Microsoft supporters are calling the federal appeals court ruling on the Microsoft antitrust case a victory for Microsoft. Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson's order to break up Microsoft has been nullified, the case is being sent back to the District Court, and the judge has been disqualified from further participation, based on his own "flagrant" violations of the Code of Conduct for federal judges.

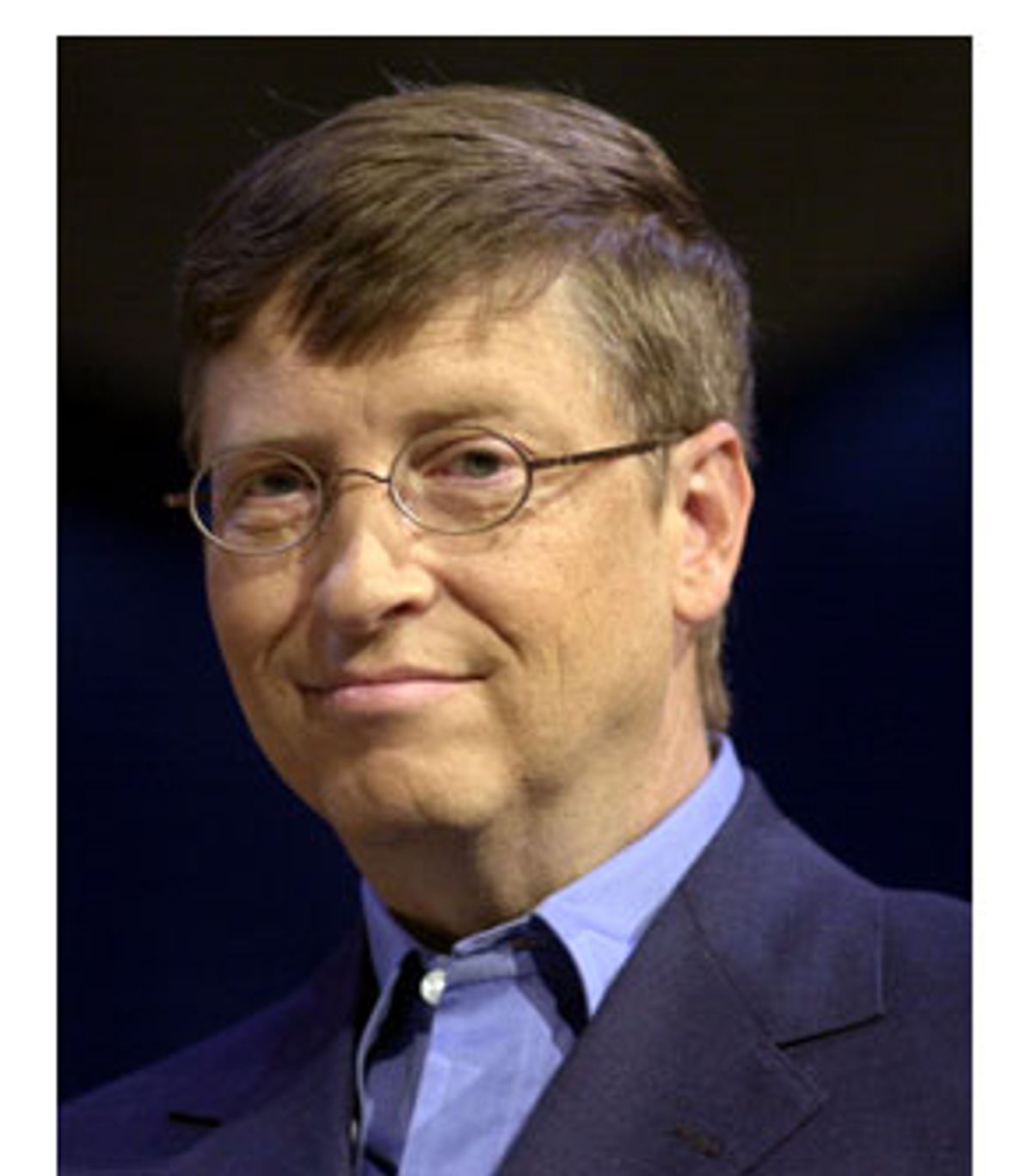

As Bill Gates himself said in a press conference on Thursday, "We're very pleased ... We feel very good about what the court has written here."

But the 125-page opinion from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit also holds that Microsoft is a monopoly and has behaved anticompetitively -- that, in fact, it violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. For the most part, the court upheld Jackson's findings of fact, which recounted in voluminous detail how Microsoft abused its control of the market for operating systems to gain market share for its Internet Explorer Web browser, at the expense of Netscape Navigator. To some legal observers, the court's findings of liability on various monopoly power abuse issues constitute a huge defeat for Microsoft, one that may require the software company to appeal immediately to the Supreme Court.

Specifically, the appellate court agreed with the Department of Justice prosecutors and Judge Jackson that Microsoft had abused its monopoly power by forcing computer hardware makers (OEMs) into signing licenses that restricted their rights to preinstall Netscape Navigator, by integrating I.E. into the Windows operating system in such a way as to make it more difficult for Netscape to compete ("commingling" browser code and operating system code, and failing to provide an option to remove Internet Explorer), and by engaging in deals with Internet service providers and other Internet content companies that gave preference to Internet Explorer.

In sum, the analysis of the court could be devastating to Microsoft. "The core of the case is that Microsoft has lost," says Lawrence Lessig, a professor at Stanford Law School. "They violated the antitrust laws, and the real issue is now remedy."

And yet, at the same time, Microsoft has much reason to rejoice. Not only did the court modify a few of the findings of legal liability -- for example, it ruled that the District Court had not made the case that Microsoft engaged in illegal "tying" by bundling its browser with the operating system, and asked the court to apply a different legal analysis if it wished to revisit that argument -- but it also was able to take advantage of astonishing errors on the part of Jackson that essentially required that his order to break up the company be nullified.

The court ruled that Jackson's failure to allow a hearing in which Microsoft could have protested the breakup remedy was impermissible, but it saved special scorn for Jackson's behavior in making public comments about the case to reporters while the case was still ongoing: "The violations were deliberate, repeated, egregious, and flagrant." It did not find evidence that Jackson was biased in his findings of fact, but it did hold that there was reason to believe that his venting of animus against Microsoft during the very period in which he was crafting his remedy could have affected the shape of that remedy.

So what does it all mean? Perhaps the only thing that is really clear is that the nation's most important antitrust case in a generation is far from over. Both sides have reasons to appeal to the Supreme Court -- the Department of Justice can try to protest the nullification of the remedy hearing on the basis of Jackson's behavior, and Microsoft can try to fight the upholding of the findings of fact. But a further wild card is the change in presidential administrations. Will the Bush Department of Justice seek vigorously for a new punitive remedy, will it come to some kind of settlement with Microsoft, or will it simply drop the case?

Few longtime followers of the case are willing to handicap the Justice Department's likely strategy. But there are some factors that might dissuade a Bush DOJ from folding its tent and letting Microsoft walk away. For one thing, there is the issue of the various antitrust actions being brought against Microsoft by individual states. As Eliot Spitzer, New York's attorney general, said in a statement, "the court unanimously affirmed the core claim of our case that Microsoft has willfully and repeatedly violated antitrust laws, whose prime mission is to protect consumers and business from the behavior of a monopolist." Regardless of Attorney General John Ashcroft's feelings about antitrust enforcement, many legal experts feel the states are unlikely to retract their claims against Microsoft, given the decisions of the appellate court.

Certainly, if the Justice Department does intend to continue its prosecution, it has every reason to do so.

"We uphold the District Court's finding of monopoly power in its entirety," asserted the appellate court.

"Microsoft reduced rival browser's usage share not by improving its own product but, rather, by preventing OEMs from taking actions that could increase rivals' share of usage ... Microsoft's conduct, through something other than competition on the merits, has the effect of significantly reducing usage of rivals' products and hence protecting its own operating system monopoly; it is anticompetitive."

Anticompetitive behavior? On first glance, longtime Microsoft foes might finally be able to say that they have won. But they can only be gnashing their teeth as they consider how Jackson's indiscretions gave the appellate court plenty of room to prevent any immediate progress toward a Microsoft breakup. Meanwhile, Microsoft can continue doing as it pleases, unhampered by any current legal restrictions or punishment for past behavior.

Shares