With the Beijing Olympics about to begin, we turn our attention momentarily to games from almost half a century ago. Pulitzer Prize-winning writer David Maraniss, author of sports biographies of Roberto Clemente and Vince Lombardi, has a new book called "Rome 1960: The Olympics That Changed the World."

As you'll hear Maraniss admit in the accompanying podcast, the 1960 Olympics didn't really change the world, but they did reflect the rapidly evolving times. Many of the issues that are familiar today were new in 1960.

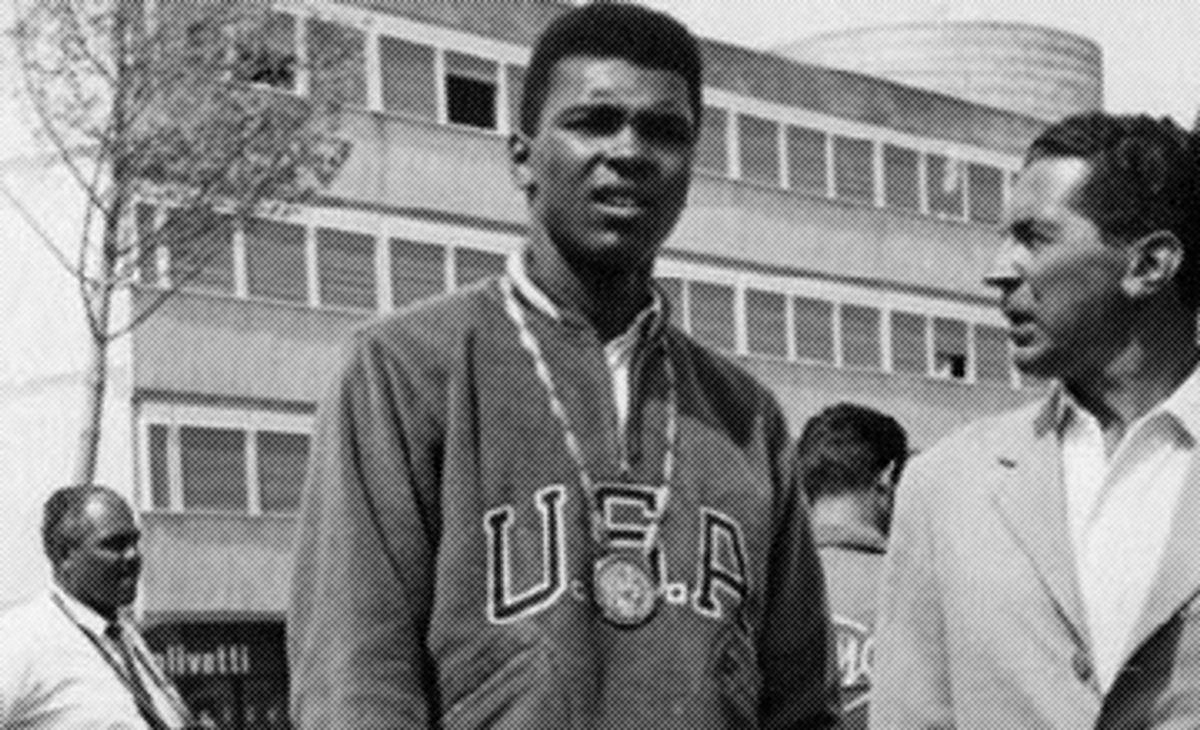

Cassius Clay, not yet Muhammad Ali, in Rome. Listen to the interview with David Maraniss

The Rome Olympics were the first to be televised, the first with a doping scandal, the first in which a black African, marathoner Abebe Bikila, won a gold medal. An 18-year-old boxer still named Cassius Clay wasn't yet a star, but it was in Rome where he stepped onto the world stage, four years before renaming himself Muhammad Ali.

The American flag-bearer was Rafer Johnson, the great decathlete who represented a country that didn't afford him full civil rights back home. The International Olympic Committee, claiming to be apolitical, refused to listen to complaints that the all-white South African team was the result of discrimination against that country's black athletes. Four years later, a threatened boycott by black African nations forced the IOC to ban South Africa.

I spoke to Maraniss, who was on a book tour in Clay's hometown, Louisville, Ky. He'd just gotten back from the Muhammad Ali Center. Here are highlights of our conversation, more of which is included in the audio clip.

The thing that interests me about the connection between the 1960 Olympics and today, or any Olympics, is this whole idea of the Olympics as being above politics and above the fray that the IOC has been talking about for almost a century now. That really played out in some fascinating ways in 1960. What was the most interesting to you, the Cold War, the African nations?

It was everything, it was the whole world actually, with a Cold War overlay to all of it to some extent. Since we're approaching the Beijing Olympics it's interesting to note that it was exactly 50 years ago in 1958 that China withdrew from the Olympic movement because of the presence of Taiwan. You know, their mortal enemy.

And then before the 1960 Rome Olympics began you had Taiwan being urged by the right wing in the United States to boycott the Olympics because the International Olympic Committee had ruled that they had to call themselves Taiwan or Formosa and not the Republic of China. So they actually walked into the Opening Ceremonies carrying a banner that said, "Under Protest," and did not boycott mainly because they had one great athlete, C.K. Yang, who was going to win a medal for them. So you had the two China issues boiling over and coming right into the Olympics.

In black Africa you had 14 new nations being born that year but also the IOC refusing really to deal with the blatant racism of South Africa still, which was a complete breach of the Olympic creed, and buying the argument in 1960 that the white South African Olympic committee made that they weren't discriminating, there just weren't good enough black athletes.

In Europe you had [East and West] Germany competing as one team even though they hated each other's guts, which was an effort by the IOC to sort of say there's no politics here.

I tend to think that the politics and the sports are inseparable; they go hand in hand in every Olympics. But you can still enjoy the sports and just acknowledge that any time you have the entire world on the same stage at the same time there's going to be a lot of politics involved too.

You had the Americans and the Soviets going for every little propaganda edge they could get. That kind of competition, it's weird to say, but that's kind of missing today. There's now a whole generation of grown-ups who never experienced that U.S. vs. Soviet Union thing.

It's like you have to have the Yankees to root against. It's that same mentality for sports, and it also has the added dimension of being political too, although I think it was really more that just because of that, you need somebody to root against for your own team to give it the full flavor.

But I think that you might see some of that in Beijing actually with the Chinese. They're sort of emerging as the villain, in a sense, or at least the antagonist.

The book's subtitle is "The Olympics That Changed the World." First of all, is that your title or the publisher's?

No. Thank you for asking! Because a few of the reviewers have just snatched onto that subtitle and strangled it. The point of the book is that at these Olympics you could see the modern world coming into view, for better and worse. That's really it.

My point is that whether the Olympics changed the world or the world reflected the Olympics or any of that, it's just that here's a really interesting point of transformation. When you think about what's going on today, with doping, with television, with the excess of commercialism, with all of that, where did it start? And you could see the roots of all of it in Rome in 1960.

And on the positive side you could also see the start of advancements for women and blacks.

How did you come to this book? At what point did you say, "Yeah, 1960 is what I want to write about"?

I came to it completely by accident. I was researching my last book, on Roberto Clemente, and his first great season was 1960, when the Pirates won the pennant and the World Series.

So I was looking at all these old sports sections in August and September of 1960, looking for stories on Clemente and the Pirates, and I kept coming across these incredible names: Rafer Johnson. Cassius Clay. Wilma Rudolph. Abebe Bikila. Jerry West and Oscar Robertson. And I really couldn't get the names out of my head, but I wasn't thinking about a book at all because I didn't think my next book would be about sports.

And then as I looked into it a little further I saw all these other things, that it was the first televised Olympics, that a doping scandal, a death, occurred there. I didn't have to force the context that the politics of that moment flowed through the Olympics. So I just went at it.

I like how you kind of pointed out early in the book that, when you say Rome 1960, people today say, "Oh, Muhammad Ali. Cassius Clay." We have to get out of the way: He was a minor figure. He was there and he won a gold medal but he wasn't yet --

And here I am in Louisville talking to you about it. I was just at the Ali Center, actually. No, I mean, he's an interesting character in the book, almost comic relief, but not the central figure, certainly not of the American team. Wilma and Rafer Johnson were far more respected among their peers. Cassius Clay was only 18 years old. He sort of was tolerated, sort of like a bothersome little brother almost among the other athletes.

Rafer Johnson is kind of the towering positive figure of the book.

I would say that that's true. He was a great athlete, he's just a beautiful man, still; he looks like he could win the decathlon tomorrow and he's 72. And he's incredibly smart and gracious and not at all full of himself and never has been. Because he's somewhat quieter and not as egotistical as a lot of athletes, it's harder for him to get his due, I think. So I wanted to give him that.

Another towering figure of the book, not in such a positive way, is Avery Brundage, the IOC chief of the time. He really comes across as kind of a hypocritical boob. I think I'm getting too cardboard of a picture when I say that. He did some good things. Or did he not?

Yeah, he did. He did some things that were so horrible that it colors everything about him. But to give him his due, I would say that he really helped hold the Olympics together during the very difficult decades in the middle of the 20th century. It wasn't an easy task.

And he did hold up the standard of the Olympic ideal, even if he broke it himself. At least that was his obsession, and that was not a bad thing. So in those ways I think he was a positive force. But his anti-Semitism, going back to 1936, completely overshadows anything else good you want to say about him.

I mean, [consider] the letters that I found of him writing to the German officials in 1936, saying there's a lot of bad stories coming out of Berlin these days, why don't you send me some clippings about all of the good things Hitler's been doing.

His notions of amateurism, while you could hold them up as the Olympic ideal of purity, they were imposed by people like him. You know, millionaires and royalists. Most athletes come out of poverty and hunger, so it's a very different thing for them. It's easy for rich people to say they should never take money for that.

Shares