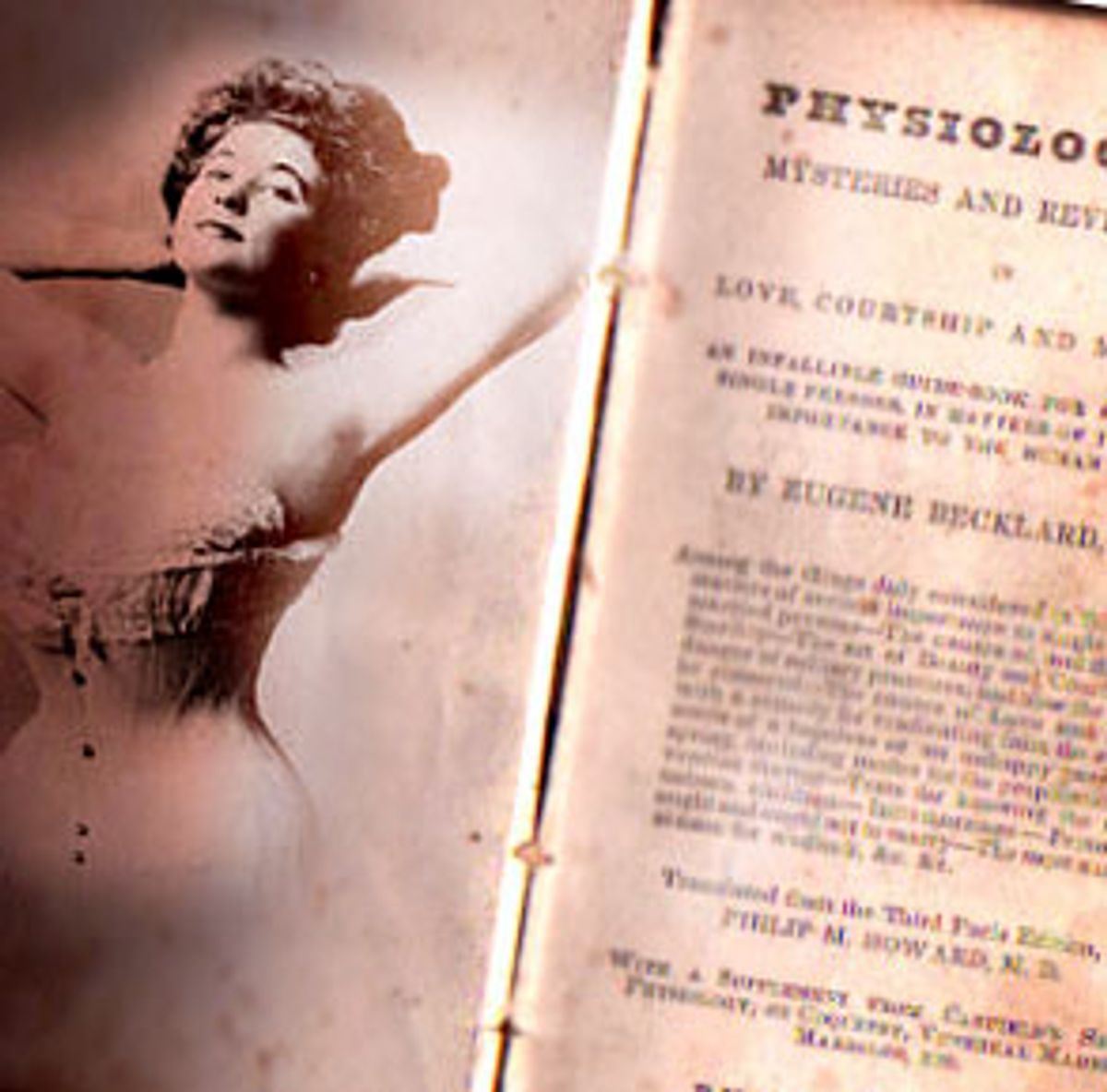

I don't know what a copy of "Becklard's Physiology" was doing in a cardboard box outside a junk shop, jumbled among Barbara Cartland paperbacks, and priced at 25 cents. It's not in mint condition, but the binding is mostly intact, and the pages are legible and only mildly mildewed. And it's from 1845. It's 157 years old!

Better still, it's not Dickens or Hazlitt or anything classic -- it's a shabby treatise on human sexuality, evidently written for a mass audience: a sort of "Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask)" for the early Victorian era. (Its full title is even longer than Dr. Reuben's: "Physiological mysteries and revelations in love, courtship and marriage: an infallible guide-book for married and single persons, in matters of the utmost importance to the human race.")

This may not be as momentous as the discovery of Thomas Traherne's previously uncelebrated poems in a bookseller's cart several decades after his death, but it has given me much pleasure and, perhaps, a little insight into the mechanics of self-help bestsellership.

Neither the book's author, the French physiologist Eugene Becklard, M.D., nor his translator for this American edition, Philip M. Howard, turn up in Web searches, save for a listing of a duplicate volume in the Rutgers Library. I don't even know if those are their real names. In fact, I prefer to believe that "Becklard" and "Howard" were in fact one and the same literary shyster, using distinguished-sounding cognomens to lend authority to his little volume.

Notwithstanding its current anonymity, I expect that this book was a great hit in its day. (Rutgers' copy is from 1850, so it had a few editions at least.) Not that Becklard's remedies have any scientific value: They are mostly nonsense, occasionally even dangerous nonsense. But using a formula that yet serves the self-help gurus of today, Becklard fulfills admirably what remains the primary function of such authors: He validates. He shows sympathy for his readers, flatters their prejudices and, in a gentle, nonjudgmental tone, guides them toward enlightened solutions to their difficulties.

Becklard dispenses some medical advice, treating conception, pregnancy and childbirth, as well as psychosexual irregularities ranging from onanism to frigidity. Alas, his store of genuine medical knowledge is meager. "The mouth of the uterus, be it known, is very narrow," he states, "so narrow in fact, that the fecundating principle would not enter it, but that it craves it, and inhales it by real suction -- a proof, by the way, that a rape can never be productive of real offspring."

He also believes that "the party, whose temperament predominates in the child, was in the highest state of orgasm at the period of intercourse." For difficulties in achieving either fertility or potency, Becklard prescribes a concoction called the "Lucina Cordial," apparently so well known in his age that he doesn't bother to name its contents, though he does repeat some anecdotes attesting to its power. ("I was applied to by an Irish gentleman and lady, both of very cold natures, who were blessed with offspring after the mutual use of five bottles.") If the Cordial is not to be had, adds Becklard, "Verrey's Tincture" will do.

Despite this appalling ignorance, Becklard is most persuasive in extending hope to those who feel themselves sexually unfortunate or inadequate. Take women judged physically unable to conceive -- a grim sentence in that time. "Such things, they tell us, have been," Becklard assures, "but I have never seen any proof of it; and I believe it will be conceded to me, that I have had as much anatomical experience as any man in France." (And that's saying something!)

The real cause of unfruitfulness, says Becklard, is improper mating. "For example, it is not to be expected that much happiness" -- meaning here, reproduction -- "can attend the union of a lymphatic man, with a sanguine woman, and vice-versa." (Not to mention those who find "their physical conformations are unsuited to each other; and hence, they cannot duly realize the most important of the enjoyments of wedlock.") In these regrettable circumstances, he approves divorce; to head them off, he favors a trial period of premarital relations: "I prefer the old Scottish fashion of 'hand-fasting,' for a time, to that of taking things on chance, without any future honorable alternative." (Hand-fasting was a kind of official trial marriage, granting pagan Scot couples full conjugal access and the right to separate afterward without calumny; it is still practiced today by Wiccans, the Universal Life Church and people who are really into Braveheart.)

For those who have the problem opposite to infertility, Becklard discourses on methods to undo conception, without resorting to means that may "tend to promote the commission of a crime." Immediately after the conjugal act, "dancing about the room before repose, for a few minutes, might probably have that effect" the reader desires, he whispers; "but trotting a horse briskly over a rough road on the following day would ensure it." "Strong victuals" and "spirits that promote thirst" are also "great enemies to reproduction."

Lest we think the author a thoroughgoing libertine, Becklard lets it be known that some things are not to be countenanced -- but for rational, not religious, reasons. "Solitary practices" in the young are discouraged because "they arrest the growth of stature; and while they stop the growth of the organs, and the development of the various functions, bring on early puberty; that is, they produce an artificial ripeness which must soon wither and dry up ... indeed, the confirmed onanist becomes incapable of consummating the rights of marriage." When one suspects such a malefactor, says Becklard, one must "put this little volume in his hands -- a perusal of which, by clearly informing him of his danger, will effectually cure him of his bad habits."

The remarkable thing about "Becklard's Physiology" is that, while his language and superstitions now seem absurd, his method is completely contemporary.

Knowing that feelings of sexual discontent are usually accompanied by great shame, Becklard gently assures his readers that there is nothing shameful about reading his book; indeed, he urges that they share its contents with their children, for "is it not rather injustice and cruelty to deprive them of a knowledge, the want of which may involve them in unhappy marriages, or leave them the victims of habits (about whose evil effects they have never formed an idea), which may terminate in consumption, imbecility, and even madness?"

He even sets himself up as a bit of a renegade, occasionally drawing distinctions between his own and other contemporary points of views, both traditional ("the absurd notions of Martin, Liceto, Stultz, Malthus ...") and heterodox ("This preliminary chapter ... was principally written to correct a notion which seems to prevail in the community, that I am a convert to the [to me obnoxious] doctrines of Madame George Sand").

And despite many formal obeisances to the conventions of his time, Becklard's attitude is what a later age would call sex-positive. His underlying theme is the necessity of sex, his cause the removal of all impediments to its full, healthful enjoyment. ("It is better," he writes, "to give way to nature, no matter how rashly, if diseases are avoided, than to resist her altogether.") It's not hard to imagine him, after a brief initial shock, coolly surveying the erotic antipodes laid out by the Tristan Taorminos and Dan Savages of our own time, and judging them reasonable alternatives to hand-fasting.

His tone is lofty, but his means of promulgation are colloquial, even vulgar. He chats amiably about standards of beauty and courtship ("Making love by flowers, as they do in the East, is a very beautiful mode, and avoids much embarrassment"). He tells stories. The book's afterword, a "Supplement From Canfield's Sexual Physiology," is mostly made up of metaphorical sex gags ("The skill of man is unequal to the formation of a new man from old materials, but the battered tenement may, with care, be long sustained by props").

He is, in short, a forgiving expert witness, a helpful friend and an easy read. Change his frock coat to a three-piece suit, spice up his lingo and he is ready for Oprah. In fact, since reading this book, I can't look at Wayne Dyer, or Philip C. McGraw, or any of the other modern self-helpers, without seeing in their self-satisfied smiles the shade of old Eugene Becklard, pleased to see that while the state of medicine changes daily, the status of snake oil is eternal.

Shares