Andrea Fleeks almost never had to bother with the blue blazer these days. Back at the height of the dot-boom, she'd put on her business journalist drag -- blazer, blue sailcloth shirt, khaki trousers, loafers -- just about every day, putting in her obligatory appearances at splashy press conferences for high-flying IPOs and mergers. These days, it was mostly work at home or one day a week at the San Jose Mercury's office, in comfortable light sweaters with loose necks and loose cotton pants that she could wear straight to yoga after shutting her PowerBook's lid.

Blue blazer today, and she wasn't the only one. There was Morrow from the NYT's Silicon Valley office, and Spetzer from the WSJ, and that despicable rat-toothed jumped-up gossip columnist from one of the U.K. tech-rags, and many others besides. Old home week, blue blazers fresh from the dry-cleaning bags that had guarded them since the last time the NASDAQ broke 4000.

The man of the hour was Landon Kettlewell -- the kind of outlandish prep-school name that always seemed a little made up to her -- the new CEO and front for the majority owners of Kodak/Duracell. The despicable rat-toothed Brit had already started calling them Kodacell. Buying the company was pure Kettlewell: shrewd, weird and ethical in a twisted way.

"Why the hell have you done this, Landon?" Kettlewell asked himself into his tie-mic. Ties and suits for the new Kodacell execs in the room, like surfers playing dress-up. "Why buy two dinosaurs and stick 'em together? Will they mate and give birth to a new generation of less-endangered dinosaurs?"

He shook his head and walked to a different part of the stage, thumbing a PowerPoint remote that advanced his slide on the jumbotron to a picture of a couple of unhappy cartoon brontos staring desolately at an empty nest. "Probably not. But there is a good case for what we've just done, and with your indulgence, I'm going to lay it out for you now."

"Let's hope he sticks to the cartoons," Rat-Toothed hissed beside her. His breath smelled like he'd been gargling turds. He had a not-so-secret crush on her and liked to demonstrate his alpha-maleness by making half-witticisms into her ear. "They're about his speed."

She twisted in her seat and pointedly hunched over her PowerBook's screen, to which she'd taped a thin sheet of polarized plastic that made it opaque to anyone shoulder-surfing her. Being a halfway attractive woman in Silicon Valley was more of a pain in the ass than she'd expected, back when she'd been covering rustbelt shenanigans in Detroit. California was full of pretty girls, right? But that was the other California, south of San Luis Obispo, the part of the state where the women shaved their pits and straightened their hair.

The worst part was that Rat-Toothed's reportage was just spleen-filled editorializing on the lack of ethics in the valley's boardrooms (a favorite subject of hers, which no doubt accounted for Rat-Toothed's fellow-feeling), and it was also the crux of Kettlewell's schtick. The spectacle of an exec who talked ethics enraged Rat-Toothed more than the vilest baby-killers. Rat-Toothed was the kind of revolutionary who liked his firing squads arranged in a circle.

"I'm not that dumb, folks," Kettlewell said, provoking a stagey laugh from Rat-Toothed. "Here's the thing: the market had valued these companies at less than their cash on hand. They have twenty billion in the bank and a sixteen billion dollar market-cap. We just made four billion dollars, just by buying up the stock and taking control of the company. We could shut the doors, stick the money in our pocket, and retire."

Andrea took notes. She knew all this, but Kettlewell gave good soundbite, and talked slow in deference to the kind of reporter who preferred a notebook to a recorder. "But we're not gonna do that." He hunkered down on his haunches at the edge of the stage, letting his tie dangle, staring spacily at the journos and analysts. "Kodacell is bigger than that." He'd read his e-mail that morning then, and seen Rat-Toothed's new moniker. "Kodacell has goodwill. It has infrastructure. Administrators. Physical plant. Supplier relationships. Distribution and logistics. These companies have a lot of useful plumbing and a lot of priceless reputation.

"What we don't have is a product. There aren't enough buyers for batteries or film -- or any of the other stuff we make -- to occupy or support all that infrastructure. These companies slept through the dot-boom and the dot-bust, trundling along as though none of it mattered. There are parts of these businesses that haven't changed since the fifties.

"We're not the only ones. Technology has challenged and killed businesses from every sector. Hell, IBM doesn't make computers anymore! The very idea of a travel agent is inconceivably weird today! And the record labels, oy, the poor, crazy, suicidal stupid record labels. Don't get me started.

"Capitalism is eating itself. The market works, and when it works, it commodifies or obsoletes everything. That's not to say that there's no money out there to be had, but the money won't come from a single, monolithic product line. The days of companies with names like 'General Electric' and 'General Mills' and 'General Motors' are over. The money on the table is like krill: a billion little entrepreneurial opportunities that can be discovered and exploited by smart, creative people.

"We will explore the problem-space of capitalism in the twenty-first century. Our business plan is simple: we will hire the smartest people we can find and put them in small teams. They will go into the field with funding and communications infrastructure -- all that stuff we have left over from the era of batteries and film -- behind them, capitalized to find a place to live and work, and a job to do. A business to start. Our company isn't a project that we pull together on, it's a network of like-minded, cooperating autonomous teams, all of which are empowered to do whatever they want, provided that it returns something to our coffers. We will explore and exhaust the realm of commercial opportunities, and seek constantly to refine our tactics to mine those opportunities, and the krill will strain through our mighty maw and fill our hungry belly. This company isn't a company anymore: this company is a network, an approach, a sensibility."

Andrea's fingers clattered over her keyboard. Rat-Toothed chuckled nastily. "Nice talk, considering he just made a hundred thousand people redundant," he said. Andrea tried to shut him out: yes, Kettlewell was firing a company-full of people, but he was also saving the company itself. The prospectus had a decent severance for all those departing workers, and the ones who'd taken advantage of the company stock-buying plan would find their pensions augmented by whatever this new scheme could rake in. If it worked.

"Mr Kettlewell?" Rat-Toothed had clambered to his hind legs.

"Yes, Freddy?" Freddy was Rat-Toothed's given name, though Andrea was hard pressed to ever retain it for more than a few minutes at a time. Kettlewell knew every business journalist in the Valley by name, though. It was a CEO thing.

"Where will you recruit this new workforce from? And what kind of entrepreneurial things will they be doing to 'exhaust the realm of commercial activities'?"

"Freddy, we don't have to recruit anyone. They're beating a path to our door. This is a nation of manic entrepreneurs, the kind of people who've been inventing businesses from video arcades to photomats for centuries." Freddy scowled skeptically, his jumble of grey tombstone teeth protruding. "Come on, Freddy, you ever hear of the Grameen Bank?"

Freddy nodded slowly. "In India, right?"

"Bangladesh. Bankers travel from village to village on foot and by bus, finding small co-ops who need tiny amounts of credit to buy a cellphone or a goat or a loom in order to grow. The bankers make the loans and advise the entrepreneurs, and the payback rate is fifty times higher than the rate at a regular lending institution. They don't even have a written lending agreement: entrepreneurs -- real, hard-working entrepreneurs -- you can trust on a handshake."

"You're going to help Americans who lost their jobs in your factories buy goats and cellphones?"

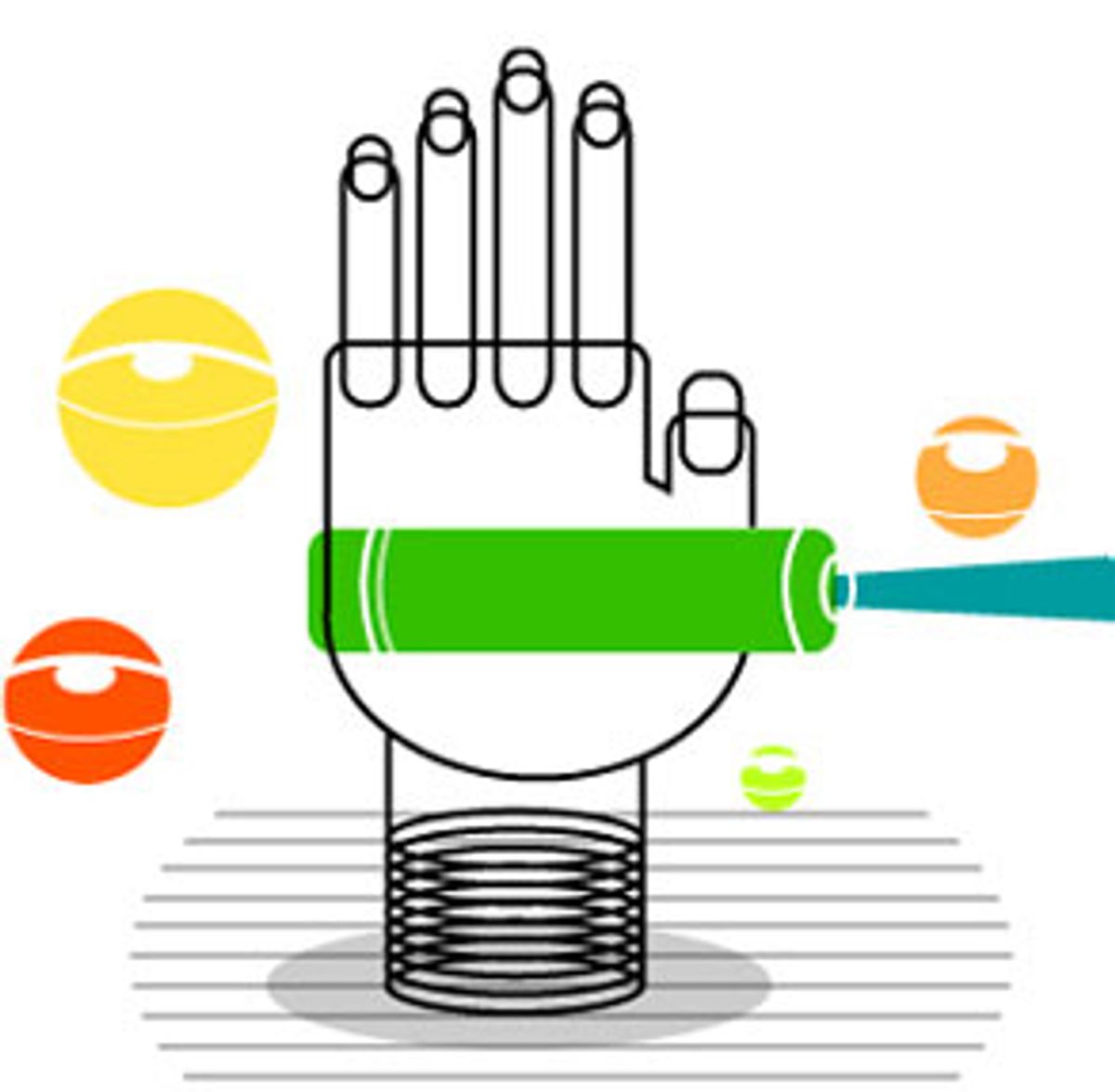

"We're going to give them loans and coordination to start businesses that use information, materials science, commodified software and hardware designs, and creativity to wring a profit from the air around us. Here, catch!" He dug into his suit-jacket and flung a small object towards Rat-Toothed, who fumbled it. It fell onto Andrea's keyboard.

She picked it up. It looked like a keychain laser-pointer, or maybe a novelty light-saber.

"Switch it on, Andrea, please, and shine it, oh, on that wall there." Kettlewell pointed at the upholstered retractable wall that divided the hotel ballroom into two functional spaces.

Andrea twisted the end and pointed it. A crisp rectangle of green laser-light lit up the wall.

"Now, watch this," Kettlewell said.

NOW WATCH THIS

The words materialized in the middle of the rectangle on the distant wall.

"Testing one two three," Kettlewell said.

TESTING ONE TWO THREE

"Donde esta el bano?"

WHERE IS THE BATHROOM

"What is it?" said Andrea. Her hand wobbled a little and the distant letters danced.

WHAT IS IT

"This is a new artifact designed and executed by five previously out-of-work engineers in Athens, Georgia. They've mated a tiny Linux box with some speaker-independent continuous speech recognition software, a free software translation engine that can translate between any of twelve languages, and an extremely high-resolution LCD that blocks out words in the path of the laser-pointer.

"Turn this on, point it at a wall, and start talking. Everything said shows up on the wall, in the language of your choosing, regardless of what language the speaker was speaking."

All the while, Kettlewell's words were scrolling by in black block caps on that distant wall in crisp, laser-edged letters.

"This thing wasn't invented. All the parts necessary to make this go were just lying around. It was assembled. A gal in a garage, her brother the marketing guy, her husband overseeing manufacturing in Belgrade. They needed a couple grand to get it all going, and they'll need some life-support while they find their natural market.

"They got twenty grand from Kodacell this week. Half of it a loan, half of it equity. And we put them on the payroll, with benefits. They're part freelancer, part employee, in a team with backing and advice from across the whole business.

"It was easy to do once. We're going to do it ten thousand times this year. We're sending out talent scouts, like the artists and representation people the record labels used to use, and they're going to sign up a lot of these bands for us, and help them to cut records, to start businesses that push out to the edges of business.

"So, Freddy, to answer your question, no, we're not giving them loans to buy cellphones and goats."

Kettlewell beamed. Andrea twisted the laser-pointer off and made ready to toss it back to the stage, but Kettlewell waved her off.

"Keep it," he said. It was suddenly odd to hear him speak without the text crawl on that distant wall. She put it in her pocket and reflected that it had the authentic feel of cool, disposable technology: the kind of thing on its way from a startup's distant supplier to the schwag bags at high-end technology conferences to blister-packs of six hanging in the impulse aisle at Fry's.

She tried to imagine the technology conferences she'd been to with the addition of the subtitling and translation and couldn't do it. Not conferences. Something else. Kids' toy? Starbucks-smashing anti-globalists planning strategy before a WTO riot? She patted her pocket.

Rat-Toothed Freddy hissed and bubbled like a teakettle beside her, fuming. "What a cock," he muttered. "Thinks he's going to hire ten thousand teams to replace his workforce, doesn't say a word about what that lot is meant to be doing now he's shitcanned them all. Utter bullshit. Irrational exuberance gone berserk."

Andrea had a perverse impulse to turn the wand back on and splash Rat-Toothed Freddy's bilious words across the ceiling, and the thought made her giggle. She suppressed it and kept on piling up notes, thinking about the structure of the story she'd file that day.

Kettlewell pulled out some charts and another surfer in a suit came forward to talk money, walking them through the financials. She'd read them already and decided that they were a pretty credible bit of fiction, so she let her mind wander.

She was a hundred miles away when the ballroom doors burst open and the unionized laborers of the former Kodak and the former Duracell poured in on them, tossing literature into the air so that it snowed angry leaflets. They had a big drum and a bugle, and they shook tambourines. The hotel rent-a-cops occasionally darted forward and grabbed a protestor by the arm, but her colleagues would immediately swarm them and pry her loose and drag her back into the body of the demonstration. Rat-Toothed Freddy grinned and shouted something at Kettlewell, but it was lost in the din. The journos took a lot of pictures.

Andrea closed her PowerBook's lid and snatched a leaflet out of the air. WHAT ABOUT US? it began, and talked about the workers who'd been at Kodak and Duracell for twenty, thirty, even forty years, who had been conspicuously absent from Kettlewell's stated plans to date.

She twisted the laser-pointer to life and pointed it back at the wall. Leaning in very close, she said, "What are your plans for your existing workforce, Mr. Kettlewell?"

WHAT ARE YOUR PLANS FOR YOUR EXISTING WORKFORCE MR. KETTLEWELL

She repeated the question several times, refreshing the text so that it scrolled like a stock ticker across that upholstered wall, an illuminated focus that gradually drew all the attention in the room. The protestors saw it and began to laugh, then they read it aloud in ragged unison, until it became a chant: WHAT ARE YOUR PLANS -- thump of the big drum -- FOR YOUR EXISTING WORKFORCE thump MR. thump KETTLEWELL?

Andrea felt her cheeks warm. Kettlewell was looking at her with something like a smile. She liked him, but that was a personal thing and this was a truth thing. She was a little embarrassed that she had let him finish his spiel without calling him on that obvious question. She felt tricked, somehow. Well, she was making up for it now.

On the stage, the surfer-boys in suits were confabbing, holding their thumbs over their tie-mics. Finally, Kettlewell stepped up and held up his own laser-pointer, painting another rectangle with light beside Andrea's.

"I'm glad you asked that, Andrea," he said, his voice barely audible.

I'M GLAD YOU ASKED THAT ANDREA

The journalists chuckled. Even the chanters laughed a little. They quieted down.

"I'll tell you, there's a downside to living in this age of wonders: we are moving too fast and outstripping the ability of our institutions to keep pace with the changes in the world."

Rat-Toothed Freddy leaned over her shoulder, blowing shit-breath in her ear. "Translation: you're ass-fucked, the lot of you."

TRANSLATION YOUR ASS FUCKED THE LOT OF YOU

Andrea yelped as the words appeared on the wall and reflexively swung the pointer around, painting them on the ceiling, the opposite wall, and then, finally, in miniature, at her PowerBook's lid. She twisted the pointer off.

Rat-Toothed Freddy had the decency to look slightly embarrassed and he slunk away to the very end of the row of seats, scooting from chair to chair on his narrow butt. Kettlewell on stage was pretending very hard that he hadn't seen the profanity, and that he couldn't hear the jeering from the protestors now, even though it had grown so loud that he could no longer be heard over it. He kept on talking, and the words scrolled over the far wall.

THERE IS NO WORLD IN WHICH KODAK AND DURACELL GO ON MAKING FILM AND BATTERIES

THE COMPANIES HAVE MONEY IN THE BANK BUT IT HEMORRHAGES OUT THE DOOR EVERY DAY

WE ARE MAKING THINGS THAT NO ONE WANTS TO BUY

THIS PLAN INCLUDES A GENEROUS SEVERANCE FOR THOSE STAFFERS WORKING IN THE PARTS OF THE BUSINESS THAT WILL CLOSE DOWN

-- Andrea admired the twisted, long-way-around way of saying, "the people we're firing." Pure CEO passive voice. She couldn't type notes and read off the wall at the same time. She whipped out her little snapshot camera and monkeyed with it until it was in video mode and then started shooting the ticker.

BUT IF WE ARE TO MAKE GOOD ON THAT SEVERANCE WE NEED TO BE IN BUSINESS

WE NEED TO BE BRINGING IN A PROFIT SO THAT WE CAN MEET OUR OBLIGATIONS TO ALL OUR STAKEHOLDERS SHAREHOLDERS AND WORKFORCE ALIKE

WE CAN'T PAY A PENNY IN SEVERANCE IF WE'RE BANKRUPT

WE ARE HIRING 50000 NEW EMPLOYEES THIS YEAR AND THERE'S NOTHING THAT SAYS THAT THOSE NEW PEOPLE CAN'T COME FROM WITHIN

CURRENT EMPLOYEES WILL BE GIVEN CONSIDERATION BY OUR SCOUTS

ENTREPRENEURSHIP IS A DEEPLY AMERICAN PRACTICE AND OUR WORKERS ARE AS CAPABLE OF ENTREPRENEURIAL ACTION AS ANYONE

I AM CONFIDENT WE WILL FIND MANY OF OUR NEW HIRES FROM WITHIN OUR EXISTING WORKFORCE

I SAY THIS TO OUR EMPLOYEES IF YOU HAVE EVER DREAMED OF STRIKING OUT ON YOUR OWN EXECUTING ON SOME AMAZING IDEA AND NEVER FOUND THE MEANS TO DO IT NOW IS THE TIME AND WE ARE THE PEOPLE TO HELP

Andrea couldn't help but admire the pluck it took to keep speaking into the pointer, despite the howl and bangs.

"C'mon, I'm gonna grab some bagels before the protestors get to them," Rat-Toothed Freddy said, plucking at her arm -- apparently, this was his version of a charming pickup line. She shook him off authoritatively, with a whip-crack of her elbow.

Rat-Toothed stood there for a minute and then moved off. She waited to see if Kettlewell would say anything more, but he twisted the pointer off, shrugged, and waved at the hooting protestors and the analysts and the journalists and walked off-stage with the rest of the surfers in suits.

She got some comments from a few of the protestors, some details. Worked for Kodak or Duracell all their lives. Gave everything to the company. Took voluntary pay cuts under the old management five times in ten years to keep the business afloat, now facing layoffs as a big fat thank-you-suckers. So many kids. Such and such a mortgage.

She knew these stories from Detroit: she'd filed enough copy with varying renditions of it to last a lifetime. Silicon Valley was supposed to be different. Growth and entrepreneurship -- a failed company was just a stepping-stone to a successful one, can't win them all, dust yourself off and get back to the garage and start inventing. There's a whole world waiting out there!

Mother of three. Dad whose bright daughter's university fund was raided to make ends meet during the "temporary" austerity measures. This one has a Down's Syndrome kid and that one worked through three back surgeries to help meet production deadlines.

Half an hour before she'd been full of that old Silicon Valley optimism, the sense that there was a better world a-borning around her. Now she was back in that old rustbelt funk, the feeling that she was witness not to a beginning, but to a perpetual ending, a cycle of destruction that would tear down everything solid and reliable in the world.

She packed up her laptop and stepped out into the parking lot. Across the freeway, she could make out the bones of the Great America fun-park roller-coasters whipping around and around in the warm California sun.

These little tech-hamlets down the 101 were deceptively utopian. All the homeless people were miles north on the streets of San Francisco, where pedestrian marks for panhandling could be had, where the crack was sold on corners instead of out of the trunks of fresh-faced, friendly coke-dealers' cars. Down here it was giant malls, purpose-built dot-com buildings, and the occasional fun-park. Palo Alto was a university-town theme-park, provided you steered clear of the wrong side of the tracks, the East Palo Alto of slums that were practically shanties.

Christ, she was getting melancholy. She didn't want to go into the office -- not today. Not when she was in this kind of mood. She would go home and put her blazer back in the closet and change into yoga togs and write her column and have some good coffee.

She nailed up the copy in an hour and e-mailed it to her editor -- no e-mail-savvy newsrooms in Detroit! -- and poured herself a glass of Napa red (likewise, the local vintages in Michigan left something to be desired) and settled onto her porch, overlooking the big reservoir off 280 near Mountain View.

The house had been worth a small fortune at the start of the dot-boom, but now it was worth a large fortune and then some. She could conceivably sell this badly built little shack with its leaky hot-tub for enough money to retire on, if she wanted to live out the rest of her days in Sri Lanka or Nebraska.

"You've got no business feeling poorly, young lady," she said to herself. "You are as well set-up as you could have dreamt, and you are right in the thick of the weirdest and best time the world has yet seen. And Landon Kettlewell knows your name."

She finished the wine and opened her PowerBook. It was dark enough now with the sun set behind the hills that she could read the screen. The Web was full of interesting things, her e-mail full of challenging notes from her readers, and her editor had already signed off on her column.

She was getting ready to shut the lid and head for bed, so she pulled her mail once more.

From: kettlewell-l@skunkworks.kodacell.com

To: afleeks@sjmercury.com

Subject: Embedded journalist?

Thanks for keeping me honest today, Andrea. It's the hardest question we're facing today: what happens when all the things you're good at are no good to anyone anymore? I hope we're going to answer that with the new model.

You do good work, madam. I'd be honored if you'd consider joining one of our little teams for a couple months and chronicling what they do. I feel like we're making history here and we need someone to chronicle it.

I don't know if you can square this with the Merc, and I suppose that we should be doing this through my PR people and your editor, but there comes a time about this time every night when I'm just too goddamned hyper to bother with all that stuff and I want to just DO SOMETHING instead of ask someone else to start a process to investigate the possibility of someday possibly maybe doing something.

Will you do something with us, if we can make it work? 100 percent access, no oversight? Say you will. Please.

Your pal,

Kettlebelly

She stared at her screen. It was like a work of art; just look at that return address, "kettlewell-l@skunkworks.kodacell.com" -- for kodacell.com to be live and accepting mail, it had to have been registered the day before. She had a vision of Kettlewell checking his e-mail at midnight before his big press conference, catching Rat-Toothed Freddy's column, and registering kodacell.com on the spot, then waking up some sysadmin to get a mail server answering at skunkworks.kodacell.com. Last she'd heard, Lockheed-Martin was threatening to sue anyone who used their trademarked term "skunkworks" to describe a generic R&D department. That meant that Kettlewell had moved so fast that he hadn't even run this project by legal. She was willing to bet that he'd already ordered new business cards with the address on it.

There was a guy she knew, an editor at a mag who'd assigned himself a plum article that he'd run on his own cover. He'd gotten a book-deal out of it. A half-million dollar book-deal. If Kettlewell was right, then the exclusive book on the inside of the first year at Kodacell could easily make that advance. And the props would be mad, as the kids said.

Kettlebelly! It was such a stupid frat-boy nickname, but it made her smile. He wasn't taking himself seriously, or maybe he was, but he wasn't being a pompous ass about it. He was serious about changing the world and frivolous about everything else. She'd have a hard time being an objective reporter if she said yes to this.

She couldn't possibly decide at this hour. She needed a night's sleep and she had to talk this over with the Merc. If she had a boyfriend, she'd have to talk it over with him, but that wasn't a problem in her life these days.

She spread on some expensive duty-free French wrinkle-cream and brushed her teeth and put on her nightie and double-checked the door locks and did all the normal things she did of an evening. Then she folded back her sheets, plumped her pillows and stared at them.

She turned on her heel and stalked back to her PowerBook and thumped the spacebar until the thing woke from sleep.

From: afleeks@sjmercury.com

To: kettlewell-l@skunkworks.kodacell.com

Subject: Re: Embedded journalist?

Kettlebelly: that is one dumb nickname. I couldn't possibly associate myself with a grown man who calls himself Kettlebelly.

So stop calling yourself Kettlebelly, immediately. If you can do that, we've got a deal.

Andrea

There had come a day when her readers acquired e-mail and the paper ran her address with her byline, and her readers had begun to write her and write her and write her. Some were amazing, informative, thoughtful notes. Some were the vilest, most bilious trolling. In order to deal with these notes, she had taught herself to pause, breathe and re-read any e-mail message before clicking send.

The reflex kicked in now and she re-read her note to Kettlebelly -- Kettlewell! -- and felt a crimp in her guts. Then she hit send.

She needed to pee, and apparently had done for some time, without realizing it. She was on the toilet when she heard the ping of new mail incoming.

From: kettlewell-l@skunkworks.kodacell.com

To: afleeks@sjmercury.com

Subject: Re: Embedded journalist?

I will never call myself Kettlebelly again.

Your pal,

Kettledrum.

Oh-shit-oh-shit-oh-shit. She did a little two-step at her bed's edge. Tomorrow she'd go see her editor about this, but it just felt right, and exciting, like she was on the brink of an event that would change her life forever.

It took her three hours of mindless Web-surfing, including a truly dreary Hot-Or-Not clicktrance, before she was able to lull herself to sleep. As she nodded off, she thought that Kettlewell's insomnia was as contagious as his excitement.

Shares