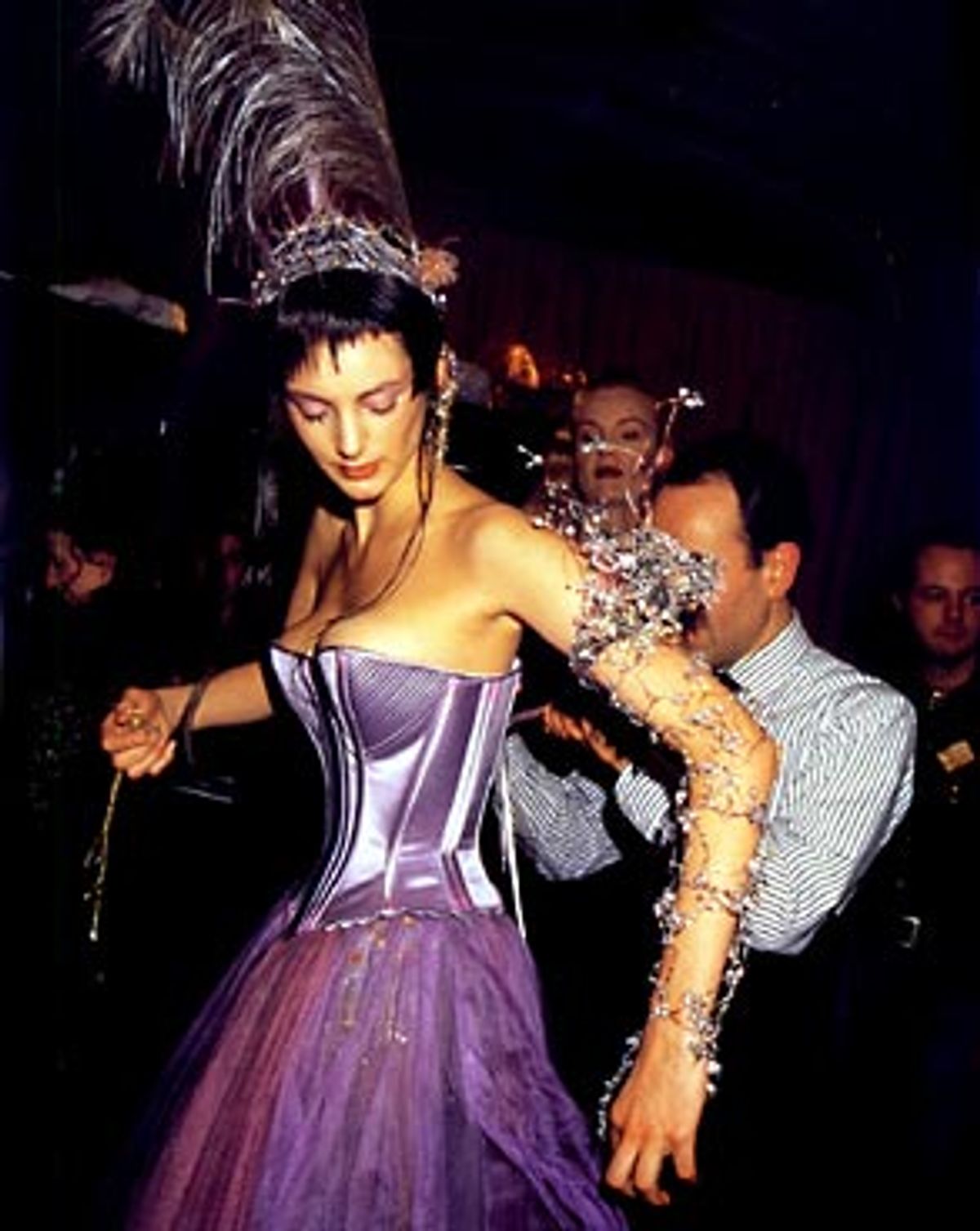

The corset is to nudity what foreplay is to sex. No other garment is so erotic because none has as loaded an effect on the female form. And few garments are so controversial; every century attacks it and appropriates it anew.

What was once the argument of the gentleman misogynist is now the line taken by the academic feminist: The sexual body is a dangerous thing, best shrouded from sight. That's the line taken in a new book by feminist scholar Leigh Summers, "Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset," an examination of the garment's "role in female objectification" originally written as her doctoral dissertation. In her introduction, she claims that "[t]he corset remains profoundly under-theorized." She then goes on to build a theoretical construct similar to that advanced by those 19th century men who, in the name of morality, sought to suppress women's sensuality.

While her mind is perhaps slightly sounder than that of Victorian phrenologist Orson S. Fowler -- who warned that wearing a corset excited dangerous "amative desires" by pressing blood to bowels -- her reasoning is largely consistent with that found in such chauvinist classics as "From Ballroom to Hell" and "Where Satan Sows His Seed." Plus, she uses language like "hetero-patriarchal dominance."

The legendary British sexologist Havelock Ellis described the corset's physical allure more anatomically. He said that it "furnish[es] woman with a method of heightening at once her two chief secondary sexual characteristics, the bosom above the hips and buttocks below." Yet his words give the impression that it was an ingenious invention -- a sudden fancy -- rather than the result of a gradual evolution in dress. Stays became technically feasible only after centuries spent hemming in clothing to fit the body more closely, revealing with ever greater candor the contours particular to each gender. If the first step in human modesty was the fig leaf, the corset stands as the crucial leap back into the suck of desire, the long-overdue renewal of animal instinct that gives life its vigor.

The trend toward tighter garments is in evidence as early as 1244 when Leonor, Queen of Castille, was interred in a gown bound with laces. But it is a mistake to assume that, even then, the pleasure of a better fit was exclusive to women. While the costume appropriate to each sex became increasingly distinct, both benefited equally from advances in tailoring. Doublets and hose become de rigueur for men, while women wore bodices of cloth or leather. By the 1500s, when men were wearing codpieces to complement ever-tighter tops, fashionable women could have whalebone stitched into the fabric of their "bodyes," stays to shape the waist and a busk up the front to keep the carriage erect.

The effect, as might be expected, was to bring sexuality out of the private sphere into the realm of social intercourse. By accentuating those attributes specific to men and women, clothing could become more revealing without affording significantly less covering. While actual exposure of the flesh would never have been permissible in Elizabethan England or the Italy of the Medici, denuding clothing offered an apt surrogate.

The result, of course, was outright objectification -- of women, and also men. After centuries of disembodied religion, Western culture rediscovered its humanity, the physical fact of life on earth. Even at the height of Victorian propriety, the corseted body endured as a visceral reminder of our underlying nature. One can understand why phrenologist Fowler and his set would want to forget that women, like men, are made of flesh: Suppressing women begins by killing in them what is most uncontrollably human, the "amative desires" that he rooted in pressure on the bowels, and presumably perceived in the allure of every perfected curve.

What makes less sense is why the academic feminist orthodoxy also would want to keep the feminine body hidden from view, and female sexuality under wraps. Objectification of others isn't evil. On the contrary, it's a step in the direction of honesty about ourselves. The appearance of bodice and doublet in the 14th through the 16th centuries represents a first important break from the shackles of civility, a leap toward the individuality we now each enjoy. Women can today be more fully women, men more fully men, because secondary sexual characteristics are not shrouded in shame. Far from an article of bondage, the corset has been an instrument of liberation.

The most compelling case Summers makes against the corset is also the most typical: Like Fowler before her, she appeals to the corset's ill effects on women's health. Others have been more encyclopedic. Perhaps most extreme of all was Luke Limner, in whose notorious 1874 polemic, "Madre Natura versus the Moloch of Fashion," can be found reference to diseases caused by corsets ranging from apoplexy and asthma to hunchback and hysteria.

Recently fashion historian Valerie Steele published her impressively balanced, if improbably bland, "The Corset: A Cultural History" in which, together with cardiologist Lynn Kutsche, she offers a long-overdue reconsideration of the medical evidence marshaled by Limner, Summers and others. She does so with good reason, recognizing that medicine in the hands of a man like Fowler was wielded as a rhetorical tool, and that science in general is only as reliable as the prejudices of the day. Steele sagely points out that "[h]istorians who would never accept medical accounts of the dangers of masturbation (that it causes blindness and insanity) or female education (that it sucks the blood from the uterus to the brain with appalling results) become perversely credulous whenever fashion is the subject of medical anathema."

In the present case, they tend to conflate two distinct practices: corseting and tight-lacing. As a physical feat, tight-lacing is astonishing, easily in the same league as contortionism and sword-swallowing. The practice of lacing a corset progressively tighter, worn day and night, to reduce a 22-inch waist to 12 inches was, and remains, a fringe activity. To disparage it is one thing, but to consider the risks taken by tight-lacers equivalent to those taken by ordinary fashionable women is about as reasonable as assuming that normal use of silverware endangers the digestive system to the degree of a swallowed saber or machete.

A survey of surviving Victorian stays shows that, while corseting was almost ubiquitous, few women could plausibly have even attempted to achieve what was popularly known as a "wasp-waist." Organizing an exhibition several years ago for the Fashion Institute of Technology, Steele found that corseted waist-hip ratios tended toward .72 which, far from freakish, approximates the natural build of everyone from Kate Moss to Marilyn Monroe, Twiggy to the Venus de Milo. With good reason: A 1993 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found consensus across ethnicity and gender for the desirability of approximately that ratio, numbers that typically indicate high fertility. So those secondary sexual characteristics admired by Havelock Ellis incite passion at a basic biological level, the level at which we objectify, at which we are objects of one another's desire -- the point at which basic procreation takes place.

Yet, even if we can see why tight-lacing was never prevalent, we may wonder why the practice was so infamous. What we need to understand is that, like any fetish from sadism to masochism, notoriety is inversely proportional to occurrence. Quite simply, the extraordinary makes an alluring story, whereas the commonplace merely makes a sound statistic. A publication such as The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, widely circulated from 1867 to 1874, is of interest to Leigh Summers for the same reason it attracted such a broad audience initially: Accounts of systematic slimming of 1 inch per month are sensational, even if not necessarily true.

Then what were the health risks to the average woman? Observing the effect of the garment on present-day enthusiasts and reviewing available evidence in Victorian medical journals, Steele and Kutsche make a compelling case that "from the perspective of modern medicine, corsets were extremely unlikely to have caused most of the diseases for which they were blamed." Conditions such as scoliosis were probably helped, in fact, by the support the garment provided, while others, such as breast cancer, became no less common as corsets went out of fashion. While pressure on the liver likely altered its shape, that would not have meaningfully altered its function, and reported deformation of the ribs might as likely have been caused by rickets. Even more plausible claims, such as the risk of damage to the reproductive system, are difficult to assess; while more women suffered from a prolapsed uterus then, that may just be because multiple pregnancies are no longer so common.

Perhaps the favorite myth of the 19th century anti-corset brigade was that stays caused consumption. While long ago dismissed -- the fatal lung disease is actually induced by the tubercule bacillus -- the theory continues to capture the imagination of academic feminists like Leigh Summers. More generally, Summers is obsessed with the relationship of the corset to swooning, fainting and "the construction of a morbid female sexual subjectivity." It is her contention that the perceived connection of the corset to death by consumption is indicative of male idealization of submissive women, and that there is something sadistic in men's appreciation of breathlessness caused by the corset.

Nobody would claim that corsetry lends a healthy appearance to the female body. By shortening the breath, stays cause the breasts to heave, and give the skin a pallor described by one 19th century doctor as "softly shaded by melancholy." And unquestionably a look of fragile health was then admired by men: Edgar Allan Poe deemed female death "unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world," and, as if to illustrate, Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote of his desire for "a woman as true as Death. A woman, upon whose first real lie, would be tenderly chloroformed into a better world."

Such sentiment is lost on Summers, to say the least: She accuses Holmes of "murderous and almost necrophiliac fantasies," condemning Victorian society collectively for its "macabre, misogynist values." Willfully misinterpreting the spirit of the age, she gives the impression of evil intention in the marriage of romance with death.

Pity her insensitivity: Death is, and always has been, hopelessly romantic. Were it not the natural complement to love, we wouldn't be able to understand Greek tragedy, let alone appreciate Chaucer, Shakespeare or Goethe. Nor would we enshrine John Keats -- never mistaken for a woman -- for the consumption he suffered as much as for the words he wrote. Just as entrances and exits are singularly dramatic in theater, love is most palpably alive, sex most alluring and romance most robust, at the beginning and at the end. The fragile balance evoked by Holmes isn't misogynist (it would work as well were the subject male), nor is it necrophiliac (it wouldn't work at all were the subject deceased). The image is potent because potential loss makes us realize how much we have, entices us to recognize its worth. Nothing is so lively, so lovely, as deathly pallor: Embracing the body, the corset frames a story to stir the emotions and set the imagination free.

Shares