Lloyd Kowalski violated Microsoft's copyright without much hesitation. The veteran Philadelphia computer teacher (who asked that his name be changed) never expected to be punished. He didn't even think what he'd done was wrong. When he installed his school's only copy of Microsoft Office on several teachers' computers last January, he figured he was doing a good deed -- helping frustrated teachers, making their school days just a little bit less overwhelming.

"It was a minor violation," he says. "We use AppleWorks for word processing but I put Office on their computers because they couldn't read the Microsoft Word attachments they kept getting from the district's central office. It was easy to do, and it made sense since our schools are in dire financial straits."

But this spring, Kowalski discovered that Microsoft didn't care much for his reasoning. Following an anonymous tip, the software giant launched an investigation of Philadelphia's entire public school system. Microsoft threatened to sue unless the administrative offices and all 264 schools conducted an audit and proved that every piece of installed Microsoft software had a valid license.

The district is still completing the process, but on May 16 -- just before final exams -- teachers and administrators received a letter from the central office commanding them to complete an inventory of every computer, every piece of installed software and every Microsoft license or proof of purchase. The memo also emphasized the serious stakes: "In an effort to avoid potential liability to the District in a time when finances are tight, we need all schools and offices to complete ... the computer and software inventory," it said. "Failure to meet the deadlines will result in your school or office being out of compliance, which will cost the school or office a substantial amount of money."

The district's chief information officer, Ron Daniels, says Microsoft has been "very supportive" during the audit, helping to trace licenses in its database. For its part, Microsoft representatives say that the audit is simply standard procedure. Working alone or through the Business Software Alliance (BSA), an industry wide enforcement group, Microsoft has been fighting the spread of illegally copied software for over a decade. Its most common targets are companies that copy software and then resell it illegally, but it's not unusual for urban, low-income schools to end up caught in the net too. But such schools aren't being singled out, say Microsoft and BSA attorneys. Once discovered -- typically through tips that come via hotlines like 1-800-RU-LEGIT -- they're treated just like any other violator, says Jenny Blank, BSA's director of enforcement.

"The copyright law should be applied universally," she says. "What is it we're trying to teach these children anyway? Are we teaching them that its OK to steal? The message we need to get to them is that intellectual property deserves to be respected."

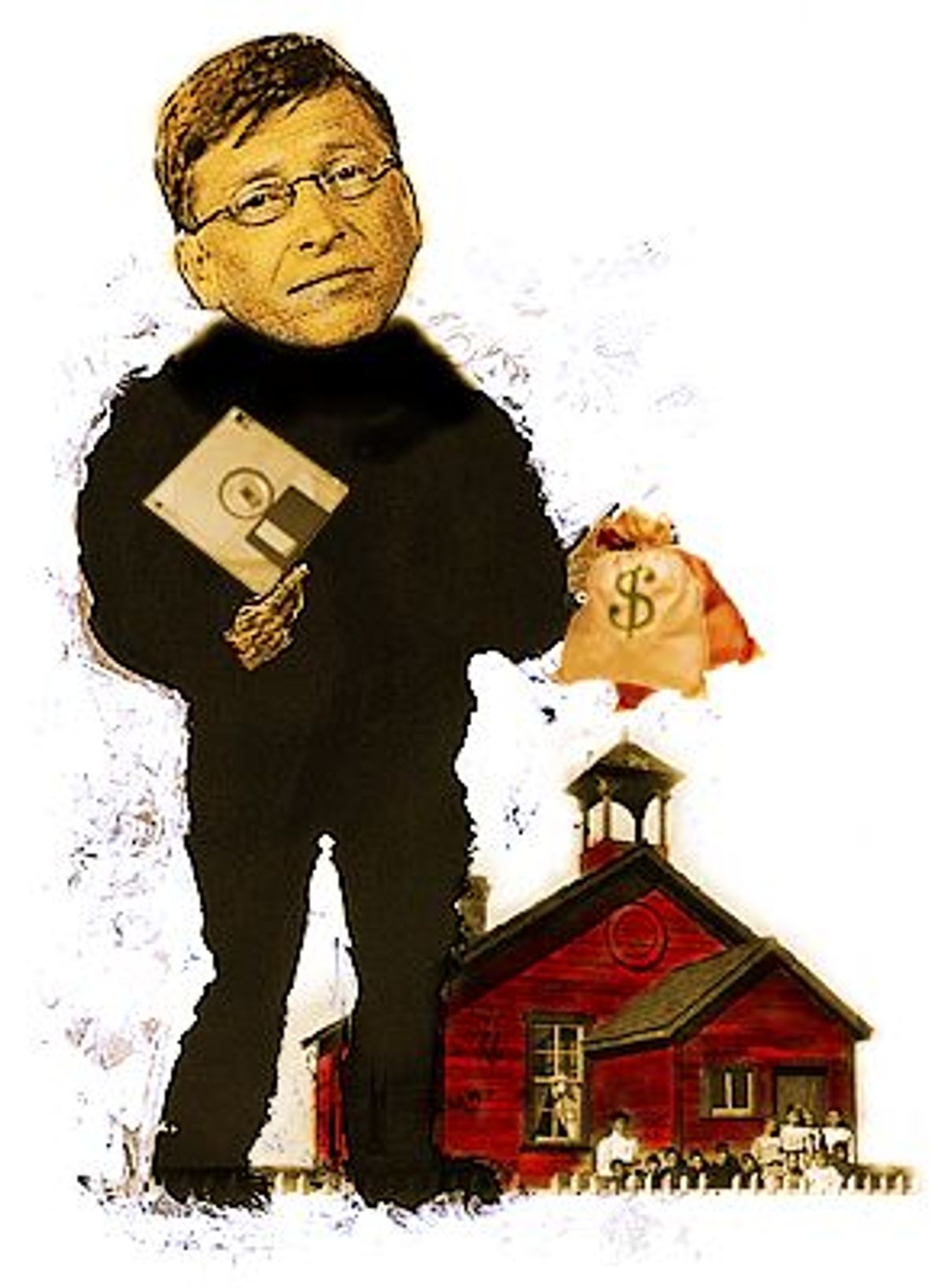

But critics in Philadelphia and elsewhere say that Microsoft and the BSA have their priorities out of whack. They argue that educators shouldn't have to pay exorbitant prices for software in the first place, but more importantly, that no public school should be compelled to play by the rules of an ever-changing license system that treats cash-strapped educational institutions just as it does for-profit businesses. Philadelphia in particular, they argue, deserves an even greater degree of understanding. Its schools and students are some of the poorest in the country. At the end of June, city officials announced that without a massive influx of state or federal cash, the district won't be able to pay its 27,000 employees through the upcoming school year.

"It's kind of like AIDS in Africa and the drug companies," Kowalski says. "Can anyone expect a dying person to be concerned about the drug companies' profits?"

The conflict between educational priorities and intellectual property protection is, on one level, a moral question -- what do we as a society think is more important? But there's also a practical aspect to the struggle that may ultimately make the moral question moot. By ratcheting up pressure on schools and imposing financial penalties, Microsoft is inviting educators to search for other, cheaper alternatives. And in today's software industry, there actually may be another choice, or at the very least, the potential for another choice.

Impelled in part by fiscal realities and in part by intellectual curiosity, educators are beginning to take a hard look at free and open-source software programs -- products that are created by volunteers and can be distributed without restriction. Adequate replacements for Microsoft Word or Outlook may not yet be ready for prime time -- but the harder Microsoft pushes, the more incentive educators have to join the world of free software, and turn potential into reality. The Philadelphia public school system may not be able to deflect Microsoft's legal assault, but in the long run, Microsoft and other proprietary software companies may be the ones that end up wounded.

One of the first and most-discussed scuffles between the software industry and schools started back in 1996. The Business Software Alliance, which includes Adobe, Intel, IBM and Macromedia as members, received a tip about a Los Angeles school that was supposedly using more than 1,000 copies of unlicensed software programs. The BSA asked the district to investigate, and after auditing the school in 1998, the school district, working with the BSA, discovered several hundred unauthorized copies, including 132 versions of MS-DOS, according to a Los Angeles Times report.

The total cost of the copying could have run into the tens of millions. Each violation carries a potential penalty of $150,000; the fines for just the MS-DOS copies could add up to as much as $19.8 million, not even counting lawyers' fees. The district had already spent loads of cash on technology -- $8 million during the 1995-96 school year alone.

"We're a large school district, but compared to Microsoft, we felt like we're the little guy being beaten up," says David Tokofsky, a member of the Los Angeles school board who has worked in L.A. schools for more than a decade. "The BSA is a CIA-type organization that infiltrated a cash-strapped large entity that's dependent on public funds. Then they told teachers -- who can't get enough services to kids already -- that they were committing crimes. It's like Xerox walking into a major university and arresting students for copying essays."

The school board, however, chose to settle rather than fight. It eventually negotiated a reduced settlement: a $300,000 fine, in addition to which the cash-strapped district had to set aside $3 million to replace pirated materials, and another $1.5 million to create an internal piracy team. The BSA claimed that the punishment could have been much tougher, but its attempt to portray itself as lenient fell on deaf ears. The industry's image as educationally friendly had been tarnished.

"In the court of public opinion, the BSA lost," Tokofsky says.

Microsoft and the rest of the software industry responded to the public relations setback with a two-pronged approach. Individual software companies defended their actions as economically and morally justified, but they also strove to improve community relations. Microsoft had been equipping libraries with Windows computers since the beginning of 1998 -- an initiative that some condemned as self-serving -- and two years later, the Gates Foundation set aside $350 million for schools, particularly small, rural districts. (Technology giveaways are not part of the program, says a Gates Foundation spokesperson, but grant winners often use the money to buy Microsoft products.)

Microsoft and the BSA also expanded their public service campaigns, alerting schools to educational discounts and software management tools aimed at helping administrators keep tabs on their computers. Microsoft even went one step further. While the BSA pours its collections -- $60 million over the past 9 years -- back into enforcement, Microsoft pledged in 1999 to return $25 million (over a five-year period) to needy nonprofits and schools in the areas where it had collected anti-piracy fines.

"It's part of Microsoft's overall approach toward philanthropy," says Devin Driggs, a Microsoft spokesperson. "It's designed to promote innovation and entrepreneurship in the area of science and technology."

But does the benefit of school giveaways outweigh the costs paid by schools that are the subject of anti-piracy inquires? Relevant statistics on the affected schools are in short supply. The Department of Education doesn't track piracy cases in schools and neither Microsoft nor the BSA would release information on the number or location of schools that have been investigated.

But this much is clear: Los Angeles and Philadelphia are not the only urban, low-income school systems to attract the unwanted attention of Microsoft and the BSA. British teachers in Birmingham -- a heavily working class city in central England -- reportedly received letters last year from Microsoft telling them they were sitting on a "legal timebomb" that they'd better clean up. The San Jose (Calif.) Metropolitan Education District (MED), which teaches vocational classes to about 70,000 adults and high-school students, also tangled with the BSA. And according to Mike Beever, assistant superintendent for business services, the process itself serves as a form of punishment.

"Someone phoned in a tip last year and when the BSA came to us, they demanded a complete audit within 30 days," says San Jose's assistant superintendent Beever. "I don't know how anyone could comply that quickly."

Beever figured that Microsoft would be able to help. "I called them to see if they had some software that could help us do the inventory, but they didn't have anything," Beever says. "They didn't even have a complete record of the software we purchased."

So the MED, with its small technical staff and 800 networked and stand-alone computers, hired outside help. In the end, the audit discovered about 50 to 100 cases of illegally copied software, says Beever. The BSA contended that it was entitled to $560,000 in fines and software payments, Beever says, but then suggested a $100,000 settlement. Beever, frustrated with what he calls "heavy-handed tactics," refused. In March, the parties agreed to a $50,000 fine. But with the extra staffing and other costs, Beever estimates that the ordeal cost San Jose about $200,000.

"They're not serving the educational community by taking such a hostile approach," he says. "They should be working with districts to help them manage their software but all they're interested in is enforcement and collecting fines."

Both Microsoft and the BSA argue that they're interested in compliance, not enforcement. "Our goal and intention is not to have this enter the courts," says Nancy Anderson, Microsoft associate counsel. "We're not trying to bring cases against our customers." And contrary to critics' claims, she adds, Microsoft treats educational institutions quite differently from businesses. Through the technology School Agreement program, districts can purchase subscriptions to Microsoft software suites, which offer a 50 to 90 percent discount, according to Microsoft figures.

Philadelphia may not have had the time or money to switch over, but since the enforcement process started, says the Philadelphia school district's chief information officer Ron Daniels, Microsoft has acted more like a partner than police officer. "We worked with Microsoft to develop a piracy plan which included education, proactive detection measures and ultimately an audit," he says. "All and all, Microsoft has been very supportive and has provided us with tools such as an online database to verify our licenses and has even donated over $20,000 to assist our schools."

Still, Philadelphia teachers and parents -- along with outside educators -- argue that Microsoft hasn't gone far enough. Intellectual property law should take a backseat to education, says Kowalski, who, incidentally, asked that his real name not be used because he was afraid of retaliation from both Microsoft and his own school district.

"Yes, software is copyrighted, but my concern is educating students in an urban school who are already deprived of so much," Kowalski says. "The district expected teachers to do this [the audit] at the end of the school year when final grades are being compiled -- which says something about priorities."

"The Philadelphia school district has no money," adds Barbara Hearn, a parent of two children in the public schools. "The state already took over the parking authority to pay for the schools, and there's still not enough money."

The problem is that Microsoft and other software companies view schools as simply another lucrative field for sales, says Robert McClintock, director of the Institute for Learning Technologies, a tech-focused research group at the Teachers College of Columbia University.

"These companies should become far more proactive in solving educational problems and helping schools, rather than maximizing the market," he says. For years, software companies have failed to recognize that schools could be development partners. "And as a result, a lot of educational programs, per se, are kind of undercapitalized," McClintock says. "Many of the big companies are selling office software for educational use and the licensing patterns are not well designed to meet the needs of educators and students."

Jamie McKenzie, publisher of a popular educational technology journal, says the industry's enforcement tactics "are not heavy-handed at all" -- but even he argues that the industry could be doing a much better job with education.

"It's become a self-serving and cynical industry," says McKenzie, a former superintendent of the Valley Forge, Pa., school district. "While I have no sympathy for anyone stealing software -- we do need to teach our kids about intellectual property -- companies should allow for a lot more fair use. American corporations have made far too much off of schools. [Software companies'] ability to be philanthropic is pretty wide open, but most of them are just promoting the 'digital divide' as a way to drive sales."

No matter how hard-line the software industry gets against the schools, there's one option that simply can't be considered: opting out entirely. Computers are now considered crucial curriculum elements, frequently as early as kindergarten. Internet access is a must-have, and for many parents, computer skills are high on the required learning list. But serious anti-piracy tactics, which Microsoft claims to have ratcheted up in recent years, do have a downside for the software industry: They threaten to inspire a widescale shift away from proprietary software and toward cheaper, if not free, options.

San Jose's Mike Beever, for example, started considering open-source alternatives after his brush with the BSA. Open-source software is software for which the underlying source code is made freely available to the general public. There are no restrictions on copying, modification or even resale. Over the last five years, free and open-source software has proliferated on the Web and teachers all over the world are paying attention.

Especially in the arena of productivity applications, today's current state-of-the-art free software programs are not yet a slam-dunk alternative to commercially available offerings. But the gap is narrowing, says Columbia's McClintock. Teachers can now find free software that will help students draw geometrically correct formulas or molecular structures, or programs capable of mapping local crime patterns and pulling out trends. They can also create free virtual classrooms, or augment traditional classes with network applications like the University of Texas' LinguaMOO.

One ambitious group of educators has even launched a Web site called OpenSourceSchools.org that aims to act as a school technology warehouse -- a place with "all the basic pieces, and the help necessary, for an open source tech program." A Web server, network tools, mail, bulletin boards, course building systems, library system and school database system will all be offered as of October, says co-founder David Bucknell.

Bucknell and the other founders are hoping that the site will instruct teachers in the value of open-source, while also giving them a place to ask questions and try out what's available. Eventually, they figure, educators will recognize that open-source software and education belong together.

"A project [like the open-source software movement] that is people-oriented, open to scrutiny and altruistic by design -- successive generations are guaranteed the rights of their forebears -- is right for education," says Bucknell. "Education is the place open source began, as a means of ensuring the possibility of computer science itself, and education is the place where it has the best chance of becoming 'the way' things are done."

Already, some schools are forging into the free software world. Dozens of school systems now use Sun's StarOffice, a free, open-source competitor to Microsoft Office which has also been adopted recently by the U.S. Department of Defense. Teachers, administrators and students at two New York public schools -- Bronx Science and the Beacon School -- have gone even further, switching over some systems to Linux-based operating systems and writing their own free software.

At Bronx Science, Ted Nellen has created what he calls CyberEnglish, a computer-aided reading and writing course. Instead of simply researching Shakespeare in the library, Nellen's students have Net-enabled computers on their desks in class. They communicate about each other's work via e-mail, Nellen posts the class's schedule on a Web page and each student mixes listening to Nellen's lectures with individual instruction. Almost every piece of software that's used was obtained at no cost.

"I don't think I've bought a piece of software in years, since I now use free stuff and what comes bundled," Nellen says. "Proprietary software isn't an issue. Open source is changing this a great deal and the Internet has helped. I think as more and more kids get online and begin seeing how easy it is to work with open source, they will."

The Beacon School's students get an open-source education from the start. Mandatory freshman computer classes include lessons on Linux-based systems and Pine, a free e-mail program from the University of Washington. The Beacon's teachers have also written three free software programs of their own. One helps teachers publish homework assignments on the Web so parents can keep track; another helps students publish their own online newspaper; and a third gives teachers and student advisors instant, secure access to students' personal files. Whenever a teacher enters a comment about, for example, a student's slipping grades in Math, his or her advisor immediately receives an e-mailed alert.

More than 100 schools have contacted Beacon's technology department to find out more about the software, which is available free of charge, says Chris Lehmann, the Beacon's technology coordinator. Once he and other teachers and programmers finish this summer's project -- portal software that could guide, for instance, calculus students to a calculus home page -- Lehmann predicts that even more schools will inquire.

Along with saving the school thousands of dollars, "open source technology makes the most sense for education," says Lehmann. "Good teaching wants open pedagogy; good teaching wants students to understand why things happen. Open source allows that. It rewards curiosity, it gives students the chance to see exactly how things work, which is exactly what we're aiming for in education."

Five years from now, Nellen and Lehmann's stance will probably be considered commonplace, says McClintock. Linux-based systems and other free software applications could command the majority market share in schools within the decade.

"Open source isn't quite there yet," he says. "There needs to be a good presentation in an operating system, as there is in StarOffice, and there needs to be a good package of Internet capabilities. But when it all comes together, schools will start having a zero dollars software budget, which is what I've been advising for a while."

Philadelphia would clearly welcome the opportunity to access software without paying. The school district is running an estimated $200 million deficit for the coming year. But for now, it must deal with Microsoft's demands. Kowalski considers the scenario a veritable tragedy; Microsoft is saying that schools must comply with the law, regardless of circumstances. But Tokofsky, speaking from Los Angeles, believes that the relationship between schools and the software industry must change. Instead of absorbing "the missile of Microsoft's anti-piracy campaign," he says, teachers, parents, and school boards should start fighting back.

"They should send a multiple warhead back at Microsoft and say we're willing to go to court, we're willing to fight for our students," he says. "Because in the court of public opinion, Microsoft will lose. As a former teacher myself, I know there was no [malicious] intent in the copying that they're doing. The only intent they have is to get more poor kids connected to the computer, and that should matter more than intellectual property."

Shares