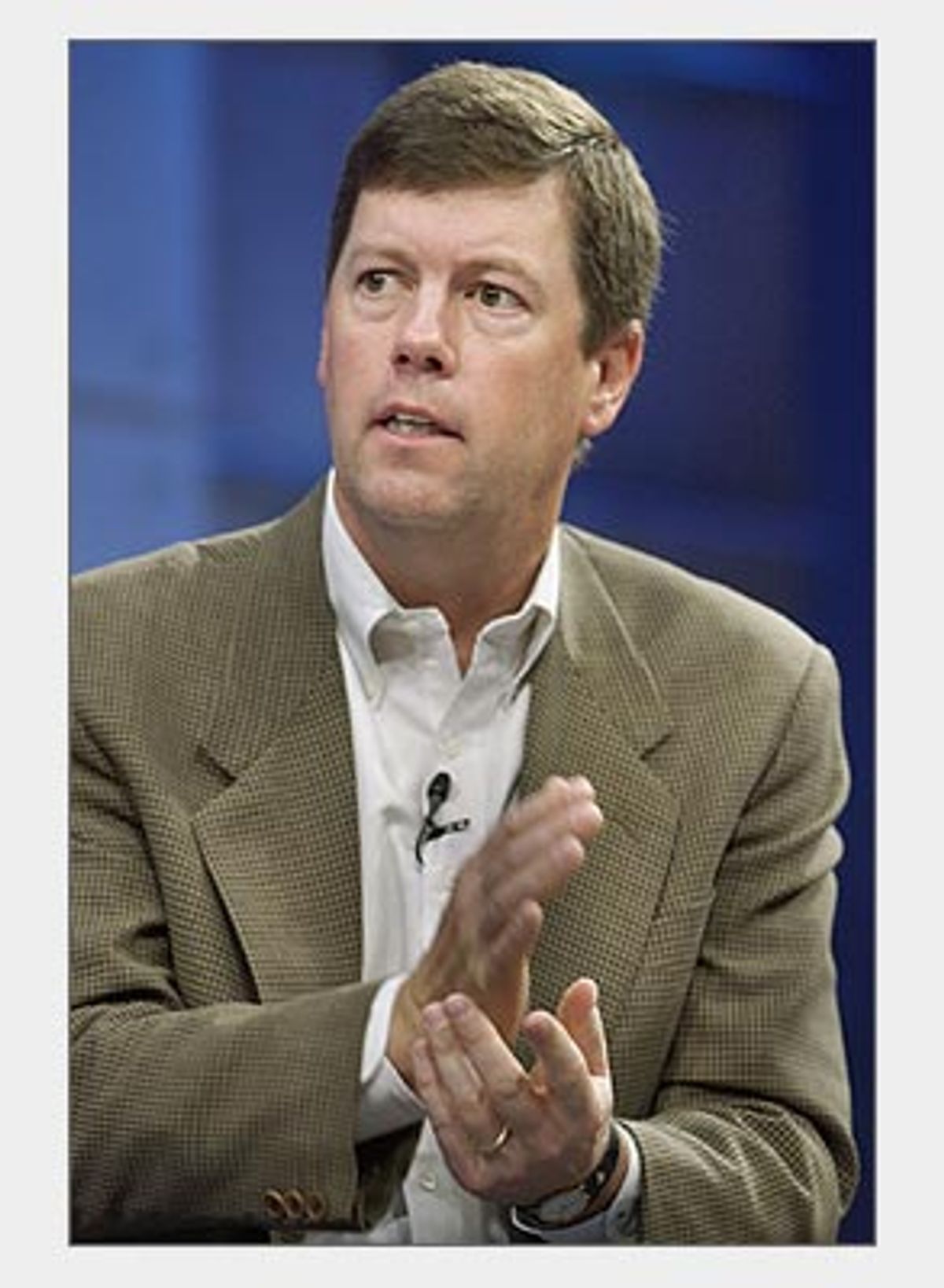

For those of us with experience selling complex products to corporate information systems departments, a comment made by Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy in a New York Times article published Monday says reams about what's going on in corporate America today.

McNealy was discussing a new requirement that CEOs attest to the accuracy of corporate financial statements.

"I haven't convinced myself that it is in the best interest of our shareholders," McNealy told the Times. To comply fully with the requirement, he explained, would mean attending quarterly meetings to close the books, usually chaired by the chief financial officer.

"That's what I'd be doing instead of being out here on the road, talking to customers and trying to generate more business for Sun," he said.

What investors should actually read McNealy as saying is: "My job as CEO of Sun is to be the chief pitchman, to glad-hand executives at my own level and convince them that Sun products are the right 'solutions' for their corporate needs. Determining whether the solutions actually work -- or whether it's even profitable for my company to sell them (and how would I know anyway?) -- is not my primary responsibility. In fact, if they don't work, or if our accounting is misstating our long-term profitability -- well, frankly, I resent the suggestion that I ought to have any legal accountability for my ignorance."

McNealy's attitude is the culmination of the last decade's ascendant ethos for U.S. business: near worship and lavish compensation for people who "make things happen" coupled with near contempt and minimal rewards for people who "make things work."

What "happened" is exactly what could have been expected: a tidal wave of scandal, corporate reverses, meltdowns and bankruptcies -- set to a chorus of denials from the people at the top that they had the slightest idea of the accounting, organizational and product "solution" deceptions on which the appearance of success was based.

Accounting scandals aside, another huge shoe is waiting to fall for many large organizations: many of the products and services supplied by companies offering "solutions" never worked, or never worked properly.

All of us are familiar, as individual consumers, with companies (and their leaders) who profited handsomely by arranging the purchase of their products by other, larger entities -- even though their products and services were ill designed or badly supported, sometimes even to the point of being, as a practical matter, useless.

What's less widely appreciated, except by the people who install and use them, is that many of the "productivity" solutions supplied over the last decade to U.S. businesses were broken.

They didn't work at all, or they worked worse than the systems they replaced, or (most frequently) they "worked" in only the sense that though they operated more or less as designed, they didn't work anything like the way were intended to work. Enormous amounts of human effort and ingenuity were required to keep accounting, management information, sales and distributions systems functioning at their previous productivity.

Many a CEO, or even a CIO, would be shocked to discover, were they to inquire (or encourage their subordinates to discover), that some of their employees are manually entering data (from two quarters back) into one system from printouts produced by another. Or that some 20 people buried in the customer service department do nothing, all day, but correct errors created when salespeople (after a half day's training) enter orders into a system so complicated and cumbersome that it takes weeks to train the people in customer service and accounts receivable delegated to picking up the pieces to use it properly. Or that out in the warehouse the complicated wireless system (which took years, not months, to really get working and cost four times what was budgeted) is randomly on the fritz, and stock must be picked manually several hours a day.

During the high-flying decade of the 1990s, CEOs sold each other such systems -- they "made it happen."

But the people who attempted to install and maintain such systems shrugged their shoulders, did the best they could, put each disaster and disappointment on their résumé as product experience, and moved on to the next job. And the rank and file worked double time to make it work.

In some cases the results were truly spectacular: the frequent inability of the newest, most brightly waxed order-fulfillment systems (installed without concern for cost by the best and brightest system integrators at burgeoning dot-coms) to get products onto the dock or shipped to the correct address, or to have them contain the right contents when they actually arrived, is one example.

The more common phenomenon was the company that stumbled through two, three or even four "systems" in the '90s -- declaring victory after each and moving on to the next system as each cadre of information systems management moved on to the next organization. From what I observed over a decade of selling and implementing such "solutions," such frustrations were typical.

The big picture is that some individual projects succeed, the occasional company does an effective (that is, productivity-raising) job of implementing such technologies, and some sorts of business activities (purchasing and inventory management, for example) respond well to such "improvement" -- but that on average, enormous amounts of time, money and corporate temper are wasted on attempts that subvert attention to more important business issues.

Every investor who reads the newspaper understands in principle that most businesses supplying such "solutions" are in a deep recession right now.

What I believe is not so generally understood is that -- as their business customers take a long, hard look at the results of efforts to implement such solutions over the last decade -- the claims of vendors are going to be subjected to much more sober evaluation.

So where does this leave McNealy?

I am no longer close enough to the business to know where Sun's products rank against the competition.

But the Scott McNealys of the world, considered generically, have for at least a decade thrived as heads of a fool's paradise, installing regimes of benign neglect in which ignorance and self-delusion regarding the quality of their products has often gone hand in hand with the inflation of earnings via accounting chicanery.

At the moment getting a handle on both sorts of corporate self-deception is not only "in the shareholders' interest"; it's arguably also the most important function a CEO can perform for the stockholders.

McNealy, it appears, sees it differently. He told the Times that "many of the executives he talked with are equally concerned about the trend toward what they regarded as ill-considered regulation and a rising anti-business attitude. But few of them have said so publicly."

"My fellow CEOs are rolling over, paws-up, on this," McNealy lamented to the reporter. "And I think that is a mistake."

He can probably, out there on the road, sell that to many of his fellow CEOs.

I wonder if he can sell it to his investors.

Shares