It's about 8 o'clock on Saturday night, and Murphy's Taproom is going nuts with flash bulbs and cheering. The guy dressed as Santa Claus, a Staten Island limo driver named Lou Barrett, is trying to tell me about his new Meetup group, "Reindeer for Ron Paul," but the din of about a hundred soused Paul fans traps the words in his fake white beard. "Santa is Ron Paul's elf," he finally manages to tell me. "We want to give the gift of freedom this year."

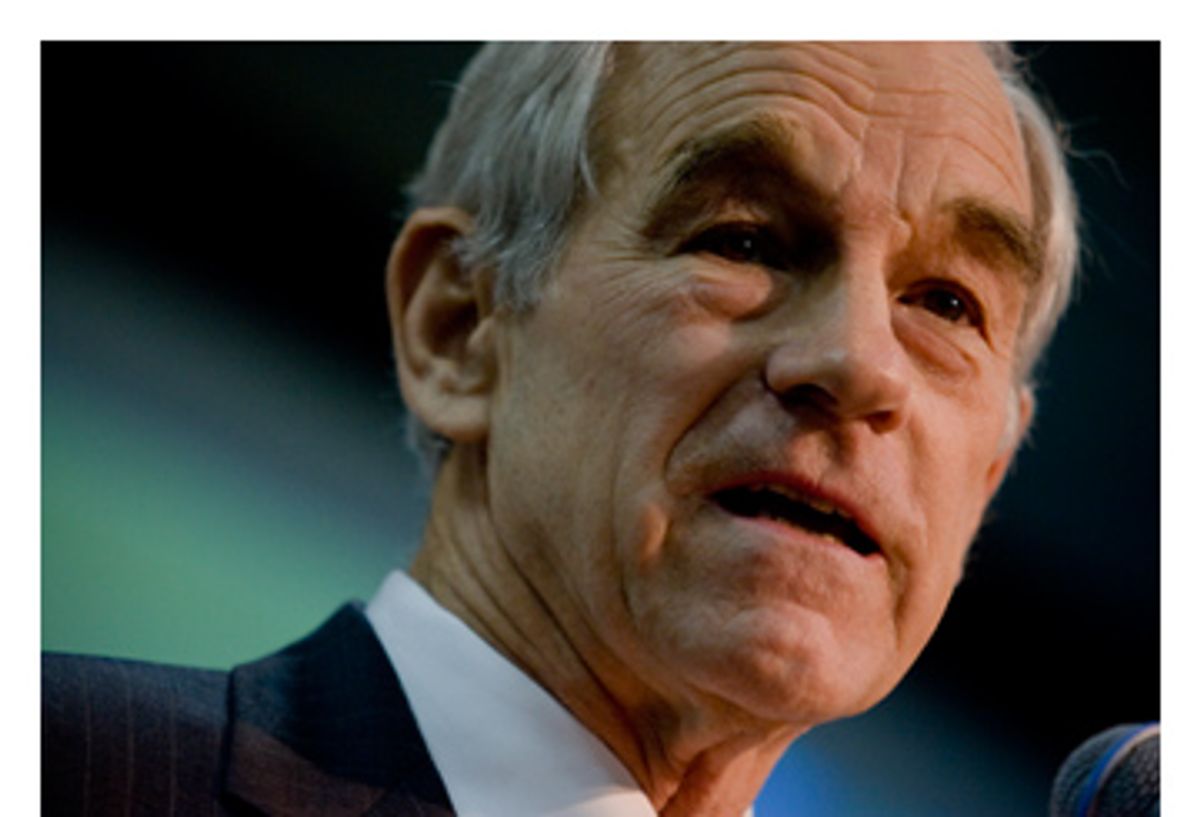

About 10 minutes earlier, Texas Rep. Paul, a lithe 72-year-old obstetrician running a quixotic Republican campaign for president, arrived at the bar with a wide-eyed state policeman in tow. You would have thought Bono had come to Murphy's. Young and old crushed to the door, waved their arms and stood on chairs to get a glimpse of the man. A 21-year-old from Brooklyn, N.Y., Violet Zharov, presented the candidate with a layer cake she had purchased with her own money, inscribed in frosting: "You're our hero. We love you Ron Paul." A former door-to-door frozen meat salesman, Curtis Fenimore, 26, from Wilmington, N.C., began shouting out cheers. "Who you gonna call?" The crowd responded: "Ron Paul!"

Of the mass of supporters, only a handful worked for Paul's nine-person New Hampshire campaign operation. The rest had traveled to Manchester, where the wind chill blows at 3 degrees Fahrenheit, at their own expense, through their own online organizations, determined to canvass the state for the only politician they believe can save the country from tyranny and financial ruin. Some, like Laura and Wesley Lounsburg, of Cane Beds, Ariz., brought their young children and rented a house so they can canvass nonstop through the Jan. 8 primary. Some, like Vijay Boyapati, a former engineer at Google in Washington state, quit their jobs to move here, so they could organize and raise money for the effort. Others, like Matthew Rammelkamp, a 23-year-old from Long Island, N.Y., have just come up for the weekend.

"These are life-and-death real issues," Rammelkamp tells me. He says he is worried about an economic depression, which could begin next year if the dollar continues to fall and the federal government does not deal with the national debt. He says he is worried about government increasingly violating the rights of citizens, especially if there is another terrorist attack. "The government is building FEMA camps," he says. "They want to put chips in our arms." Though he still lives with his parents, he says he has given $2,300 to the Paul campaign, using a credit card that charges no interest for a year. "It's an investment," he explains. "All I got to do is make back a few thousand dollars a year from now."

After circling the room with his security, Paul is again bombarded with chants. "Speech, speech, speech," holler his supporters. The congressman climbs onto a chair, looking giddy. "You have gotten rid of my skepticism. I was a skeptic," he calls out. "You are the campaign. I have joined the revolution." There is a roar.

Just what the Ron Paul revolution entails is a matter of considerable confusion right now among the political chattering class. In Iowa, he is polling at around 5 percent, just a couple points behind Arizona Sen. John McCain and far from the leaders, Mitt Romney and Mike Huckabeee. In New Hampshire, where independents and Democrats can vote in the Republican primary, he polls in the high single digits, with his numbers ticking up in recent weeks. But the early primary states are not likely to catapult Paul into front-runner status. A recent University of New Hampshire poll found that 61 percent of the state's likely Republican primary voters would not consider voting for Paul under any circumstances.

At the same time, the Paul campaign has created something far bigger than just the best canvassing after-parties in the 2008 cycle. His message -- a vocal opposition to the war in Iraq, a strict libertarian interpretation of the Constitution and a wholesale rejection of the nation's economic policies -- have caused tens of thousands to rally to his cause, including many who typically shun the political game. "I never voted before in my life," says Trevor Lyman, 37, a former music promoter who now does independent online fundraising for Paul. "I always thought that the system was working. The war showed me that it wasn't."

A Web site Lyman built raised $4.2 million for Paul from more than 38,000 Americans in a single day, Nov. 5, which was chosen because it was the day Guy Fawkes, a 17th century British revolutionary, had attempted to blow up parliament with gunpowder. Until Saturday night at Murphy's, Lyman had never met Paul, and to this day, Paul has never seen "V for Vendetta," the 2005 cinematic thriller that familiarized Lyman with the Fawkes story. But none of that matters to either Paul or Lyman. For most of this year, Paul has effectively given up control of his campaign effort to his supporters, who organize online, through Meetup groups and Web sites like Operationlivefreeordie.com. At his own volition, Lyman is now organizing another major fundraising day, Dec. 16, a date commemorating the Boston Tea Party in 1773. "I would bet almost anything that we will beat $4.2 million," Lyman tells me at Murphy's. Already, he adds, 23,000 people have pledged to donate on that day.

Such mass mobilization has inspired Paul, a lifelong libertarian who has often been treated in Congress as a dotty old outcast with strange ideas. Throughout his political career he has argued for legalizing gold and silver as legal tender, ending most foreign aid, abolishing the income tax, eliminating the Department of Education, and ending the federal war on drugs, among other things. But it is his constant and outspoken opposition to the war in Iraq and President Bush's expansion of federal powers in the war on terror that has gained him notoriety. His appearance as the antiwar gadfly at recent Republican presidential debates turned him into a sort of counterculture star. "What has happened to me is almost unbelievable," he told a group of college students Saturday morning in Manchester. "The campaign is going much further along than I have ever dreamed."

That progression has prompted Paul to begin hitting the campaign trail in earnest in recent weeks. For most of the year, Paul resisted the traditional candidate role by choosing not to visit early primary states while Congress remained in session. But this weekend brought a flurry of events in New Hampshire; on Saturday, there was a speech in Manchester, a stroll down Main Street in Nashua, a visit to a gun store in Hooksett, and a town hall in Salem attended by about 50. In the course of the day, however, he encountered no more than a few hundred local residents, in part because so many of the people who showed up at his town hall came from out of state.

Amir Hirsch, a resident of Boston, came up to New Hampshire to tell Paul about his plan to produce 15,000 pieces of gilded "liberty dollar chocolates," with Paul's face embossed on the front, a symbol of the need to return gold as legal tender. "I would love to get raided by the feds," Hirsch said. "Because I would eat all the evidence." Tom Moor, a 42-year-old musician from Dedham, Mass., came up to ask Paul if he wanted to come to a rally in his honor at Faneuil Hall in Boston on Dec. 16. There were also three day-traders from Austin, Texas, all in their mid-20s, who had flown up Saturday morning to spend a week canvassing for Paul. "This is the biggest bang for your buck, so to speak," one of the traders, Jared Morris, 26, said of the Granite State.

This extraordinary outpouring of enthusiasm is reminiscent of nothing so much as the early months of Howard Dean's 2004 presidential race, when money streamed in over the Internet and excitement coursed through the Democratic base. But when I sat down to talk to Paul in Nashua, he was less than enthusiastic about the comparison. "Philosophically, I hope we can do a lot better, because not many people identify him with getting the war over with," Paul said of Dean. "I would hope that what we are doing is bringing many people from the left as well as the right together to have an ultimately significant change in foreign policy."

Philosophy is something that Paul speaks of often. It is the driving force in his life and his politics, and he hopes it can become his legacy. "Our country has gone astray," he told me. "There are all kinds of problems. People are hurting. They want something new. The philosophy comes along. We offer this. And it's a potential solution." But when you talk to his most die-hard supporters, the ones who have traveled north at their own expense, it's difficult to attach their motivations to any single theory of government. They tend to worry about encroachments on their liberties. They oppose the Iraq war. They harbor concerns about an Orwellian future for the nation, and significant pessimism about the current state of the economy. Many of them talk about how refreshing it is to find a politician who speaks bluntly and forcefully about the importance of personal liberty.

"He's got the brass ones to go where the other ones are afraid to," explains Fenimore, the door-to-door salesman who is leading cheers at Murphy's. To hear him tell it, Fenimore's affection for Paul is rooted in his love for his country as the land of the free. "In elementary school, I fell in love with the idea of America," he says, adding that he is not sure he will be able to afford staying in New Hampshire through January. "I tell people I can't afford to do it, but I can't afford not to do it."

But perhaps the best explanation of the Paul phenomenon came from Rammelkamp, the young man from Long Island who had taken on significant credit card debt for the Paul campaign. He told me that to understand Paul, I had to think of the American people as a baby elephant, chained to a tree. "It realizes that it can only walk 5 feet in each direction. It realizes that it is a slave. When it grows old enough, it is strong enough to break away from the tree. But it doesn't know." He pauses, to let this sink in -- the American people are a captive animal unaware of its own power to claim liberty. "When was the last time you tried it?" he asks me of breaking free. "Maybe you are strong enough."

And so for thousands of his supporters, Paul has begun to symbolize freedom itself. He is the baby elephant who broke his chains, the Guy Fawkes for a new millennium. And with his candidacy, his supporters believe he shows a way out of the morass in Iraq, a way away from the burden of taxation and the fear of economic insecurity, a way to strike back against the creeping power of the federal government and the free-spending culture of Washington. He is a political savior for people who feel trapped by two political parties that have failed to solve the nation's problems, by a political dialogue that often skirts the real issues, and by a federal government that expands its power by marketing fear. Ron Paul, they hope, is the way out. "It's like do or die," says Linda Hannan, a 35-year-old paralegal from Staten Island, N.Y., as the Murphy's celebrations continue. "Liberty and freedom are our future."

Shares