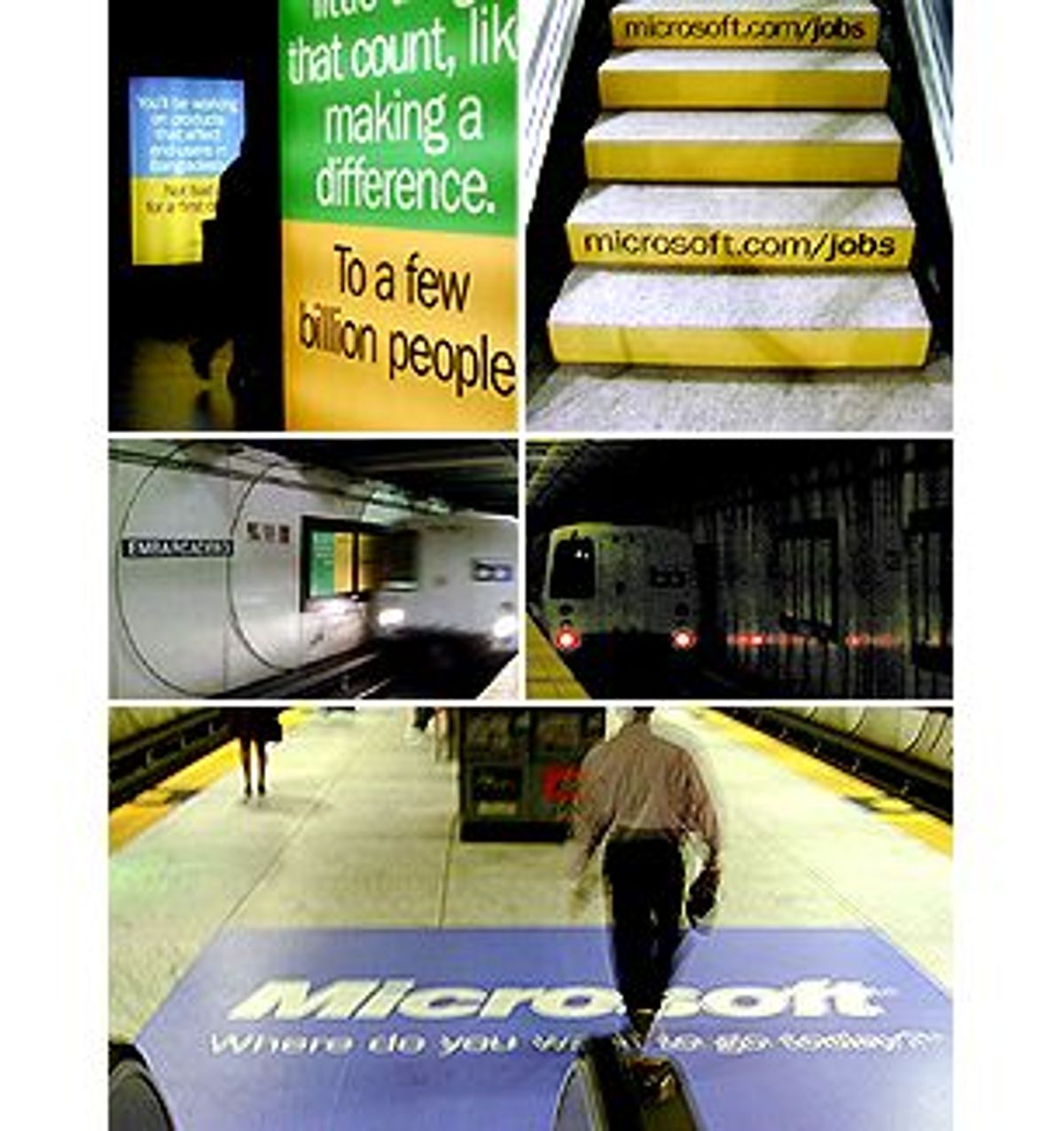

"You could spend your whole life trying to change the world." The ponderous message looms above hordes of commuters descending into San Francisco's Embarcadero station. As the escalator coasts towards the train platform below, an overhead banner hung from cement rafters continues the barrage: "No, seriously. You could."

By now, as the branded color scheme surrounds you, you have to wonder: How? The Answer scrolls into view in the form of a giant blue rectangle on the floor below. Would-be riders can barely avoid stepping on it to get inside the trains: "MICROSOFT. Where do you want to go today?"

Booming from the floors, the walls, the staircases, the very rafters, is the message: Come work for Microsoft. Reading between the steps, as it were, it's hard not to also get the message: the software superpower in Redmond, Wash., is in desperate need of help to expand its 34,000-person company.

Mark Spain, a human resources director at Microsoft, says the immersive recruiting environment is just business as usual: "It's an extension of our existing campaign," which runs in airports and airline magazines. He wouldn't say how many new hires Microsoft is after, only that Microsoft is trying to drive "passive" job seekers to the jobs section of its Web site -- which lists primarily technical jobs.

In the San Francisco metro station, the steps between levels have been branded in Microsoft's chosen colors -- green, blue, yellow; every third step reminds you of the essential URL: "Microsoft.com/jobs." Microsoft. It's not just a career path. It's a carpet.

For tens of thousands of Bay Area commuters, the scene is surreal. Imagine waking one morning to discover that the Department of Justice had chucked its antitrust case, leaving one and only one company to make software, to work for, to exist. It's an incredibly unsettling feeling to be in a public space -- one which you may have no choice about passing through on your way to work -- in which every available surface is dominated by one company: Microsoft.

"Station domination," incredibly enough, is the term for the massive ad buy that has converted the Embarcadero station into Microsoft-land for the month of March. "It's the visual equivalent of surround-sound," says Brigg Hyland, a vice president of TDI Worldwide, a division of CBS that manages outdoor and transit ad space, including the Bay Area Rapid Transit stations. TDI does similar all-encompassing ad blankets in 18 subway stations around the country, but the Microsoft blowout is happening only in San Francisco.

Incredibly, an entire train station can be had for a mere $150,000 a month. (Maybe someone should mention that to those dot-com companies that spent well over $1 million for their forgettable 30-second Super Bowl ads.) For the $150,000 fee, Microsoft, or any other company, can take over not only the traditional advertising slots, but unusual spots as well, like the floor, the rafters and even the staircases.

"You basically have control of the station for a month," says Mike Healy, the public affairs director for BART. But he's never seen a company turn the space into a 3-D classified ad: "They must need the help," he mused.

Old Navy blanketed a San Francisco station to promote the opening of its flagship store in the fall; and right now Bridge Information Systems, a financial information services company, has wallpapered another station. Still, Microsoft's "station domination" comes with particularly ominous overtones, since its primary message is not "buy our product" but "become one of us and change the world."

"It's the little things that count, like making a difference. To a few billion people," reads one repeating sign.

"Your family still won't know what you do for a living. At least they'll know where," winks another, in an undisguised attempt to tarnish the start-up allure.

More than anything else the "station domination" campaign may be a testament to just how hard it is to get the attention of technical talent. Most tech companies are having a hard time filling their open slots, and are turning to advertising, professional recruiters and big finders fees to bring in new hires. Microsoft faces the same talent shortage -- plus it's vying for geek power with a slew of early start-ups still handing out VP titles.

"At Microsoft, we encourage you to direct your own career path. And on the weekends, to blaze your own trail," it promises -- as if to contrast with the start-up lore of pulling all-nighters and crashing in your cube. But seriously, does the most highly valued company on Earth expect us to believe it got where it is by taking weekends off?

But it's not the message or even the sheer ubiquity and dominance of the campaign that's odd, we'd expect ubiquity and domination from Microsoft, it's the odd target of the ads. After all, how many of those train passengers are software engineers, the primary jobs listed on Microsoft's site? Spain says that Microsoft wants to appeal not just to technical geniuses, but to anyone interested in one of "the different job sets potentially available in the company."

Still, BART reports that 33,750 people exit San Francisco's Embarcadero station on an average weekday; and those numbers don't reflect people traveling one way or transferring from other stations. But of those 33,750, how many, even in San Francisco, can be expected to respond to a solicitation that says "You'll be working on products that affect end-users in Bangladesh. Not bad for a first day." Are we all in the business of pleasing "end-users" now?

Microsoft's campaign suggests the technology industry has finally swallowed its own message, and the only viable way to "change the world" is to write code or product manage a Web site. "You could be working on something better," warns another ad. "Tick. Tock."

Shares