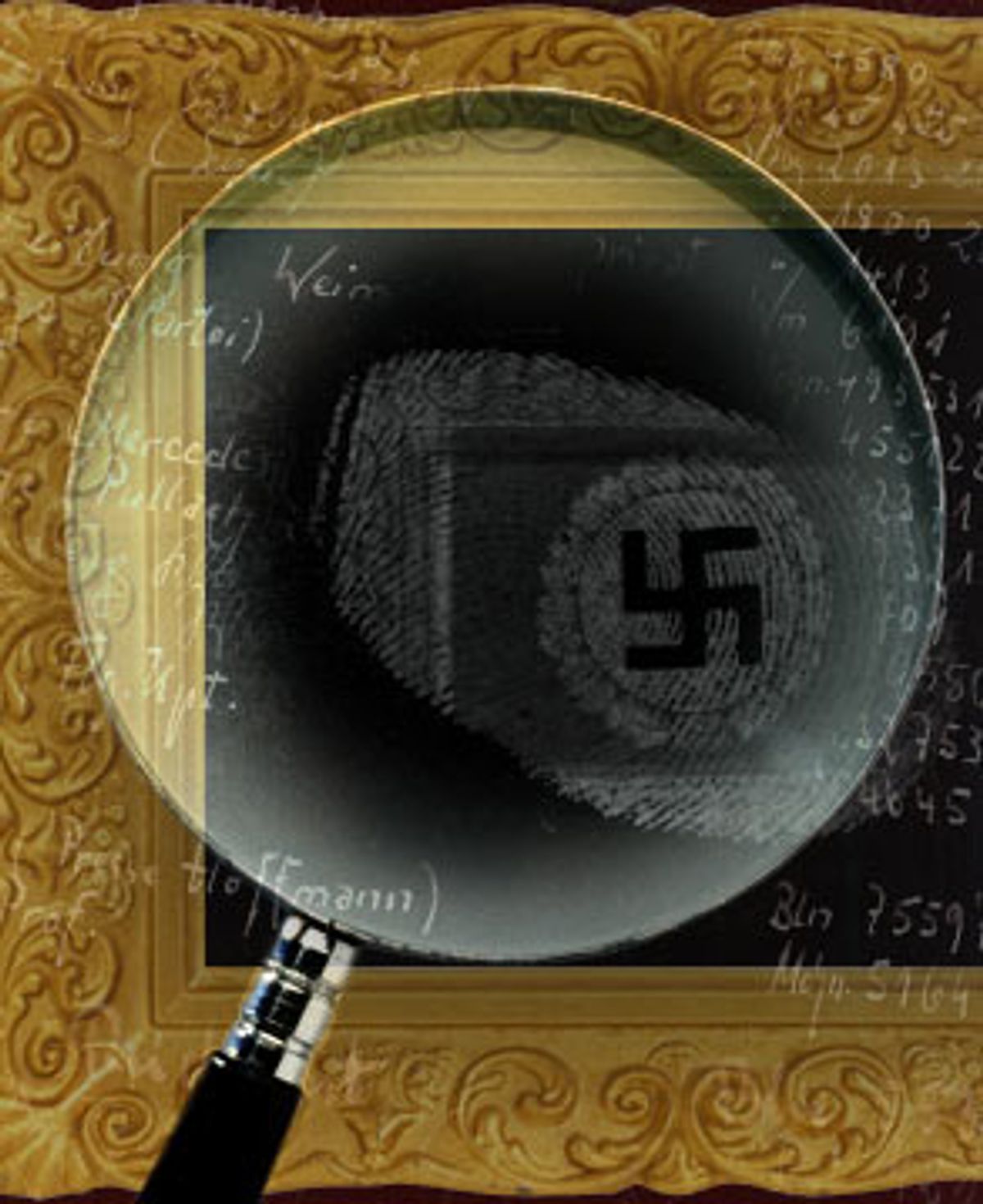

When the Nazis pillaged tens of thousands of artworks from museums and private collectors in occupied countries during World War II, they didn't just take the loot, they took notes.

The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, a major S.S. art-plundering organization, documented their haul on 5-by-8 index cards, meticulously describing each work. A typical ERR index card might include the name of the piece, its dimensions, the artist, scholarly notes on the significance of the work, and where and from whom it was stolen, says Sarah Kianovsky, assistant curator at Harvard University Art Museums.

"One of the terrible things about the Nazis is that they kept these extensive records about what they had taken," says Derrick Cartwright, director of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. "It was so systematic that there is this archival legacy."

That chilling legacy is now finding its way online, at sites like the National Archives and Records Administration. The goal is to provide new access to the history of ownership, known as "provenance," of some of the millions of art objects and cultural artifacts stolen during Nazi looting.

No one knows how many of the items are still at large. Museum curators still pore through these Nazi records, auction catalogs and bills of sale, as well as the documentation of Gestapo treasure-troves compiled by Allied forces, in an ongoing attempt to reconstruct the paths works of art took before they landed in their collections.

American museums now think that the Web can help in their attempt to uncover the Nazi loot that may still be hanging on their walls. In September 2002, the American Association of Museums received a $240,000 grant from the federal Institute of Museum and Library Sciences for the creation of a Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal: a registry of objects in American museums of questionable ownership.

According to one theory, the U.S. Defense Department funded the early Internet because it hoped a distributed network would help protect American computer systems in case of some future nuclear attack. Now that network is being deployed to investigate the unsolved war crimes of World War II. Rather than protecting military secrets from a future threat, it's being used to help unravel a more than 50-year-old art theft mystery. The Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal isn't the first online attempt to address the question of artworks stolen by the Nazis. The German government already maintains a Lost Art Internet Database, where museums can register questionable objects for claimants to search. More than a dozen U.S. museums also have made information about objects in their collections, which have gaps in their histories of ownership, available online.

But the Provenance Portal aims at consolidation. "We're hoping to provide one central point where the descendant of a Holocaust victim could go," says Edward Able, the president of the American Association of Museums, who compares the task of finding a stolen artwork to "looking for a needle in a haystack."

"This is an effort to centralize the process," he says.

The Provenance Internet Portal aims to take advantage of the Internet's primary function: distributing information.

"It's so much like genealogical research," says Derin Basden, manager of the Provenance Index at the Getty Research Institute. "You have to dig and find records, and both sciences are really expanding because of the Internet."

For many museums, art provenance during the Nazi era has taken on new urgency in recent years. Since the reunification of Germany and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, thousands of new records have become available to scholars. Now that more than 55 years have passed since the end of the war, many documents in American archives have become newly declassified. The new primary source material and a number of well-publicized scandals in the late '90s, involving the Art Institute of Chicago, the Seattle Art Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which Nazi-looted art was found in American collections, galvanized museum curators to try to ferret out possible contraband before a family seeking restitution comes along.

For curators, there's a stigma to having unknowingly acquired or harbored the looted goods. "If it went through Nazi hands, you're basically saying you're a Nazi collaborator. That's the feeling in the museum community," says Basden of the Getty, adding quickly: "You're not, of course. But it reflects badly on the curator who selected the painting. You've not only lost money that's been invested in the painting, you've lost face in the community."

In November 1999, the American Association of Museums called on its members to investigate the history of any art in their collections that was created before 1946 but acquired by the museum after 1932, underwent a change of ownership between those dates and was likely to have been in continental Europe at the time. Museums were also asked to make information about objects of questionable provenance available on the Web.

Under these criteria, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth is investigating the origin of 100 objects of questionable provenance, out of a collection of 60,000, according to Cartwright.

Sarah Kianovsky at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard is studying the provenance of about 400 paintings there, while Harvard University Art Museums at large has a total of 6,000 artworks to look into.

The restitution game is complicated by the fact that the rightful owners of these objects may have been children when the painting or sculpture in question was lost, and may never have known the official title of the piece or the name of the artist. Descendants of Nazi victims may not know exactly what they're looking for.

"Just because someone's grandmother says that the family had a Renoir, it might not have been a Renoir," says Kianovsky.

And while it's hard for a layperson to make sense of primary source material, the opening of more records to the public on the Web could lead to more false claims. "A lot of the claimants are lying," says Basden. "But sometimes they're not." Despite the chance of fraud, museums still take accusations of harboring stolen goods seriously when the "N" word is invoked: "Once you say 'Nazi,' everybody runs. It's like 'shark,'" says Basden.

Can the Web really help sort through the Gestapo's cultural blitzkrieg? So far, the Net has already helped lead to the restitution of at least one painting.

In November 2000, the National Gallery of Art announced that the 17th century painting "Still Life With Fruit and Game" by the Flemish artist Frans Snyders would be restored to its rightful owners, after information about the history of the ownership of the painting appeared on its Web site.

The painting was confiscated from the Stern family collection in Paris by Hermann Goering, the second-in-command of the Third Reich, known for his taste for European painting.

The records of Goering's pillaging will be online in the Getty Research Institute's Provenance Index next year, along with some 1 million art-ownership documents already digitized there. And hidden in those records of the Nazis' historic crimes will be clues that an Internet-era art sleuth could use to bring a work home.

Shares