More than seven years ago, Ric Hunt, a wandering computer jock from Iowa, proposed to an astonished Pedro Gómez, the principal of Yelapa's telesecundaria school (for kids in seventh to ninth grades) that they start a computer lab in the jungle. At that time Yelapa, an indigenous community down the Bay of Banderas coast from Puerto Vallarta, had no grid-based electricity; Gómez was still struggling with the satellite technology that brought lessons to the school daily from Mexico City.

But the Honda-powered satellite was precisely the point for Hunt; he had somehow stranded himself in one of the few places on earth where he couldn't plug in easily. That was important to him, since he wanted to become a registered Microsoft technician and travel through Central America wiring up hotels. He needed to use a computer to study for the Microsoft exams, and his elegant solution to this problem was to invent the jungle computer school in exchange for the right to use A.C. power at the telesecundaria.

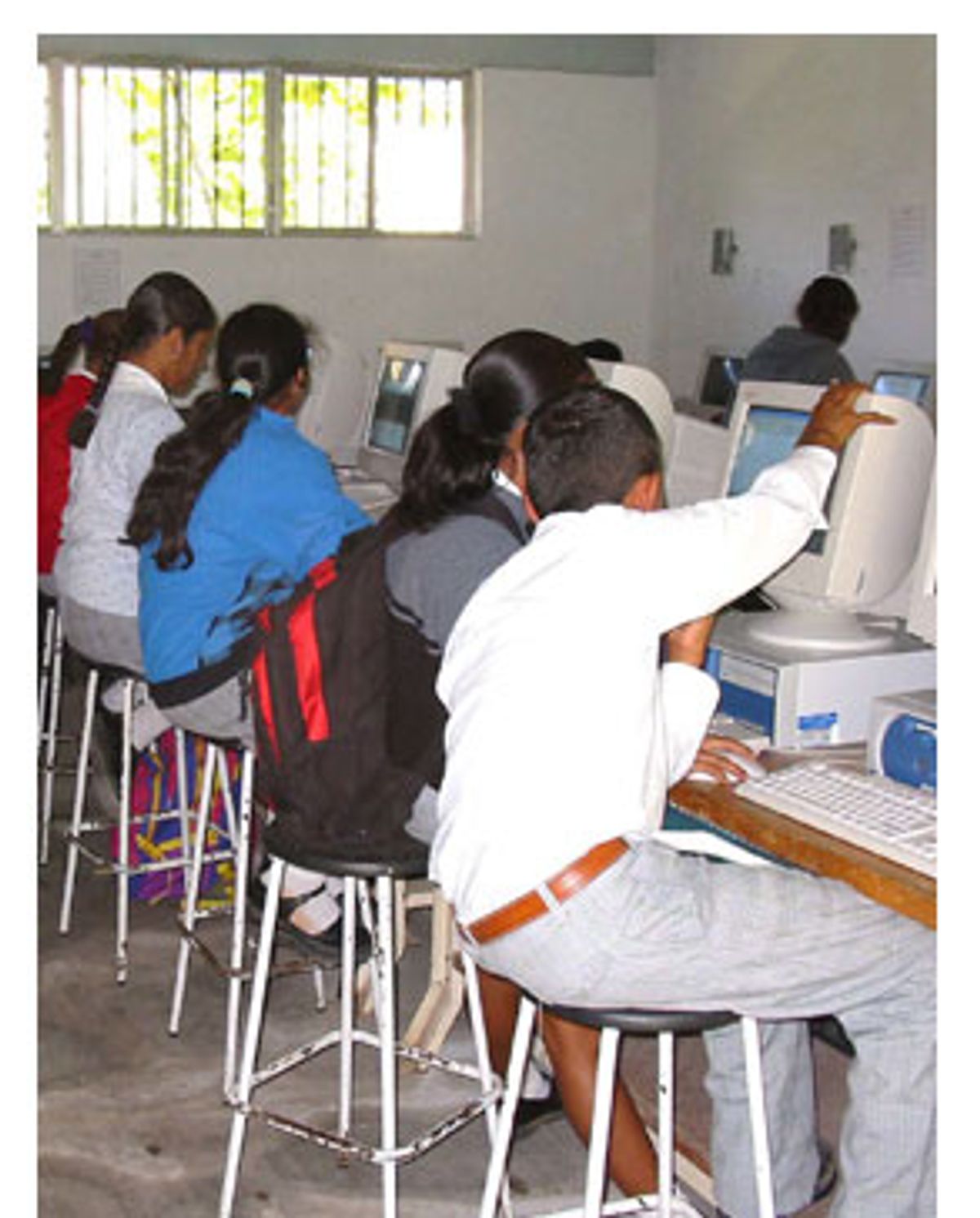

The story of how the jungle computer school has struggled into existence, despite the differing motives and understanding of its founders, provides some perspective on how the technological frontier advances -- by chance as much as design. From its almost accidental beginning, a computer school has taken root, with a dozen Pentium 5 machines, some of them networked to a printer, and classes not only for the secondary school kids but also for students in the new preparatorio (the equivalent of high school), which shares the space.

Hunt jump-started the school with a donation of two old computers, one with an AMD 586 processor and the other with an Intel 386, plus a scanner and a laser printer. Just getting this hardware to Yelapa was a logistical triumph, since there were no roads to the place and everything had to come in by boat. But he and Gómez quickly ran into difficulty with each other, partly because of the language barrier, partly because the school considered Hunt's Microsoft activities to be using too much generator time when gas was getting expensive, and partly because Hunt's plans, which included a satellite network connecting all the schools in the district, were far too grand for Yelapa's simple needs and Gómez didn't understand them. The teacher was totally baffled, for instance, when Hunt showed him how he had gotten the machines to boot in any one of three operating systems -- DOS, Windows 95, or Unix. Gómez had only a vague idea of what any operating system did. (A map of the satellite network, which Hunt is still promoting, may be found on his Web site.

I met Hunt in 1998 and took part in many meetings between him and Gómez. With other North American residents, I helped translate for the computer school, structure a program, write proposals, and make contacts, all the while suspecting, as most of us did, that Hunt could never pull it off. What he proposed to do was technically feasible, but it was far beyond the Yelapa kids' needs or the school's ability to manage.

Yelapa has electricity now, and eventually, says Gómez, the school would have thought about computers. It eventually got equipment for its current lab through the Jalisco Department of Education and COBAEJ, a public organization that helps direct state funds for education, as well as software from Microsoft (partly due to Hunt's efforts). But, Gómez adds, "This [the computer lab] is the future of Yelapa. And Ric got it going."

By doing so he helped give the town a toehold on the network frontier. With local resources now accessible from anywhere in the world, the environment here is essentially defenseless. Local agencies have to meet pressures that result from decisions they have no control over and that they have few resources to counter. Considering the changes wrought by what he sees as a new social form, the "network society," sociologist Manuel Castells suggests that the old '60s slogan has to be flipped over; people must think locally and act globally. "If you don't act globally in a system in which the powers are global, you make no difference in the power system," Castells says.

It is hard to see how a hamlet like Yelapa can have much of a global impact, though it is already acting globally through the various Web sites that advertise tourist residences in town. None of these, however, are run by Yelapans. In time, the computer school will generate a cadre of local youths who understand something of global technology. COBAEJ requires schools to maintain a strict curriculum, with classes in computer science as well as math, chemistry, physics and English. Students in the prepa are getting instructions in theoretical "informatics" from Alex Urrutia, a Yelapa native who left town at an early age and wound up as a Microsoft techie in Montreal before returning to the village on a self-generated sabbatical two years ago. The secondary school kids are learning Word and Excel, and looking things up in Encarta, just as Microsoft had hoped.

There is still no Internet connection. Urrutia wants to teach a second-year class on the needs of businesses and the use of the Internet, but can't go online. The original appropriation to get the prepa going included Internet money, he says, but Gómez vetoed it, partly because he wanted to spend the funds elsewhere. Yelapa is so remote that it had never had a high school before; it could not justify spending the money on importing teachers to live there. (The telesecundaria gets its lessons by satellite for the same reason.) The first two years of prepa operation have been carried out with pickup teaching staffs; last month, in fact, the school lost its English teacher, a North American, when he abruptly left town with no notice.

There will be plenty of time for the Internet, Gómez told me, when the students have a firmer grasp of the basics and when the school's enrollment reaches three full classes. (It started with only a sophomore class, adding a junior class this year as the first students advanced; only next year will there be a full complement.) Nevertheless, the indefatigable Hunt, who now lives in Mexico City, has scared up a small private donation to cover initial ISP costs and is working with UNETE, a business group that supports public schools, to provide more equipment and network connections. Meanwhile Urrutia says that some of his students e-mail him from their homes. Some Yelapa families have computers, and there is one locally run cybercafe, a single machine in a local restaurant, Mimi's.

Mimi herself is part of another movement to bring Yelapa's young people into the mainstream; she is on the all-Yelapan board of a project to start a youth center in town that will offer art, music, dance, martial arts and computer classes for kids, using both local and expatriate talent for instruction. Before opening its doors, the school received donations of four laptops and promises of five more desktop computers this year. The center grew out of a bequest from a longtime American resident, Sam Harrison, who died in Yelapa and left $5,000 to be spent for the benefit of the local youth.

Aware that their $5,000 would melt very quickly, the project leaders went looking for official backing, an effort that succeeded beyond anyone's expectations; the youth center dovetailed neatly with the plans of the Mexican government for the development of Yelapa. The municipio of Cabo Corrientes, of which Yelapa is a part, wants to create a cultural center in the town. On receiving a presentation about the youth project, the municipio promptly made its board the lead agency for formation of the cultural center, with the municipio's ecology officer, Yelapa resident Luis Enrique Morales, as liaison. (It bothered no one that these goals and responsibilities are significantly out of sync; everyone in Yelapa expects to multitask.)

The presence of Morales, the establishment of a municipio office in Yelapa, the appearance of actual police here, plus Yelapa's increasing Internet presence, all attest to the new influence of the outside world on the town. Whether it has the political skill, and influence, to keep local control is questionable. The community leaders are well aware of the effects of development on other Mexican locales that have become tourist centers. Their control of the land and their traditional political autonomy, as part of an indigenous community, give the locals some protection. Nevertheless, Yelapa politicians have frequently been bought in the past, and the land has become very valuable. In addition, the indigenous Chacala community that Yelapa belongs to is in debt to the federal government for unpaid taxes on the land it leases to tourist developers. Urrutia thinks that the combination of fiscal mismanagement and rising crime and drug problems may create a wedge for outsiders to gain control of community land.

As this issue is being decided, Yelapa's people will go on wiring up as fast as they can, and more tourists will be attracted to it from all over the globe. Already, its new commercial villas promise all the comforts of home, rather than jungle romance in a thatched hut. It is hard to say what the impact of the first neon sign will be. Given Yelapa's small size and skimpy economy, the coming of electricity and digital technology may cause very fast growth and make it a frontier boomtown. At the same time, projects like the computer school and the youth center, and the town's new political sophistication in dealing with Mexican governments, rather than relying on its weakening protection as an indigenous community, offer Yelapa some way of interacting with the network that has annexed it to the global economy.

Shares