When Mitt Romney tested out what he hopes will be the themes that define his 2012 presidential bid last weekend, much of the press coverage -- here and elsewhere -- focused on the idea that Romney was (once again) trying to reinvent himself. An image of Romney as a spineless opportunist took hold during the 2008 campaign, and here he was playing to type.

I've spent an awful lot of time dwelling on Rommey's transformation from social liberal in Massachusetts to right-wing culture warrior on the national stage -- "an unusually spineless opportunist," is one of the terms I've used to describe him. So I read with interest pieces this week from Brendan Nyhan and Paul Waldman, both of whom believe the press is rapidly turning Romney into, as Nyhan put it, the Al Gore of 2012 -- that is, the victim of reporters who are so invested in a caricature that they manufacture "misleading narratives that reinforce that frame."

They raise some valid points, mainly involving the number of recent news stories that have played up new clothing styles that Romney is sporting. They are right: This seems excessively trivial and selective; every candidate makes strategic decisions about clothing, but Romney is being singled out for it because he's the "inauthentic" one.

But I think they're too willing to downplay the significance of the changes in Romney's public positions and attitudes. For instance, Nyhan suggests that Romney has only done what anyone else in his position would do:

Any politician who succeeds in a hostile state (like Massachusetts for Romney and Tennessee for Gore) has to take moderate positions and make compromises that are relatively unpopular with their own party's base. As a result, the transition to the national stage requires changes in their profile and issue positions. The most skilled politicians who accomplish this feat tend to be seen as slick (like Bill Clinton*), while less skilled ones like Gore and Romney tend to be seen as inauthentic.

While I understand Nyhan's point, I object to the assumption that Romney couldn't have survived without taking the positions he did in Massachusetts. Yes, it is a heavily Democratic state, one with some deeply liberal pockets. But it also has plenty of voters who are opposed to abortion, or profoundly ambivalent on the subject -- many of them blue-collar voters who generally vote Democratic. Take a look at the overwhelmingly Democratic state Legislature and count the number of pro-life representatives: You'll be surprised.

The truth is that we don't know if Romney could have won as a pro-life candidate because he didn't even bother to try. He presumably made a calculation that doing so would risk the support of reform-minded, culturally liberal suburbanites. So he waited until after he was elected governor (and ready to abandon any reelection hopes) to announce his conversion, using a very dubious cover story.

This was a choice, and not every politician in his shoes would make it. Just look at Chris Christie, who won the governorship of a state that's just as hard for a Republican to win as Massachusetts. But when Christie ran in New Jersey in 2009, he was honest with the state's voters about his pro-life views. There were commentators in New Jersey (and nationally) who said this would do him in -- that only a pro-choice Republican (like Christie Whitman or Tom Kean) could win in socially liberal New Jersey. But they were wrong. Christie prevailed by the second-largest margin since 1972 for a Garden State Republican.

I'm certainly willing to acknowledge and accept that politicians will tweak some positions and alter some rhetoric when they move from the statewide level to the national level (or when they move from the local level to the statewide level), and I'm not a stickler for absolute, total consistency. But that doesn't excuse politicians who change virtually every position and overhaul virtually every attitude they've articulated. Some measure of consistency is important -- some way of discerning what issues, what ideas and what values really are sacred to a leader. There is an acceptable middle ground between needless martyrdom and the game Romney plays (abortion is only one of many, many examples). Christie, it seems, gets us closer to the ideal: Sure, if he ever goes national, he'll make some changes -- but nothing like we've seen with Mitt. Like him or not, we know there's an authenticity to Christie's public persona that just isn't there with Romney.

Of course, Waldman wonders if this authenticity even matters:

Finally, when reporters start reporting on Mitt's lack of "authenticity," they ought to tell us why they think authenticity is important to being president.

I think it matters for two reasons. One is practical, and it has to do with the expectations that a party's base has for the leaders it nominates.

Take Mitt Romney and the national GOP. Since abandoning Massachusetts, Romney has taken extraordinary pains to ingratiate himself with the very conservative national GOP base, taking every position that polls well with it and expressing just about every outrage it feels. You might argue that, in a perverse way, the GOP base should be excited by this transparent pandering: If Romney ever gets in the White House, surely the pressure to stay in the base's good graces will force him to pursue the priorities they want him to pursue.

But this is where inauthenticity is a wild card. Here I think back to the recent national politician with whom Romney (I believe) has the most in common: George H.W. Bush. He was just as ambitious to climb and just as eager to please the national GOP base as Romney now is -- and, like Romney, he had to completely reinvent himself. Bush initially ran for president in 1980 as a moderate-to-liberal Republican, a nominally pro-choice tax-cut skeptic who believed government could play an important role in Americans' lives. He lost to Ronald Reagan, realized how fundamentally conservative the party was becoming, and then (after catching a huge break and being placed on the ticket by Reagan) spent eight years as vice president changing his positions, rehearsing new rhetoric, and establishing himself as a New Right true believer. The conversion was as sloppy as Romney's -- especially when Bush told a group of religious conservatives in 1987 that he considered himself, an old Yankee Protestant, a "born-again" Episcopalian.

Still, he pulled it off, surviving the 1988 GOP primaries and winning the general election. But when he was president, he turned his back on the conservative base on several major issues. The most dramatic was the 1990 budget. As a candidate, Bush had attacked his main GOP primary foe, Bob Dole, for "straddling" on taxes, and he had electrified the Republican convention with his "Read my lips: No new taxes!" pledge. But faced with climbing deficits and an impasse with congressional Democrats, Bush caved in the fall of 1990 and signed a tax hike deal anyway. In other words, he betrayed the party base that he'd spent eight years pleading with to consider him a soul mate.

You can argue that Bush paid a stiff political price for doing this, since he was challenged in the 1992 GOP primaries by Pat Buchanan and then lost in the fall to Bill Clinton -- and that this example would dissuade a future Republican president from spurning the base so dramatically. But that logic doesn't quite hold up, since Bush easily survived the Buchanan challenge and -- as late as June of 1992 -- seemed well-positioned to defeat Clinton. He lost because the economy was in rough shape in the fall of '92, not because he raised taxes in the fall of 1990.

The Bush example, then, highlights why a party base should care about authenticity. GOP base voters are right to be suspicious of someone who has changed positions and attitudes as frequently as Romney: In a pressure situation like the one Bush faced in the fall of '90, will he really stick to his conservative guns?

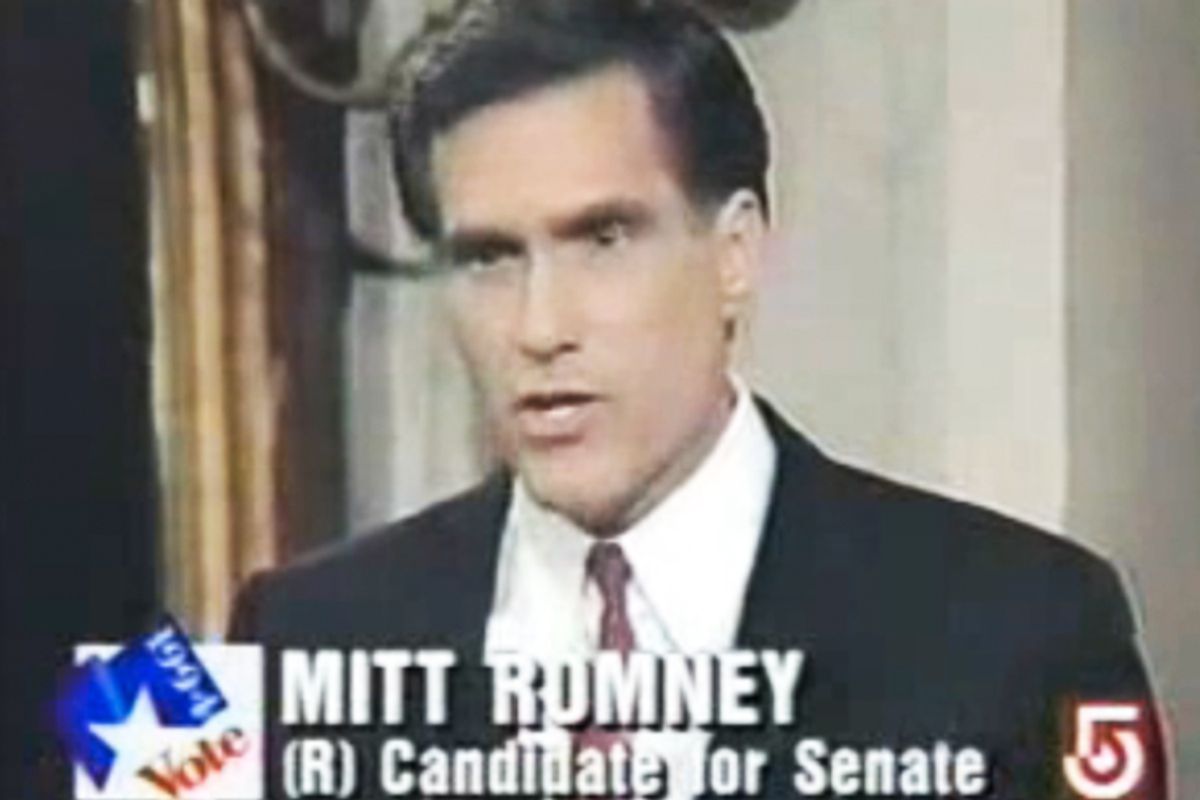

The other reason I believe authenticity matters is much more subjective, and it comes down to this: Isn't there something just a little unsettling about an aspiring national leader who is so fixated on appealing to his constituency of the moment that he's willing to do this:

Shares