Among the mainly Jewish, determinedly world-weary kids I hung with in high school in the mid-'60s, it was fashionable when confronted by any challenge to throw up hands in mock despair and cry, "Oh God, I'm having an identity crisis." Smart, affluent, heavily psychologized and headed for good colleges, we thought this was a joke.

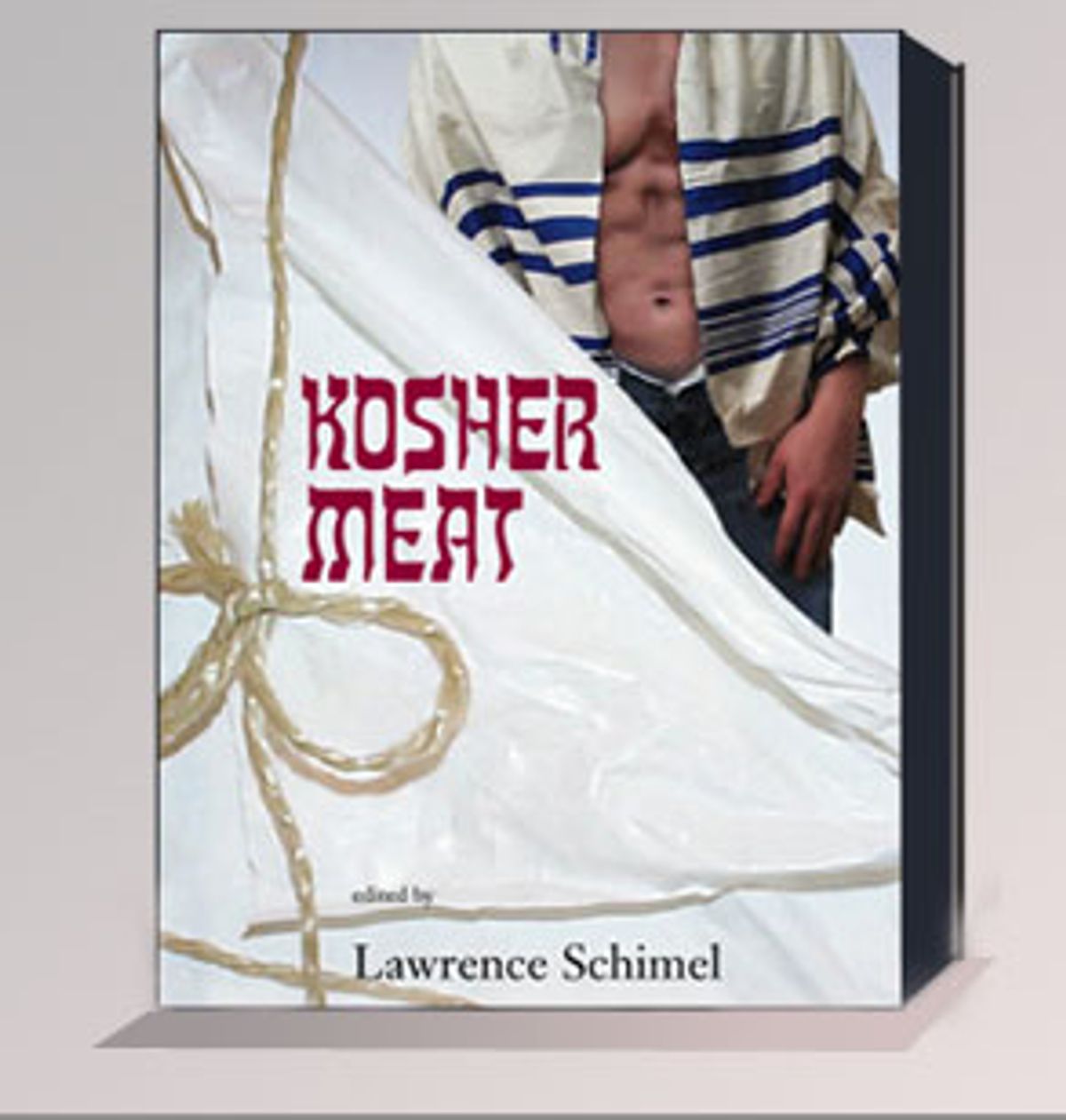

As the 10 stories by gay men in Lawrence Schimel's new anthology "Kosher Meat" illustrate, a Jew in America never seems to resolve the burning questions of his identity; those of us among the chosen people who also turn out to be queer go through life taking identity crisis, so to speak, at both ends.

Underlying our conflicted self-concepts are two things about Judaism that reflect its odd duality as both a religion and a people. One is the Torah's contradictory messages about homosexuality: Leviticus tells us it's an abomination, but then there is that glorious passion of Jonathan and David. This ambiguous message is compounded by the legendary love of Jewish mothers for their sons that is, often enough, undiminished when the sons turn out to be faygelach. My own mother, intuiting that I was queer, protected and supported me in many ways -- although she died when I was 16, well before changing social mores would have encouraged her to verbalize it, even to herself. I often wonder what to make of the fact that, stuck for names, she read the Bible while recovering from my birth and came up with Jonathan David. "Miz Lerner," a nurse is supposed to have declared, "you're just the most sanctified woman we've seen."

The other confusing message we get from Judaism is the imperative to do our part in ensuring survival of the tribe. Accepting being gay is an act of self-love and self-respect. Self-love and respect, for Jews, naturally extends to our roots, and it doesn't take much knowledge of the history to feel proud of our survival. "Be fruitful and multiply" is the biblical commandment. The standard joke is that this is actually expressed to us as the threat that it will kill our parents if we don't produce darling grandchildren on whom they can dote. But having children is something few Jewish queers, however otherwise gifted, will achieve. You might be surprised how much anguish this can cause us, never mind what it does to our parents.

Gays like to think that we can nearly always recognize one another -- even those who are not "obvious." We call this keen discernment "gaydar," and pretend it's innate, but it's actually something we've trained ourselves to do. Though the particular signals are different, it's much the same with Jews, who can be just as skilled as gays at picking one another out in a crowd. My parents and the liberal, suburban, mostly secularized Jews I grew up among somehow programmed me to automatically examine the name and features of every single person I ever meet for the possibility of Jewishness.

In the 10 years since I came out as gay, I've had two principal relationships -- one a relatively short disaster, and one a lasting dream -- with gentile men, both of whom I mistook at first for Jews. This suggests that I ought to disengage my faulty Jewdar. Except that I can't. Uncertain as it is -- just like my gaydar -- it's a survival skill I'm afraid to be without.

The characters in "Kosher Meat" are forever trying to work out who they are as Jews, as well as to pinpoint the ethnic identities of the men they're attracted to. One of Jonathan Wald's characters experiences a crescendo of sexual pleasure with an Aryan-looking Fire Island trick he thinks of as "the Nazi," only to find that the trick's obviously Jewish roommate is someone he might have preferred, someone he could actually imagine a relationship with. A San Franciscan in a story by David O'Steinberg, during a nighttime encounter in a Tel Aviv park, says, "I stood shocked, stunned -- a Jewish man getting his boots licked hard by an Israeli -- what did it mean?"

This quote, and the book's title, suggests porn -- porn with a Yiddish accent, maybe, exhortations to "Eat, dolling," penetration with half-sour pickles, jokes based on the famous sign in Katz's Delicatessen on the Lower East Side of Manhattan: Send a Salami to Your Boy in the Army. Of course there is sex here, but it's nearly all experienced in the course of (mostly unfulfilled) pursuits of identity.

Michael Lassell, for example, has elsewhere published some of the bluntest -- not to say bleakest -- descriptions of gay sex in print. But the shtupping in his present story occurs chastely, offstage -- between a man who had a single Jewish great-grandparent, but no Jewish upbringing (and who yet can say, "I have the feelings. The longing ... The Wandering Jew thing. I was tortured for not being Jewish in my high school, which was almost entirely Jewish.") and a man whose grandparents died in the camps and who as a child decided to change his first name to Sariel, an anagram of Israel. These two cruise each other and hook up while in Washington touring the Holocaust Museum, a venue sure to focus the mind on issues of ethnicity, if not guaranteed to excite a hard-on.

Nearly all the situations in these stories are seen through similar overlays of modern irony: the Jewish boyfriend whose Polish-refugee father had been afraid to have him marked for life by circumcision; the Catholic who tries disastrously to jolly his Jewish boyfriend's mother out of regretting her son's gayness, and his likely lack of progeny, by saying, "It's not as if we won't know in which religion to raise the children"; the San Francisco duo who carry on communication in their fetishized daddy-boy scene with the few scraps of Yiddish they know. The only exception is a magic realist tale by Andrew Ramer, author of several volumes of gay mytho-history, which is set in biblical-era Judea. It's the only one in the book that's sweet as milk and honey, too.

With that exception, the ruminations of the men in "Kosher Meat" add their particularly this-minute, self-absorbed convolution to the ongoing literary exploration of how being Jewish and being queer overlap. This grand project, apparently nowhere near exhausted yet, includes titles ranging from "Friday the Rabbi Wore Lace: Jewish Lesbian Erotica" to "Out of Our Kitchen Closets: San Francisco Gay Jewish Cooking" (Gevalt! Now there's such a thing as gay cooking?) In its obsession with the merging and diverging of identities, it also echoes the numerous similar anthologies by American queers of African, Asian, Hispanic, Pacific Island and American Indian descent.

Lawrence Schimel is a prolific writer, poet and anthologist whose 40-some books range from erotica to science fiction, and even to food (eat, dolling). His "PoMoSexuals: Challenging Assumptions About Gender and Sexuality" (co-edited with Carol Queen) won a Lambda Literary Award, the Pulitzer of gay writing, in 1998.

I liked Schimel's story in "Kosher Meat" about a sex party among a group of jittery guys who know each other from their (no doubt Reconstructionist) congregation. One of them brings along an uninvited outsider -- a Puerto Rican pick up, uncircumcised, a non-Jew -- whose simple presence enables the rest to cut loose and pile on. But I'm afraid Schimel's afterword -- a longish rumination on connections between Zionism, the changing attitudes among American Jews toward Israel, these same Jewish Americans' perpetual identity crises and the similarly shifting layers of gay self-consciousness -- will lose most non-Jewish readers. It bored me, and I got all the references. Better he should have submitted it to the editors at Tikkun, and made room in his book for another revealing account of Jewish gay mishigas.

Shares