On May 28, in a ceremony in the East Room of the White House, President Bush signed into law the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, the second major tax-cut bill of his presidency. The plan, which carries an official 10-year price tag of $350 billion but is likely to cost several times as much, has come under heavy criticism from Democrats and some Republicans, but as he signed the bill Bush insisted it would revive the U.S. economy.

The mechanism, as he outlined it, seems simple: The new tax cuts, Bush said, will let Americans keep more of "your own money." And "when people have more money, they can spend it on goods and services. And in our society, when they demand an additional good or a service, somebody will produce the good or a service. And when somebody produces that good or a service, it means somebody is more likely to be able to find a job."

As the United States' economic doldrums continue, evaluating whether Bush's tax cuts make sense becomes an increasingly pressing task. The Dow may be rising, but employment is continuing to fall. Deflation is possible. The dollar is weakening. Local and state governments are beset by their own deficits, while the federal debt is ballooning at an astounding rate -- on Tuesday, the Congressional Budget Office warned that the federal government is headed for a record $400 billion deficit in 2003. And, perhaps most critically, there is a massive financial crisis looming on the horizon: the budget bomb caused by huge Social Security and Medicare benefits that will be paid out to retiring baby boomers beginning in 2008.

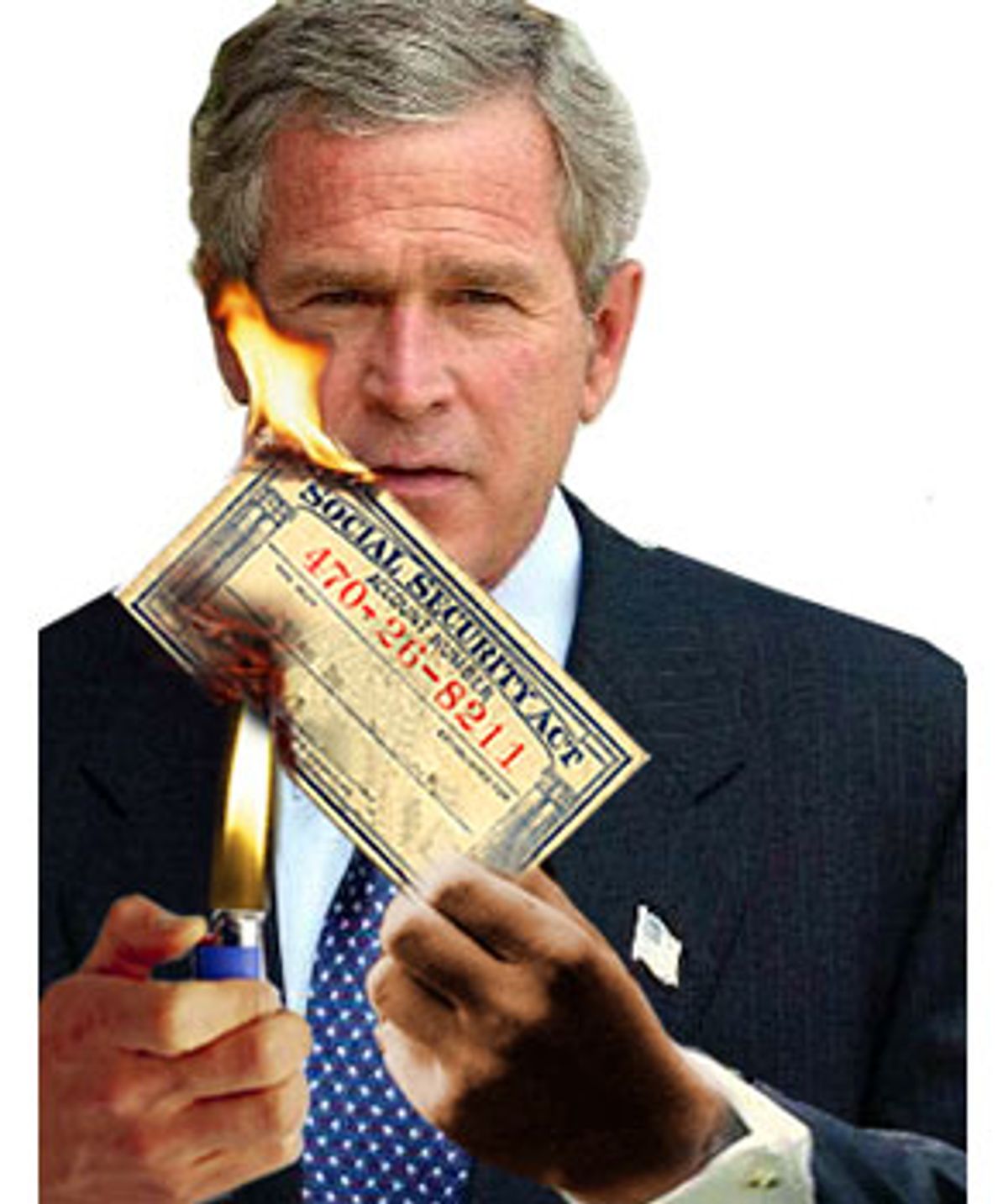

The White House says that supply-side tax cuts will cure all of our economy's problems, but a look at the record of such cuts in the Reagan years suggests just the opposite. Indeed, to many observers, a relentlessly executed program of tax cuts seems designed to accelerate a Social Security catastrophe, not avoid it.

Even staunch conservatives are beginning to express doubts. In the New York Times Magazine on Sunday, Peter Peterson, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Richard Nixon's commerce secretary, noted that under Bush the Treasury has turned $5.6 trillion of projected surpluses into an estimated deficit of $4 trillion.

"Since 2001, the fiscal strategizing of the party has ascended to a new level of fiscal irresponsibility," Peterson wrote. "For the first time ever, a Republican leadership in complete control of our national government is advocating a huge and virtually endless policy of debt creation."

A charitable explanation of why Bush is still pushing tax cuts is that it's all he knows how to do: It's his one policy, and by God he's sticking to it. But there's another, perhaps more convincing rationale: the argument that Bush's deep, permanent cuts are in the service of a central conservative political goal, an eternally hobbled federal establishment.

Such a strategy was attempted before -- during the Reagan years, but even then, a huge tax cut was soon followed by several tax increases. Such a course correction seems increasingly unlikely in the current political climate. Bush's policies will prevail long after he's gone. There will be precious little money for social programs, or environmental protection, or homeland security. And if Democrats want any of these things, they'll face a stark choice: They can ask for tax increases and commit political suicide. Or they can give in to what may be Bush's main reelection plank, using the coming baby boomer retirement disaster as an excuse for privatizing Social Security.

There are several ways to measure the "size" of the president's tax cut plan. Officially, when all its provisions have been fully phased in, the plan will drain about $350 billion from the treasury between now and 2013 -- which is itself not a small amount, considering what else that money might have purchased. The $350 billion price tag, though, is smaller than the president's initial $726 billion proposal and the House's $550 billion plan.

The relatively smaller size of the tax cuts enacted into law is something of an optical illusion, however. Thanks to some skillful budget trickery, Bush's tax cut is still a massive cut, albeit squeezed into a (relatively) small package. In order to keep the advertised 10-year price under the $350 billion limit, Republicans allowed many of its provisions to "sunset," or expire, before 2008.

But if the Republicans continue to control Congress and the presidency, it is likely that many -- or all -- of these provisions will be extended. In that case, the bill's 10-year price would be between $807 billion and $1.06 trillion, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Conservatives make no apologies for the sunset gimmick. Grover Norquist, the head of Americans for Tax Reform and a close friend of the Bush White House, calls the tax cut "a thing of beauty" and says that the moderates and Democrats got what they deserved for putting an arbitrary cap on tax cutting.

Besides, according to Bush, the tax cut is the key to sparking new growth and creating millions of new jobs. During his speech at the bill-signing ceremony Bush said the word "jobs" about a dozen times. It's obvious why. During his time in office, about 2.7 million people have lost their jobs. The White House projects that the new tax cut will create 1.4 million new jobs, but, as many Democratic lawmakers note, that would still leave Bush the only president since Herbert Hoover to have presided over a job-losing economy. (Interestingly, Hoover, too, was aided by a Republican-controlled Congress.)

The idea of giving Americans spending money to help the economy "get a good wind behind it" does not, strictly speaking, conform to bedrock Republican theories of how economies ought to function. Conservative economists ("supply-siders") do not generally believe that output grows simply because people have more money to buy things -- if they thought so, they'd support government welfare.

Instead, many conservatives -- including the president's advisors -- think that real growth occurs only when people react to lower tax rates by working harder or by investing more. What's striking about George W. Bush is that in two years of selling some of the largest supply-side tax cuts in history, he's hardly ever made that case. Indeed, he's never made any single coherent argument for "tax relief." Instead, since his campaign, he's constantly tailored his pitch to fit the prevailing political mood. As the New York Times reported on Feb. 5, 2002, "He has argued that tax cuts are necessary when the nation is flush with prosperity and when it is in the economic dumps, in peacetime and in wartime, to get rid of the budget surplus and to restore it."

For jobs to be created, the economy would have to grow, and there is plenty of dispute about whether this tax cut will make that happen. In a paper he wrote in March, Richard Kogan, an economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, noted that Macroeconomic Advisers, an economic consulting firm, determined that in the long run, the president's package as it was initially proposed would reduce economic growth.

The assessment by Macroeconomic Advisers, Kogan wrote, "is especially significant because the President's Council of Economic Advisers uses the economic model that Macroeconomic Advisers developed." The firm said that at first, "the plan would stimulate aggregate demand significantly by raising disposable income, boosting equity values, and reducing the cost of capital." But because of its huge cost, the plan also reduces national savings, which will lead to increasing interest rates. "By 2017 the effect would be to reduce the level of potential GDP by about 0.3 percent and raise long-term interest rates by about 0.75 percentage points."

When asked about such models, conservatives often dismiss them and point to the Reagan years, when, they say, tax cuts led to strong economic growth. But a close look at the Reagan years doesn't support their claims. In the '80s, the postwar decade in which the United States enjoyed the lowest marginal tax rates, economic growth averaged about 3.2 percent per year. The trouble is, as Kogan points out, that such growth was not all that much better than growth in other decades. In the '90s, for example, a decade in which marginal taxes were raised and the United States experienced record surpluses, economic expansion averaged 3.1 percent a year. When you adjust for the population differences between the two decades, the growth per person in the 1980s is identical to that of the 1990s. The '70s, too, had similar growth -- about 3 percent. In other words, for all the conservative reverence for Reaganomics, the strategy two decades ago does not appear to have added any significant boost to the economy -- which makes it curious that the Bush administration is still pushing the same plan, especially when you think about the endless deficits it will entail.

Unless endless deficits are the goal.

Asked whether he was worried about deficits, Norquist said, "Deficits are driven by how much money the government spends. If you're worried about the deficits, cut spending. People who say they're worried about deficits are actually just against cutting taxes."

The main refrain of conservatives when it comes to deficits is something like a pro-gun rant: Tax cuts don't cause deficits, people do. If you're concerned about deficits, reduce spending, and you'll be fine.

There are a few problems with this formulation. First, it's not easy to cut spending, mostly because, despite what you hear on TV, there really is no evidence that the federal government is a profligate spender. The Congressional Budget Office provides a nice picture (as these things go, at least) of past and likely future federal spending in its report "A 125-Year Picture of the Federal Government's Share of the Economy, 1950 to 2075." One of the charts in the report shows various types of federal spending represented as a percentage of total economic output in the years spanning 1962 to 2001.

During those years, "nondefense discretionary" spending -- which does not include federal spending for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid but does include spending on all of the programs Republicans love to pillory as a waste of taxpayer money, such as Head Start -- remains more or less constant. In 1962, nondefense discretionary spending is 3.4 percent of the GDP. And, lo, in 2001, it's also 3.4 percent of the GDP. There are a few years when federal spending rises much higher than that -- in 1975, it hit 4.5 percent, and in 1980 it reached 5.2 percent. Mostly, though, spending doesn't seem out of control; it's not, at the very least, ballooning into unmanageability.

According to the CBPP, Bush's new tax-cut plan will reduce federal revenues to as low as 16.4 percent of the GDP in 2003 -- the lowest level since 1959, and about 1.5 percentage points lower than what was collected last year. In order to cut current discretionary spending to meet the new tax cut, then, outlays would have to be reduced from 3.4 percent of the economy to only 1.9 percent. This would represent more than a 40 percent cut in all federal discretionary spending -- obviously impossible in a time of monthly orange alerts.

There's no sign that Congress or the White House is willing to cut spending so drastically. Again, the Reagan years are instructive on this matter. Reagan's tax cuts reduced federal revenues from 19.6 percent of the GDP in 1981, to 17.4 percent in 1984, the lowest point during his presidency. From 1984 to 1988 revenues increased slightly -- to 18.1 percent of the economy in Reagan's last year.

Did this reduction in revenues cause lawmakers to reduce spending? Not a bit; spending shot up in the Reagan administration. Some of this was due to increased discretionary spending, and some due to a nudge up in spending for mandatory programs like Social Security and Medicare. But the real budget buster, especially during Reagan's later years and for most of the first Bush administration, was the interest on the federal debt. In 1991, for example, the interest on the debt constituted 3.2 percent of the economy -- about as big a share as is now spent on national defense. In 1983, the federal government spent an amount equal to 23.5 percent of the GDP, the zenith in government spending of the last 40 years.

The Clinton years, by comparison, are a veritable model of discipline. In 2000, the federal government spent money equal to 20 percent of the GDP; this was the lowest level of government spending since the Johnson administration. Republicans note that Clinton was helped out greatly by peace, which reduced the need to spend on defense. That's true. But Clinton also benefited from a steady reduction in interest payments on the debt, which Clinton (and Gore, and George W. Bush) had pledged to pay off by the end of this decade (that goal is now off the table).

It's also interesting to note that since Bush took office, discretionary spending (defense and nondefense) has slowly edged up as a share of the economy. In 2002, discretionary spending was 7.1 percent of GDP; it was 6.3 percent in 2000.

Reagan's deficits were bad, but there was one silver lining to them -- the country had a few decades to go before things really turned sour. We don't have that grace period anymore. In 2008, the people born in 1946, the first year of the baby boom generation, will turn 62 and begin collecting retirement benefits. This will mark the onslaught of a demographic shift that promises to have profound implications for the nation: Entitlement obligations will shoot through the roof while, at the same time -- because fewer people will be working and because of the recent tax cuts -- the federal government will have much less money streaming into its coffers. According to modest measures, Social Security and Medicare will accumulate $25 trillion in debt over the next 75 years, but some analysis has it much higher than that, and if you look beyond the 75-year window the number can double or triple.

The Congressional Budget Office has this crisis all mapped out on its Web site in a series of briefs that go by nervous-sounding titles like "The Looming Budgetary Impact of Society's Aging" and "Social Security and the Federal Budget: The Necessity of Maintaining a Comprehensive Long-Range Perspective." The CBO probably feels it needs to keep reminding lawmakers of the upcoming problem. While the entitlement crisis has been a hot political issue in the past -- it came up during the 1992 presidential election, with Ross Perot staging TV teach-ins using colored bar-graphs -- few politicians have taken the risk of addressing the problem.

That changed in the late 1990s, when the federal budget went into surplus. People who follow Social Security often cite Bill Clinton's 1999 State of the Union address as the watershed event in this debate. That year, Clinton was the first president since Nixon to have had the convenient problem of deciding what to do with extra money in the Treasury. The Republicans, who controlled both houses of Congress, were pushing for tax cuts -- a surplus, they reasoned, meant that the government was taking in more of the people's money than it needed, so it ought to give some back. Clinton, though, apparently following the CBO's advice, was looking at the long term. "First and above all, we must save Social Security for the 21st century," Clinton said. He proposed spending more than half of future surpluses to bolster Social Security finances, and another 15 percent for Medicare.

In the 2000 election, the entitlement programs became a main domestic policy concern for voters. A Pew poll conducted in October of that year shows that the issue edged out education as the thing that most concerned Americans. Gore made Social Security and Medicare his campaign rallying call, though he did so with notorious awkwardness. In the first presidential debate, Gore tried to interest Americans in the strange budgetary animal known as the "lockbox." (Currently, Social Security is running a surplus, so Gore wanted to ensure, via some kind of legislative mechanism, that the government was permanently prevented from raiding that surplus to meet other, more pressing spending needs.)

Bush declined to sign on to the lockbox idea. But during his campaign Bush did promise not to spend entitlement money on his tax cut. During his Senate confirmation hearing, Paul O'Neill, Bush's first Treasury secretary, said: "There is room to fit the president-elect's tax proposals into even the low end of the economic assumptions and growth rates that I've looked at without touching any Social Security money. This is -- for him, this is an inviolate principle."

But shortly after Bush's first tax cut was passed, the lockbox was broken. Bush likes to say that terrorism, war and corporate scandals have contributed to the rising deficits, but it was in August 2001 that the CBO first predicted that, in the following fiscal year, federal surpluses would be exhausted and that several billion dollars from Social Security would need to be tapped. In effect, what this means is that the Social Security Administration is lending the Treasury money to run the government. In return for its generosity, the SSA gets special bonds from the Treasury Department representing the money it has given up. These bonds, says David John, an economist at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative Washington think tank, are stored in a special safe at the Bureau of Public Debt in Parkersburg, W.V., and add up to what's known as the "Social Security trust fund." The trust fund is now valued at almost $1.4 trillion. "It's a fireproof safe," says John.

The Social Security "crisis" is predicted to really begin in 2018, when, for the first time, the money the government takes in from Social Security taxes will not be enough to pay for Social Security benefits. At that point, the Treasury will dip into general funds to pay benefits. As a matter of accounting, the Treasury will be giving back the money it borrowed from the SSA, and the SSA will hand in those bonds it has been collecting. But since the Treasury is spending that money now, it will have to borrow the money from someone else. And SSA's bonds will run out in 2041, at which point Social Security will have enough money to pay beneficiaries only three-quarters of what's due to them.

"This is literally the case of knowing that your property taxes are due in November and in January or February you're spending it on other things," John says. "That's going to make November really hard."

Conservatives are right to say that Gore's lockbox would not have solved the Social Security crisis; he was talking about piling up several trillion dollars when what we need is tens of trillions. John, who favors the Bush tax cuts, says, "What he was doing was like paying off your Visa bill knowing that you're going to max off your Visa card again for Christmas." The lockbox didn't do anything to help the long-term health of Social Security -- but it might have provided enough of a cushion to stave off the crisis and figure out some other ways to solve the problem. The Democrats were following what might be called a common-sense rule of budgetary accounting: When you find yourself in a hole, stop digging. Save up your money. The Republicans, on the other hand, want to dig some more on the off chance they may unearth some supply-side pot of gold.

Are the Republicans stupid? Is the White House advocating policies that have been shown to be both useless and reckless simply because Republicans have no weapon in their economic arsenal other than ever larger tax cuts? For many on the left, it's tempting to think so, but that's probably not the case. There may be method to their madness: Since his campaign, Bush has been calling for a "restructuring" of Medicare and Social Security, and his idea of restructuring rests heavily on the private sector.

Bush wants to allow people to divert some of the money they pay to Social Security taxes into "private accounts" invested in the stock market. In the days of the market boom, this didn't seem like a terrible idea -- at the time, remember, betting your retirement on the fortunes of a high-flying firm like Enron was an eminently sensible thing to do. Well, we know how that story ended. Now, after the Wall Street scandals, voters may be more inclined to keep their money in old-fashioned, government-run Social Security. And so, pro-privatization Republicans find themselves with a problem: How do you get people to think that Enron is a better investment than Social Security? The answer is obvious: You make the government's finances worse than Enron's.

Many Republicans do actually believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, that supply-side tax cuts will result in national wealth like we've never seen. And the finances of the entitlement programs would have been shaky even without Bush's help. Still, there's reason to believe the White House wants to make the entitlements seem untenable, completely broken, and irreparable other than through privatization. The White House's 2004 budget, for example, includes a section called "The Real Fiscal Danger," in which the administration argues that while people are right to be concerned about Bush's current deficits, the shortfalls pale in comparison to the long-term financial problems we'll see in Social Security and Medicare. "Whatever judgment one reaches about the deficit of this year or even the next several years combined, these deficits are tiny compared to the far larger built-in deficits that will be generated by structural problems in our largest entitlement programs," the White House says. Translation: If you think this is bad, just wait.

The document concludes by calling for immediate changes in Social Security and Medicare. "We must not delay in enacting reforms to make these programs financially sustainable," it says. "Delay erodes the confidence of today's workers that Social Security and Medicare will be there for them when they retire. And delay increases the financial threat that we leave to our children and grandchildren."

But there are some liberal economists who don't believe Social Security faces any crisis at all, provided politicians have the will to suck it up and pay what they owe. The head of this group is Dean Baker, the co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and the author, with Mark Weisbrot, of "Social Security: The Phony Crisis." Baker thinks that, with a few adjustments, Social Security can remain sound for the long term; he particularly objects to the notion that, come 2018, the Treasury is going to default on all the money it's been borrowing from Social Security. "These are government bonds we're talking about," he says. "You're talking about defaulting on bonds -- and if they do that, why would they default on Social Security bonds first? What about the bonds held by wealthy people? You're saying the government is not going to pay back the money it owes to old people?"

Baker says that Clinton made a strategic mistake when he began talking about "saving Social Security" in 1999. "That was a decision that came out of the focus groups," he says, because Clinton knew that Social Security is an enduringly popular program. But by saying that Social Security needed saving, Clinton was admitting that it was broken. And by admitting that it was broken, he let the Republicans come in with their privatization plans.

He also points to one idea for bolstering the finances of Social Security that could be an alternative to privatization: raising taxes. "I don't doubt at some point we will raise taxes. I'm sure we will," he says. "What is a little bizarre is that a lot of the discussion takes the position that we can't raise taxes, and I don't know what country they're living in."

But who will call for raising taxes? Certainly the Republicans won't, and therein lies the brilliance of their plan. If Bush is reelected, Social Security "reform" could be his main goal for his second term. John, who supports privatization, says, "I was in a meeting where one of the administration people came in directly from talking to the president. And the message from the president was: It's coming. We're going to talk about reform. It's coming soon." The Democrats, at that point, will face a choice. They can give in to Social Security reform. Or they can call for tax increases to "save" the program. Either one is a political victory for Bush.

Baker believes that Bush's package may become law. "After 2004, if they have control of the Congress, there's a better than 50-50 chance we'll see some form of private accounts," he say.

And John, who has been pushing for such a system for many years, is excited at its prospects. "I'm very optimistic, extremely optimistic," he says. "The thing is the alternatives are so much worse. If we do nothing, we see the debt climb."

Shares