It sounds like a no-brainer for struggling bands:

Just sign a contract giving an online music distributor like MP3.com free, unlimited distribution rights to your original music, and bingo! Not only are you on the road to stardom (“Sell CDs!” trumpets MP3.com’s online artist sign-up sheet. “Get famous!”) but you get to thumb your nose at the traditional recording industry along the way.

For Dana Woodaman and thousands of independent musicians like him, however, the reality doesn’t even come close to the hype.

“I’ve sold a total of one CD online, and I think that’s pretty typical,” says Woodaman, who first began uploading tracks from his self-produced Brain Transfer Project to four online music distribution sites nearly a year ago.

If industry figures are any indication, Woodaman’s guess is on the money. In August, MP3.com sold 15,600 CDs on behalf of 26,700 artists listed in its online database, according to the digital music news service Webnoize. That’s about half a CD per artist. And MP3.com is not alone.

“Half a CD per month is pretty standard among the top three [online music distributors] in the indie space (IUMA/Internet Underground Music Archive, MP3.com, and Riffage.com),” admits Antony Bryden, general manager of IUMA, which was acquired by the digital download site EMusic.com earlier this year. “Per band, that works out to about $3 a month.”

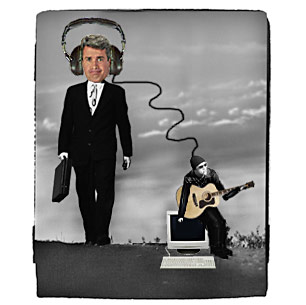

Online music distributors have been enormously successful at painting a picture of themselves as a virtual David out to slay the mighty recording industry Goliath. By promoting themselves as cool anti-establishment sites fighting the good fight on behalf of downtrodden musicians everywhere, online music distributors have persuaded thousands of musicians to hand over their tunes, no questions asked. As a one-time Web developer and the wife of a jazz guitarist, I’ve been amazed at the difference between how Net-savvy entrepreneurs and musicians have reacted to the online music industry.

By all accounts, indie artists are signing over their material in record numbers — putting up their songs free of charge on sites like MP3.com or Riffage.com in hopes of selling CDs, or signing over their work to online record labels like EMusic, which sells downloadable music for over 150 established labels plus independents. Of course, many of these artists are “weekend warriors,” whose music might have been heard by few people other than their hometown buddies before getting some exposure through an online distributor. And the fact that they’re not making money through online distributors might have as much to do with the quality of their product as with distribution.

Be that as it may, if MP3.com isn’t making money yet there are those who think it will someday. The company went public in July with a valuation exceeding $1 billion.

The reason? In a word, marketing. The distributors have done a great job of convincing the musicians that MP3 can reinvent the power structure.

After all, it’s a digital revolution! If you listen to the online music distributors, the big record companies are running scared: The Internet puts the reins of power back into the hands of the artists! What online music distributors really mean, of course, is that the Internet puts the reins into their hands.

Despite attempts to cultivate an image as a grassroots community dedicated to helping struggling independents, the average online music distributor’s business model is enough to make any red-blooded record executive blush.

Revenue streams in from music fans buying CDs and digital downloads, from advertising and from the artists themselves, who split revenues from CD sales and sometimes pay for placement on the sites. And all of this revenue is based on inventory the online music distributors obtain free.

“No one’s paying independent artists right now,” says Brandon Barber, product manager of digital music for Tunes.com, which was just acquired by EMusic. Tunes.com, a music hub that runs RollingStone.com, TheSource.com and DownBeatJazz.com, offers professional music reviews and Webcasts of concerts in addition to downloadable music. According to Barber, Tunes.com is considering paying artists in the future for downloadable music and taped performances, but is “trying to be as agnostic as possible until a standard emerges.”

The creators of the music could point to copyright law, which is supposed to ensure that artists get paid when companies make money off their music. Why aren’t online music distributors coughing up performance and mechanical licensing fees like everybody else?

Simple: They don’t have to. Not to independent artists, anyway, who — unlike their label-backed counterparts — often lack both business savvy and bargaining clout. Eager for exposure at any cost, many indie artists sign contracts giving away those rights.

Most online music distributors realize this is a contentious point and say they are trying to negotiate the issues of artist profits and copyrights. Jim Werking, president and CEO of AustinMP3.com, says his company is among those that do not currently compensate artists. But his start-up that distributes downloadable MP3s by artists in Austin, Texas “plans to create opportunities for artists to profit from their work.” As Werking puts it, “Nobody knows what’s going to happen with online music.”

“It’s absolutely ridiculous,” says Vicky Moerbe, a veteran of the music business and current manager of Austin favorites W.C. Clark and Seth Walker. “The Webcast contracts I’ve seen expect musicians to sign away everything. Not just the right to broadcast their shows, but to archive them, turn them into CDs, make money off them from now until forever — all without paying the musicians a dime. You know, musicians make little enough as it is, and here these companies are trying to get rich off them.”

The American Federation of Musicians, the largest professional musicians’ union in North America, agrees.

“The bottom line is that these companies want to distribute recordings without even attempting to compensate the artists,” says Ginger Shults, vice president of the Austin chapter of the federation. “We’re very concerned.”

To be fair, not all online music distributors require artists to give away all rights in all circumstances. MP3.com, for example, doesn’t compensate musicians for individual tunes that are downloaded or sold as part of a sampler (multiple artist compilation) CD, but does share revenues from selling artists’ full-length CDs off the site. According to MP3.com’s site, the 50 percent paid to artists in these cases is far above the “10 percent most traditional record labels offer.”

Comparing an online music distributor to a traditional record label, however, is misleading. In exchange for the high percentage they make off CD sales, record companies fork out big bucks. They pay for a CD to be recorded, mixed, mastered and pressed and they pay to develop the artwork and promote the finished recording through established radio and print channels. By contrast, sites like MP3.com offer none of these services; they simply offer to sell a finished product.

Without exception, online music distributors assert that they are, in fact, giving musicians something of value in exchange for the music they receive: Exposure.

Sounds good on the surface — as long as somewhere, at some point, exposure turns into dollars (or landlords and grocery stores suddenly start accepting “exposure checks”). And there’s no reason why it shouldn’t: Exposure has been recognized as a quantifiable, profitable marketing concept for years, and the Web is a marketer’s dream come true. Webmasters can track who visits a Web site, how long they stay, who’s downloading which MP3 files — virtually every demographic in the book. Web software gives artists the unprecedented ability to track and quantify their exposure so they can turn it into a tangible asset, like CD sales or bodies at their next gig.

What artist wouldn’t want to know that 90 percent of her fans are concentrated in Altoona, for example? What artist wouldn’t want to be able to send a message to all of the fans who’ve downloaded his MP3s, to let them know where he’s playing and that he’s got a new project in the works? Imagine being able to show up at a label exec’s office waving proof that 500,000 people loved your last self-produced single.

Unfortunately, for all their breast-beating about leveling the playing field for independent musicians, some online distributors argue that details about how the public responds to an artist’s work is too valuable a commodity to share. “Tunes.com provides that information [comprehensive download details] for the labels we work with, but not for the individual artists,” says Barber.

The only information that is routinely passed on to independent artists is the number of times their song files have been downloaded. Artists who aren’t given special, front-door promotion on a digital music site typically generate a few hundred downloads or less a month; featured artists can generate ten times as many. And increasingly, decisions about who gets into the spotlight are based on cold, hard cash.

MP3.com, for instance, recently instituted a promotional campaign called “Payola,” which urges artists to bid against one another for the right to purchase extra exposure on the MP3.com site. The cost of the extra exposure fluctuates based on the number of artists competing; recently, $80 snagged top billing of an alternative band’s song for one week.

Of course, with the free tools and access available from just about any $20-a-month Internet service provider, a musician can whip up a Web site with performance schedules, e-mail, and gig announcement lists. She can encode her own tunes in whatever audio format she chooses — like RealAudio, so that fans can listen to the music but not own a copy, or a downloadable format like MP3. And she can easily sell her own CDs. (Third-party companies like CCNow will take care of credit card processing of individual CD orders for 9 percent off the top.)

The thing that online music distributors have promised to add to this mix is eyeballs. MP3.com reports more than 10 million pageviews per month. But lots of traffic to a music distribution site doesn’t necessarily add up to lots of exposure for any one artist.

“MP3.com used to be a great way to get attention,” says independent musician and MP3.com contributor Karl Rehn. “But now that the record companies have started putting money into MP3.com and the number of artists online has jumped exponentially, it’s back to the way it’s always been.”

For all the hype, the Web does offer musicians one potentially revolutionary advantage over every other medium in existence: The ability to reach fans and distribute music worldwide, independent of any aggregator — online or offline, traditional or nouveau.

But, as with any revolution, the spoils will fall not necessarily to the neediest, but to those who recognize opportunity and seize it. While there’s no question that the online music battle is far from over, whether the victor will turn out to be big business or independent artists remains to be seen.