"Gimme 50 cents! Gimme 50 cents!" Goboy says. "I say gimme 50 cents because God says gimme 50 cents!"

If you ever have the chance to get to one of Frank Garvey's performances, it is likely that the first thing you will see, even before you get through the door, is Goboy. Depending on your convictions about panhandling in general and panhandling by machines in particular, how early or late you are to the performance, and -- in Garvey's own view -- your class and degree of class consciousness, you might try to ignore Goboy or to interact with him, and either way you are likely to come out frustrated.

Being a machine, or more precisely an anthropomorphic sculpture of menacing and derelict clay mounted on the chassis of a motorized wheelchair, Goboy can beat you in both speed and patience. As a remote-controlled machine managed by an experienced handler, he can generally outwit you. If you try to brush past him, you might find him rushing toward you at unnerving speed. If, on the other hand, you gamely try to drop some coins into his hand, he will simply continue haranguing you for more.

There is no easy solution to the problem of Goboy, except finally to rush past and move on into the theater, carrying with you a vague and unresolved feeling of discomfort. Like all the robots designed by Garvey and his robotic theater troupe, Goboy is extraordinarily discomforting. The same goes more generally for every aspect of Garvey's work. It is confrontational, it is political; it is, as Garvey's own manifesto points out, fiercely Marxist in spirit, and yet the strangeness and intricacy of the machines at its heart make it irresistibly seductive.

Schooled in painting and electronics, Frank Garvey is an artist who has chosen as his form the production of robots and their deployment in increasingly complex multimedia performances. "Multimedia performance" does not really do justice to Garvey's theatrical and musical productions, but it is probably the best word in the contemporary vocabulary for what Garvey creates.

Since 1995, Garvey and the San Francisco theater group he directs, Omnicircus, have staged a series of plays and less elaborate musical showcases that do not resemble anything else in contemporary art or performance. They can, depending on one's mood and the background one brings to them, recall the abstract pessimism of Beckett's "Endgame" or the gothic overripeness of Siouxsie and the Banshees. What distinguishes them from everything else, however, is the machinery on which Garvey and his associates have expended years of labor.

The machines that Garvey has built on his own represent a cross-section of the urban demimonde. It's a vision with a history that stretches from the London of William Blake's "Songs of Experience," with its harlots, bloody walls, and menacing soldiers, to Charles Bukowski, bard of the down and out. In addition to Goboy the panhandler, the assembly of robots has included "Humper," a once disassembled and now effectively deceased robotic prostitute; "Preacher," a loudspeaker mounted on a metal carapace that rolls around on a four-wheeled platform; and a half-dozen others. Most of Garvey's designs combine mechanisms constructed to emphasize the crudeness of welded metal with abstract organic clay forms that bring to mind fire-blackened bone. All share what Carl Pisaturo, a member of Garvey's group and himself a designer of robotic assemblages, calls "a rusty-metal aesthetic" -- a general aura of menacing industrialism.

Garvey has teamed with collaborators to build even more complex robots. "One-Legged Men at a Butt-Kicking Contest" (the image is taken from a scene that recurs in Garvey's paintings) is a human-sized assemblage he built with fellow robotic artists Jeff Weber and Aaron Edsinger. The result is two crane-like constructs which heave at each other with amazing speed in a barrage of blinking lights; the carefully programmed and choreographed battle brings the sensitive mechanical parts this close without actually making contact.

All of this is supremely entrancing, and it is clear from the mass of digital cameras at an Omnicircus performance that it is the robots that have pulled the audience into the theater. But here is the frustrating, maddening and troubling part of Garvey's art: The audience never gets to see enough of the robots, which are often offstage. As you might have guessed when you were confronted with Goboy, Garvey's ensemble of robots are players in a larger project of social criticism, to which he expects his audience to devote its undivided attention.

This fall Garvey is leaving San Francisco for Pittsburgh, where he is about to begin a one-year fellowship in robotic art at Carnegie Mellon University. In preparation for his departure, Garvey and DeusMachina, the musical group associated with Omnicircus (Garvey composes the music), have staged a kind of farewell performance. As striking as any part of the performance proper is a pre-performance, an introductory lecture that Garvey gives to his increasingly discomfited audience.

Garvey, a short, powerfully built man in black denim with a gray goatee, strides to the stage and tells one of his favorite stories, about Nelson Rockefeller and the mural he commissioned from Mexican artist Diego Rivera to decorate the newly built Rockefeller Center. Seeing that the mural was an attack on the barbarisms of capitalism, Rockefeller immediately ordered it destroyed. In his story, Garvey visits Rockefeller Center to inquire about the mural, only to be informed, finally, that "The mural doesn't exist because Mr. Rockefeller never accepted it." (Ironically, Garvey owes his own fellowship at Carnegie Mellon to a new industrial titan: Microsoft is underwriting his grant.)

Garvey's lecture builds to a crescendo of protest against the evils of capitalism, ending finally with a proclamation: "I will not start this show until someone gives me a definition of ownership." The members of the audience, or at least those who have not seen this before, look at each other uncomfortably. To get to Garvey's theater, they have ventured into an inhospitable back alley of San Francisco's downtown, past rows of steel-grated flophouses, hoping to get a peek at the extraordinary machines designed by Garvey and his Omnicircus performance group. Yet here they are, being told that the show will not go on until they, the audience, demonstrate an ideological interest in the material -- what the Old Left would have called "engagement."

When I heard Garvey's speech, I believed that I understood the kind of engagement that Garvey was looking for -- understood, so to speak, where the battle lines were drawn. On one side was Rivera, the painter, and Garvey himself, a committed Marxist. On the other was 20th century industrial capitalism, represented by Rockefeller, one of its iconic figures. There was no doubt in my mind that Garvey placed the machine on the wrong side of the equation, together with Rockefeller.

Several days after the performance, I presented this idea to Garvey himself, and he neither confirmed nor denied it. He listened carefully, almost clinically, clearly interested in the reaction his work elicited, but he gave the altogether reasonable response that he did not believe that artists should answer such questions about the meaning of their work.

You can call the interpretation that I presented to Garvey the "machines are bad" view of his art. It is likely that this is the theory that most of Garvey's audience members take home with them. It certainly appears to fit nicely with Garvey's politics: Machines are bad because they represent the dehumanizing influence of industrial capitalism -- with Goboy, the very picture of resentful, machine-bound poverty, as the prime example.

In 1998, I saw another production of his work, a play called "Sermon on the Mound." "Sermon" was a play that used a large number of robots and one human actor. It took place, apparently, in a post-apocalyptic netherworld. The actor strutted up and down the stage, dressed in a long, dirty canvas robe, his arms tied at his sides. Preacher, the robot with the megaphone, came out to give orders and spin around in a lunatic fury at the front of the stage. The human character was in some way indebted to Preacher, with whom he would plead and remonstrate. This by no means sums up the technical accomplishments of the play -- it is really little better than describing a painting -- but it suffices to give you a sense of the plot. At the end of the play the actor collapsed, leaving nothing on stage but the One-Legged Men in a Butt-Kicking Contest, who came to life and proceeded to kick each others' butts into kingdom come. Bad machines, outlasting the poor saps who'd built them. It all comes together with the pleasant patness of an undergraduate thesis on Bertolt Brecht.

There is, however, one big problem with this "machines are bad" interpretation. If you happen to speak directly with Garvey about his view of the future of machines, you will find that at times his view is actually blithely utopian. In good Marxist terminology, Garvey will argue that industrial society must either exploit labor (as he believes it is doing now) or -- and this is a crucial "or" -- exploit technology. "The alternative to slavery" -- Garvey's catch-all term for industrial capitalism -- "is robotic civilization," he argues. He then describes a possible future in which, put simply, robots do all the work. When he says things like this, Garvey sounds as optimistic about technology as the most starry-eyed George Gilder-quoting futurist.

When I heard this coming from Garvey, I could not make anything of it, so contrary did it seem to the tenor of his art. I simply could not understand what would make his annihilating criticism of industrial society fade into techno-utopianism when the subject turned to the future of machines. Garvey's optimism was a nut I couldn't crack.

That's when I spoke with Carl Pisaturo.

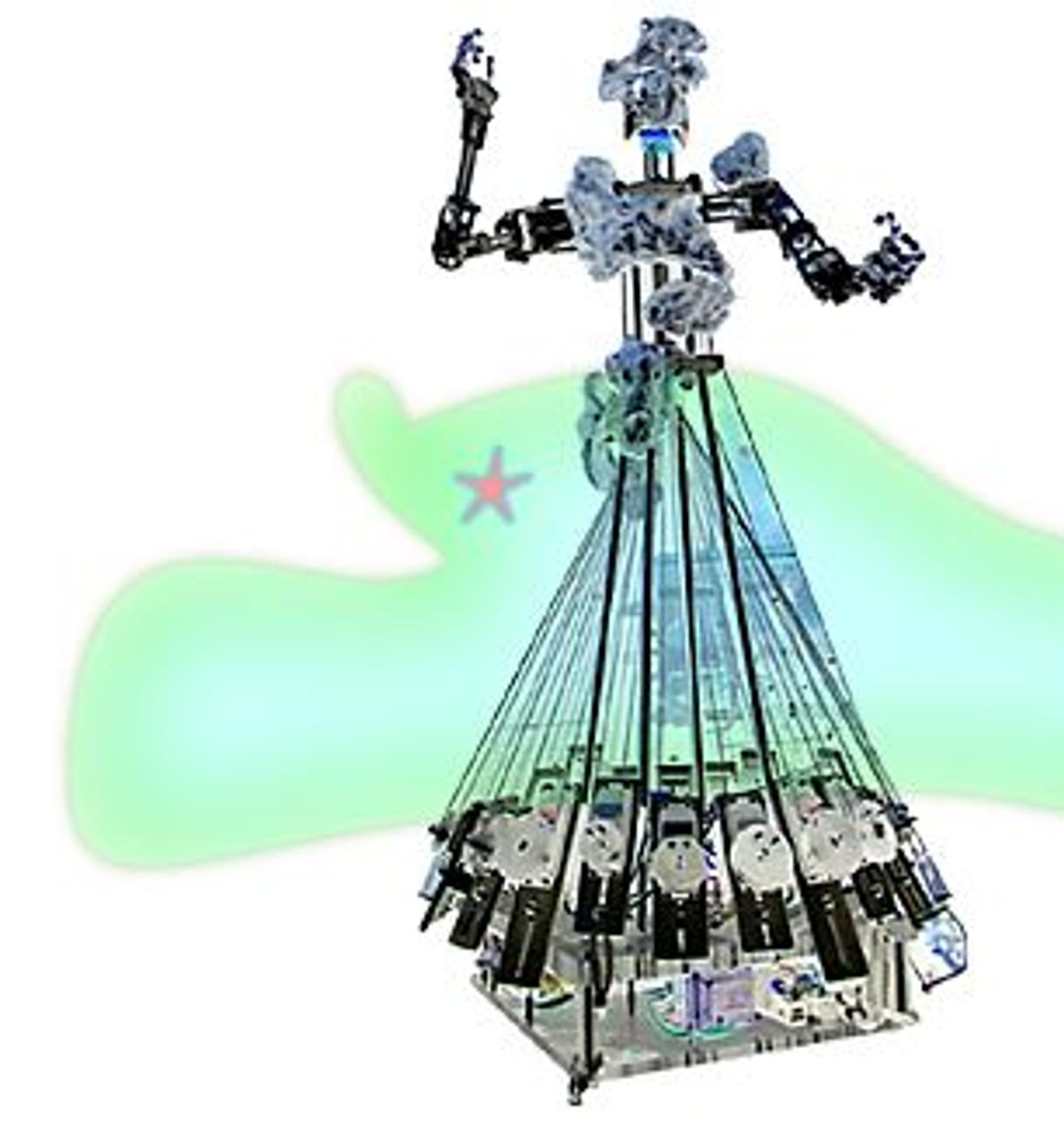

Pisaturo is one of Garvey's closest collaborators. Like Garvey, he lives in a tiny loft in the Omnicircus theater. Pisaturo built the mechanisms at the heart of two of Omnicircus' smallest and most complicated robots, "Slave Zero" and "Slave One." When you first see them, Slave Zero and Slave One are almost disappointing. Their design recalls a human torso mounted on a triangular base. Like all the Omnicircus robots, their mechanism is intertwined with black clay. Only their arms and upper torsos move, and they look relatively unimpressive until you look at them closely, and realize with a shock that not only their arms but each individual finger is fully articulated. Pisaturo's technical drawings for the two robots, accompanied by carefully pasted photographs of every part, take up a notebook as thick as an encyclopedia volume. Each of the robots boasts some 45 movable joints, controlled by 21 separate engines. It is when you realize this that you sense that they are unlike anything you have ever seen.

I asked Pisaturo what the machines represented. Pisaturo had already told me about his admiration for great feats of engineering. Among his influences he had named the Hoover Dam, the "Pirates of the Caribbean" ride at Disneyland and the fully automated cigarette factory he had toured at the age of eight. Still, I expected Pisaturo to tell me that Slave Zero and Slave One represented a kind of fall from the perfection of the human condition.

"It's a beautiful machine," Pisaturo said instead, "overlaid by a distorted skeleton."

It was then that I realized that, like me, Pisaturo -- and quite certainly Garvey too -- was entranced by the machines, only many times more so. It is this fascination that makes the messages of Garvey's work intuitively cryptic, equivocal and disturbing. An artist who works with machines can be a Marxist, but he cannot be a Luddite. The allure of the beautiful machine is far too great to be easily shaken -- especially by its builder.

Shares