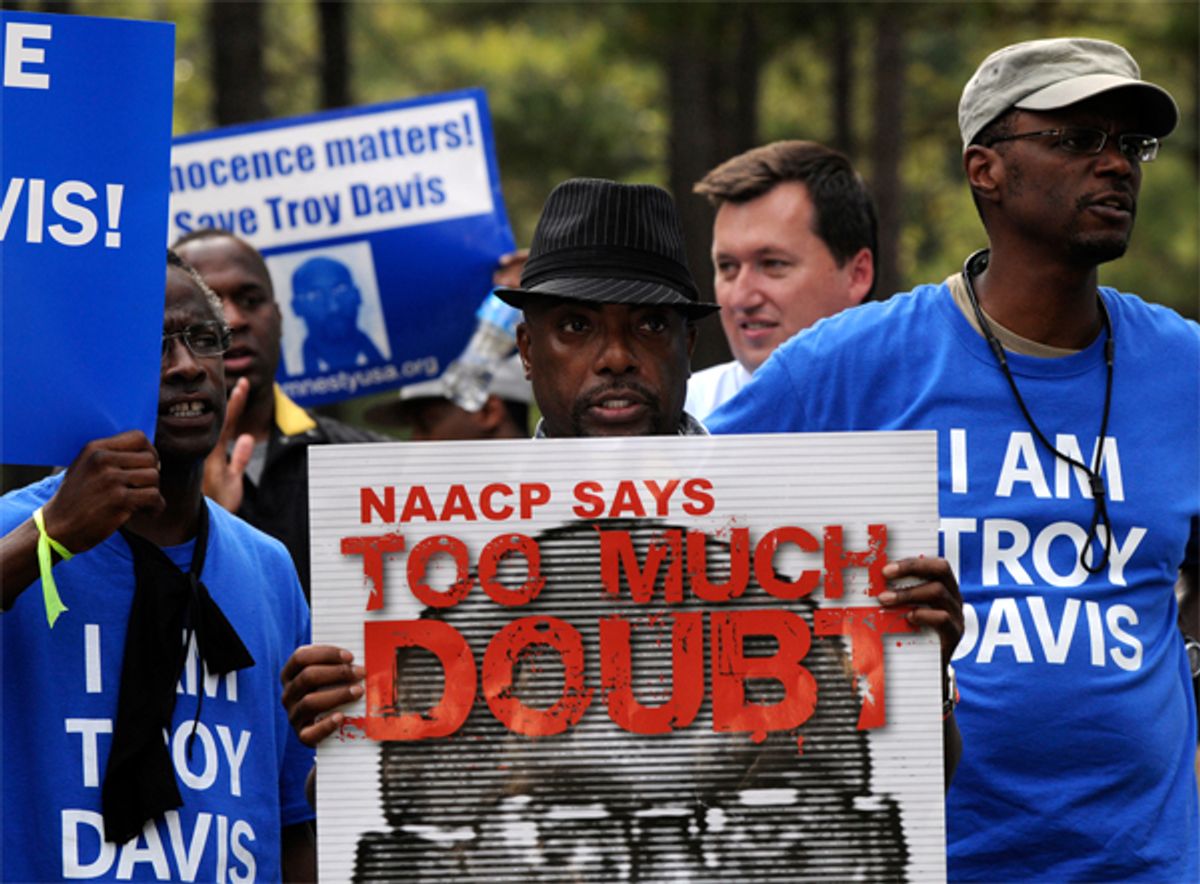

Troy Davis was killed last night by the state of Georgia, for the murder of off-duty police officer Mark MacPhail. His conviction was based solely on eyewitness testimony, and many of those eyewitnesses later recanted their stories. There was never any physical evidence linking him to the crime. But he lost numerous appeals and was finally denied a stay of execution by the Supreme Court.

I would think, if the nation is unwilling to abandon the death penalty (in large part because the death penalty remains quite popular), that it would be reasonable to at least restrict its usage further. Maybe, for example, it should be prohibited in cases where there is no physical evidence tying the defendant to the crime. But an appeal to "reason" is impossible when one side is arguing from a position of doubt and skepticism and the other side simply doesn't care.

I looked for right-wing responses to the execution and found that it simply wasn't much of a story on their side. The National Review Online and the Weekly Standard seem wholly uninterested in it, leaving the defense of the execution to the conservative movement's left-baiting id. Like Ann Coulter, who endlessly repeated the shibboleth "cop-killer," and former HuffPo troll Greg Gutfeld, who focused, as always, on the true villains in this story: Hollywood celebrities who surely only adopted a cause because it's fashionable. (It is fashionable to oppose the execution of a man whose guilt is in doubt!)

Erick Erickson wrote a couple of posts on Davis last night, including an open thread asking how the execution would affect "the horserace" and one revisiting the prosecution's case and declaring it airtight, without actually addressing any of the flaws in how that case was put together and presented. There was evidence that implicated Davis -- he might have been guilty! -- but the point, the entire argument, is that by no means was this man so patently, self-evidently guilty that Georgia should feel comfortable killing him. The point is doubt, but one side believes "doubt" is a moral failing.

The New Republic, meanwhile, reprinted an old magazine piece criticizing death penalty opponents for focusing on death-row inmates whose guilt is in doubt rather than "devoting more time and energy to more significant ... problems with capital punishment." (There's a case to be made that anti-death penalty activists should behave more like antiabortion organizations, attacking the policy by lobbying for state-by-state piecemeal restrictions rather than campaigning nationally for a blanket ban. There is also a case to be made that they're already doing this, with notable success in most states that aren't part of the old Confederacy.)

The sad fact is, the Davis case is an example of the system working precisely as it was designed to work. This is why the Supreme Court and the Georgia Board of Pardons denied his pleas for clemency. There was no violation of the rules governing capital punishment -- the rules simply don't protect people who may have been wrongfully convicted, if a jury was convinced by meager and questionably obtained "proof."

Here it devolves again into debates between tribes that aren't speaking the same language. The liberal argument that it's hypocritical to call yourself pro-life and support the death penalty is facile -- an evangelical Christian quite easily distinguishes between an innocent person killed before birth and a man who had a chance at life and failed to live righteously -- and while the argument that those who don't trust the government to regulate business or provide healthcare shouldn't trust it to put men to death is a bit more compelling, guilty verdicts are meted out by juries of citizens, not "bureaucrats," and even the most staunch anti-government conservative respects the state's right to enforce "law and order."

So, sadly, I don't think the execution of Troy Davis will have much effect on the national "conversation" about the morality of capital punishment or the glaring flaws in America's system of justice. Because while it's very reasonable to argue that "we" should only kill someone if we're really, really, really sure they did it, the modern American conservative is really, really, really sure about everything.

Shares