If you think drag queens give you a gender-bending, hocus-pocus, out-of-focus look at she-male chic, you haven't met Patty. Or rather Pat. I mean, Patrick.

Patrick Califia used to be a woman. The kind of woman that liked other women. But now she's a man. The kind that likes other men. Basically, what we have here is a carpet-licking lesbian who turned into a cock-sucking queer. It just doesn't get any weirder than that.

Actually, it does. See, Califia has a son, Blake, of whom he shares custody with his ex-girlfriend, Matt, who also used to be a woman, but is now a man. He stopped taking male hormones so he could give birth. They have no plans to write "Heather Has Two Daddies That Used to be Mommies."

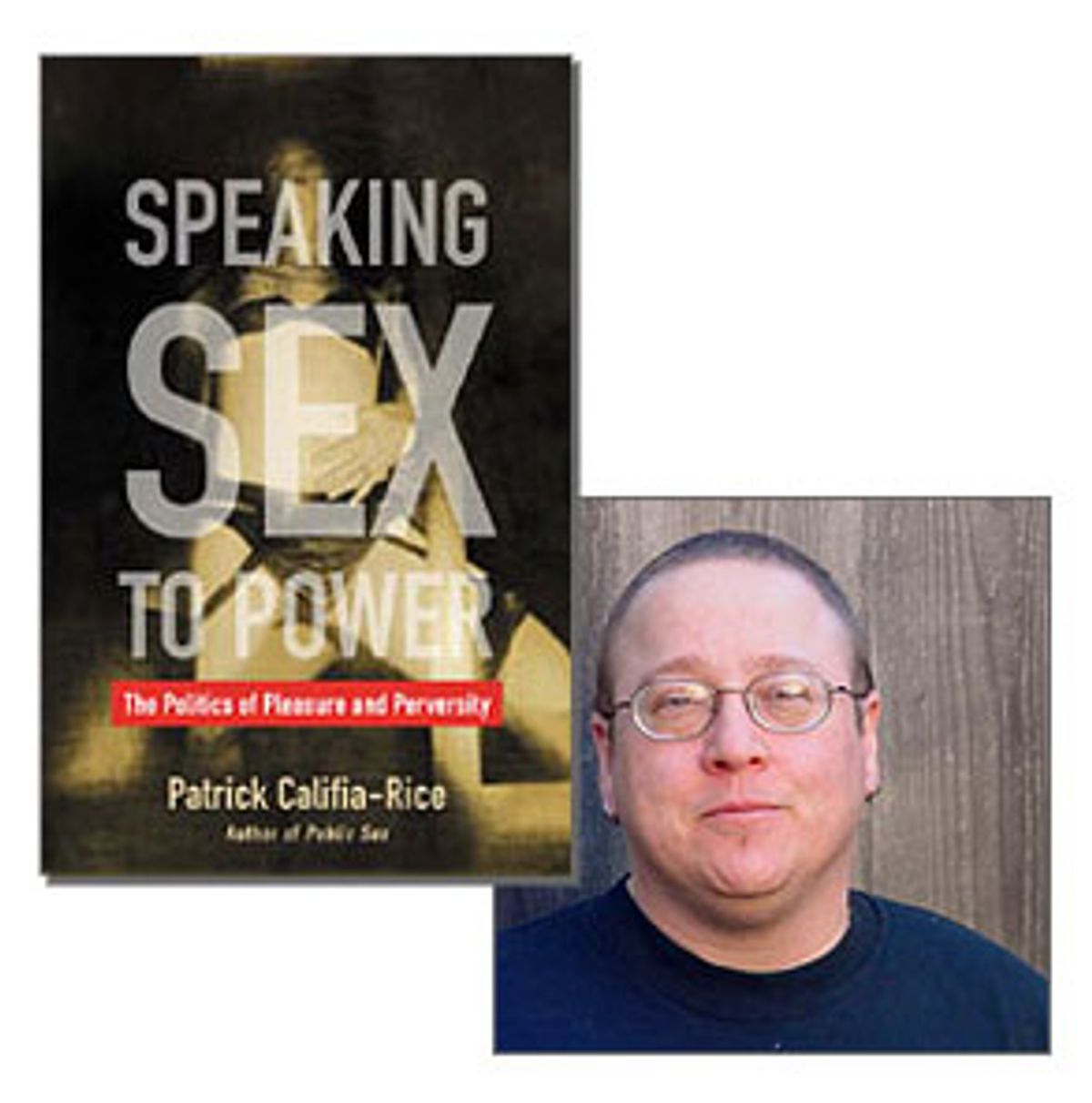

Instead, Califia wrote "Speaking Sex to Power, the Politics of Queer Sex." The book is a collection of essays spanning the last six years, include those written when she was a woman wishing she was a man doing a woman, and those written when he became a man wishing he had a dick to diddle other men while wondering if women found him attractive.

"I wish it were that easy to declare my allegiance to one gender paradigm," Califia writes. "... And to climb up on only one soapbox in the orator's park of sexuality ... There are days when it seems to me that I am tortured by my own perversity and willfulness, that if I had the right sort of subtle knife, I could sever the carping parts of my soul that will not shut up and could quit setting off the security alarms of normal people."

Califia has a lot to say about gender identity that's worth hearing. Like his idea that identity is not "just a matter of who believe yourself to be. It is also affected by how others perceive you ... Identity has a public sphere."

Yet there's something a little annoying about Califia's demand to be called whatever he feels like being called, regardless of his anatomy. He's like a bush resenting the grass for not calling it a tree. Well, if you've got a bush and no trunk are you really a tree?

Califia argues yes -- that gender is a state of mind more than it's an observation of fact. And he does an admirable job of putting forth unique theories of identity. For instance, his contention that "Socially conditioned behaviors that signal gender are even more crucial than physical traits." In other words, the way a woman is conditioned to dress, walk and behave is often seen by society as a better marker of her femaleness than her sex chromosomes, secondary sex characteristics or genitalia.

Unfortunately, Califia has a way of tossing out verbal bombs that diminish his credibility, and credibility is something he needs desperately if his more cogent observations of gender identity are to gain credence. Califia writes, "Like camp, promiscuity is the pink badge of queer courage, our defiant way of whistling past all the graveyards that, for us, dot the heterosexual landscape." Oh, please. Promiscuity as a badge of courage? My sex advice column has generated countless letters from gay men; I've never been asked how they can change their political viewpoint so it could lead to a more monogamous sex life. Only an activist can ascribe political motivation to plain old dog-yard scrumping.

Or take this gem: "Every cocksucker is well aware that the same man who puts on a badge to arrest him probably just gets his blowjobs at a different truck stop." Typical loudmouthed gay activism: Everyone's gay; they're just closet cases.

Califia's writing is infected with "activistitis," the idea that your political spouting is more interesting than your personal story. And his propensity for picking a fight instead of revealing his character can be exasperating. For example, he writes, "Does the fact that I am taking testosterone now and asking everyone to refer to me as 'he' invalidate the years of my life from age 17 until 45 when I was out of the closet, first as a dyke, and then as a bisexual woman?" Then after striking a pose as a lesbian, bisexual, transgendered, S/M dominatrix, she strikes one as victim: "I am to be hissed at as a deceiver, a traitor. Everything I have ever said or published about feminism or lesbianism must now be tossed on the bonfire. Every woman-identified woman I ever had sex with must move the memory of that liaison into a dubious category, and purge herself of possible heterosexual contamination. Well, it's no less than what I expected."

Another disappointing part of the book is the absence of pictures. This undercuts Califia's claim to be a sexual outlaw. Since when are radicals afraid to show their faces?

It's understandable to think that pictures might lend a circus atmosphere to the sober tone of his subject, but by not providing pictures Califia lets the rhetoric float in an intellectual surface without ever descending into the emotional realm, where understanding and acceptance take place.

Yes, it would be shocking to see a busty leather dyke morph into a flat-chested, hairy gay man, but shock is always the initial reaction to the different. Would "Will and Grace" have broken down barriers if it had been a radio show? Califia, the audacious fire-breathing dragon-activist is a closet-encrusted prude. Come out, come out, Patrick, wherever you are.

Califia is at his best when he bares his soul instead of his fangs. It's hard to ignore his humanity when he writes, "Compassion for myself has been at least as healing as daily application of testosterone gel to my fuzzy belly, chest, and face. I know that I deserve to have pleasure in my life even if my body puzzles and thwarts me."

And his love for his son, Blake, is palpable: "Love for a child may be the most all-encompassing emotion that I have ever experienced. You cannot break up with your child or divorce him. When adult lovers have left (or, more typically, been sent away), I usually experience more relief than sorrow. But the love I feel for Blake is not susceptible to alteration, no matter what he might do in the future or whom he might become. I could not escape from it if I tried. And in truth I do not want to, because the weight and scent of his little body in my arms has made me his happy possession."

Although it's heavy on the irritation factor, this book is a must-read for anyone who has ever experienced the torture of being different, of not belonging. Califia has a deft way of both eulogizing and celebrating otherness. "The only consolation for this sense of alienation," he writes, "is the fact that there's no place where I don't belong. Having shed most of the strictures of identity politics, I can take what I like from the entire spectrum of sexual minority cultures."

Shares