When the Belgian DJ duo 2ManyDJs were creating their own album of "bootlegs" -- hybrid tracks that mix together other people's songs to create new songs that are at once familiar yet often startlingly different -- they decided to get permission to use every one of the hundreds of tracks they mashed together. The result: almost a solid year of calling, e-mailing, and faxing dozens and dozens of record labels all over the world. (Creating the album itself only took about a week.) In the end about a third of their requests were turned down, which isn't surprising. Many artists and their labels have become reluctant to allow any sampling of their work unless they are sure the new work will sell enough copies to generate large royalty checks.

What is surprising are the names of some of the artists who turned them down: the Beastie Boys, Beck, Missy Elliott, Chemical Brothers, and M/A/R/R/S -- artists whose own careers are based on sampling and who in some cases have been sued in the past for their own unauthorized sampling. For whatever reason these artists decided not to license their material, the net effect is that more entrenched, "legitimate" sampling artists are preventing lesser known, struggling sampling artists from doing what the legitimate artists probably wish they could have done years ago: sample without hindrance to create new works.

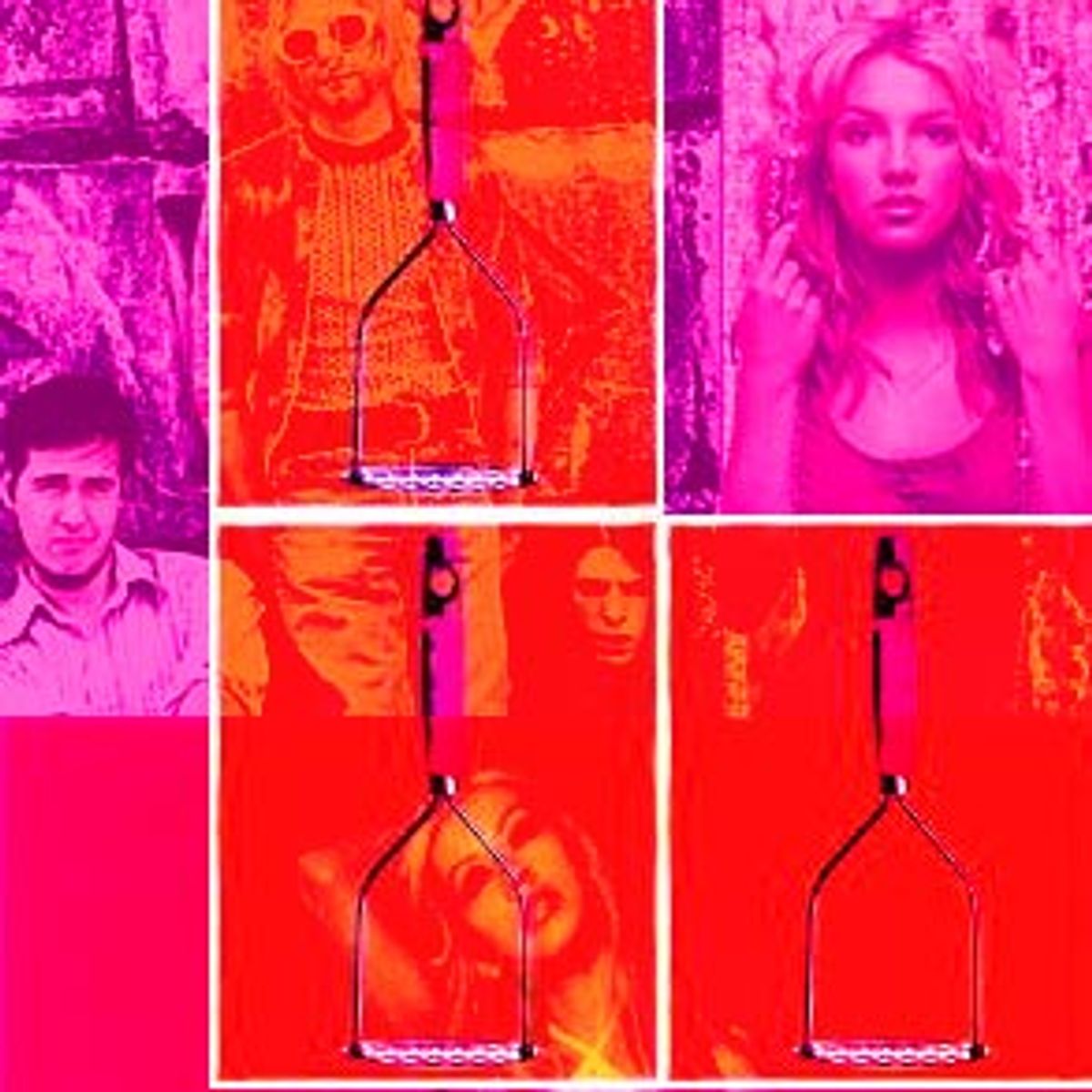

Typically consisting of a vocal track from one song digitally superimposed on the instrumental track of another, bootlegs (or "mash-ups," as they are also called) are being traded over the Internet, and they're proving to be a big hit on dance floors across the U.K. and Europe. In just the past couple of years, hundreds if not thousands of these homebrewed mixes have been created, with music fans going wild over such odd pairings as Soulwax's bootleg of Destiny's Child's "Bootylicious" mixed with Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit," Freelance Hellraiser's mix of Christina Aguilera singing over the Strokes, and Kurtis Rush's pairing of Missy Elliott rapping over George Michael's "Faith." Bootlegs inject an element of playfulness into a pop music scene that can be distressingly sterile.

While there have been odd pairings, match-ups and remixes for decades now, and club DJs have been doing something similar during live sets, the recent explosion in the number of tracks being created and disseminated is a direct result of the dramatic increase in the power of the average home computer and the widespread use on these computers of new software programs like Acid and ProTools. Home remixing is technically incredibly easy to do, in effect turning the vast world of pop culture into source material for an endless amount of slicing and dicing by desktop producers.

So easy, in fact, that bootlegs constitute the first genre of music that truly fulfills the "anyone can do it" promises originally made by punk and, to lesser extent, electronic music. Even punk rockers had to be able write the most rudimentary of songs. With bootlegs, even that low bar for traditional musicianship and composition is obliterated. Siva Vaidhyanthan, an assistant professor of culture and communication at New York University and the author of "Copyrights and Copywrongs," believes that what we're seeing is the result of a democratization of creativity and the demystification of the process of authorship and creativity.

"It's about demolishing the myth that there has to be a special class of creators, and flattening out the creative curve so we can all contribute to our creative environment," says Vaidhyanthan.

The debate over what bootlegs are and what they mean is taking place within the wider context of a culture where turntables now routinely outsell guitars, teenagers aspire to be Timbaland and the Automator, No. 1 singles rework or sample other records, and DJs have become pop stars in their own right, even surpassing in fame the very artists whose records they spin. Pop culture in general seems more and more remixed -- samples and references are permeating more and more of mainstream music, film, and television, and remix culture appears to resonate strongly with consumers. We're at the point where it almost seems unnatural not to quote, reference, or sample the world around us. To the teens buying the latest all-remixes J.Lo album, dancing at a club to an unauthorized two-step white-label remix of the new Nelly single, or even hacking together their own bootleg, recombination -- whether legal or not -- doesn't feel wrong in the slightest. The difference now is that they have the tools to sample, reference, and remix, allowing them to finally "talk back" to pop culture in the way that seems most appropriate to them.

The recording industry instinctively fears such unauthorized use of copyrighted materials. But instead of sending out cease-and-desist orders, it should be embracing bootlegs. In a world of constantly recycled sounds and images, bootleg culture is no aberration -- it's part of the natural evolution of all things digital.

Bootlegs don't contain any specific audible element of originality in the track, in the sense that one can identify any specific original vocal or musical composition created by the remixer. The only original element of a bootleg is the selection and arrangement of the tracks to be blended into a new work. Scottish bootlegger Grant Robson, who goes by the name Grant McSleazy, responsible for such tracks as Missy Elliott versus the Strokes, readily admits this: "There is a creative aspect, because not all songs work well together, but all the lyric writing and music composition has been done for you. You may rearrange the segments of an instrumental/a capella, but that's just production work."

Even so, isn't production work what constitutes most of what goes into crafting most hip-hop, electronic music, and pop these days? Because of this, bootlegs highlight the increasing difficulty in distinguishing between musicians, DJs and producers. Is there really all that much difference, on a technical level, between McSleazy, DJ Shadow, Moby and P. Diddy? Putting aside any qualitative judgments, on one level or another they are all just appropriators of sound. They are all combining elements of other people's works in order to create new ones, in effect challenging the old model of authorship that presupposes that the building blocks of creativity should spill forth directly from the mind of the artist.

Already we've seen that our notion of what makes a song "creative" has widened in the case of hip-hop. Early on, hip-hop -- constructed largely with snippets of other songs -- faced similar charges that it lacked a creative element. Eventually, because a great deal of arrangement is involved (usually a large number of samples are blended together to create just a single hip-hop track), and because the rapping itself contributes an original element, pop culture at large has found it easier to acknowledge some aspect of originality and creativity within hip-hop. Bootlegs challenge this notion even further, but it is almost inevitable that as they grow in popularity, something similar will happen, and our definition of creativity will expand to accommodate them.

Existing copyright laws mean that, for the most part, this movement will remain underground. Consequently bootlegs may be the first new genre of music that is almost entirely contraband, and most bootlegs now can only be found on a few Web sites or on file-sharing networks like KaZaA and Gnutella. The bootleggers behind these audio mismatches know they will never get permission from the artists they sample and haven't even bothered to try to get it. Though 2ManyDJs tried to go legit and get permission for as many songs as possible, they still were unable to get clearance for a significant number of samples they used on their album -- and even the permissions and clearances they do have are so restricted that it will be impossible to release the album in the United States. Despite the tremendous amount of energy poured into these desktop productions, the fact remains that because the original works cut and pasted together are used without the original artists' permission, bootlegs have stayed, well, bootlegs.

While everyone (particularly the companies touting the technologies that make all this possible) predicted a flood of original movies and music spewing forth from the desktops of bedroom auteurs, no one anticipated that large numbers of people would be more interested in using their computers to combine, mash together, or remix other people's work. Sharing one's unauthorized creations via the Net is even easier. It's a dramatic change from just a few years ago, when a bootlegger's sole option would have been to have vinyl or CDs manufactured and then distributed, something that would risk arousing the attention, and legal action, of the record labels of the remixed artists.

This phenomenon hasn't been limited to music: Remixing has begun to infect film as well. Last year copies of a home-edited version of "Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace" began circulating on the Internet to widespread acclaim from fans who declared "Star Wars Episode 1.1: The Phantom Edit" the superior of the two versions. It's probably only a matter of time until someone creates a fan edit of "Attack of the Clones." Inspired by the "Phantom" edit, DJ Hupp, a freelance film editor in Sacramento, Calif., has created his own "Kubrick edit" of Spielberg's "A.I.," and it is unlikely that his will be the last fan edit we see of a major motion picture.

Such fan edits are also, technically, illegal, but from the perspective of the turntablists, remixers, and home editors at the forefront of the explosion of bootleg culture, copyright laws don't look like anything other than the means by which one group of artists limits the work of another.

Illegality can actually be a large part of the allure of bootlegs. Much underground cultural expression takes place at the margins of the law -- rave culture, for example, has its origins in illegal warehouse parties. Using other people's music without permission used to be the point of mash-ups. Back in the '80s and early '90s, when culture-jamming sound collagists like Negativland and the Evolution Control Committee released their first works, mash-ups had a decidedly subversive edge to them. Mash-ups were typically created as statements about pop culture and the media juggernaut that surrounds us, not as fodder for the dance floor. Pasting together elements swiped from the top 40 and placing them together in a new form was supposed to snap us out of what these sonic outlaws saw as our media-induced trance and make a point about copyright in the process.

Traces of that element remain in the bootlegs being made today. One Australian bootlegger, a 26-year-old who goes by the name Dsico, and for legal reasons prefers that his identity be withheld, sees bootlegs as akin to the kitschiness and pastiche of pop art. "The reinterpretation and recontextualization of cultural icons like Britney Spears or the Strokes is fun and good for a laugh. But if I can grab an a cappella track of Mandy Moore and mix it with something like "Roxanne" by the Police, while that juxtaposition may be trite, it still works as a commentary on pop music today."

And at a time when it has become increasingly difficult for pop music to be shocking (witness the mainstream acceptability, however grudging, of Eminem), it may be that the only way to write a transgressive pop song is to flat-out steal it from someone else. In other words, the only way left to shock is not through controversial content, but by subverting the very form and structure of the song itself.

Even though making music out of other people's songs without permission may appear to pose a threat to the business model of the recording industry, killing off this nascent genre may not ultimately be in the industry's best interests. Radio stations in Britain that have played bootlegs have found themselves on the receiving end of cease-and-desist orders. Hip-hop got its start using pre-existing music in innovative and not always legal ways. It is arguable that had the music industry clamped down on sampling earlier than it did (it wasn't until a 1991 suit against rapper Biz Markie that sampling without permission was established as illegal), the industry's top-selling genre would never have gotten off the ground commercially. Now legendary hip-hop albums, such as Public Enemy's "It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back," and the Beastie Boys' "Paul's Boutique," would be impossible to release today.

Just as with every other subcultural movement that has threatened the status quo, the music industry's best response may be to let the genre flourish online and on the margins. So far no one is really making any money from bootlegs, -- if anything, bootlegs stimulate demand for the original songs. Rather than threaten bootleggers with legal action, a sounder strategy would be to co-opt the scene by skimming the best ones off the top and re-releasing them as "official" bootlegs. This has already produced one No. 1 hit, with Richard X's mash-up of new waver Gary Numan and soul singer Adina Howard. The track follows in the footsteps of DNA's bootleg dance remix of Suzanne Vega's "Tom's Diner," which Vega ended up authorizing and re-releasing to much chart success in 1990.

As computers and software programs get more and more powerful with each passing year, as file-sharing networks make it simple for anyone to share their work with the world, and as it is next to impossible to outlaw digital editing software (which has plenty of legitimate uses), bootlegs and remixes will likely be a part of the cultural landscape for years to come. Bootlegging may even evolve into something of a hobby for tens of thousands of desktop producers who will spend their free time splicing together the latest top 40 hits for kicks, like model-airplane builders. The record industry could even respond by selling its own do-it-yourself bootleg kits, complete with editing software and authorized samples. In a sense bootlegs are music fans' response to the current disposability of pop culture. Effortlessly easy to create, with an infinite number of combinations possible, bootlegs are even more perfectly disposable than the pop songs they combine -- by the time the novelty and the cleverness have worn off there will always be new hit singles to mash together.

Eventually recombining and remixing is likely to become so prevalent that it will be all but impossible to even identify the original source of samples, making questions about authorship and origins largely irrelevant, or at least unanswerable. We're already seeing the beginnings of that, like the hip-hop song that samples an older hip-hop song that samples a '70s funk song. Some artists, most notably David Bowie, are already proclaiming the death of authorship altogether. Technology has not only expanded who can create; in blurring the distinction between consumers and producers, these new digital tools are also challenging the very ideas of creativity and authorship. They are forcing us to recognize modes of cultural production that often make it impossible to answer such once simple questions as, Who wrote this song? The cultural landscape that emerges will be a plural space of creation in which it may even become pointless to designate who created exactly what, since everyone will be stealing from and remixing everyone else. The results might be confusing, but it'll probably be a lot more fun and worth listening to than a world where only those with the financial resources to pay licensing fees (e.g., P. Diddy) get to make songs with sampling.

Shares