Gore Vidal tells of an apocryphal pilgrimage each April 12, the anniversary of Franklin D. Roosevelt's death at Warm Springs, Ga. The trek, organized by the Dutchess County New York Republican Central Committee, supposedly wends its way up the old Albany Post Road from Poughkeepsie to Springwood, FDR's beloved Hyde Park home. According to Vidal, the mythic mission is meant to reassure twitchy Republicans that the 32nd president still rests in something approaching peace at the Hyde Park Presidential Library -- that he has not risen for some new 21st century "rendezvous with destiny."

Fable or not, Roosevelt's mythic resurrection is not just a wisp-of-the-political-wind. Today, perhaps more than any time in generations, the American right seems unable to rest easy until all vestiges of the social welfare programs associated with FDR's New Deal are dead and buried with him.

More imposing (if less charming) than Roosevelt's Hudson River home and library, the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace in Palo Alto is Hyde Park's physical, political and spiritual antipode. Ten miles from California's restless Pacific coast, the 25-story sandstone Spanish-Colonial Hoover Tower is the tallest structure on the forearm of the Peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose. It is part of Stanford University's campus, and it is home to the intellectual cream of the New Deal-phobic American right.

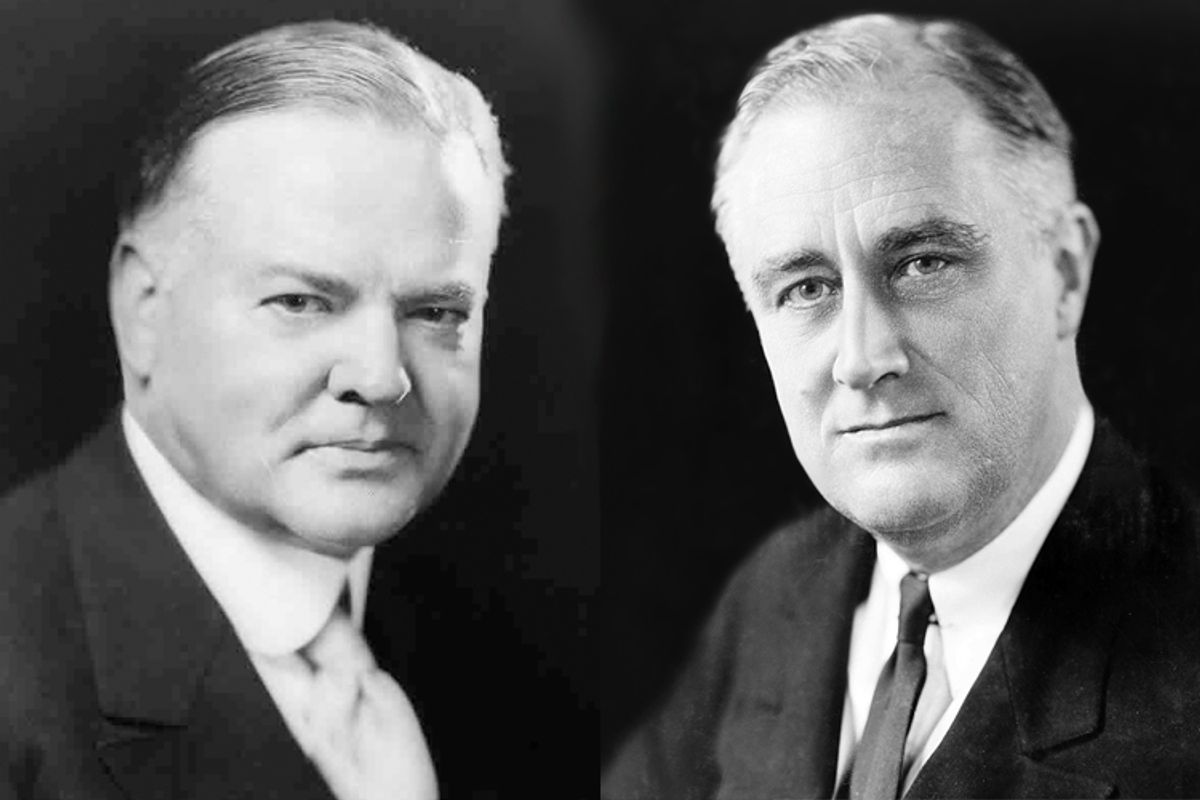

The physical and geographical dissimilarities between the Hoover Institution and Roosevelt Library make a solid gantry for any examination of the fundamental political and personal antagonisms between Franklin Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover and how succeeding generations of their kith have hefted the political cudgel to carry on that fight. Friendly acquaintances early in their careers, the two men became the bitterest of rivals, opponents and ultimately enemies in what was arguably the most momentous clash of American political ideology in the 20th century. In the 1932 presidential campaign, the distinctions could not have been more starkly drawn: New York versus California, city versus frontier, Episcopal urbanity versus Quaker simplicity, yachting versus fly-fishing -- and, most important, government intervention versus economic hands-off.

In '32 it was Roosevelt's "New Deal" that trumped Hoover's "New Day," beginning the unprecedented regime of social and economic interventionism that remains a critical national inflection point, one that Roosevelt partisans still believe saved the republic, and that Hooverites still violently attack as the beginning of the American welfare state.

In this clash, there remains a central enigma in what, with the possible exception of McCarthyism, remains America's most fiercely fought ideological conflict: Why was the uniquely capable Hoover so ill-equipped to meet America's worst economic crisis, while the seemingly out-of-his-depth Roosevelt managed to attack the Depression so effectively? Leave it to the Hooverites. Generation after generation, they have dedicated themselves to chipping away in an obsessive, decades-long campaign to discredit and overturn the "socialistic" theories and practice of the New Deal.

Throughout Roosevelt's never-to-be-equaled 12-year presidency and for over 60 years since, New Deal social welfare policies have rooted themselves in the American political briar patch. Yet, despite the popular acceptance of Social Security, Medicare and the panoply of today's New Deal-inspired social and economic programs, the Hooverite intellectual holding action has successfully fended off the final victory of Roosevelt's liberal vision over Hoover's free-market conservatism. Their ongoing counterattack is informed by the philosophies of Hoover, braced by the work of the institution bearing his name, and paid for by the free-market capitalists who still worship at Hoover's stately Stanford obelisk.

Today, 92 years after its founding, the Hoover Institution continues to venerate free enterprise, from which, according to the organization's mission statement, "springs initiative and ingenuity … in which the Federal Government should undertake no governmental, social or economic action except where local government, or the people, cannot undertake it for themselves." It is a sentiment widely disseminated in institution publications like the "Hoover Digest," a quarterly running stories with titles like "Permanent Tax Cuts: The Best Stimulus," "Why Detroit's Next Chapter Should Be Chapter 11" and other similarly oriented works by rightist public policy thinkers like Daniel Pipes, Victor Davis Hanson, Fouad Ajami and Niall Ferguson.

They and others under the Hoover Institution umbrella are today's intellectual sword-bearers in the Grand Duel between America's 31st and 32nd presidents, which survived Roosevelt's 1945 death and Hoover's 1964 passing. The Duel is a constant presence in the daily discourse of the modern era. In 2009, for example, the New York Times' Adam Cohen rebuked conservative talk show host Monica Crowley for her contention that the New Deal actually prolonged the Great Depression, an exemplar of popular, modern Hooverite doggerel. For his part, Cohen took this as a not so veiled assault on Obama economics -- a viewpoint, according to Cohen, that neither the Americans of the 1930s nor their modern-day heirs would buy. "They knew," wrote Cohen, "that FDR was on their side in a way that Herbert Hoover and his fellow free marketers hadn't been."

"Wonder Boy"

Interestingly, in the decades leading up to the 1932 presidential campaign, Hoover wore the mantle of greatness with as much authority as Roosevelt. A renowned mining engineer and a self-made millionaire by 40, Hoover had become a household name for his work on the Commission for Relief in Belgium, which transported over a billion dollars -- a staggering sum of money in those days -- of aid to citizens of a country subjugated by German marshal law between 1914 and 1918. The program kept millions of Europeans from starving and remains a model for famine relief. Between 1917 and 1919, Hoover also served as U.S. food administrator, virtual dictator of wartime American agricultural production.

It was Hoover's deeply entrenched, organizational turn-of-mind that actually led to his 1919 founding of the Institution bearing his name at his beloved Stanford. The purpose of the Hoover Institution was to act as a conduit and repository for tons of official documents Hoover's agents bought, begged or occasionally stole from participants in the war. He logically believed, according to a former deputy director of the Hoover Institution, Charles Palm, that "if war-related paperwork could be studied and analyzed, future conflicts might be prevented."

Hoover's abilities made him an exemplar of the utopian, ideology-free "master engineers" whose business skills were seen as the path to postwar prosperity. In 1920, Hoover seemed to his neighbor and fellow-Washington up-and-comer, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt, just the man for that year's Democratic presidential nomination. "Hoover," Roosevelt told more than one friend, "is certainly a wonder, and I wish we could make him president of the United States." Intrinsic was the notion that there might be room on such a ticket for Roosevelt -- who did, in fact, parlay his famous name into the Democratic vice presidential nomination that year, part of a ticket that was swept away in the popular desire for the "normalcy" Warren Harding and the GOP were promising.

In 1920, Hoover, who had stubbornly avoided party affiliation, finally declared himself a Republican, and was appointed commerce secretary in the new Harding administration. In the Cabinet, Hoover was regarded as a highly capable busybody. With Harding's August 1923 death, the new president, Calvin Coolidge, clucked at Hoover's stubbornly principled stands on issues like public ownership of radio airwaves, drolly referring to him as "Wonder Boy."

FDR's winter of discontent

For today's liberals, the notion of FDR as a political Rip Van Winkle returning to the Hudson Valley in a political thunderclap is, to say the least, a better prospect than it was in 1982, the Roosevelt centenary. Back then, it was the second year of Ronald Reagan's presidency, a time when the five-decade idea of the New Deal seemed to be in general retreat. It was an era in which "Big Gubment" was the bull's-eye for a muscular new American conservatism. Supporters anticipated the happy irony of Reagan applying his own jaunty, even Rooseveltian, dash towards the task of terminating New Deal-inspired social programs, returning instead to those Hooverite principles of individual self-reliance. It was a time, according to the Roosevelt Library's Cynthia M. Koch, "that Franklin Roosevelt's legacy was very much contested," so much so, she concedes, "that it was even difficult to get a national FDR celebration underway."

That discontented winter of 1982, the Roosevelt/New Deal tide was clearly ebbing in Washington, where the funding for an FDR Tidal Basin monument was bottled up in Congressional committee. Things were not going well at Hyde Park, either. A week before FDR's 100th birthday, fire destroyed one of Springwood's upper floors. Flames scorched the facade, giving the place a look of neglect, if not ruin. In a similar vein, the ongoing debate over FDR's historic place was exemplified by talk about removing his leonine profile from the dime, and even, some Republican partisans muttered, replacing it with Reagan's. The latter was sadly symbolic, particularly considering the role the polio-stricken Roosevelt played in animating the March of Dimes.

Although FDR kept his head on the 10-cent piece, it wasn't without controversy, thanks in part to his legacy in the Joe McCarthy/HUAC Red Scare. While McCarthyism flourished through the late '40s and early '50s, pro-FDR biographers like William Leuchtenburg and James MacGregor Burns seemed obliged to excuse the deals he cut with Stalin at Tehran and Yalta, while assailing "fellow travelers" like Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White whom Roosevelt stood accused of harboring in his administration. In the radical 1960s, Roosevelt's legacy was disparaged for having established the West Coast internment camps for Japanese-Americans, attacked for not paying enough attention to Nazi genocide, declared politically incorrect for hiding his disability and even being, outlandishly, blamed for suppressing intelligence that could have prevented the Pearl Harbor attack.

Even Into the '00s and beyond, FDR biographers felt compelled to include references to Arthur Laffer's "Supply-Side Economics" and Milton Friedman's monetarist theories in an attempt to excuse Roosevelt's increasingly unfashionable Keynesian policies and New Deal social welfare programs in the face of the ascendant Hooverite economic arguments of the Reagan era. Consider, for example, the New York Times bestseller list clash the year before last between neoconservative Amity Shlaes' "The Forgotten Man," which the Nation described as "nothing less than an attempt to reclaim the history of the 1930s for the free market," and liberal Jonathan Alter's "The Defining Moment," unambiguously subtitled "FDR's Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope."

"New Deal, not New Day"

There is a famous photograph taken on March 4, 1933, Day One of those first hundred days, portraying an ebullient Franklin Roosevelt seated next to a dour Herbert Hoover in the presidential limousine on their way to the swearing-in. Though the two men are in physical proximity, they stare out in utterly distinct directions. The photo radiates paradox. Here is Hoover, America's "great engineer," arguably the most competent man in the world to address a national economic emergency. And yet, he is clearly a beaten man, grumpily ceding power to Roosevelt, a man seemingly unprepared for the challenge -- a 51-year-old scion of Hudson River wealth, a stamp-collecting dilettante with limited executive experience, a man with legs so weakened by poliomyelitis that he had to be surreptitiously lifted into and out of the presidential limousine. A year earlier, Washington's alpha-journalist, Walter Lippmann, faintly damned Roosevelt as "a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president."

By Election Day '32, however, it was clear that Roosevelt was tapping into a phenomenal political aquifer. Hoover's so-called "New Day" was buried by Roosevelt's promise of a "New Deal." Even if that deal was light on specifics, Americans were growing to like the messenger. With a commanding lead going into the election, Roosevelt played it safe, embracing conventional thinking, calling, for example, for today's equally wrong-headed political ne plus ultra: a balanced budget. It didn't matter. "Vote for Roosevelt," one wag telegraphed Hoover, "make it unanimous!"

The '32 campaign was, above all else, about confidence and connection. Hoover, for all his intelligence and energy, seemed emotionally incapable of striking that right, reassuring note. It was, in fact, Hoover who first applied the then-voguish Freudian construction "depression" to the crisis, according to historian Robert McElvaine, because "it had a less ominous ring than the previously used descriptors, 'panic' and 'crisis.' " While Hoover wanted a stuffy "Bank Moratorium," Roosevelt instead called for the more buoyant "Bank Holiday." Hoover's tin ear extended to music. He invited heartthrob crooner Rudy Vallee to the White House, promising him a medal if Vallee would "write a great song to drive the Depression away."

With his icy technocratic persona, Hoover was simply the wrong man to break out into "Happy Days Are Here Again," and thus reassure frightened Americans. Urban shantytowns were called "Hoovervilles"; armadillos, said to taste like pork, became "Hoover hogs"; empty inside-out pockets were "Hoover flags"; newspapers stuffed inside clothing to ward off the cold, "Hoover blankets"; and empty freight cars, "Hoover Pullmans." America's comedic conscience, Will Rogers, summed up the relative regard in which Hoover and Roosevelt were held in the dismal winter of 1933:

"If you bite into an apple and find a worm, it's Hoover's fault."

"If the capitol burned down," people would say, well, at least Roosevelt built a great fire."

Hero, not Nero

Hoover's failures were not for lack of effort. Despite popular conviction, he was no American Nero, fiddling inside the Oval Office while the country burned. Hoover funded public work and relief programs at then-unprecedented levels. He used the presidential "bully pulpit" as capably as anyone since FDR's late cousin, Theodore. Hoover jawboned businesses to prevent them from cutting workers' wages. He pushed through a moratorium on World War I-related German reparations. Hoover also encouraged the private sector to create its own self-help organizations, including the Federal Farm Bureau, National Business Survey Conference and National Credit Corporation.

Unfortunately, his good decisions were overmatched by the disastrous ones. In 1930, against the advice of leading economists, Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, effectively slaughtering international trade and devastating already distressed American agriculture and livestock production. Similarly debilitating was the 1932 Revenue Act, a tax-increase that led, disastrously, to a severe contraction of the money supply. By 1933, so little legal tender was in circulation that alternative "scrip" was circulated in many American towns and cities.

In the end, Hoover's belief in the power of volunteerism and reliance on the "wisdom of the market" simply didn't work. Roosevelt hammered home the point in his acceptance speech at the '32 Democratic convention in Chicago: "Our Republican leaders tell us economic laws -- sacred, inviolable, unchangeable -- cause panics which no one could prevent. But while they prate of economic laws, men and women are starving. We must lay hold of the fact that economic laws are not made by nature. They are made by human beings."

"Bold, persistent experimentation"

Even if his efforts during the interregnum were as ineffective as his campaign, Hoover soldiered gamely on into his administration's final hours. An eel-like Roosevelt slipped through Hoover's grasp, ignoring or missing meetings, avoiding contact and generally failing to show solidarity with the very-soon-to-be ex-president. Roosevelt's snubs infuriated Hoover, who began to view his successor as a cad willing to let the economy collapse simply because, at least according to the Hoover Institution's Charles Palm, "Roosevelt didn't want to be tied in any way to Hoover."

The American public would forgive Roosevelt for distancing himself from his predecessor. His infectious confidence was enough, with or without Hoover's assistance, to raise the pulse of a nearly moribund national economy. "The country needs, and unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation," Roosevelt told an electrified Minnesota college audience. Once in power, Roosevelt had few qualms about adding Hoover's programs to his own New Deal. By then he needed all the help he could get.

By Inauguration Day 1933, a quarter of America's banks were shuttered and business was flat-lining. The steel industry, an important economic predictor, was operating at a disastrous 12 percent capacity. Signs of the crisis were everywhere, and action, even action for its own sake, the order of the day. In cities across the nation, pay cuts, layoffs, lockouts and shutdowns were leading to massive civil unrest and general strikes. The previous year, at Ford's River Rouge factory in Dearborn, workers fought pitched battles against Henry Ford's private security forces, leaving four dead and 50 injured.

In the spring of '32, the crisis had reached Washington, D.C., in the form of a tattered "army" of World War I veterans marching to demand that bonuses scheduled for 1945 be paid immediately. Leading Army troops who ultimately broke up "Bonus March" encampments, Gen. Douglas MacArthur minced no words about the crisis. The marchers, he said, were "a mob animated by the essence of revolution." The martinet MacArthur was not alone in imagining the U.S. subsumed in a red tide. John Steinbeck in his Depression epic "The Grapes of Wrath," described the national mood in terms of a question: "How can you frighten a man whose hunger is not only in his own cramped stomach but in the wretched bellies of his children? You can't scare him -- he has known a fear beyond every other."

The man on horseback

Against this backdrop, a spent Hoover departed Washington on the third day of March 1933 for his home on the Stanford campus. Over the next dozen years, he would vituperate again and again against Roosevelt's seemingly mystical ability to direct the national conversation. What Hoover never understood was that beneath the Roosevelt charm lurked, with the possible exception of Lincoln, the most skilled, complex and cold-blooded political operative in American history. A list of potential rivals dispatched by Roosevelt attests to this point; they were among the era's most powerful and perfidious: Al Smith, Huey Long, Charles Lindbergh, Joseph P. Kennedy, William Randolph Hearst, Wendell Willkie, Henry Wallace and Herbert Hoover. Each would make the mistake of underestimating Roosevelt and pay with his political future. In a 1938 New York Times Magazine profile, the author focused on the eyes as a possible route into the complex, mandarin Roosevelt mind: "A cool Wedgewood blue … as keen, curious, friendly and impenetrable as ever" was the report.

Thanks in part to Roosevelt's enmity, Hoover remained sidelined, a reviled figure, blamed, unfairly or not, for the Depression. Hoover countered with a literary barrage against the new president and his New Deal. In a 1934 book, "The Challenge to Liberty," Hoover discussed the dangers of economic intervention in terms of the loss of individual liberties. "We have to determine," Hoover wrote with surprising heat, "whether under the pressure of the hour, we must cripple or abandon the heritage of liberty for some new philosophy which must mark the passing of freedom." It was an argument that would be taken up by succeeding generations of Hooverites. Finally, Hoover warned of "the man on horseback, ascending triumphantly to office on the steps of the constitutional processes." There was little doubt to whose steps Hoover was referring.

Franklin Rex?

To this day, the "man on horseback" taunt haunts Roosevelt. It is evident in Gore Vidal's description of FDR as "the second in an American royal line that began with Theodore Rex and the Great White Fleet, and continued in its boisterous pursuit of empire under Franklin." In his 2000 novel, "The Golden Age," Vidal presents a tragic, determined Hoover trying from bitter exile to slow Roosevelt's headlong rush to war. "I see something worse than war," Vidal has Hoover explain in words that are Vidal's, but which resonate with Hoover's own. "I am certain," Vidal's Hoover continues, "that the next war will absolutely transform us. I see more power going to the great corporations. More power to the government. Less power to the people."

There were undeniable dictatorial impulses lurking within the New Deal. There was, for example, Gen. Hugh S. Johnson, chief of the National Recovery Administration, which Johnson immodestly referred to as "the greatest social and economic experiment of our age." In the New Deal's early days, the NRA "Blue Eagle" became a ubiquitous Depression-fighting icon hung in shops, stores and factories. This NRA was a massive and sometimes ham-fisted program aimed at realigning the relationship between industry, labor and agriculture, and which, in 1935, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional. In retort, the boisterous Johnson, Time's 1933 Man of the Year, produced "A Proclamation" whose fictional author he named "MUSCLEINNY, Dictator pro tem." Johnson's fascist-tinged, tongue-in-cheek fantasy illustrated the search in some quarters for a goose-stepping replacement for what seemed to some to be dying American democracy.

While FDR's declaration of a "Bank Holiday" on his second day in office may have stretched the bounds of presidential authority, he did not, as many supporters and newspaper editorialists urged, militarize the New Deal. With a belief in the market, and an uncanny feel for the fundamentally optimistic American soul, FDR was the best, and quite possibly the last, great hope for American capitalist democracy even if conservatives continued to mistake him for Hugh Johnson's American "MUSCLEINNY." Yet even a free-marketeer like Forbes publisher Rich Karlgaard extols Roosevelt's decision to govern constitutionally as "an extraordinary accomplishment that held together both America's economic and political center even when alternative models across the Atlantic appeared to be working better."

A traitor to his class?

If FDR was no Augustus to Theodore's Julius, was he, in the celebrated phrase of the day, "a traitor to his class?" Such was the droll insinuation of Peter Arno's September 1936 New Yorker cartoon published with Roosevelt on the brink of a reelection landslide. In the cartoon, a trio of Arno's primped, DAR dowagers gleefully urges a group of their friends to join them for a bit of sport: "Let's go down to the Trans-Lux," one says, "and hiss Roosevelt!"

FDR certainly knew how to pick his enemies. Certainly, Lowell Weicker Sr., a New York industrialist and Squibb Pharmaceutical chairman, thought of Roosevelt as just such a traitor. Into the mid-1970s, Weicker Sr. could be reduced to spluttering at his Locust Valley dinner table at the mere suggestion made by historian Robert McElvain in his book "The Great Depression" that FDR "was capitalism's savior not its executioner." Interestingly, Weicker's son, Lowell Weicker Jr., a former Connecticut senator and governor, acknowledges that during the Roosevelt years, "there was clearly general antipathy towards FDR among the better-to-do." But as with everything Roosevelt-related, things at the Weicker household were not quite as rock-ribbed as they might have seemed. Although he began as a Republican, Weicker Jr., differed from his father, believing that "along with Lincoln and Truman, Roosevelt was the greatest president America ever had." And while Weicker Jr. spent most of his political career as a Republican, he often lined up with Senate Democrats in the 1980s to block his fellow Republicans' attempts to repeal or weaken programs originating in the New Deal. (Weicker ultimately left the GOP after being defeated for reelection in 1988, then was elected governor two years later as an independent.)

Today, Roosevelt still draws the enmity of the "rich-right," and would be the first to stir the stormy critical waters he loved to dare, as he did in the speech he gave at Madison Square Garden immediately prior to the '36 election. In that oration, Roosevelt gleefully gouged "the old enemies of peace; business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, and war profiteering." "Never before," Roosevelt called out in his famously jovial sing-song cadence, "in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me," he thundered about the ruling class, "and I welcome their hatred!"

From the left edge of the American political escarpment comes a different kind of hissing about the New Deal. It is the argument that possibly the greatest effect of FDR's efforts was the ultimate co-option of any true American left. The argument is that so deeply did the New Deal insinuate itself into the American political bloodstream that there were simply not enough red cells remaining to develop effective Communist or Socialist political fronts. "Did FDR co-opt the left?" rhetorically asks Frank Roosevelt, a professor at Sarah Lawrence College. An economist, he admits, "of the leftist persuasion," Frank Roosevelt, who is in fact, Franklin Delano Roosevelt III, answers the question about his grandfather in a way that illuminates the inextricable connection between American politics past and present. "Yes, FDR did save capitalism," Frank Roosevelt agrees, "but it would have been nice if he had included healthcare!"

Did the New Deal prolong the Depression?

The most contentious question animating the duel between the supporters of FDR and the Hooverites is whether the New Deal ended the Great Depression or actually prolonged it, as Amity Shlaes recently argued in "The Forgotten Man."

Indeed, in 1937, as a reenergized economy seemed to be edging out of the Depression, another downturn hit, plunging America back into economic crisis. There are those economists like Berkeley's John McArthur, whose "Making Markets Work" argues that "the new downturn turned severe because an overly-optimistic Administration pulled the plug on New Deal programs at the same time it raised taxes." Shlaes doesn't buy it, believing that by 1938, "there was a new sense of permanence about the Depression." The case could equally be made that today's tenuous recovery is similarly in danger due to a Republican Party short-circuiting the current recovery by killing job-producing programs before they can be fully effective.

Slowing down the New Deal in 1938, which Roosevelt felt forced to do, meant that full employment would not be reached until the wartime year 1942. Yet the Republican attempt to strangle the New Deal in no way mitigated the ultimate effect of Roosevelt's programs, which MacArthur argues was "nothing less than a revision of the American social compact." Despite current rightist outcries to the contrary, out of the New Deal came general consensus that unregulated capitalism could never again be allowed to run rampant as it had in 1929, and that it was the government's responsibility to provide a safety net to citizens in distress.

There was another epochal effect of the New Deal, which was the rescue of a generation from the despair of the "Hoovervilles" -- breadlines and sharecropper hovels. These were the Depression-era youth employed in the Civilian Conservation Corp, Farm Security Administration, Public Works Administration, and other of the New Deal "alphabet soup" of work programs. In all of them, young men and women could work and learn, as well as send vitally needed wages home. Ignored, this generation could easily have been shock troops in a rising that would have ended American democracy. Instead, they were the millions prepped to serve their nation in a World War in defense of freedom and democracy. The Roosevelt Library's Koch believes strongly that "it is a false dichotomy to separate the New Deal from World War II." Rather, she says, "victory in the War was the culmination of New Deal principles applied on a worldwide stage."

The real forgotten man?

The title of Shlaes' "The Forgotten Man," comes from a speech given by FDR shortly after his inauguration. In it, he called for Americans to "put their faith in the 'forgotten man' at the bottom of the economic pyramid." In the momentous dozen years that followed, it could be argued that Herbert Hoover was America's true "forgotten man."

Only with Roosevelt's April 1945 death came some measure of absolution for Hoover, this in the wildly unlikely guise of the new president, Harry S. Truman. Within months of taking office, Truman invited Hoover to the White House to discuss a subject about which the ex-president was still master -- feeding the starving in the backwash of war. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship between the two men. Truman then asked Hoover to apply his expertise to reorganizing American government. Over the next dozen years, Hoover chaired various so-called "Hoover Commissions" working to streamline elements of government. He even came up with the heretical, tongue-in-cheek notion of granting baseball batters an additional strike, designed, Hoover suggested, "to get more men on base."

Into the 1960s, Hoover burnished his image as America's "elder statesman." He was an early booster of a young Southern Californian lawyer and Navy vet, Richard Nixon; Hoover sponsored Nixon as a member of Northern California's celebrated Bohemian Grove encampment. Before his death in 1964, Hoover shared his simple, salty strategy for surviving the Grand Duel with FDR and the New Deal: "I outlived the bastards!"

The duel goes on

The Roosevelt/Hoover Grand Duel continues to be fought at fascinating times and places. There was the August 2007 appearance by Amity Shlaes in Ellsworth, Maine, to discuss "The Forgotten Man" at a forum sponsored by a local newspaper, the Ellsworth American. Vacationing at his nearby summer home, Frank Roosevelt felt compelled to attend. At the end of Shlaes' presentation, Roosevelt stood, introduced himself, and spoke in defense of his grandfather's legacy. He professed disappointment at what he called "the selective anecdotes of a few people hurt by the New Deal" that, in his view, form the backbone of Shlaes' narrative. As Roosevelt explained to the audience, "it was simply unfair to the millions of people for whom the New Deal was literally a gift from heaven." Not that you are likely to be able to convince the latest generation of Hooverites, for whom, seemingly, even the ghost of the man is an existential threat requiring those yearly graveside visits to assure that, however restive his soul, the great man still resides in his crypt in the garden at Hyde Park.

Richard Rapaport is completing "Joe's Boys," a biography of the young men around Sen. Joseph McCarthy. He can be reached at: rjrap@aol.com

Shares