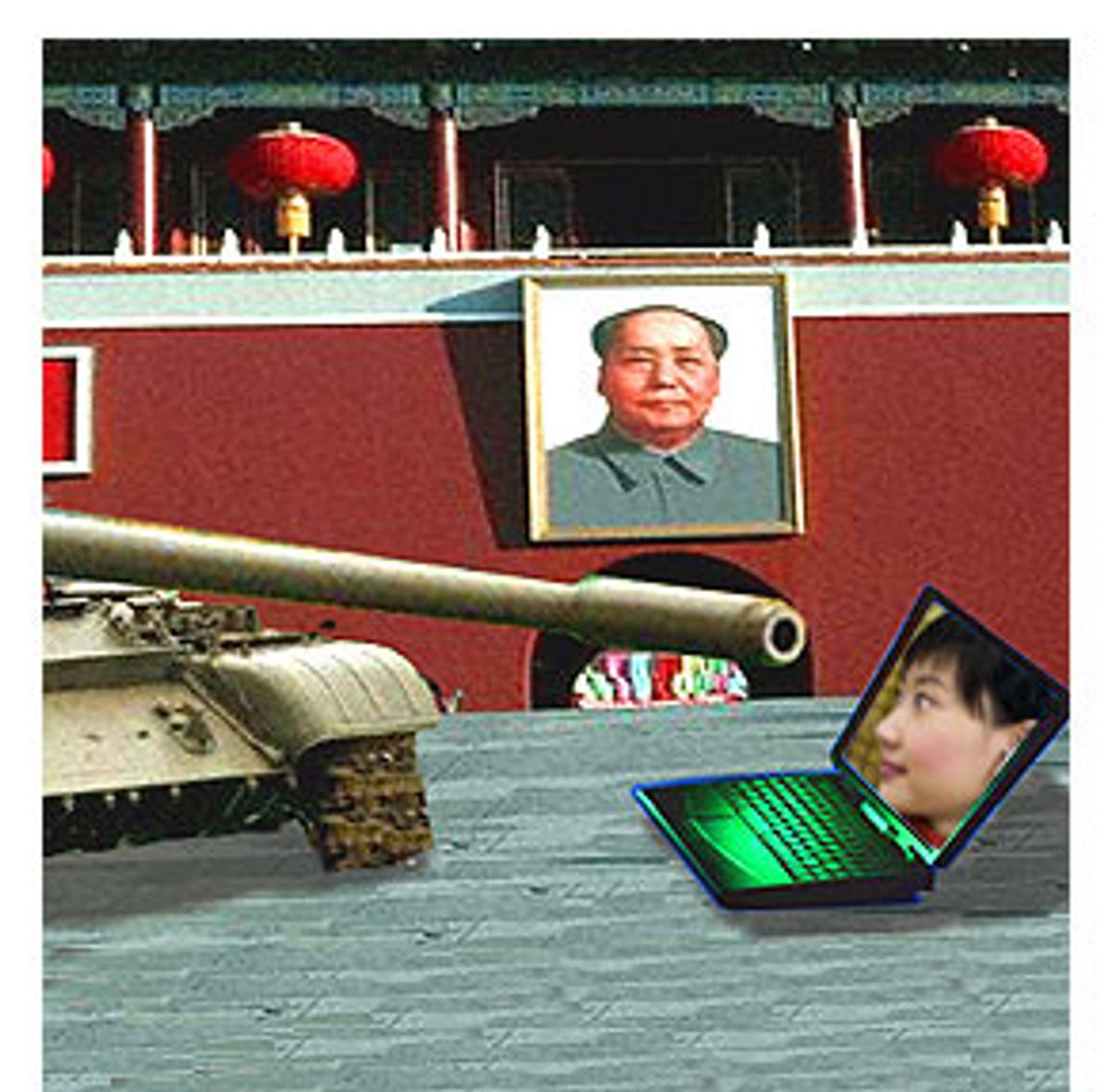

Fifteen years ago today, a solitary protestor stood in front of a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square, and faced them down. In doing so, "The Unknown Rebel" became a worldwide symbol of the power of the individual. Over the last decade and a half, as we in the West have watched that video clip again and again, it's easy to forget what the real outcome of the showdown on Tiananmen Square was: hundreds of protesters were killed in the streets, while thousands more were wounded.

Today, the People's Republic of China often appears to be a kinder and gentler nation. Nowhere is this seemingly more evident than on the Internet. When China opened to the door to the Internet a decade ago, the move was widely seen as a huge step towards promoting free speech within the People's Republic. Despite near-constant government monitoring and filtering, China exhibited profoundly more openness than other totalitarian regimes, such as in neighboring Burma where Internet access is still off-limits to the common people, and military intelligence reads each and every e-mail message that crosses the border.

Internet usage, meanwhile, continues to surge in China. Government statistics cite 80 million regular Internet users as of December 2003, up 20 million from the year before. Most of these people go online at Internet cafes; there are some 110,000 of them in the PRC. This explains how China can have 80 million users, with only 40 million computers. Yet old habits die hard.

Last fall, the government announced that it was implementing an "Internet cafe technology management system" to cover the entire nation by 2005. It's already up and running in a few provinces. Amnesty International reports that 2003 saw a 60 percent increase in the number of people detained or sentenced for Internet-related offences. So far, 2004 has been a busy year as well.

On March 19, Chinese dissident Ma Yalian was sentenced to 18 months in a "Re-education Through Labor" camp for posting an article to two Chinese web sites reporting police harassment and abuse of several Chinese petitioners. Over March and April, Xinhua, the Chinese state news agency, reported that the government shut down 8,600 "illegal" Internet cafes. In late May, the government announced that it would begin screening all online and mobile phone games in order to protect the morality of the country's youth. Reporters Without Borders described the May trial of Chinese dissident Du Daobin, who was arrested for posting pro-democracy articles to the Internet, as "shocking," noting that he was denied access to his attorney and forced to plead guilty.

Blogs weren't immune from the censor's stamp. On March 11, the government shut down Blogbus.com for allowing politically sensitive content to be posted. Three days later, China's other two leading blogging sites, Blogcn.com and Blogdriver.com were also temporarily shut down. As the month went on, the "Celestial Nanny" would also block access to blogs hosted on Typepad.

What kind of effect did this have on Chinese bloggers? As Wang Jianshao, a Chinese blogger who works for Microsoft in Shanghai, put it at the time, "To be safe, I don't want to make any comment on this. It is the hard time for everyone involved in the China blogging world."

But just what is the China blogging world? And where did it come from?

Typical of Chinese bloggers -- of bloggers everywhere, really -- is Wu Chen, or "Dora," a 19-year-old college student in Hangzhou, China, studying management and business. She began blogging a year ago, after learning about it from an American teacher. Her posts -- about her bicycle being stolen, or being upset to discover another girl in her class is wearing the same new shirt -- are politically neutral, and tend to focus instead on her personal day-to-day life.

"It gives readers a window into my life, thoughts, feelings and experiences," said Dora via e-mail. "Visitors exchange ideas. It increases an understanding between people from different cultures across the world."

Of the English-language blogs Salon surveyed -- and there are quite a few -- most avoided politics. A lot of these, like Dora, are students practicing their English. Others have a chatty LiveJournal meets Hello Kitty feel. Xiao Qiang, director of the China Internet Project at the University of California at Berkeley and recipient of a MacArthur fellowship for his human rights work, attributes some of this reticence to an interest the Chinese digital class has, consciously or not, in preserving the status quo.

"You also have to watch who are the people using the Internet," says Xiao, "the demography. It's not just average Chinese people. It's still a very particular kind, usually young, anywhere from teenagers to early 20s. Hardly anyone over 35. They are usually probably being wild in China, whether working at a good job or in college, and have a lot of opportunities. They are not the ones who suffer. They are not the poor workers, they are not the overtaxed peasants. They are not revolutionary. They are not the ones advocating the overthrow of the government. The government is counting on that; the Internet users are their power base. And I think they are basically right."

Higher up the food chain from the lifestyle blogs is Mao Xianghui, or Isaac Mao, a software architect currently involved in bringing the Creative Commons licensing scheme to the People's Republic. Mao is like a Chinese Dave Winer or Jason Kottke in terms of the influence he has had on other bloggers. He was an early adopter and his personal site, which covered a variety of topics, gained a steady following. In 2002, Mao founded a community blog at CNblog.org, inviting others from all over the country and world to join him. The site was called "Blog on Blog," a place for bloggers to get together and post about, you guessed it, blogging.

The bloggers at CNBlog tended to be a highly tech-savvy 20- and 30-something set who promoted blogging as a business tool. Meanwhile, homegrown blogging services began to take off, allowing users to post in Chinese. All of this took place under the radar of the Chinese government's censors.

China had long kept a censorious eye on personal Web sites -- Geocities, for example, was hemmed in years ago. Yet when blogs began to appear, the government did not recognize them for what they were, due largely, says Xiao, to the discretion of those early adopters who played down blogging's potential as a free speech engine.

"They come from an angle where they are negotiating space," says Xiao. "'Let's not promote this thing as an independent media. Let's promote it as a new tool for information management.' Not that they don't know. They did that not because they didn't see it; it was precisely because of the political angle."

"Bloggers have to pay attention to their content," stressed Mao via e-mail. "Try to avoid confliction with government's intangible regulations." Mao says that although he does not shy away from any subjects, "however, I will try to avoid sensitive words."

Still, at the end of 2002, there were only a relative handful of bloggers, perhaps a few thousand. Today, estimates put the number of bloggers in the PRC at anywhere from 100,000 to half a million. Mao thinks there are about 350,000, based on research a team of his is doing on the Chinese blogosphere.

What happened? Sex.

Last June, a 25 year-old journalist named Li Li posted a story to her blog, written under the nom de guerre Mu Zimei, about a tryst she had with a famous Chinese rock star. She followed up with tales of numerous one-night stands and sexual encounters, shocking a country not accustomed to talking about such things openly.

Li Li did for blogs in China what Janet Jackson did for nipple shields in the United States. And like Jackson, she outraged and titillated an entire nation. Sina.com, the largest Chinese Internet portal, posted her stories online, and a full third of China's then-Internet population -- some 20 million users -- logged on to read them. By November, Chinese censors moved to ban both her site and her book. But by that point, the whole country was talking about blogs, and scores of young, tech-savvy Internet users began to set up sites of their own.

Blogging's growth in China is also directly, and somewhat paradoxically, related to the efforts of government censors. In January 2003, the government walled off access to the Blogspot.com domain, leaving Chinese with the ability to post, but unable to share that content with their compatriots, or even view it themselves. At the time, China Internet watchers speculated the entire domain might have been blocked merely to cut off one particular Blogspot site, Dynaweb, which posted lists of proxy servers that allowed Chinese citizens to circumvent the government's Great Firewall.

Not everyone, however, thinks the blocks were purely politically motivated. Pennsylvania native Adam Morris, an ESL teacher working at a British international school in Tianjen, China, keeps a blog at brainysmurf.org, and frequently writes about political issues. Morris speculates that the government blocked access to American blogging services in order to drive traffic to Chinese-owned ones.

"I'm fairly convinced it was a business decision to limit the field of competition for online services," said Morris via e-mail. "The government does this fairly often. For example, when a mainland director comes out with a movie, China bans foreign movies for a month in hopes of driving up sales."

Either way, this silencing had a secondary consequence, according to Xiao.

"My speculation was that I wondered if they really hated Blogger.com, or if it was because of [just] one of those blogs, and in their usual blunt way they blocked the whole IP and didn't care. Those few bloggers had to go somewhere else and they helped start blogging in China."

Nonetheless, the IP censoring remains a tremendous barrier between Chinese Internet users and free and open speech. Roughly 30,000 Chinese are employed maintaining China's Internet monitoring and blocking services, according to Reporters Without Borders. Numerous Chinese Internet users I spoke with complained of the unpredictable ways in which those censors operate. A single comment on a bulletin board system (BBS) might cause censors to pull down the whole board. Thus even those who play by the rules can still find their site blocked by the Chinese government, based on comments someone else might make on the same domain.

To use an analogy, imagine the Bush administration blocking every site hosted on Blogspot.com, due to comments made by a single user such as Atrios. In addition to just walling off Atrios' political site, thousands of other politically neutral, or even supportive, sites hosted on the Blogspot.com domain would be taken out as well.

"[There is] no good blogging service", in China, says Wang. "Blogcn.com and other blogger service providers [are] not stable -- mainly because it has to shut down the server when the government finds any sensitive information on any of the 100,000 blogging users' pages."

And even if you don't have to worry about your site going down, the Great Firewall -- China's attempt to control Internet access -- still has a stifling effect.

"The biggest obstacle in blogging in the PRC is the amount of Web sites that are blocked," said Morris. "For a blogger like myself who writes about current events, this is equivalent to trying to type with no fingers, for we rely on information from outside sources and when about half of the rest of the blog population is blocked, it just makes it that much harder to collect the information. It also makes it harder for every blogger to engage in communities. There are workarounds that allow us to bypass the block, of course, but the simplest solution (via Web-based proxies) is far from 100 percent reliable."

This censorship chiefly affects news portals and blog service providers, who are held responsible for the content posted to their sites and are often ordered to remove material that runs counter to the government line.

"We do have many pressures from the government," said Liang Lu, CEO of Blogdriver.com, at a Berkeley conference on China's digital future. "If your blogger is [posting messages] against the government, the government will call you and tell you to delete it."

Haibo Lu, news editor with Chinese portal Sohu.com, put the process bluntly: "No negotiating, no bargaining, simply remove this news from the front page where you cannot see and the common people cannot see."

"But," points out Liang, "so many bloggers post their own opinion, that within a few days information becomes distributed everywhere. Everyone will know it."

This distribution, however, more often takes place on cellphones via SMS, in chat rooms, and on bulletin boards -- places that offer greater levels of anonymity or impermanence. Dissent more often shows its face in these forums that are harder for the government to monitor and control.

"On the blog more or less your personality shows," says Xiao "You put yourself out there and for both social and political reasons people don't want to be that out there and be in trouble. You're asking for it."

Yet many Chinese bloggers are putting themselves out there, to varying degrees. Among them is Wang Jianshao, who shies away from overt criticism of the government but treads the line rather closely. Wang wrote extensively about the SARS outbreak last year, and has repeatedly reported on site blockages, as well as some of the red tape site operators face in publishing their work. Earlier this year, Wang even went so far as to proclaim, in reaction to the Blogbus block, "I am not a good citizen and didn't follow the current law well enough."

Typically some of the most pointed criticism comes from Westerners like Morris, or the tabloidy Shanghai Eye, a site published out of China, via a U.K. domain, that openly mocks such topics as "Chinese Democracy in Action."

"Practically speaking, we aren't monitored the same way natives are," says Morris. "For Chinese-language bloggers, on the other hand -- although I don't think it's mostly 'killing a few flies to scare the monkey' -- they really have to worry about calling unwanted attention to themselves and their families. Once a Chinese national writing in English was stunned that she heard about the shooting of President Chen Shuibian through my blog and not through official channels (there was a few-day news blackout). She said she wanted to write her feelings but didn't because she was worried about the repercussions. The most Western bloggers in the PRC have to worry about is whether or not their blog community gets blocked."

Although blogging is growing, it remains limited in terms of both scope and influence. As Mao points out, 300,000 (or for that matter even a million) bloggers in a country of 1.4 billion is not much in the way of a trend. And Xiao notes that it still takes a backseat to SMS and other means of peer-to-peer communications.

"It's certainly changing the current dynamic," he says, "but I would not say at this point that it's destabilizing the current dynamic." Yet this, he notes, may change.

"It's starting to, and will play a bigger and bigger role to influence the free flow of information and expression. You will see some crackdowns, you will see some services being shut off, you may even see some bloggers being arrested. But overall, the genie is out of the bottle."

Shares