Tuesday saw the release of declassified "key judgments" of the latest National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), a consensus analysis by the U.S. Intelligence Community of a given situation on which it is asked to report. Since the beginning of the Bush administration, and the controversial NIE released a few months before the beginning of the war in Iraq, the NIEs have become ever more closely watched. This one, on terrorist threats to the United States, was no different.

The conclusions of this latest NIE were not unexpected, but neither were they uncontroversial, or calming. "Greatly increased worldwide counterterrorism efforts over the past five years have constrained the ability of al-Qa'ida to attack the US Homeland again," the report says, adding that "the group has protected or regenerated key elements of its Homeland attack capability, including ... operational lieutenants, and its top leadership ... As a result, we judge that the United States currently is in a heightened threat environment."

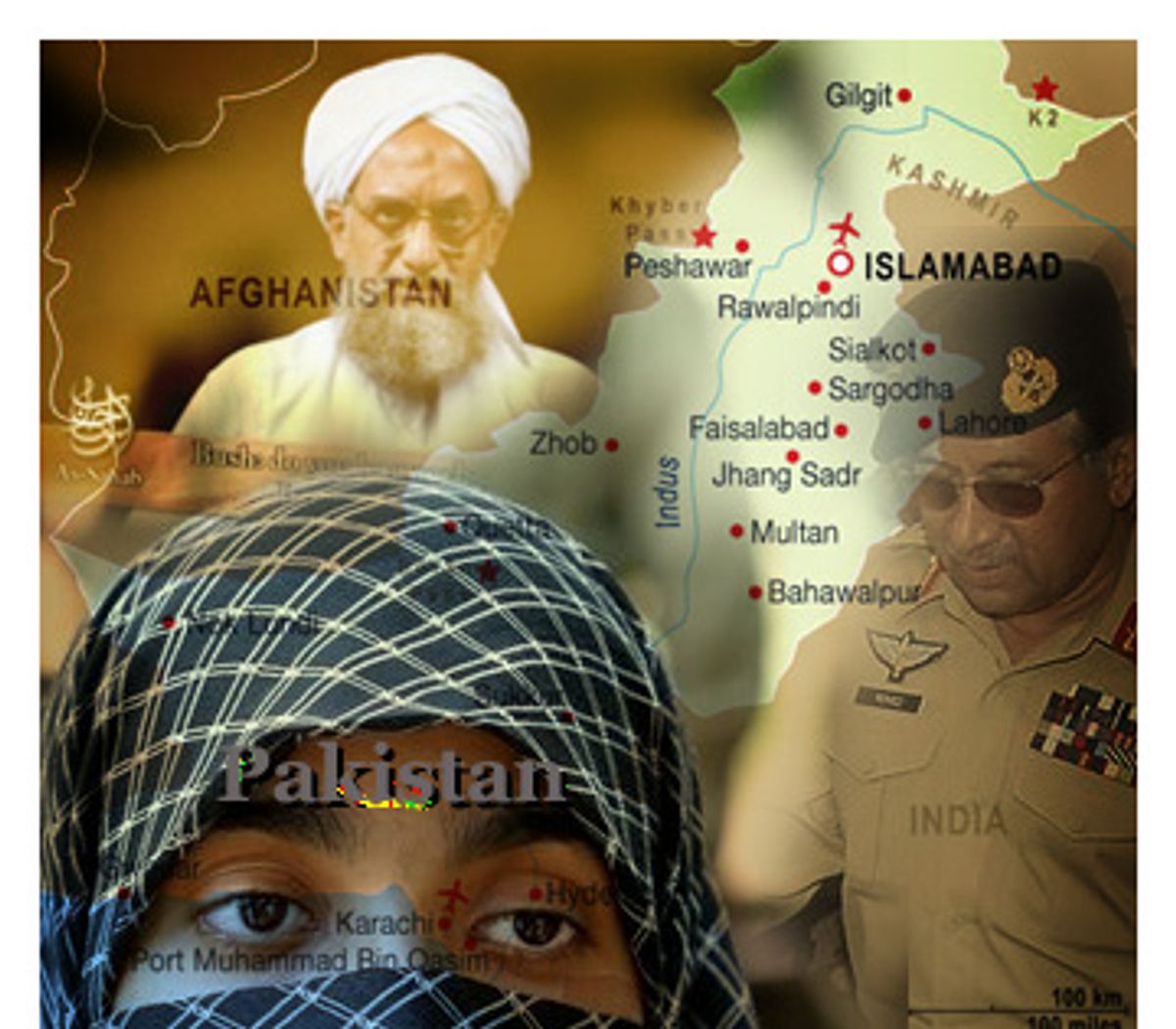

The report has generally been greeted as bad news, an acknowledgment that the war in Iraq has provided opportunities for al-Qaida to bounce back from the blows it took after 9/11. One primary reason given for the bad news is the situation in Pakistan -- the New York Times reportedWednesday that "President Bush's top counterterrorism advisers acknowledged Tuesday that the strategy for fighting Osama bin Laden's leadership of Al Qaeda in Pakistan had failed, as the White House released a grim new intelligence assessment that has forced the administration to consider more aggressive measures inside Pakistan." The situation in that country -- led by a strongman, President Pervez Musharraf, who has been generally cooperative with the United States since 9/11 -- has deteriorated of late. Islamist groups have long opposed Musharraf; tensions boiled over recently in the capital of Islamabad during a siege by government forces of the Red Mosque, which had been occupied by Islamic radicals. The siege ended with the storming of the mosque and the reported death of 102. A 10-month cease-fire between the government and pro-Taliban militants in a tribal region on the border of Afghanistan -- an area the NIE calls a "safe haven" for al-Qaida -- broke down earlier this month.

Former Marine A.B. "Buzzy" Krongard was a businessman who once ran a well-regarded investment bank -- albeit the kind of businessman who punched a great white shark, trained occasionally with a police SWAT team and practiced martial arts -- until 1998, when his friend, then director of Central Intelligence George Tenet, brought him into the CIA to fill a specially created position, counsel to the director. In 2001, Krongard was made executive director of the CIA, becoming the third-highest-ranking official in the agency. He left in 2004, shortly after Porter Goss, a former Republican congressman from Florida, replaced Tenet. Salon spoke with him on Wednesday about the NIE, the situation in Pakistan, and the progress -- or lack thereof -- that the Bush administration has made in the war on terror and in Iraq.

What do you think of what you've heard of the National Intelligence Estimate so far?

It was exactly what was expected.

What do you mean?

No one should have been surprised by the NIE. Were you? I would have been flabbergasted if it had said something else.

Why is that?

Everything that happens that's reported shows that this is the only conclusion you could draw. I mean, have you seen any great improvement in things?

No.

So why would one be surprised?

One of the things that is new in this NIE is the focus on Pakistan as a potential problem area. Do you agree with that assessment?

Yes and no. Pakistan's a very complicated situation. People are getting very critical of Musharraf, but when you look at what he's up against, with the number of people in his military and the number of people in his intel services that do not see things our way or his way, how many assassination attempts has he beaten? He has to stay in power, he has a country very divided, he's bent forward pretty aggressively with us in many ways, and in other ways he's had a hard time. He himself has [never] -- not only he, but no one in Pakistan has ever controlled the [tribal regions near the Afghan border], so we're asking him to do something that's never before been done, with minimal help, while he has a whole lot of other problems. So I'm sympathetic to his situation. On the other hand, there's no doubt that not a lot of good things are being done in that part of the world and something has to be done about it.

What do you think needs to be done about Pakistan?

Ideal, of course, would be for [Musharraf] to invite the U.N. or the U.S. or some group to come in and clean that place out, but that in itself is not going to be very easy. That part of the world, the terrain, the topography, is extremely daunting and very favorable to the people that have lived there and carried on what they do there for a thousand years. It would not be so easy to go in with troops on the ground, which ... we don't even have to spare now. We're all tied up in Afghanistan and Iraq.

What would happen if Musharraf were to fall?

That's easy to answer, because I'd answer it with a question: Who would his successor be? If you tell me that, then I'll tell you what would happen.

The scary thing is, the person is less likely to be as favorably inclined to the United States as he is. So if you got somebody like Iran has ... there's great speculation about the Pakistani nuclear situation, and then you have the Indian tinderbox, and Kashmir -- you've just got all these moving parts. And better the devil you know than the one you don't know. So I don't think it would be in our interest to have Musharraf fall. You go way, way back -- remember all the people that said no one could be worse than the shah of Iran, no one could be worse, gotta get rid of the shah? Well, we found someone worse, didn't we? The ayatollah. There are people who complained about Batista and they got Castro, so be careful what you wish for.

What about this cease-fire that just fell apart between pro-Taliban groups and the Pakistani government in the border regions near Afghanistan?

To the best of my knowledge it was a "You don't bother us, we don't bother you" thing. I don't know that it was as formalized as you indicate.

OK, but the end of that truce, is that going to have an effect on the Musharraf government or our ability to get at al-Qaida?

It all depends. These things happen independently of what governs more sophisticated nations. At the end of World War II, or even World War I, the United States had all these treaties and everything -- in that part of the world, it really doesn't matter what the paper says, it's about how the people behave. When it's in their interest to behave in a certain way, they behave that way. When it isn't, they don't.

The part of the NIE released to the public, the key judgments, says that "worldwide counterterrorism efforts over the past five years have constrained the ability of al-Qa'ida to attack the US Homeland again and have led terrorist groups to perceive the Homeland as a harder target to strike than on 9/11." Do you think that's accurate?

I don't know. I only know that since 9/11 we really haven't had anything [in the United States]. Certainly everything we've done has made it hard, but obviously there's a threshold that's been reached -- they can't do it, or they have patience. Who knows why nothing's happened? Obviously we've done some good work in absolutely cutting off some things, but when you have mothers raising children to blow themselves up and people standing in line to become suicide bombers, it's tough to build a net where the mesh is fine enough to catch all these people. So we'll see.

I was thinking about that sentence about "constraining" al-Qaida and making the U.S. harder to hit in the context of what Ron Suskind has said in his book, and in an interview with Salon -- that the U.S. is actually believed to be "indefensible."

"Indefensible," it's a relative thing, in the sense that we have totally open borders, if you look at the illegal immigrants that are here in the country. What did they identify, 12 million or something? Then there's the drugs that come through. And then just look at it mechanically -- you have two seacoasts and then two borders, and neither Mexico or Canada have that tight control, so it's very difficult, if not impossible, to protect our borders. Now, can we protect them from an armed invasion by tanks and troops? Sure. But one or two people slipping in -- and every day people are slipping in, aren't they?

Yeah.

So it's just a matter of relativity.

The administration has recently started invoking 9/11 again when talking about the situation in Iraq. Are there really any connections, based on your experience in the CIA between 1998 and 2004?

I [left] the agency at a time when we were adamant on the subject that there was no institutional connection. Now, does that mean, did somebody from al-Qaida know somebody from Iraq? I'm sure they did. But there was no institutional contact, point one. Point two, who is al-Qaida? I mean, people talk about al-Qaida like it's the New York football Giants, you know? As if it has a certain number of people on the team and they're all identified by height, weight, rank and serial number, all that sort of stuff. Al-Qaida, in my opinion, is an amalgamation, a loose amalgamation of people who share an antipathy to the United States and all Western values. Some of them hate each other, some of them get along, some of them are very, very small splinter groups, but it's not like IBM, with an organizational chart with black lines and chains of command and things like that. That's my opinion. Now, is there someone in this amorphous organization that had some connection to al-Qaida and had some connection with Iraq? I'd say the odds probably say yes, but that's a long way from saying that under Saddam Hussein, the government then in power in Iraq had ongoing sophisticated meaningful dialogue with the hard-core inner-circle leadership of al-Qaida. We never saw anything that showed a linkage there. Period.

What about the group now known as al-Qaida in Iraq [also known as al-Qaida in Mesopotamia] and the original al-Qaida organization led by Osama bin Laden? The NIE says al-Qaida in Iraq is the original group's "most visible and capable affiliate."

Once again, it's a lot easier to look at the denominator than the numerator. The denominator is, as I said, the shared hatred of Western values. The numerator -- some of these people, I mean, look, in all parts of the Middle East, these militants are killing each other, aren't they? So I guess some of them are united by a greater hatred of us than of each other, but when nothing's going on they'll kill each other. So it's hard to make that big jump and get to, you know, a smooth running corporate image of al-Qaida. That's for me. Maybe other people see it differently, and I'd be respectful of that.

Is the war in Iraq making the war on terror harder?

Sure. Because while it rages, you cannot help but upset people by virtue of collateral damage, breaking in to their homes, stuff like that. Then you have the propaganda, still, on the other side, and finally you have the resources that are being used, the military function that could otherwise be used in the war on terror.

In Vietnam, the one lesson we were supposed to have learned is that a guerrilla action cannot be sustained without the support of the indigenous population, so it's a scary thing to me that the indigenous population seems to be supporting, in many parts of the country, the activities of the terrorists. That's where the war on terrorism there will be won or lost, because as I said, without the general population supporting them they just can't exist, and thus far it seems to me that they have the support of at least a certain population meaningful enough to do what they've got to do.

Are you optimistic about the U.S. making progress in Iraq?

Tell me what progress we've made.

I guess you don't think we've made progress over the past four years.

I think the military, when they went into Iraq, the military part of the thing was terrific. They did just a super job. I think strong, big mistakes were made, and it made it very difficult for our governmental authorities and the military to function since then. I just think that the things were foreseeable -- disbanding the army and the Baathist party and things like that. We managed to deal with Nazis after World War II. Big mistakes. We did not improve the life of the Iraqis in the sense of water or electricity, the economy, things like that, and we're paying the price for it now.

If you look at the United States, if you take Harlem or Watts and remember when you have a lot of unemployed young men with no ability to earn enough to put bread on the table for their families, stripped of their pride, and you give them all AK-47s and have the mullahs heat 'em up every Friday, what do you expect is going to happen? We had riots in this country when we didn't adequately adjust to social concerns.

What about outside of Iraq, in Afghanistan and Pakistan and elsewhere? Is the U.S. making progress?

The military operation in Afghanistan was just absolutely textbook-perfect. The cooperation between the agency and the military's special-operations people, in particular, was -- as I said -- just textbook the way it should operate. Again, the military did a terrific job there. But Afghanistan is Afghanistan, and the further you get away from Kabul, the less central government there is, and it's always been that way and it always will be, whether you go back to Kipling and the British experience there, or the Russian experience, I just think you have a different expectation level in Afghanistan, which is very tribal. And look, had al-Qaida not taken refuge in Afghanistan, the United States, I don't think, would have a great interest in what happened there. Now we're there, and things are better there than in Iraq, but how much better I'm not in a position to judge.

Shares