I studied photography for three-quarters of my high school career. Some of this time was spent examining the work of Diane Arbus and Imogen Cunningham, but most of it was spent in the school's darkroom. The room was enormous, with two rows of enlargers flanking the walls and a long steel sink dominating the center. I would arrive early to mix the foul-spelling chemicals, always remembering to follow the mantra "Do what you oughta -- add the acid to the watah."

Chemicals mixed, the other students filed in, looking pale in the room's surprisingly bright yellow light. During some procedures, such as experiments with lithography, the yellow lights were switched off in favor of dim red bulbs. It would take my eyes several minutes to become accustomed to the light, but I didn't have to wait that long to get to work, the layout and contents of the room being so familiar.

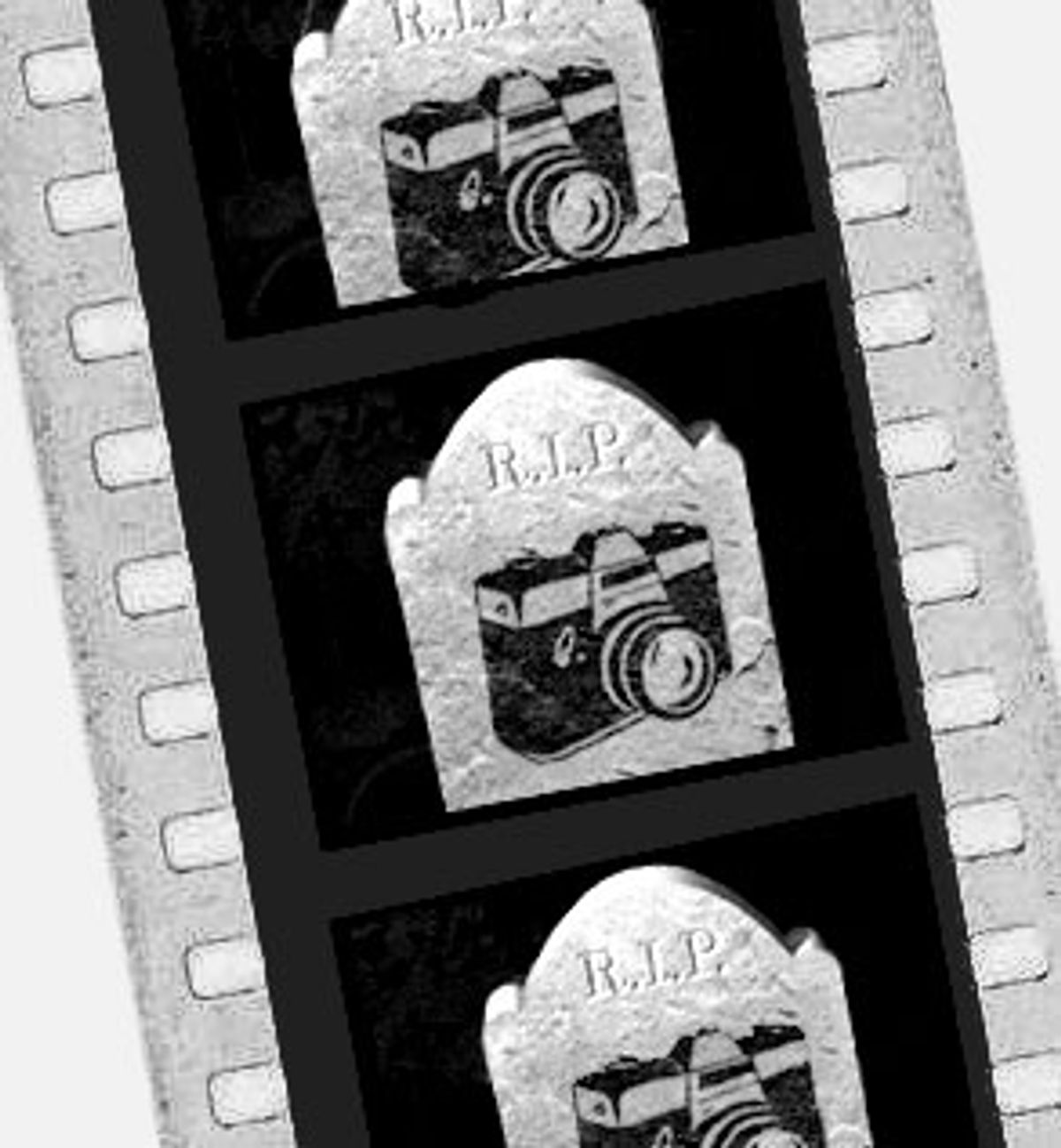

I don't know for sure, but I assume that the darkroom at my high school is gone, probably replaced with two rows of brightly colored iMacs loaded with Photoshop. Instead of learning how to increase grain by using hot water in the developer solution, I imagine today's students learn how to apply a filter to do so. Instead of handcrafting a piece of cardboard on a wire and waving it under the enlarger's light to soften an area of a print, they manipulate image layers in software.

Some of my most memorable hours of high school were spent in that darkroom, which I am sure sounds more than little pathetic. Sometimes as we worked on our projects, my fellow students and I would sing. One boy whose name I have since forgotten knew the words to countless James Taylor tunes. He would lead us in renditions of "Your Smiling Face" and "Carolina in My Mind" as we watched our images appear like magic in the plastic trays. Alone, I would sing Talking Heads or scat, with little regard for my inability to carry a tune, my volume, or the classrooms sharing the adjacent walls. When I walked into the bright light of the classroom to examine my print, Mrs. Phillips might shoot me a look, but that didn't matter. Morale in the darkroom was high, people were enjoying their time in her class, why would she squelch our joy?

In that darkroom, I fell in like with Amie Ellis-White, an older woman who already had a boyfriend called Drew. In that darkroom, I experimented with making poster-size prints and bas-relief black-and-white lithographs, and I watched world-wise surfer dude named James deftly craft a bong from aluminum foil. If the cops are coming, just ball it up, man.

Traditional darkroom photography is a dying art. If you were to rattle off a long list of reasons why digital photography is superior, I wouldn't argue with you -- it is superior, for a long list of reasons. But today's photography students, hunched in front of their rows of computers, don't get to sing in harmony while manipulating their pictures. I don't imagine that applying the Burn-In Filter can effect the level of joy that I felt using my hands to shape the light that streamed onto photo paper. For that reason alone, paper-and-chemical photography will never really die. Not because some curmudgeon refuses to give up his Bessler enlarger and his Underwood typewriter, but because there is art in the process of creating art. In hand-burning an underexposed corner, in crooning sappy songs while you work, in gliding through the pale yellow light. There's no Photoshop filter for that.

Shares