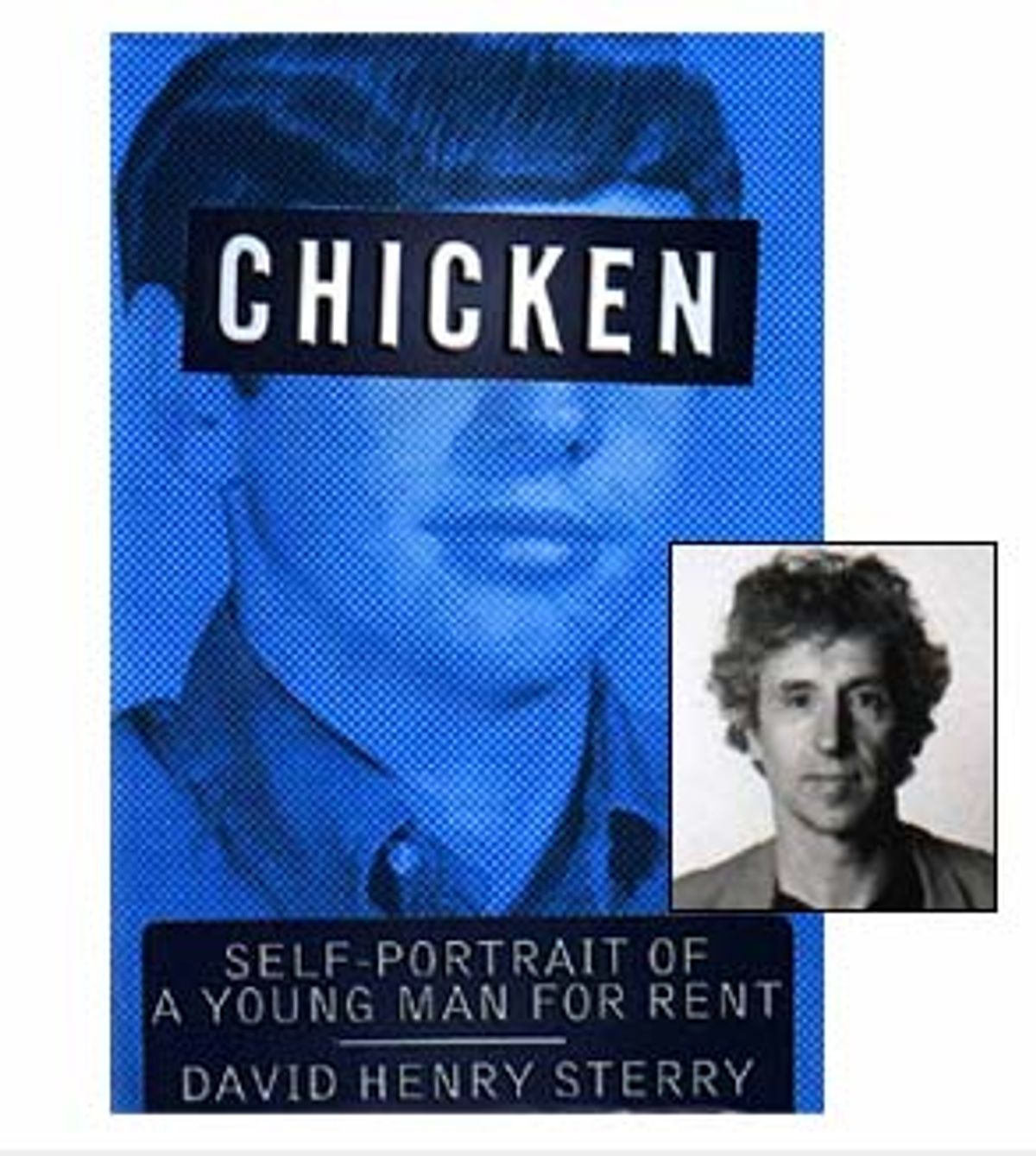

David Sterry is, among other things, a 40-ish heterosexual baseball writer coming to terms with his "inner ho." Satchel Paige is one of his role models and, last year, he published (with coauthor Arielle Eckstut) "Satchel Sez," a book about the pitcher's wit and wisdom. Sterry's idea of a religious site is Yankee Stadium. And he looks the part. Slightly gray, with a deep baritone speaking voice, he's what Americans routinely call "a regular guy."

At a sex-worker conference in May, I couldn't help noticing how unusual a "regular guy" can look in a room filled with male sex workers who are still acting boyish (even into their late 30s), and far more likely to be interested in gardening and decorating than baseball.

At first, it's disorienting to hear Sterry talking so candidly about the lost inner prostitute -- a youthful persona he left behind after a year of turning tricks while in college. He's not a veteran of the sex trade like some of us and he's new to the hookers movement. So Sterry probably has no idea what people are saying behind his back. Because most of his customers were women, he defies a few stereotypes, including those of the sex-workers' movement.

One male sex worker (who never met Sterry) suspects that he's "under-reporting the number of men he serviced." Come on, another activist insinuates, did he really make a living just doing women? Activist sex workers love to debate the authenticity of their comrades -- out of earshot, of course -- and we often theorize about whether or why a particular prostitute is essentially putting on airs. So Sterry is not being singled out.

In p.c. lingo, it's often stated that many males who have sex with men "do not identify as gay." The homophobic young hustler who resentfully has sex with men, while pretending that "nothing really happens" with his customers, is a trope -- of the sex trade, of the streets, of the movement. "But," I ask one doubtful colleague, "shouldn't you read 'Chicken' [Sterry's memoir] before you jump to all these conclusions?"

Sterry admits that male sex workers weren't the first people to welcome him into the movement. He sounds wistful. "They haven't been as warm toward me. But the women have been wonderful, very supportive." When I float the phobic-hustler-in-denial theory, he protests, "I'm not homophobic! I worked in the theater for 10 years -- and I was best man at my ex-wife's gay wedding." Despite his straight appearance, this guy is not exactly wearing the mantle of macho.

Hetero male prostitutes are sometimes treated like curiosities in our movement. At the PONY (Prostitutes of New York) meetings I attend, they are rare. When such a guy appears at a PONY meeting, the girls gather out of sheer nosiness. We ask questions that we wouldn't ask another girl, out of respect for her privacy. We sometimes end up sounding like the voyeurs we've spent our lives dodging. With all this in mind, I asked David Sterry for an interview.

I feel like we have so much in common! I had a feminist mom, like you, and divorced parents. We both did a stint at one of those experimental free schools. Started sex at 13. And then we became ... teen prostitutes. But here's where I start having second thoughts: The title of your book is "Chicken." You were turning tricks at 17. When I was a 17-year-old hooker, I thought of myself as a woman and if anyone had called me a chicken I would have slapped him! Isn't 17 kind of old to be calling yourself a "chicken"?

You may not have been a chicken at 17, but I certainly was. I didn't start working when I was 14, like you. At 17 I had had quite a bit of sexual experience, and yet in many ways I had led a life of sheltered affluence, wrapped in the suburban cocoon of my family. I saw myself as a man at 17, but unfortunately, I was not yet. I did not have the skills and tools to make my own way. I was taken advantage of because of my naiveté and ignorance.

So you didn't lie about your age? I worked in a nightclub at 15 where I was surrounded by hookers in their 20s. Those girls would have kicked me right out of there had they known I was so young.

I was hired by older women who wanted a teenage man-child, and that is what I delivered. I had the body, face and mind of a teen, not yet a man. To me, the whole point of chickenness is that it's that glorious in-between time when you're not a child anymore, but not yet an adult -- a teenager who engages in indiscriminate sexual activity for money. Tracy, I was so young and so tender. My pimp collected chickens, and I used to party with them, it was one of the great joys of my time in the Life. And believe me, I fit right in with all these beautiful young chickens.

I feel like I'm totally out of touch with teen prostitutes. I honestly don't know what I would say to a 16-year-old hooker if I met one today.

I do outreach with Larkin Street Youth Services in San Francisco, giving away condoms, lube and bleaching kits for needles, telling homeless kids about the health clinic and living facilities. We give out toothpaste, sunscreen, Handi Wipes -- the most popular item is Q-tips.

Q-tips! Really?

The kids can't get enough Q-tips. Also, because I discuss being raped and being a skanky ho, I have become a lightning rod for people confessing the horrible shit that's happened to them.

You dedicate "Chicken" to the "boys and girls who have been victims of abuse at the hands of adults." Did you really feel that your clients were abusing you?

I generally was not abused as a sex worker. One couple I wrote about in the book paid to humiliate me. I hated that. I was a terrible submissive.

I like the way you capture the teen hustler attitude --floating, aimless, "get the money up-front." But your female customers come across as individuals, which is very noticeable to me. I saw my customers as two-dimensional stereotypes back then. I didn't try to see into them the way you did. I didn't have to. I wonder if female customers work your emotions more. Was there any such thing as a stereotypical female client?

The only thing they had in common was that they had money and they were a lot older than me: traveling business ladies, rich lonely housewives, old hippies, kinky L.A. freaks, the newly liberated and the curious. I even had a grandma I worked with; she didn't make the book.

When you wrote "Chicken" did you see yourself as part of the "sex worker literati"? Did you think you'd be riding a cultural wave? Making a political statement?

I was a sex worker for one school year when I was 17, so I felt in many ways removed from the life. However, I was always drawn to sex workers after that, and had many friends in the sex-worker world. I felt compelled to write "Chicken" for deeply personal reasons. I wasn't even aware there was a "sex worker literati," so I feel lucky to be riding that wave as it's cresting.

The Sex Worker Art Show in Olympia, Washington, was the first event I performed in to promote my book -- in January -- and it was a life-changing event. The organizer, Annie Oakley, is one of the most amazing people I've ever met. I was overwhelmed by all the love and support people gave me. Being in that event allowed me to embrace my "Inner Ho" in a way I did not think was possible. And backstage: It's the only time I've been in a room where someone asked, "Does anyone have a spare nipple clamp?" and three people raised their hands and said, "Sure!"

Well, you went on to organize a number of sex-worker literati shows this spring on the West Coast. There's no convert like a recent convert.

And our next Sex Worker Literati event is in New York on Sept. 26. What I love about the shows is that they're a public forum to talk about sex and sexuality without anyone grinding their ax. So many times when I have been to meetings of people who have something in common -- like sex-worker conferences -- the interaction devolves into factions and personalities clashing. At the sex-worker literati shows, people are more interested in exploring the issues with the audience. They're sweet, touching, deep, troubling -- and I want to emphasize that they're always riotously funny.

Are there books or movies about male prostitution that strike a chord for you?

I did a TV show called "Mornings on 2," and they juxtaposed my interview with clips from "Midnight Cowboy." I love that movie, it's one of my favorite films, and it really seems to capture the damage, frustration and seediness of that world. "My Private Idaho" was very good. J.T. Leroy's "Sarah" is a beautiful book. "American Gigolo," on the other hand, is a joke. Believe me, Blondie was never playing in the background when I was working.

You mean, "Call Me"? I liked that song! So if someone makes a movie about your year as a teen prostitute, do you have a dream soundtrack?

"Get a Haircut" (and get a real job) by George Thorogood and "Mercedes Benz" by Janis Joplin would be on the list. Along with "Just a Gigolo" by Louis Prima.

You talk about being raped at 17 -- by a stranger and not by a customer -- in your first chapter. This isn't something I feel comfortable discussing or even reading about because I'm so squeamish -- and I was surprised that I could handle those passages. Are we in denial about male-on-male sexual violence? Are there some assumptions or taboos that make it harder for a man to press charges? I think a lot of women will ask: Why didn't you go to the police?

I think young men are not expecting to be raped -- I know I wasn't -- so in some ways they make easy targets. I believe I was drugged before I was raped, although I cannot prove that, yet I was so ashamed and felt so guilty -- like it was my fault -- that I did not report what happened to me. That is one of the great regrets of my life because I'm sure he did it to other kids. But I never wanted to see that guy again.

I think a lot of guys believe if they come forward, they will be labeled gay or that people will think they must have been looking for it. Someone in my own family said that I was stupid for going into that apartment, and that basically it was my fault for being raped. I was young and scared with no resources. I did not deserve or ask to be raped. I think very few men are willing to go in front of the world or into a court of law and say "I got raped." The first component of change is information. If people can look at me, a writer of books, married with a happy wife and life, maybe they can tell their own stories, and move through their trauma as I have.

Tell me about married life. Is it true that you recently married your agent?

Yes, I married the woman who was my book agent, Arielle Eckstut. I call her the Snow Leopard. She's beautiful, sleek, fast, delicate -- yet deadly when she has to be. She fired me as a client about a month ago and my new agent is the fabulous Mark Reiter of IMG. I love Arielle madly, and we have a blast working together. She's the one that told me to write a memoir in the first place.

I don't think I could handle having a guy in my life who is a symbolic sex worker, talking about all his former tricks. Do you think most women would agree with me? Or am I being a hypocrite?

I don't know how she does it. My ex-wife said that Arielle is part-saint, and that is accurate. She is an amazingly secure, open-minded woman. I think of myself as the poster boy for heterosexual, underage, male sex workers. Arielle is curious, smart and brave about my past. Again, she's the one who told me to write the book.

What are you working on, right now?

I am 50,000 words into a novel about a 25-year-old son who falls in love with his dad's fianceé. I'm trying to write this book with no sex in it, and believe me, Tracy, it's hard.

Shares