In an auditorium on the Chennai campus of the Indian Institute of Technology, Brian Behlendorf is stumping before 200 engineering students. The pony-tailed founder and CTO of the Silicon Valley start-up CollabNet is here, ostensibly, to talk about open-source software. The event has been organized by the Indian Linux Users Group-Chennai; the 30-year-old Behlendorf, who coordinated the growth of the hugely successful Apache Web server project in its early days, is one of the heroes of the open-source movement.

But he's also an executive of an American company that has outsourced a significant part of its operations to India, placing him at the center of the firestorm that has erupted in the United States over the globalization of white-collar jobs. So he can't avoid addressing the issue of what has really brought him to the subcontinent, even as he adds his own unique twist to the debate.

"Outsourcing is a sensitive topic in the U.S. for political reasons," Behlendorf says. "But the open-source community has been doing outsourcing since the beginning." Programs like Apache and Linux and many others, he argues, were developed by thousands of volunteers from around the globe -- an example of massively outsourced labor. In a sense, the move by Western corporations to outsource programming operations to developing nations isn't just about cutting costs, it's about adopting a new software development model.

Behlendorf's audience is receptive to his remarks. It is made up of students from one of India's most elite engineering institutions -- a school that's harder to get into than Harvard, a school so competitive that its tens of thousands of applicants are known as "aspirants." The men, who make up the majority, are dressed in button-down oxfords and belted khakis, the women in flowing salwar kameez. There's only a smattering of geeky T-shirts: "2001 Welcome to Linux: It's now safe to turn on your computer," reads one.

After Behlendorf has finished speaking, the students come up to the podium to pepper him with questions. When he finally leaves the stage, a dozen engineers follow him out into the humid night, intent on spending every possible moment with him until he disappears into the car that will take him back to his $130-a-night room at the Sheraton. Then, the students walk away into the dark, a loose group scattered below a jumbled canopy of banyan, neem, mango, tamarind and eucalyptus trees populated by dangling wild monkeys.

Behlendorf isn't here in Chennai for the second time in 10 months just to spread the open-source gospel. He's here because the boom in offshoring is resulting in a tight labor market -- in India. In the topsy-turvy logic of globalization, it's Behlendorf who's here to court the engineers: highly educated, technical talent that costs a fraction of what it commands in the U.S. Recruiting such talent is becoming an ever more competitive endeavor for companies looking to join the offshore flood.

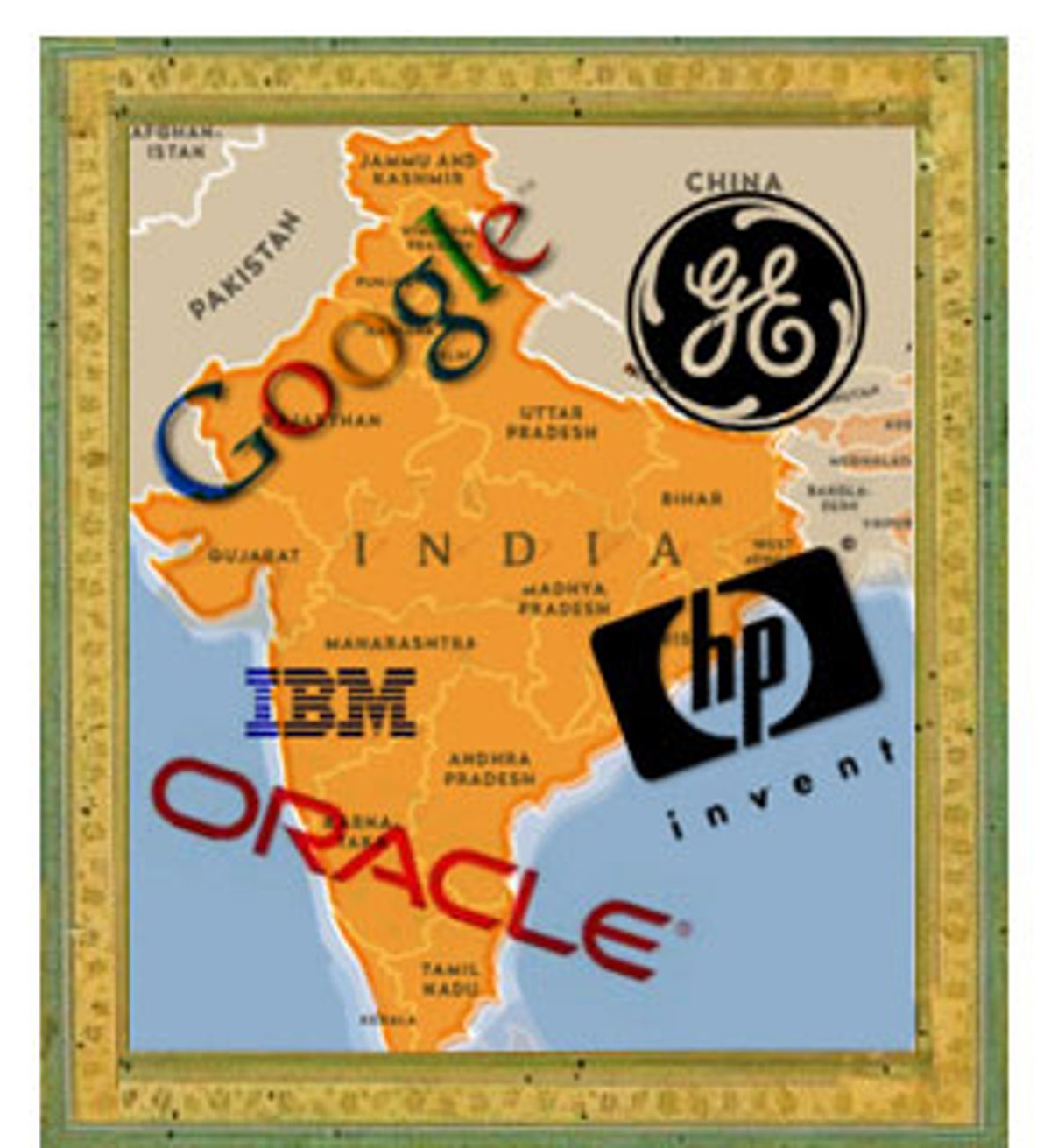

In the U.S., the rush to outsource labor internationally is increasingly being seen by workers as an us-vs.-them zero-sum game. As they watch one corporate behemoth after another -- IBM, GE, Oracle, HP, Google -- send significant portions of their operations offshore, their agitation is burgeoning into a political hot-button issue. According to a new Gallup Poll, 58 percent of Americans say that outsourcing will be "very important" when they decide their votes for president. And 61 percent say that they are concerned that they, a friend or a relative might lose a job because the employer is moving work to a foreign country. Analysts' estimates that 3.3 million jobs are likely to be lost to outsourcing by 2015, and that 14 million are vulnerable to foreign competition, have turned India into the new Japan in the imagination of American workers: an ominous economic threat to their livelihoods. Despite assurances from economists that the furor is so much protectionist alarmism, the nagging question remains: How can you compete with a worker who makes a 10th of your salary?

But for Behlendorf and CollabNet, the outsource-or-not-to-outsource challenge is no cut-and-dried case of greedy American corporations sending jobs overseas. Behlendorf, as befits his open-source roots, is an idealist. Taking a global perspective, he believes that spreading the wealth internationally is good for the world in the long run. He and his fellow executives want CollabNet to be a truly global company, with no distinction made between employees in one country or another. But even more to the point, CollabNet's main product, SourceCast, is a set of software tools that facilitate development among teams of programmers working in different locations.

In other words, CollabNet's developers, both in the U.S. and India, are hard at work writing code that makes it easier for workers on opposite sides of the globe to work together effectively. CollabNet even "eats its own dogfood," as the saying goes, using its main product as the development environment for writing the SourceCast code.

One important market for SourceCast: corporations that outsource.

CollabNet's story is symbolic of a larger truth about the globalization of white-collar jobs -- particularly those in the technology sector. If Silicon Valley now faces an uncertain future as a center for software development, the seeds of that uncertainty were planted not in India or China or the Philippines, but right at home. The build-out of the Internet and the tremendous advances in computer technology over the last decade have opened up new passageways between disparate economic realities. And no one has embraced one of the central premises of the Internet age -- easy interconnection between everybody -- more than software engineers. The immense strength and vitality of the open-source software phenomenon is a clear testament to that.

It wasn't so-called "Benedict Arnold" CEOs or greedy shareholders or even the ruthless laws of economics that crafted these new virtual workplaces where job performance is measured purely by your output on the screen, no matter where you log on from. Technological innovation and investment opened up the doors for coders in India and China and everywhere else. It is one of the tremendous ironies of the digital era that the easy flow of capital and labor to every inch of the globe, made possible by the superhuman efforts of American and European programmers, has ended up wreaking havoc on the job security of those very programmers.

Got a problem with that, Silicon Valley? Don't blame India, and don't blame the CEOs. Blame yourself.

If you pick up a phone in CollabNet's office in Chennai and dial a Brisbane, Calif., extension, you can reach the West Coast via VoIP Internet telephony, no long-distance call required. It's a hotline from one economic reality to another.

In Chennai, day laborers do road construction on the clogged city streets by hand without benefit of bulldozers or cranes, working with pickaxes and shovels at the rate of $4 U.S. a day. The traffic veering around their stooped, sweaty forms is a writhing choke of belching open-air auto-rickshaws, cars, motorcycles and scooters. Barefoot bicyclists brave the squalls, often with red, blue, yellow and green jugs strapped to the back of their bikes: water.

There's such a severe shortage of water here that while the wealthy buy theirs commercially and have it delivered to their homes in trucks by the tankful, their servants -- the legions of drivers and cooks and maids and guards -- wait in line for more than an hour each day to receive their own subsidized rations.

Walking the ragged sidewalks here means dodging not only the other pedestrians and stray dogs, but one-man-band businesses that have annexed scraps of pavement: a tailor sits behind an ancient sewing machine in the middle of the pavement, open for business.

And yet, on the same streets where child beggars wade into traffic, putting their cupped filthy hands to their mouths to plead for food, billboards advertising "Business Process Outsourcing" broadcast an entirely different set of possibilities. Glimpses of it are visible in the dilapidated local airport, where it is 80 degrees Fahrenheit at night with no air conditioning (except for ceiling fans -- which are all turned off), but there's a room of smudged, gray PCs where travelers can check their e-mail. And you can hear it at a charity benefit, where the famed Odissi dancer Sonal Mansingh teases the posh audience with a "Message from Krishna!" jab when their mobile phones persist in interrupting her performance.

Past the street vendor selling vegetables from a wooden cart, and the men in flowing kurtas, an elevator takes you up to CollabNet's offices on the third floor of Trimex Towers on Subbaraya Avenue. Past the guard at the front door, what's shocking is not how different the office here is from the corporate headquarters back in Brisbane overlooking the San Francisco Bay, but how fundamentally similar it is. You're greeted with a setup that could be any start-up in Mountain View or Sunnyvale: rows of cubicles filled with guys in their 20s -- and a few women -- dutifully engrossed in their computer monitors.

There's a sport to picking out the superficial differences between CollabNet's two offices: In Chennai, the bathroom doors are marked "ladies," "gents" and "executive." In Brisbane, the receptionist wears a trendy pink Paul Frank T-shirt with a signature monkey cartoon on the front over jeans with a rainbow-colored stripe up the side. In Chennai, the receptionist sports an elegant salwar kameez with a flowing dupatta scarf draped down the back -- casual wear by local standards.

In Brisbane, the lunchroom is stocked with a Galaga arcade game, a foosball table, a serve-yourself fridge full of soft drinks and a pantry bursting with granola bars. In Chennai, a servant delivers sweet south Indian coffee and cookies, and workers take coffee and tea breaks both morning and afternoon.

But the deeper into the work environment you get, the more the two offices appear identical at the most critical level: the technology. On their desktops, the developers and Q.A. (quality assurance) engineers here use the same tools as do the coders in Brisbane. Call it virtual, if you must, but in a very real sense, they are working in the same environment.

The real CollabNet workplace is not in Brisbane or Chennai, it's in the packets of information zipping across the Net, whether via instant messaging software or e-mail or through the features of the SourceCast collaboration software. All that really matters is who is online at any given time. In this Web-based development environment, notification is by e-mail, the browser is the interface and deploying means giving someone else a URL.

There are advantages to such virtuality, says Behlendorf. "Instead of having a conversation in person, you have the development over e-mail. If you have a conversation in person, you're lucky if someone takes notes. On an e-mail forum that stuff is always recorded. It's always available for searching."

Add a lot of cheap bandwidth to the mix and anything is possible. "During the [dot-com] boom a lot of telcos were laying a lot of cable across international lines. The cost of getting a T1 or a T3 to the other side of the world is no longer prohibitive for most companies," says Behlendorf. "There's actually a glut."

Now, someone is always working at CollabNet. "Any time of the day or night, 24/7, 365 days a year, people are on our IRC [chat] channels," brags Chris Clarke, 34, a director of engineering, who works out of Brisbane.

CollabNet is unusual in the outsourcing/offshoring debate in that the product it is selling is explicitly aimed at aiding the work of collaborating programmers. But the merging of offices across time zones and international borders is, on a global scale, a consequence of the advances in computer and telecommunications technology. Outsourcing, viewed from the technological perspective, is not surprising, nor is it necessarily exploitative. It's just what happens when you connect the world together.

CollabNet's arrangement between its U.S. and India offices is not technically outsourcing, in the sense of a particular company task being contracted out to another company. Everyone in the Chennai and Brisbane offices is a CollabNet employee. On the company's intranet, the directory shows the names and faces of employees in Chennai, India; Brisbane, Calif.; and Chicago, Ill., intermingled in an alphabetical index of who works here -- wherever "here" is.

CollabNet has brought its offshore workers into the company, which in an unfortunate parlance of the Indian software industry is known as running a "captive" facility. There are no third-party buffers separating the workers in Chennai from the employees back in Brisbane, aside from the fact that they are paid on scales that are orders of magnitude different.

CollabNet even put the programmers in its offshore facility to work on its core business: writing the SourceCast software. While Q.A. testing is mostly located in the Chennai office, development work now occurs both in the U.S and in India. Programmers in both places not only work on the same projects, they literally modify the same files of code.

How did CollabNet get here? The reasons are a mix of pragmatism and idealism. In late 2002, the business environment for a small technology company looking to expand was brutal. CollabNet had been through layoffs but, paradoxically, what the company really needed was more people -- a lot more people.

"We just needed more arms and legs to be able to provide the robustness that the product needed to have," says CEO Bill Portelli.

"What we were capable of doing with the people on staff was not what we needed to win business," says Behlendorf.

In fall 2002, Portelli says, he was receiving three solicitations a month from outsourcing companies, up from a rate of about one every other month just a year before. E-mails and follow-up phone calls poured in: "We'll help you do this, cheaper, smarter, faster!" (Now, he gets about a dozen such offers a month.)

But the more the company explored these outsourcing options, the less it wanted to pursue them. Behlendorf objected to what he dubs the "fast food" model of services outsourcing: writing a specification, sending it to another company with developers offshore, and waiting weeks for the code to come back. Would this result in software the company wanted? As a pioneer and veteran of the inclusive, open-source world, Behlendorf just found the idea distasteful.

"I wanted a team there that felt like they were CollabNet," he says.

Jack Repenning, 51, a senior software engineer in the Brisbane office, puts the power dynamics of the traditional outsourcing relationship in stark terms: "Enterprise offshoring is a kind of colonialism, like growing pineapples in the Philippines or bananas in Hawaii. It's very demeaning and counterproductive: Do this and shut up."

CollabNet wanted to seed collaboration among all its developers, as opposed to creating a two-tiered model of service provider and client. It's a model taken directly from the open-source world. "This year, you'll call it outsourcing, but in a few years, you'll call it global development, where there are locations everywhere," says Jason Robbins, a developer who was the 10th employee at CollabNet when he worked for the company remotely from Southern California. "And you won't think of breaking off a chunk of development with limited risks and management responsibilities for another second-class team to do. Instead, development organizations will think of it as a global employee pool," says Robbins, now a lecturer at the University of California at Irvine.

This was the model that CollabNet was preaching to its customers and prospects: If they couldn't make it work themselves, did they have any business selling it?

There was another, even more pragmatic reason to avoid the subcontracting-out style of outsourcing. Despite a reputation as a low-cost alternative, outsourcing services still come at a premium, since you're paying a middleman to hire and manage the remote office of cheaper labor. If you can pull it off yourself, in the long run, it's even less expensive to run your own shop.

So, instead of hiring the work out, CollabNet decided to merge with an existing software company, Enlite Networks. Enlite was incorporated in Delaware, with management in Mountain View, Calif., and a few key developers in Plano, Texas. But by far the majority of its coders, some 31 programmers, were in Chennai. From its inception in 1999 Enlite was organized around the assumption that work would flow back and forth between the U.S. and India.

The company product -- a project management tool -- was folded into SourceCast. "They were not doing low-level work out there," says Behlendorf. "They were doing J2EE, heavy database stuff, the same kinds of things that you have people doing out here."

In early January 2003, when the company told the developers in Brisbane about the acquisition, the fallout was immediate and predictable. "A lot of people thought most of the engineering staff was going to lose their jobs," says Dan Rall, 26, a senior software engineer.

At an engineering offsite in the Marin Headlands, soon after the announcement, a "V.C.-type" speaker came in to put the company's move into a larger economic context, developer Leonard Richardson, 24, remembers.

"He talked about how the agricultural economy had become the industrial economy, which in turn had become the knowledge economy. Someone asked him what comes next, after outsourcing takes its toll on the knowledge economy. He said that if anyone had any ideas he was interested in hearing them," says Richardson.

Kevin Maples, another programmer, dubbed this vague notion the "I don't know, you think of something" economy.

The developers in Brisbane weren't the only ones who were worried. The Enlite engineering team in Chennai was also apprehensive. Here they'd been developing their own product, explains Muthu Krishnan, one of Enlite's U.S.-based founders. What exactly would they be doing for this CollabNet company? And what would these American executives in California expect of them? Programmers who had been writing code were put on the relatively less interesting task of testing software for bugs.

CollabNet had almost no QA department back in Brisbane, and this was an easy way to get an immediate benefit from the merger: The engineers in India would find bugs while the U.S. developers slept. Plus, it would help the engineers in India get up to speed on the product. Still, going from writing code to testing can only feel like a demotion.

The story of how CollabNet has striven to integrate its Indian and American engineers offers an illuminating test case in the evolving drama of globalization and its impact on the world's labor force. Along with the usual merger upheavals, the company had to surmount the perpetual barrier of a 13-and-a-half-hour time difference, and vast cultural differences as well. And no matter how enlightened the management, there's no getting around the economic facts. Indian programmers cost less; therefore it makes economic sense to hire them. Even for the most highly valued programmers in Brisbane who support what their company is attempting to do, that equation still chafes.

The 40 some-odd programmers, quality-assurance engineers and customer support staffers who work in CollabNet's two-floor outpost in Chennai are mostly in their mid-20s. By mid-2004, the managers here hope to recruit about 15 more of them. The market for their skills has become so heated in Chennai that headhunters brazenly call them up in their cubicles to solicit their services, dangling pay hikes of 30 percent.

"A programmer with two or three years of experience gets a salary of more than a big government official who had to struggle to get to that level," explains P.V. Gopinath, 41, a development manager. And Chennai, a southern port city formerly known as Madras, is sleepy compared to Bangalore, with considerably less job-hopping and salary inflation; it's an Austin, Texas, to Bangalore's Silicon Valley.

For these programmers, a job working for an American company like CollabNet is a ticket to the good life -- and a lot of long hours. When 29-year-old Venkat, an engineer who once worked Q.A. but now fixes the bugs he found as a tester, first started working with the CollabNet developers in Brisbane, he would work from 2 p.m. to midnight, so he'd have more time to chat with his remote colleagues in the chat rooms. But despite the late nights, he says, "I.T. [information technology] improves your lifestyle. You make more money. You have more satisfaction." But he adds, "You don't get a lot of holidays to go around and enjoy it."

Ramaswamy Subbaroyan, 34, a senior software developer who worked for 18 months in Boston for another company on an H1B visa, says that the rise of the I.T. industry in India has "put a lot of money in middle-class people's pockets." And the lifestyle that an I.T. job in India brings beats the ones back in the States. "Once you reach the middle level with 10 to 12 years experience, life is pretty good here, compared to people in the U.S. with 10 to 12 years experience."

But, he says humbly, the developers in the U.S. are superior: "The best programmers are still in the U.S. It's more of a do-it-yourself, self-starter culture." But he sees that changing in India, where a government job used to seem attractive because of the decades of job security it could offer. "Young people are cutting loose," he says. "They're not bothered by job security."

The same is not true for American programmers.

Since the merger, the programmers in Brisbane have not been axed en masse, as some had feared, but in the last year there have been some layoffs of individuals. And some developers have gone from coding almost all the time into very different roles; they've been put to the task of training and mentoring the staff in India. "You have to be a people leader, and not just sit in your small cube working on stuff," says Muthu Krishnan, one of Enlite's original U.S.-based founders. It's a real-life version of the advice that venture capitalists and economists have for American programmers who are concerned about their own prospects: Move up the food chain.

That means more documentation and lots of late-night sessions answering questions on chat. One insomniac Bay Area developer who happened to be online a lot was on the receiving end of so many of these queries that he started getting small tokens of thanks in the mail from his colleagues in India. One present was a small plaque with a formal declaration of friendship.

But moving from writing code to encouraging and managing a team of coders remotely is not for everyone. "I was a technical lead, but I didn't want to lead a team remotely. I didn't want to stay up all night bringing people along," says Michael Stack, who quit to work at another software company. "I remember interviewing someone long-distance over the phone, and just thinking. 'This doesn't work.' Interviewing is one of the most important things you do in a company. Trying to get a reading off of somebody off a bad phone line, I was at a loss."

"Their jobs changed or are changing," says Sandhya Klute, a director of engineering in Brisbane. Although she was hired eight months ago, well after the merger, Klute found herself still trying to reassure the 22 engineers here that they wouldn't be irrelevant as soon as the developers over in India got up to speed on the product.

Klute, who worked for Hewlett-Packard for 21 years as a middle manager, argued: Why would the company hire a new manager in Brisbane if they were just going to get canned? But she also struck a tough-love note: "The reality is we don't have to like it. Just look outside, it's happening in every other company."

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of the merger has been ironing out workplace culture issues. In Chennai, programmers call their managers "sir," and lofty job titles command respect. A tester wouldn't feel comfortable disagreeing with the CTO or a V.P. But in Brisbane, programmers treat each other as peers and respect is accorded based on contribution -- a style that comes directly out of the open-source world of software development.

So it's hard for a 26-year-old technical lead in Brisbane to understand why a programmer in Chennai might be too intimidated by him or just too shy to ask a lot of questions that could speed the training process along. "They can't just pop on over to my desk and ask me a question," says Dan Rall, 26, a senior software engineer. "But if they could, would they?"

No wonder that when Behlendorf spoke to those IIT students in Chennai his biggest piece of advice to them was to not be shy about participating. "I understand there are big cultural differences," Behlendorf told them. "The culture here is a lot more polite," but it's by jumping into the sometimes-bruising online fray that you can contribute and build your reputation.

"We don't get as much work out of them as we wish we did," says Repenning. Is the culprit the cultural mismatch? Are the American developers still not communicating clearly enough? Do they need to write more documentation? Is it the stupid time zone problem? Or do the developers there just need more time to ramp up? Or some combination? Repenning is not sure.

"You find yourself spending about equal time worrying about them moving up the value chain to take your job, and wishing that they would move up the value chain faster so they could do their jobs," says Repenning, who now leads a team of four engineers in Chicago and two in Chennai.

On the American side, the tension of working in a shrinking job market can make the cross-cultural interactions uneasy.

"This industry is having a hard time. Friends are losing jobs. Sitting beside someone who makes a 10th of what you do, it's a pressure you feel," says Stack, the American developer who left CollabNet to work for another company. "On the surface, all goes along swimmingly, but there is an underside not being discussed. That colors your interaction no matter how you might dismiss it."

Rall, a tech lead, is obviously proud of how fast some of his team's Indian engineers have adapted to their new roles at CollabNet -- such as Venkat, whom he dubs "a total star." And he says that some of the fears of job loss in Brisbane have abated over time. But he still wonders what the company's new deal means to American engineers just a little younger than he is, who are just getting out of school:

"A 21-year-old who just got out of school here with $100,000 in debt, what did he get for that debt? What does he have to look forward to now?" says Rall. "We don't hire those people anymore. We only hire senior engineers." He's not the only one wondering, since in the U.S. the the number of unemployed college graduates has recently surpassed the number of unemployed high-school dropouts.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

It's morning in the CollabNet office in Chennai, and Behlendorf has just come in after staying up until 4 a.m. in his hotel room at the Sheraton answering the flood of e-mail from California that arrives after dinner in India, when it's 9 a.m. back in Brisbane. This is his second visit to Chennai in the past 10 months, and he thinks he's already seeing signs of change in the streets. There's less litter. Road conditions seem to be improving -- at least there's a lot of construction on them. He's optimistic that the influx of Western capital is playing a role in helping improve things here.

In the early 1990s, Behlendorf was the founder of SF Raves, the San Francisco mailing list that launched countless all-night underground parties in the name of "community." He still deejays until dawn. Is this the man American workers are thinking of when they rail against "Benedict Arnold executives" sending "our jobs" overseas?

Behlendorf says that CollabNet could have hired 10 people back in San Francisco for what the India office costs them: That's a ratio of about 4 to 1. But he thinks that wouldn't have been enough people to make the company's product succeed.

"We saved the jobs of the people who are employed in San Francisco by hiring people here [in India]," he says. "I don't know that we would be around as a company if we hadn't done that. What was the right thing to do, morally?"

Shares