One day, Tom Ridge is running the Department of Homeland Security. The next day, he's working for a company that supplies high-security technology to the Department of Defense. No surprise there. The revolving door between the Bush administration and private companies that profit from the government seems to be a trademark of this White House.

On Tuesday, Ridge was named to the board of directors of Savi Technology, a privately held Sunnyvale, Calif., multinational. The company supplies RFID (radio frequency identification technology) to the U.S. military. It's used to track and manage shipments of supplies and equipment to American forces in Iraq and elsewhere around the world.

In his new role, Ridge will be the latest and most high-profile RFID evangelist. "It's clear his experience and expertise in government and Homeland Security ... will be a great contribution to our strategies and developments," says Mark Nelson, a Savi spokesperson.

It was certainly savvy to sign up Ridge to endorse RFID, as the technology has many controversial applications. The Bush administration is in the process of adopting RFID technology as a way to keep track of not just things but also people.

The storm over the technology erupted when libraries adopted it to track books. Privacy advocates argued that it could be abused to monitor patrons and what they read, spawning any number of suspicions about them.

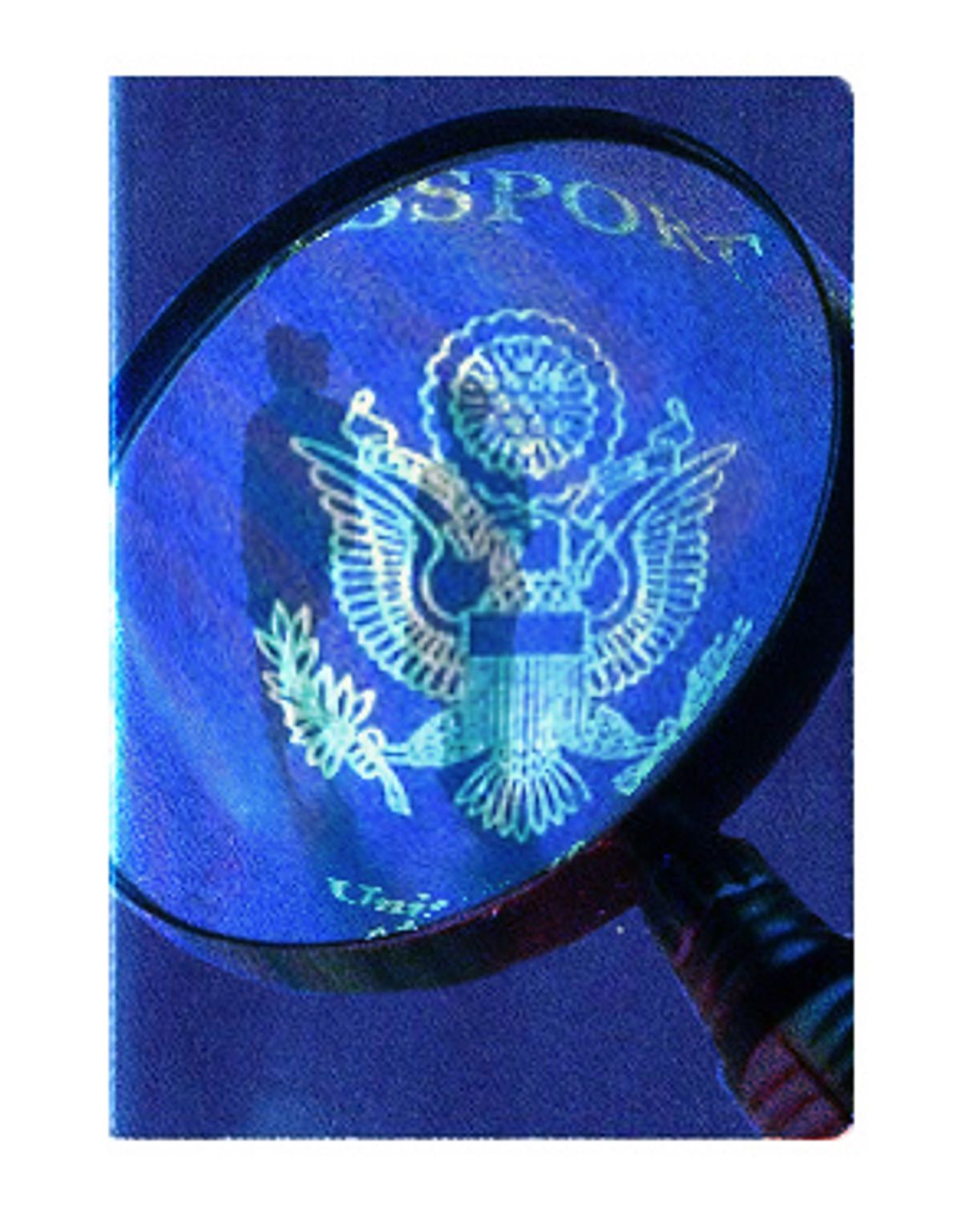

Today, civil libertarians are up in arms over the State Department's intention to use RFID in U.S. passports, beginning this year. "It is the government and the private sector joining together as usual to create and deploy surveillance technologies," says Lee Tien, an attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which, along with the American Civil Liberties Union, sent copious comments to the State Department critiquing the plan to use the technology for passports. "It's all one big happy family as far as they're concerned. Unfortunately for everyone else concerned, it is just one great big surveillance industrial complex."

"It's mildly entertaining that just as we're seeing a massive push for RFID and tracking chips in everything, the first Bush appointee to Homeland Security just happens to be involved," says Bill Scannell, a privacy activist who put up the site RFID Kills.com last week to oppose the use of the technology in passports. "It all goes to the heart of what happens when people get treated like bottles of shampoo getting shunted around the supply chain from warehouse to warehouse. This is the Bush administration's approach to security. And it doesn't work. It's great for shampoo. It's bad for people."

The new "electronic passports" will be equipped with a chip capable of transmitting personal information -- such as your name, nationality and address -- found on standard passports. The State Department contends that the chips will bring a new level of security to American passports, making them easier to process at border crossings and harder to forge. But privacy advocates and civil libertarians argue that it will achieve exactly the opposite result: exposing American citizens to having their personal information read or stolen without their passport ever leaving their hands.

Beth Givens, director of the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, a privacy rights group, says: "The reason that I am so concerned about the passport RFID issue is that individuals have no choice in the matter. If they want to travel beyond the borders of the United States they must carry a passport. So, they are going to be forced to carry a tracking technology with them whenever they go."

The reason RFID is more controversial than, say, a bar code is that the data on the chip is read by a remote reader. The State Department asserts that the tags it will use can be read from only 4 inches away. But privacy advocates say there's no way the State Department can guarantee that.

As security expert Bruce Schneier writes on his blog: "Unfortunately, RFID chips can be read by any reader, not just the ones at passport control. The upshot of this is that travelers carrying around RFID passports are broadcasting their identity. Think about what that means for a minute. It means that passport holders are continuously broadcasting their name, nationality, age, address and whatever else is on the RFID chip. It means that anyone with a reader can learn that information, without the passport holder's knowledge or consent. It means that pickpockets, kidnappers and terrorists can easily -- and surreptitiously -- pick Americans or nationals of other participating countries out of a crowd."

There are no plans to encrypt the data on the tags in passports. "This is a dangerous, inappropriate device to be installing in U.S. passports," says Scannell, who imagines terrorists overseas identifying Americans by their passports when picking targets to bomb. "Which cafe do we lob the grenade into? Ping, ping, ping. There are 21 Americans in there." The tags could also be used to identify people who walk into an abortion clinic, a mosque or a political meeting.

Tags are being tested in other areas that concern civil liberties advocates. The Department of Homeland Security is experimenting with them as a way to monitor foreign visitors at U.S. border crossings. Electronic tags placed in visas and passports may speed up customs lines and identify suspects on government watch lists. But they could also expose travelers to invasions of privacy. Meanwhile, the Texas Legislature is considering allowing RFID to be placed in cars to ensure that drivers have valid insurance.

RFID has long been used for supply-chain management, both by business and the government. The Department of Defense uses Savi's technology to manage equipment and supplies in 40-foot-long shipping containers. "Picture hundreds if not thousands of containers in the desert," explains Savi spokesperson Nelson. "And workers need to find milk or boots or bullets. Rather than opening up each container, they can take a handheld device and scan those mountains of containers and find it." He adds that the company has had a relationship with the Department of Defense for nearly a decade, though he refuses to disclose what percentage of its business stems from Pentagon.

Savi is not among the companies competing to supply the RFID technology for U.S. passports. Besides, proponents of the technology stress that the implementation of RFID used in the desert to track military equipment has more in common with an EZ-Pass automatic toll crossing than what would be used in passports. Perhaps new hire Ridge, with all of his homeland experience, can help Savi bridge the gap between the battlefield and the border crossing.

Shares