Carleton S. Fiorina's fall from grace was dramatic, as was most of her career. But don't cry for Carly; her way of doing business remains ascendant, and has already triumphed over that quaint set of humanistic values known as "The HP Way."

I well remember my first meeting with Carly, who from an early date seemed destined to be one of those first-name-only stars like Cher or Madonna. Months before Hewlett-Packard named her its chief executive, the company had invited me and John Markoff, my friend and colleague at the New York Times, to spend a day with the engineers at its legendary research labs. But midway through our morning in nerd nirvana, Carly paid us a "surprise" visit.

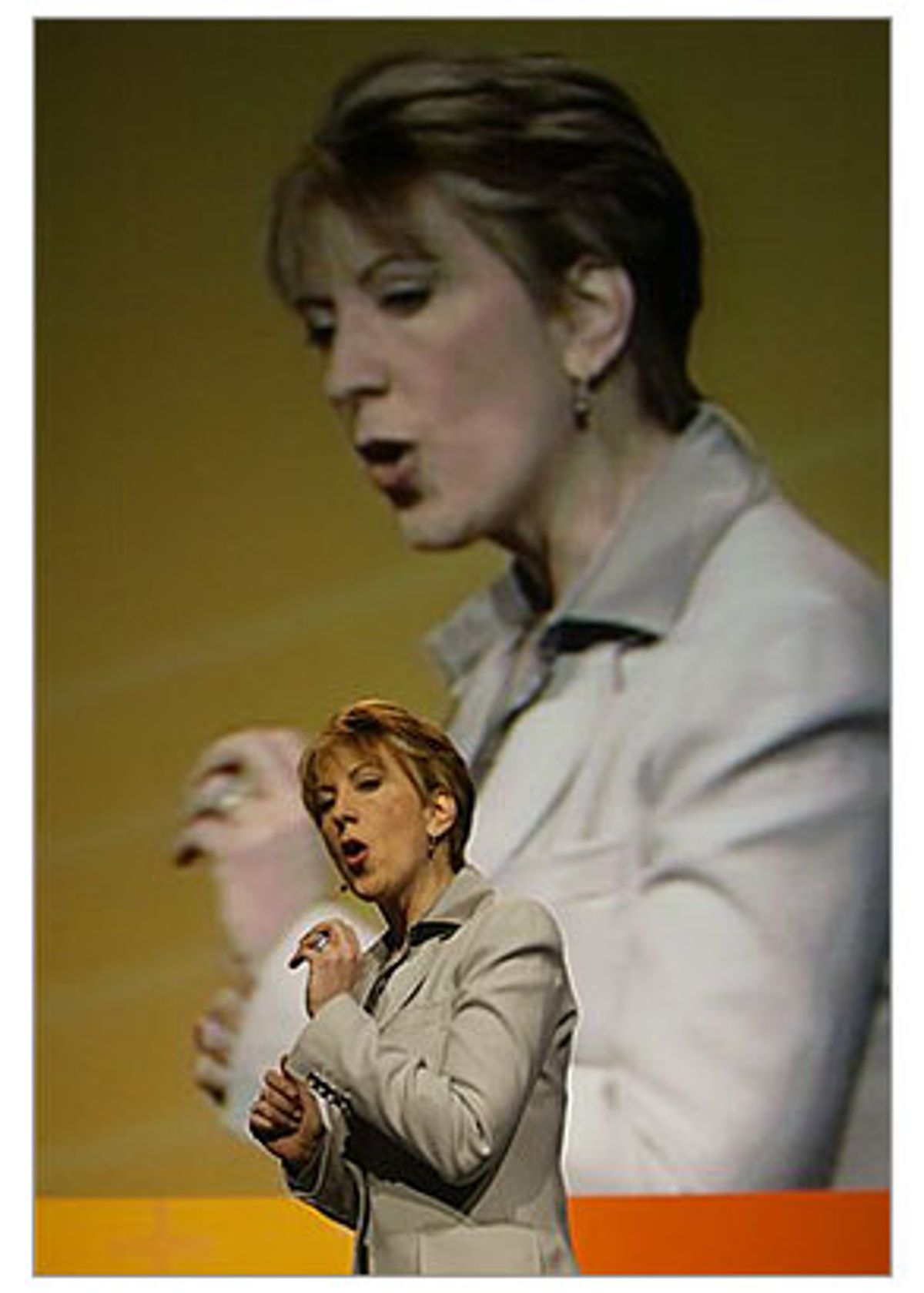

She was, of course, charming, well-coiffed and coutured, as nearly every article at the time would mention. And as I watched her perform, amid an awkward group of guys who really were wearing short-sleeved sta-press shirts with pocket protectors, I realized I was seeing the new and old faces of Silicon Valley, up close and personal.

On one side of the hall were these unassuming but enormously bright individuals who came to work each day on Page Mill Road, in Palo Alto, Calif., not to make a killing in high tech, but for the sheer joy of inventing cool things. On the other was the perfect pitch person, singing Wall Street's tune absolutely in key.

From early in her six-year reign, Carly's mendacity was breathtaking, as she methodically eviscerated HP of everything the company once stood for. Is that too harsh? Recall the "invent" campaign, launched soon after she joined, where she plastered billboards and ads with the image of Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard's sainted Palo Alto garage, even as she was slashing the company's research budget and laying off scores of real-life inventors. After all, tinkering with the outer reaches of particle physics may be cool, but it's hardly a bottom-line contributor, not this quarter anyway.

At the same time, the truly inventive side of Hewlett-Packard, as well as its historical heritage, was being spun off as a separate company, now known as Agilent. To be fair, HP's board initiated this thrilling bit of stupidity before hiring Carly, but she had plenty of time to stop it and did not.

HP's test and measurement instruments, direct descendants of the audio oscillators that launched the company in 1939, were and are considered the best that money can buy. Despite increasing global competition, these products command a premium price and maintain high profit margins because they are simply higher performing, better built and more innovative than the offerings of other companies. They are, in a word, "differentiated."

Yet Carly and the HP board chose to dump this profitable business to concentrate on commodity products like printers and PCs. Why? The answer at the time was that securities analysts accustomed to following straightforward companies such as Dell Computer really couldn't understand a complex business like test and measurement. And, to be sure, Wall Street's shills fell into lockstep, praising the divestiture as a brilliant strategic move that would, in that tired phrase, increase shareholder value.

As HP's best and brightest headed for the doors, whether they jumped or were pushed, some of them were not shy about calling a reporter who had covered the company for many years. As I talked to these talented people from every level of the company, one interpretation of events emerged with remarkable consistency. Carly had no intention of sticking around Hewlett-Packard for very long, these folks said. Her real intent was to do a quick, Lee Iacocca-style turnaround, accompanied by the best autobiography money could buy, and in 2004 run for the U.S. Senate, against Barbara Boxer.

It seemed a little far-fetched, but soon the photo-op shots of Carly in the company of high-ranking Republicans began proliferating. Even as Carly's script for HP ran into harsher realities, even as Boxer retained her seat, the story never really died. And in retrospect, it offers the only explanation that makes any sense at all of Carly's biggest strategic move. I'm referring here to the acquisition of the Compaq Computer Corp.

Prior to launching that deal, Carly had said her intention was to pattern HP after Lou Gerstner's version of IBM, which had successfully leveraged its low-margin hardware business to sell high-margin consulting services. To that end, she initially negotiated to acquire the consulting arm of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the global accounting firm. She punted at the last minute, and IBM ultimately acquired PwC's jilted consultants at a substantial discount.

Undaunted, in 2002 Carly moved to acquire Compaq, which was bleeding market share to Dell and losing money at an even faster rate than HP's PC business. Never mind that no big merger in the history of high tech had ever really worked; never mind that Compaq itself had already made two big acquisitions -- Digital Equipment Corp. and Tandem Computer -- that had failed to add any value; never mind that Dell rapidly seized on the inevitable uncertainty to take even more customers away from both HP and Compaq. Even the pointed opposition of founder's son Walter Hewlett didn't dissuade Carly and the HP board from this historic blunder.

At the time, I was on staff at a consulting firm that was retained by one of the family foundations to analyze the merger. In the process, we spoke with a number of people close to both companies and their remarks were stunning. "The collision of two garbage trucks," was how one put it. "Doubling down on a dog," was another take. Without naming the firm, or their specific recommendations, it was obvious to anyone who cared to look that Carly's projections could only materialize if IBM, Dell and Sun Microsystems took a collective nap for the next five years, and every single one of her rosiest scenarios came true at once. Any resemblance to the Bush budget is entirely coincidental, I'm sure.

So why did she do it? For one reason: Wall Street loves big mergers. The investment banks collect immense fees for their roles as advisors, regardless of the ultimate soundness of the deal. And their securities analysts all write positive reports, which prompt a lot of rubes to buy shares, which generates a flood of trading commissions. Big mergers and acquisitions are almost always a net negative for the companies and communities involved, but a win-win for the bankers, lawyers and other deal makers.

A second reason is that it should have worked well enough for Carly to declare victory and move on to the political stage. Despite their dismal long-term success record, big mergers usually can "achieve synergies," Wall Street-speak for massive layoffs, which reduce costs enough to show a big if fleeting bump in earnings per share.

There was a brief period where the credulous might have believed that this merger was working, thanks entirely to such redundancies eliminated and other corporate bloodletting. But it didn't last, as Carol Loomis' masterful article in last week's Fortune magazine made all too clear. Loomis did the tough analytical work that the board should have done, published it for all to see, and in the end, HP's recalcitrant directors had to act.

To those who will inevitably say that Carly has been singled out for harsh treatment because she is a woman, nonsense. Anne Mulcahy of Xerox, Meg Whitman of eBay and Carol Bartz of Autodesk, among others, have all shown that a Y chromosome is no prerequisite to performing the CEO's role with quiet competetence. What these leaders share besides their gender is they don't make promises they can't possibly keep.

As the Fortune article makes clear, Carly's numbers didn't work because they couldn't work, which is of course what folks like Walter Hewlett were saying three years ago. And so a once great company is a shadow of its former self, and Fiorina is out of a job. But don't cry for Carly. Given her way with numbers, there's surely a spot for her in the Bush administration. Secretary of the treasury, perhaps.

Shares