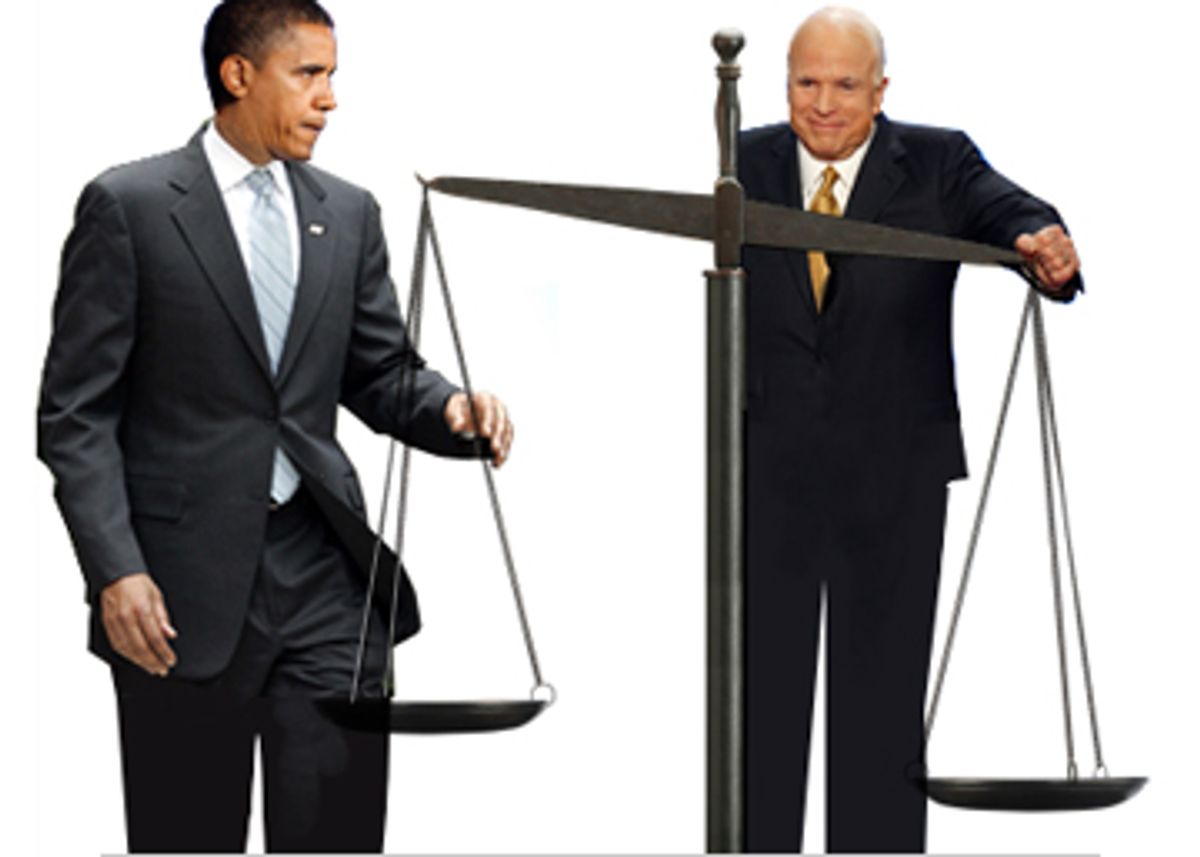

Although a president's longest legacy often resides with his appointments to the Supreme Court, precious little attention has been paid to the issue this campaign season. Yet there is much at stake for the future of the Supreme Court and American constitutional law, and this is one of the areas of clearest difference between John McCain and Barack Obama. McCain has said that he wants to appoint conservative justices like Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justice Samuel Alito. Obama voted against confirmation of both of those individuals and has said that he would pick liberal justices like Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer.

As a result of its current makeup, however, the Supreme Court is likely to tilt only in one direction after this year. Simply put, the November election may well determine whether the court becomes significantly more conservative or its ideological balance remains roughly the same. And a McCain-shaped Supreme Court, pushed farther to the right, could have dramatic and long-lasting consequences for the rights of Americans.

Even if Obama wins the election, it is far less likely that the Supreme Court will become more liberal in the near term. This is because any vacancies on the court between Jan. 20, 2009, and Jan. 20, 2013, are likely to come among the three most liberal justices. John Paul Stevens is 88 years old. Although he is in good health, it seems unlikely that he will still be on the court at age 93 in 2013. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is 75. Perhaps because she is frail in appearance there is always speculation that she might step down. There is a widely circulated rumor that David Souter (now 69) wants to retire and go home to New Hampshire.

Across the ideological divide, the picture is much different. John Roberts turned 54 in January of this year. If he remains on the court until he is 88, like Stevens, he will be chief justice until the year 2042. Neither Clarence Thomas nor Samuel Alito has yet to celebrate a 60th birthday. Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy are 72. The best predictor of a long life span seems to be confirmation for a seat on the Supreme Court. Thus, these five justices likely will be on the Court throughout the next presidential term and perhaps for an additional decade or more.

Thus, a President McCain would most likely replace at least one justice, and possibly more, among Stevens, Ginsburg and Souter -- and given the opportunity he would be sure to do so with individuals who are significantly farther to the ideological right. That would almost certainly leave the court with the fifth vote necessary to overturn Roe v. Wade and allow the government to ban all abortions. (There seems little doubt that Roberts, Scalia, Thomas and Alito would vote to do so.) Moreover, several 5-4 decisions from recent years in which the liberal position prevailed likely would be reconsidered. These could include the decisions preventing criminal punishment of private consensual homosexual behavior; stopping the death penalty for crimes committed by juveniles or for child rape; ensuring the availability of habeas corpus for Guantánamo detainees and others held as so-called enemy combatants; and allowing colleges and universities to consider race to achieve diversity in student admissions.

To be sure, McCain would probably have a tougher time than Obama would in getting his judicial appointees confirmed. There seems little doubt that the Senate will remain in the control of the Democrats in the near term, and there could be as many as 57 or 58 Democratic senators. That majority could prevent McCain from selecting individuals as conservative as Roberts and Alito. Still, the Democrats might find it harder to block a conservative Latino, Asian, African-American or female nominee, just as they failed to block Clarence Thomas' confirmation, despite a Democratic majority in the Senate.

There is always speculation as to whom an incoming president might appoint. Occasionally it is accurate: John Roberts was on everyone's shortlist for a George W. Bush presidency, while Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a common guess for Bill Clinton. But often presidents have picked individuals who were on no one's radar, such as when the first President Bush selected David Souter.

The other problem with such speculation is that it tends to focus on those who are already on federal courts of appeals. This is understandable particularly now, because all nine of the current justices served in that capacity before their nomination to the Supreme Court. But this is only a recent phenomenon. In 1954, when the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, not one of the nine justices had ever served as a judge before being put on the nation's highest court. Most had distinguished careers in public service, including three who had been U.S. senators and one who had been a popular four-term governor of California.

Many legal scholars believe that the next president should look for such experience rather than focusing exclusively on current federal judges. And many believe that there is a real need for a justice who has substantial experience as a trial lawyer or trial judge. Such experience is in very short supply on the current court.

It is not only the future of the Supreme Court that is at stake with the November election. The president also selects judges for the many federal district courts and the 13 federal circuit courts of appeal, the last stop before the Supreme Court. These judges, too, have life tenure and often remain on the bench for decades. Most of the 13 circuit courts of appeal currently have a Republican majority, but on most it is by a small margin. A McCain presidency would likely ensure substantial Republican majorities in every circuit, whereas an Obama presidency would offer the chance to shift some circuits back to control by judges selected by a Democratic president. This balance, too, is important; because the Supreme Court agrees to preside over only a fraction of cases moving through the federal court system each year, the rulings of the circuits often play an important role in shaping federal law.

There are probably many reasons why the future of the Supreme Court has not been a prominent issue this election year: the understandable focus of voters on the financial crisis, the ailing U.S. economy and the protracted war in Iraq, and the sense that swing voters are unlikely to base their selection on the issue of judicial nominations.

But the reality is that Supreme Court justices often serve for decades. (Justice Stevens was appointed by President Gerald Ford in 1975.) The court decides countless basic questions concerning the structure of government and individual rights. Voters may well want to consider that John McCain and Barack Obama offer starkly different choices as to the direction of constitutional law, now and for decades to come.

Shares