Some vaccines work too well. If the tetanus vaccine weren't so effective, the sight of people suffering from lockjaw would be commonplace. And when the bottom of the tetanus vaccine supply dropped out, as it did in January, we might have been worried. Instead, we hardly noticed.

America takes about 25 million doses of tetanus vaccine per year, and until recently, there were two main sources for it: Wyeth-Ayerst -- a vaccine manufacturing subdivision of pharmaceutical giant American Home Products -- and the French manufacturer Aventis-Pasteur. (A third company, Glaxo Smith Kline, makes the infant diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccine, DtaP, which is still widely available.)

But Wyeth-Ayerst dropped out of the market, leaving the medical community with a situation one doctor described as "a real problem" and another as "frightening." A vaccination required by law in 47 states is now in the hands of only one major company -- Aventis. And for the next 11 months, the amount of time it'll take Aventis to get up to speed, there's a good chance that if you ask your doctor for a booster shot, you'll be told to wait until next year.

American schoolchildren receive vaccines for tetanus, as well as measles, mumps, rubella, polio, meningitis and chicken pox. Getting your shots is a ritual as basic to American childhood as the Sunday comics. And most Americans, if they think about these medicines at all, probably assume that the government manufactures them or controls their supply. But the government got out of the business long ago, turning it over to more efficient private companies. The problem is that the vaccine business offers very low profit margins -- in large part because of well-meaning but hopelessly outdated price controls -- and if private manufacturers decide they're not making enough money and decide to get out, there's nothing to stop them.

The result is a looming public health crisis -- the first manifestation of which appeared last month, when the four companies producing a strain of flu vaccine all fell victim to manufacturing problems, causing widespread shortages. Like the flu vaccine shortage, the Wyeth-Ayerst affair is a case study of what can go wrong -- and will continue to go wrong -- in the vaccine industry.

Wyeth-Ayerst, which has already faced major embarrassment in the marketing of the diet drug fen-phen and other drugs, abandoned its tetanus vaccine production not long after the Food and Drug Administration slapped a major fine on it and asked it to improve conditions in its manufacturing plants. Wyeth, answering to its stockholders like any other private company, said good riddance -- and as a result, lockjaw may be poised for a comeback.

"Every 10 years we need boosters because immunity begins to wane," says Dr. Larry Pickering, a pediatrician with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's vaccine program. "The organism is still in the environment and if you don't get those boosters, [and if you] are exposed to it, like in a cut, without a proper inoculant, people will begin to develop it, and we will start to see more cases."

About 45 people develop tetanus each year, with older patients, who are less likely to be up to date on their booster shots, making up the bulk of the cases. On Jan. 5, an Associated Press story described the case of an 80-year-old woman named Fern Turner who developed tetanus from an infected spider bite. Turner spent 53 days in an intensive care unit with muscle spasms and a locked jaw, but she lived. The mortality rate for elderly tetanus suffers is over 50 percent.

Pickering can't say how many cases of tetanus we can expect to see as a result of the shortage; no one can, which makes it hard to find an impending public health disaster to rally around. Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a member of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee, comes a little closer, but not much: "We're pretty sure that we would have all these diseases if we didn't vaccinate, but we can't prove it. Science doesn't prove negatives."

Doctors can't say how much of a danger the tetanus vaccine shortage could be, but they can tell you that it points to a larger problem: The fewer sources we have for these crucial drugs, the more vulnerable the supply becomes and the more we put ourselves at risk for diseases most of us forgot existed.

Tetanus is one of those diseases whose onset is marked by symptoms so mild they're almost sinister: fatigue, soreness, irritability. A few days later, when the patient notices a stiffness around the jaw, and a labored breathing, it's often too late. As swallowing becomes difficult, the mouth fuses shut while the rest of the body is racked with muscle spasms so severe that a patient can break his or her bones.

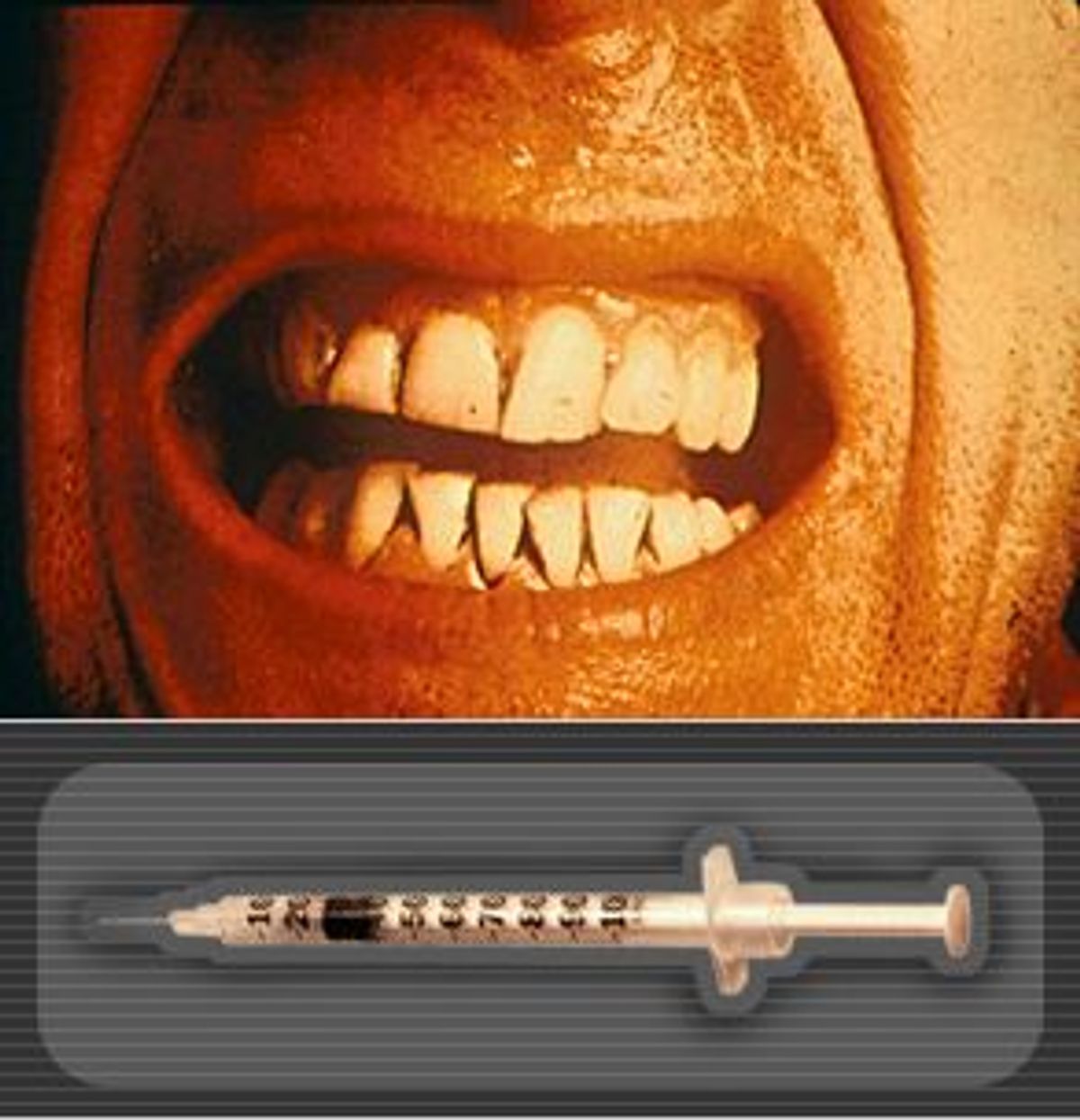

You don't quickly forget photos of tetanus patients, their faces frozen into something that would look like a smirk -- eyebrows raised, the corners of the mouth turned up into a smile -- if it didn't give off the distinct impression of a physical prison; tetanus patients look, literally, trapped in their own faces. Later, their bodies become fortresses too; tetanus stiffens the entire body into positions you wouldn't want to spend five minutes in. One photo shows a man bent backward into a crescent moon shape; another has a child's arms bent up at the elbows, like a boxer getting ready to punch, but immobile. The people in these photos look scared.

Dr. William Muraskin, author of "The Politics of International Health" and assistant chairman of graduate studies at Queens College, says, "If you have tetanus, you die." He's exaggerating, but not by a lot: In developed nations, about two-thirds of those infected with tetanus die, with those who catch the illness quickly more likely to survive. Recovery for tetanus can take months, during which time the patient is treated with a medical arsenal that's almost as scary as the disease itself: muscle relaxants, or medically induced temporary paralysis, weeks spent isolated in dark, silent rooms intended to reduce stimulation to the nervous system.

Tetanus is scary, but when you're a pharmaceutical company, it's the vaccine business that causes nightmares. In 1999, Wyeth-Ayerst caused a stir when it had to withdraw its rotavirus vaccine from the market, after an intense ad campaign and widespread usage. Rotavirus, a diarrhea-like sickness common among young children, is potentially deadly, but so, it turned out, was the vaccine, which caused bowel obstructions in dozens of children. The incident was particularly embarrassing to the FDA, which had approved the drug only a year before, officially recommended it to all children in the United States and then proceeded to vaccinate (according to a New York Times article on the withdrawal) 1 million 2-, 4- and 6-month-olds. Add to that the well-publicized recall of Wyeth-Ayerst's notorious diet drug, fen-phen (which was found to cause heart problems and cost the company $3.7 billion in damages), and you have a company justifiably wary of vaccine scandals.

The company doesn't cite earlier problems with its decision to drop the tetanus vaccine. Wyeth-Ayerst spokesman Doug Petkus won't say much beyond "We periodically evaluate our portfolio to see how we can better and more efficiently allocate our resources."

But Wyeth-Ayerst's announcement of its decision came just seven months after Justice Department officials entered the Wyeth-Ayerst warehouse in Venore, Tenn., on orders from the FDA to seize thousands of wrapped, ready-to-go syringes of tetanus/diphtheria vaccine and other drugs.

Such seizures are not uncommon, and in this case, the move came after a series of FDA warnings to Wyeth-Ayerst regarding the company's production of tetanus vaccines and other drugs. The paperwork around this event is a fax-machine hazard -- blurry, 25-page documents blotted with ink spots to cover classified information -- but it's possible to make out the FDA's charge. It wasn't Wyeth-Ayerst's vaccines that were found to be at fault, it was the packaging.

"Vials [found at Wyeth-Ayerst's manufacturing plant in Marietta, Pa.] had defects ranging from a slight 'nicking' to a complete 'chipping' around vial rim surfaces that present a potentially critical defect which cannot be unsuspected out following filling and capping."

FDA documents suggest that the company had been warned in the past about possible sanitation issues. However, Petkus, who spoke on behalf of the company at the time of the seizure, says that the FDA's complaints "referred in many cases to paperwork" and that beyond that, well, we'll have to ask the FDA. "Seizure is a process the FDA has at its disposal," he said, three times, "to indicate FDA is serious about its inspections." When asked about this seizure, and about the charges that vials containing the tetanus vaccine weren't meeting FDA standards, Petkus said, "That's not my recollection." Possibly, he suggested, the FDA seizures were a "symbolic gesture" of the agency's determination to be stringent with recently upgraded regulations.

Whether the FDA got what it came for is another question.

The FDA's seizure of tetanus vaccine from the Venore warehouse was reported in a handful of periodicals (some of which quoted Petkus as the company spokesman) and initial phone conversations with the FDA confirmed it -- which is why it came as something of a surprise when an FDA spokesperson (who declined to be named in this piece) called to say that, in fact, she'd been wrong about the seizure of tetanus vaccines from the warehouse; the FDA never seized any tetanus vaccine at all, she said.

"The FDA did not find [the tetanus vaccine] at the warehouse. They only seized products that were there and there was no tetanus toxoid in the warehouse. Intending to [seize the tetanus vaccine] -- if it was there -- and doing it are two different things."

Wyeth-Ayerst has a different account. "The seizure took place on June 15 and involved several injectable products," reads Petkus from Wyeth-Ayerst's report on the seizure. "The products involved were phenergan [a muscle relaxant], diphenhydramine and dimenhydrinate [both antihistamines] and tetanus/diphtheria vaccine"

In the FDA's telling, the vials of tetanus vaccines were presumably released into the marketplace; according to Wyeth-Ayerst, they never got that far. Both make a point of saying that the vaccines -- released or not -- were never a risk to public health. But the seizure, and the inspections that preceded it, were enough to convince the FDA that Wyeth-Ayerst would have to make some changes in its manufacturing process.

In October, the FDA and Wyeth-Ayerst hammered out a consent decree detailing Wyeth-Ayerst's agreement to bring its plant up to FDA standards and, importantly, levying a $30 million fine on the company. Three months later, Wyeth-Ayerst announced that it was getting out of the tetanus business altogether.

Wyeth-Ayerst won't explain why the company halted tetanus production, except to note, again, the process of portfolio review. But it's easy to come to at least one conclusion: Wyeth-Ayerst dropped out of the tetanus business, leaving a shortage, because making tetanus was bad business for it. The FDA demanded changes, and levied a fine, and presumably, that didn't bode well for Wyeth-Ayerst's profit margin. As a public company, it answered to the only people to whom it is obligated: stockholders.

According to Bob Snyder, a public health advisor for the CDC, there's a conflict of interest at the heart of the tetanus shortage, and the vaccine industry in general, that keeps vaccines in short supply. "They're a private company; they're not a philanthropy. Can we really force them to stay in business for products they don't feel confident about producing? Do we really want to use a product from a company we're forcing to make it?"

But why is the vaccine business so unprofitable?

For starters, old-fashioned vaccines like tetanus have traditionally sold cheap.

"Vaccines are expensive to make, expensive to do research and development on, and yet the return is very low, and the stringency of monitoring vaccine production is very expensive," says Stanford's Yvonne Maldonado, who sits on Wyeth-Ayerst's advisory board.

Vaccine manufacturing is one of the few industries in which having a monopoly on a product doesn't guarantee limitless price inflation. Sixty percent of the tetanus vaccine is bought by a single client: the CDC, which in turn supplies the vaccine to low-income and Native American children, Medicaid patients and the uninsured. The CDC needs the vaccine, but in a perfect example of well-meaning legislation gone all wrong, it is forbidden by law to pay market price.

Says Snyder, "When I put the bid out on the street for this product, nobody came. Nobody sent a bid in. They said, 'You've got to raise your price.' And my problem is, I've got legislation which says I can't raise the price."

The legislation at fault is the Vaccines for Children Program, which was established in 1994 to help the CDC distribute vaccines to families that otherwise couldn't afford them. The program met an important need, but it also stipulated that the price on those vaccines could only rise in accordance with the Consumer Price Index. When vaccine producers started raising prices (in response, in part, to tightening FDA regulations) the cost of the tetanus vaccine went up and the CDC found itself unable to afford it. That same year the agency exhausted its tetanus stockpile.

Changing the price cap would mean bringing the Vaccines for Children Program back to Congress, something the CDC is loathe to do. "Congress has to change the law," says Snyder, "and that's fraught with other problems. Once you open a law up, anything can happen. So we're in a quandary: Do we go back and risk having them appeal the whole program?"

From a dollars-and-cents point of view, vaccines are losers: People who take them don't get sick. People who suffer from heart trouble will continue to medicate five or six times a day, and a diabetes patient, says Maldonado, "will be on drugs for the rest of his life." But most of us will only come back for tetanus vaccines a couple of times before we die. The vaccine seems to be working, so -- to the dismay of the vaccine producers, and to our own minor health risk -- we forget about it.

Another disincentive for vaccine manufacturers is the anti-vaccine lobby. Thanks, in part, to a powerful campaign linking childhood tetanus vaccinations and autism, vaccine opponents have succeeded in raising the price of those vaccines to consumers, via the Vaccine Compensation Program.

Established in 1988, the program imposes, for every dose of vaccine bought, a preemptive payment for potential damages caused by that vaccine. Pay $7.50 for a dose of tetanus vaccine, and you're putting $1.50 into the Vaccine Compensation Program Fund, which doles out money to those claiming adverse reaction to the vaccines (required by law for children). The goal is to give the producers a little breathing room and to encourage the production of vaccines with a diminished threat of lawsuits. But, in effect, what the program does is raise the prices of vaccines, forcing manufacturers to charge more for them. Again, what's intended to help is only exacerbating the problem.

Those who are trying to provide tetanus vaccine are, in Snyder's words, caught "between the devil and the deep blue sea."

The CDC can't force a company to stay in the vaccine market, but in the event of a public health crisis (which tetanus is unlikely to pose), they could step in and offer to subsidize production of an unprofitable product. Indeed, those kind of subsidies may be in the works -- an arrangement the CDC's Larry Pickering hints at when he says "We have to work together to ensure a safe, effective vaccine supply." Still, that kind of cooperation between a private company and a government agency raises prickly issues: How much profit, for instance, should the CDC guarantee private companies from the sale of legally mandated vaccines?

The sentiment among many doctors and public health officials is that until we face a major outbreak of something preventable, like tetanus or measles, we aren't going to see any meaningful changes in how the drugs get made and sold. "The bottom line is this is gonna have to fail," says Dr. Maldonado. "There'll have to be some cracks in the dike before we can fix this." It may be that before we can secure the supply of vaccines against the diseases that threaten us, we'll have to start getting sick first.

Shares