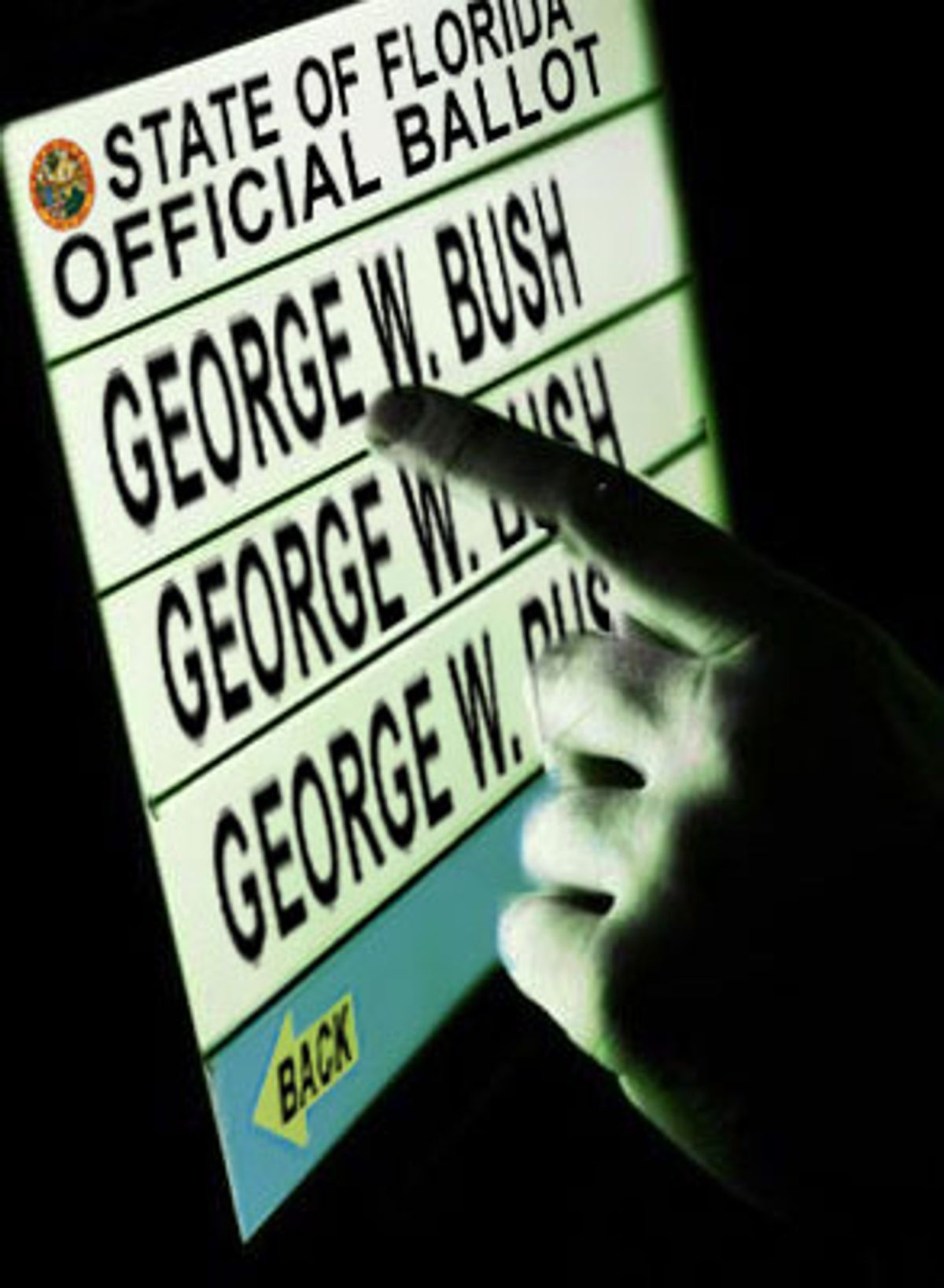

Lida Rodriguez-Taseff, a corporate lawyer and a former president of the Miami chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, vividly remembers the moment she became an election reform activist. It was on Sept. 10, 2002, when she saw yet another election in South Florida go unfathomably awry -- this time a primary election, the first vote in which her county, Miami-Dade, and several neighboring counties would use electronic voting machines at the polls.

"It was jarring," she recalls. The poll workers didn't know how to run the new touch-screen machines. The voters didn't know how to vote on the machines. Some of the systems didn't work at all; they displayed incorrect selections, froze up, acted generally odd. "What moved me to action was seeing all these people -- elderly black folks standing in line for hours without being able to vote, fanning themselves in the hot sun, waiting for the machines to start working so they could get their chance," Rodriguez-Taseff says. "And then, seeing the people coming out of the polls with their eyes dazed over, shocked and amazed by what had happened. They couldn't understand why when they pressed a button next to one candidate, the machine brought up another candidate's name."

Accounts of the perils of electronic voting systems are nothing new. In the last couple of years, it seems we've all heard stories like Rodriguez-Taseff's -- tales of machines breaking down during elections, of systems displaying erroneous selections, of machines behaving badly. When computer security experts have examined some of the voting machines now widely in use, they've discovered enormous security problems. In January, for instance, a team at RABA Technologies, a computer consulting firm in Maryland, managed to devise a half-dozen ways of compromising the votes in touch-screen machines manufactured by Diebold, which produces the systems to be used in Maryland and Georgia this year. (A PDF file of their report can be found here.) And who hasn't heard that voting machine firms may have close relationships with certain politicians? Diebold's CEO is famous online for declaring, in his role as a major Bush-Cheney fundraiser, that he's "committed to helping Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year."

According to the political consulting firm Election Data Services, on Election Day this year about 29 percent of the registered voters in the nation -- more than 45 million people -- will find electronic touch-screen systems at their polling places. To computer scientists, the only way to secure these machines is to have them print out "verifiable" paper ballots -- a paper ballot that a voter accepts or rejects as his accurate vote, and which is then counted in the case of a contested election. Such a system will only be available this year for the one-half of 1 percent of voters in Nevada. The rest of us will cast our electronic votes with a kind of leap of faith. We'll have no way of knowing what the machine has actually recorded, and we'll be forced to trust that the system (the officials, the voting company, the procedures, everyone and everything involved in the race) has done everything fairly. We have no choice, really, but to trust the system.

Still, two years after witnessing that Florida debacle, Rodriguez-Taseff, who founded and now heads the Miami-Dade Reform Coalition, a nonpartisan citizen's group dedicated to fixing elections in a county where elections seem eternally unfixable, remains deeply worried about the electronic systems that will be used at her polls this year. But she says that it's too late, too costly and probably not even technically feasible to configure voting machines to print the kind of verifiable ballots that computer scientists have called for, at least for this election. That kind of system, untested and unproven in any real race, "lives in outer space," Rodriguez-Taseff says bluntly.

What worries Rodriguez-Taseff are the far more pragmatic questions of voting procedures and voting practices we'll have to deal with in electronic polling places this year. She fears that polls won't open on time, and that voters won't know how to use the machines, and that officials won't know how to help voters when the machines (inevitably) screw up. She's also concerned that in the event of irregularities, elections laws in Florida won't allow a thorough examination of the machines to see what's gone wrong. The machines in her state are capable of printing out paper "ballot images" of each vote after the election; these ballot images aren't quite the same thing as the voter-verified paper trail that computer scientists have been calling for, but they would constitute some kind of paper record of every voter's choices, and Rodriguez-Taseff believes they could prove useful if there are questions about an election's accuracy. Florida's election rules, however, specifically prohibit manually recounting these ballot images, a situation that Rodriguez-Taseff says will cast even more doubt on election results.

She is also concerned that voters who've heard about the problems with electronic voting machines will disenfranchise themselves. In a recent poll of Florida voters conducted by Quinnipiac University, more than half of the people surveyed reported being less than fully confident that their votes would be counted at all during the upcoming election. The numbers were higher when broken out for minorities and Democrats in the state. About 16 percent of those surveyed said they planned to vote by absentee ballot, and half of them said they were choosing the absentee route because they didn't trust the voting machines.

Rodriguez-Taseff blames political parties -- specifically Democrats trying to court minority voters in Florida -- for this skepticism. She says the parties aren't doing enough to educate voters about what they'll see at the polls this year. Instead of being honest with voters about both the advantages and disadvantages of electronic voting, politicians are trying to paper over the problems, or to urge a quick-fix, not especially good alternative -- absentee voting.

But other voting experts charge that it's not the Democrats' or the Republicans' fault that people don't trust the election system -- it is, instead, the fault of activists who've been constantly criticizing the voting machines for the past two years. "The conversation the way they've been framing it is all going to make people believe that they shouldn't vote," says Ted Selker, a professor at MIT who co-directs the Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project, which produced a landmark study examining how voting technology performed in the 2000 election. He says that electronic voting critics have forced the electorate to become much more cynical and jaded about elections and especially about the integrity of elections officials.

And in an election this tight, is such skepticism something that political parties -- especially Democrats -- want or need? Most touch-screen machines in South Florida were introduced, after all, by Democratic officials who were horrified at the rate of disenfranchisement of minorities in the 2000 presidential vote; the machines were supposed to make voters come back to the polls, not keep them away. Clearly, though, either the machines, or the controversy surrounding the machines, is making people scared.

What if all the activism only succeeds in keeping people away from the polls on Election Day?

Just a few weeks after Florida's 2002 primary, when Salon first reported on the flawed machines and on some computer experts' concerns about the security and accuracy of electronic voting systems, just about everyone we spoke to in the election community told us not to worry. What happened in Florida's primary was caused by ill-prepared poll workers, not buggy machines, elections officials and voting companies said, and they maintained (and still maintain) that no votes were lost. It was said that computer scientists who fretted about electronic voting machines that aren't backed up by a "paper trail" were naive, and they didn't understand the rigorous security procedures that occur in real elections; people who suggested that we shouldn't trust our democracy to private firms were scoffed at, labeled conspiracy theorists.

Over the course of a couple of years, though, calls by elections officials and voting companies for us to remain unworried became almost comically blind to the problems at hand. There have been enough voting machine failures, scandals and exposés in that time to make any concerned citizen weep. These days, nobody can seriously call the critics of such systems naive conspiracy theorists. Thanks to their efforts, we now know that at voting firms such as Diebold, employees don't seem to take security very seriously, as internal documents from the firm seem to suggest; that executives at some companies have suspiciously close relationships with elected officials; and that despite assurances from elections officials, when you vote on an electronic machine, you might never know what the system has done with your choice.

No longer are the activists considered kooks and paranoids, and their fears, backed up by numerous studies pointing out flaws in some electronic voting machines, have thoroughly permeated the mainstream media. Magazines as diverse as the Nation, Vanity Fair and Hustler have devoted considerable space to the issue. In January, the New York Times inaugurated a special editorial page section aimed at "Making Votes Count," and Paul Krugman routinely uses his column to warn of the dangers of paperless electronic voting. When Rodriguez-Taseff's Miami-Dade Reform Coalition recently discovered that the county had lost all of its electronic records from the 2002 election, the news didn't break online, in a techie blog or underground discussion site, as it might have a year or two ago. Instead, the story landed on the front page of the Times.

The coverage has certainly helped convince the public, as well as elections officials, of the dangers of electronic systems. Officials in California, for instance, have mandated that electronic systems include verifiable paper ballots by 2006, and Congress is mulling over legislation to require such machines nationally. David Dill, the Stanford computer scientist who's done much to line up technologists against paperless electronic voting systems, says that he's exceedingly pleased with what critics of electronic voting machines have accomplished so far. When, in early 2003, Dill began asking computer scientists to sign a petition calling for verifiable voting systems -- that is, systems that produce some kind of human-readable physical evidence of a person's vote -- he didn't think he'd be able to convince entire states to change their rules.

But in the face of so much anti-e-voting rhetoric, are voters becoming unreasonably scared or suspicious of elections? They might be. While it's undeniable that Dill and other critics of electronic voting systems have sparked much-needed discussion and action to fix some of the glaring problems with electronic machines, experts like Selker worry the hype is unnecessarily scaring voters. Selker points out that in 2000, most of the votes that were lost because of equipment malfunction were caused by faulty ballot design (remember the "butterfly ballot"?), not faulty machines, and that by far the largest number of votes (several million) lost could be blamed on bad voter registration procedures. These problems should be fixed before we spend money on paper trails for touch-screen machines, Selker says.

While he understands people's trepidation about voting on a system that doesn't have a paper trail, Selker insists that rigorous testing can detect malicious code in paperless voting systems. He recommends, for instance, that elections officials conduct "parallel testing" on voting machines -- on Election Day, they would randomly visit precincts and pull certain machines out of service for the day, then subject those machines to a battery of tests. If those randomly selected machines are found to record and tabulate votes accurately, you can be reasonably sure that the other machines are doing the same thing. (Officials in California are expected to conduct parallel testing on Election Day, as will some officials in electronic voting counties scattered all over the nation. In Maryland, where the choice to go to Diebold machines has sparked several security reviews and a lawsuit calling on a court to prevent the state from using the system, officials are considering using the parallel testing, said Linda Lamone, the administrator of Maryland's Board of Elections.) With such measures in place, Selker says, people can be confident that the electronic machines are working properly. "It'd be terrible if the reason we didn't have a great election is because Americans acted like voters in a Third World country" and didn't trust what happened at the polling place, he says.

David Dill, for his part, insists that it was never his intention to cause people to stay away from the polls, and he says he always tries to let people know that the problems with voting machines are no excuse not to vote. "People have to vote," he says. "I'm not sure how to get that message across. I wouldn't be going to all this trouble to make sure we have a trustworthy election system if I didn't respect the importance of voting." He also emphasized that "we're not talking about a proven conspiracy to steal the election with electronic voting. I'm sure that there'll be some people saying such things, but what I've been saying all along is we should pick the best technology we have available and use that."

There is something of an inconsistency to what Dill says, however. On the one hand, he's insisting that elections can't be trusted unless they're conducted on equipment that produces some kind of verifiable paper trail. At the same time, he's telling voters that they should probably go ahead and vote on machines that don't produce such a trail, machines that he says can't be trusted. Now, most people will probably disregard this inconsistency and, even if they agree with Dill that the machines are flawed, they'll still go ahead and vote. As Dill says, this year's election is far too important to miss out on. But there are probably a fair number of people who are on the fence about voting to begin with -- young people, say, or certain minorities, or members of other groups that tend to vote in low numbers, possibly because they don't think voting will make any real difference to their lives. Dill's suggestion that the voting system is not trustworthy just adds another reason for them to doubt the importance of voting -- and for how many people will it be the deciding factor, the final straw keeping them home on Election Day?

Some Democrats are, understandably, nervous about this idea. Dill says that he's heard from party officials who tell him privately that they support him, but that they couldn't support the cause publicly for fear that it will turn voters away. In Florida, the party is giving voters mixed signals about what they should do. It won't say that the machines are buggy, or that people shouldn't trust them. Yet it has also supported a call for a paper trail. When asked about the party's position, Allie Merzer, a spokeswoman for the Florida Democratic Party, said, "We advocate for any system that increases voter confidence. All voters should have the right to have their vote counted." Merzer said that "in some instances" people had "valid" concerns about electronic voting machines. People who are concerned should vote using other methods, she suggested -- absentee ballots or early voting. In light of people's concerns, the party is "ramping up" its effort to sign people up for absentee ballots, Merzer said.

"Stupid Democrats -- with Democrats as dumb as this who needs Republicans?" counters Lida Rodriguez-Taseff. "They're running around afraid of their own shadows, not talking about the problems with the voting machines, thinking they can lie and manipulate the African-American community into voting for them."

Instead of being mealy-mouthed about the situation, Rodriguez-Taseff would like the Democrats to directly acknowledge and make clear to voters the problems associated with electronic machines. Only when it does this will the party be able to fix the problems, she says. And she thinks that a direct approach will bring more voters to the polls: "They should reach deep into the history of this situation," she says. "They really should be saying, 'Look, the lynch mob didn't scare you away from voting. Poll taxes didn't scare you away. Literacy tests didn't scare you away. Are you going to let a little voting machine scare you away?' Voting is a sign of defiance and courage. Voting at a voting machine even when the voting machine doesn't work is a sign of courage. But instead, they're choosing to lie to people. 'No, the lynch mob is not outside.' 'Oh yeah, your vote will be counted -- just vote for us.' People aren't stupid. And that's why people aren't going to go to the polls, because they're being lied to."

Rodriguez-Taseff also took issue with the Democrats' suggestion that people should vote using absentee ballots instead of going to the polls. Absentee ballots are not known to be any safer than electronic voting systems. Yes, there's a paper ballot -- but it can easily be thrown away, lost, misfiled, damaged, never counted, or be subjected to any number of other harms, whether intentional or accidental. Of course, there are security precautions to prevent these things; but if you're the sort of person who is wary about the security precautions meant to prevent electronic vote fraud, why wouldn't you be similarly wary of the precautions meant to prevent absentee-ballot vote fraud?

Rodriguez-Taseff says that she doesn't intend to vote absentee. With all that can go wrong with such a ballot, she'd prefer to take her chances with the computer. Ted Selker of MIT says the same thing. Indeed, Selker recounted a time he witnessed an incident of absentee ballot tampering in his own voting precinct in Massachusetts. After he cast his vote on one Election Day, he noticed a woman (probably an elections official or poll worker) sitting to the side, looking over a stack of ballots. He asked her what she was doing. "I'm checking the absentee ballots," the woman said, explaining that she was making sure that they were in good enough condition to be filed into the ballot reader. Selker asked her if she'd found any problems. "So she tells me, 'One of them couldn't be read, so I looked at it and I found a mark that wasn't right and I erased it,'" Selker says. "So you see, she changed somebody's ballot without anyone else's permission, on her own. And she admitted it to me. That's what I think about absentee ballots."

David Dill's home precinct in California uses a paper-based optical scan voting system, not an electronic touch-screen. If it did use a touch-screen, would he vote absentee? Dill is aware of the problems with absentee ballots, and choosing between absentee voting and paperless touch-screen voting would be especially difficult, he says. In the end, though, Dill says that he would probably take his chances with the absentee ballot. Rebecca Mercuri, the computer scientist who first developed the idea of a verified paper ballot and is quite skeptical of any machines that lack such a system, says that she, too, would vote absentee instead of on a touch-screen.

One of the few political groups that seems to have no deep division or concern about how people should vote in the upcoming election is the Republican Party. At both national and local levels, the GOP is consistent about what people should do -- they should go to the polls and vote, and they should trust their touch-screens. It is true that in July, the Florida Republicans sent some voters a flier urging them to register for absentee ballots. "The liberal Democrats have already begun their attacks and the new electronic voting machines do not have a paper ballot to verify your vote in case of a recount," said the flier, which featured a picture of President Bush. "Make sure your vote counts. Order your absentee ballot today." But the party immediately repudiated that message. Everything else that Republican officials -- including Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and Glenda Hood, the Republican secretary of state -- have said indicates a deep trust in the elections systems as they are.

"That flier most definitely caused confusion," said Joseph Agostini, a spokesman for the Republican Party of Florida. He said that the person responsible for that confusion has "learned the hard way" what the Florida Republicans actually think about electronic voting. "It's something we regret that went out, and we've taken steps to make sure that this misunderstanding doesn't occur again," Agostini said. "Let me say without any uncertainty that we the Republican Party have complete confidence in the Florida election system and its accuracy. Whether it's opti-scan or touch-screen by Diebold, we have no doubts that the election will run smoothly."

If you're concerned with the security of electronic voting systems but you decide to vote on such a machine anyway, you can perhaps rest a bit easier this year, as the controversy surrounding the machines has already led to many extra security safeguards protecting the systems. In large part due to the activists' complaints over the lack of a paper trail, some of the most ill-regarded machines and manufacturers have been subjected to punishing scrutiny. Diebold's machines, for instance, have been thoroughly inspected by several computer researchers, and while many of the researchers found significant problems with the machines, it is at least comforting to know that elections officials and the company made some improvements to the systems. In Maryland, for example, the state and Diebold have implemented many of the safeguards proposed by RABA, a computer firm that found significant vulnerabilities in the Diebold system earlier this year. Linda Lamone, Maryland's election administrator, says that while she has not enjoyed being the subject of intense criticism over her decision to use Diebold's machines, "I like the opportunity to make things better."

Facing similar pressures from critics of electronic voting systems, Nevada Secretary of State Dean Heller decided last December to make his state the first in the nation to use paper-equipped touch-screen systems. The machines he chose are manufactured by Sequoia Voting Systems, and for the most part they work exactly how proponents of such systems have said all touch-screen systems should work: When a voter steps up to the system and casts a ballot on the touch-screen machine, a printer attached to the machine produces a ballot for the voter to review. (The ballot is printed under a glass screen in order to prevent the voter from walking off with it.) After the voter reviews this paper ballot, he or she can either accept or reject it on the touch-screen; either way, the ballot scrolls away into a locked compartment, and it's then considered the voter's official ballot, trumping whatever electronic ballot the touch-screen machine has stored. In the event that a recount is needed, the paper ballot tape would be counted by hand, and that count would become the ultimate election result, said Alfie Charles, a spokesman for Sequoia.

David Dill and Rebecca Mercuri say they're hopeful that the Nevada test will go well, but both said they thought there'd probably be some mishaps in the state, as there always are in such things. "I do not want the future of the paper-trail movement to be judged on how the machines do in Nevada," Dill said, though he conceded that this would probably happen. If the election in Nevada goes badly, people on the other side of the paper-trail debate will surely point to the race as proof that paper-trail systems can't work.

And, who knows, maybe they'd be right. Indeed, Mercuri said that she's been thinking for some time that even electronic machines equipped with a paper trail "are probably not the best way to vote," because "the touch-screen puts something between the voter and the actual construction of their ballots." For most able-bodied voters, both Mercuri and Dill said, fill-in-the-bubble optical-scan paper ballots are probably the best way to vote.

Many groups and both political parties plan to monitor polling places this year, and given the scrutiny they'll face, you can be sure that any irregularity, no matter how small, will be taken very seriously by officials. Verified Voting, David Dill's group, is calling for technically inclined people to volunteer to monitor precincts across the nation. Verified Voting is also creating a Web-based national error-reporting system, a central clearinghouse for people to report everything that goes wrong on Election Day; this will allow the group to spot when similar problems occur in different locations, say, or to keep track of a specific sort of glitch, giving activists a fuller picture of what happens on Election Day.

In Maryland, Linda Schade, the activist who has sued the state to prevent the Diebold machines from being used in November, says that in the event her suit is unsuccessful, she and her fellow Diebold critics will closely scrutinize what happens on Nov. 2. "I want to have a handful of people at every precinct dedicated to helping people, making sure they know what's going on, that all races are on the ballots, that voters go in with the information they need, and that there are people on hand when there are problems," she says.

Schade says she hopes everything goes well. But what if it doesn't? What if, for example, there's an unexpected result -- what if Maryland, which looks sure to choose Kerry, goes for Bush? Will anyone trust the machines?

In the end, that's the only real test of a voting system. Do people believe what it says, even when what it says seems unbelievable? "If we wake up the next day and Maryland has gone for Bush ...." Schade says, and her voice trails off. There's nothing more to say. The truth is, nobody really knows what will happen then.

Shares