'Thanks for your help. He's out.'"

Ha! I should have seen this coming.

"I tracked him down," Kristofferson continues, "and told him, 'I don't know if this did anything for your faith, but it's done something for mine.' But I never heard from Hasenfus again after that. He didn't become part of the anti-war movement or anything. The CIA got hold of him right away and shut him up."

"But still," I say, "the Lord does work in so-called mysterious ways." Please be picking all this up on tape, I silently pray.

"Mysterious ways," he repeats.

"Do you demonize Ronald Reagan?" I ask.

"Do I 'demonize' him?" Kristofferson asks incredulously.

"I do," I confess.

He thinks a moment and says louder now, "Ronald Reagan to me was just a hood ornament on the Mercedes. He had no creative input. He was just a mouthpiece."

"Who were the evil ones?" I ask.

Kristofferson thinks a moment and says, "Kissinger." Then laughs. "I think all the people who were responsible for our policy down there, like Elliott Abrams. I don't know who everyone was. I don't know who all the people were who killed Kennedy. Who killed Bobby Kennedy. King. Malcolm X. Until government responsibility is accounted for [in] those killings, people are going to be cynical about the government, as they've been since then."

Kristofferson goes on in a surprisingly paranoid vein about assassinations. I'm surprised (but then not really) that he is such a political animal -- this side of his personality is seldom seen publicly. Then the publicist from his record company joins our table to shepherd him into a waiting van. Before he goes, I ask him if he votes (I don't), and he says, "Yeah." I ask if he gave money to Clinton, and he says, "No. I view Clinton a lot like Yeltsin -- guys who are better than the alternative. God knows the other side is worse." He thinks a moment and says, "The thing that is depressing to me is that there really is no 'other side.' There is no 'our side' anymore."

This man in black leaves the table. I immediately rewind the tape and flick the Play button. Kristofferson's voice has been recorded. The Lord works in mysterious ways.

Shares