Hunter S. Thompson never actually said that "the music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs." The quip, from Thompson's 1988 "Generation of Swine: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the '80s," was in fact meant to describe the TV business.

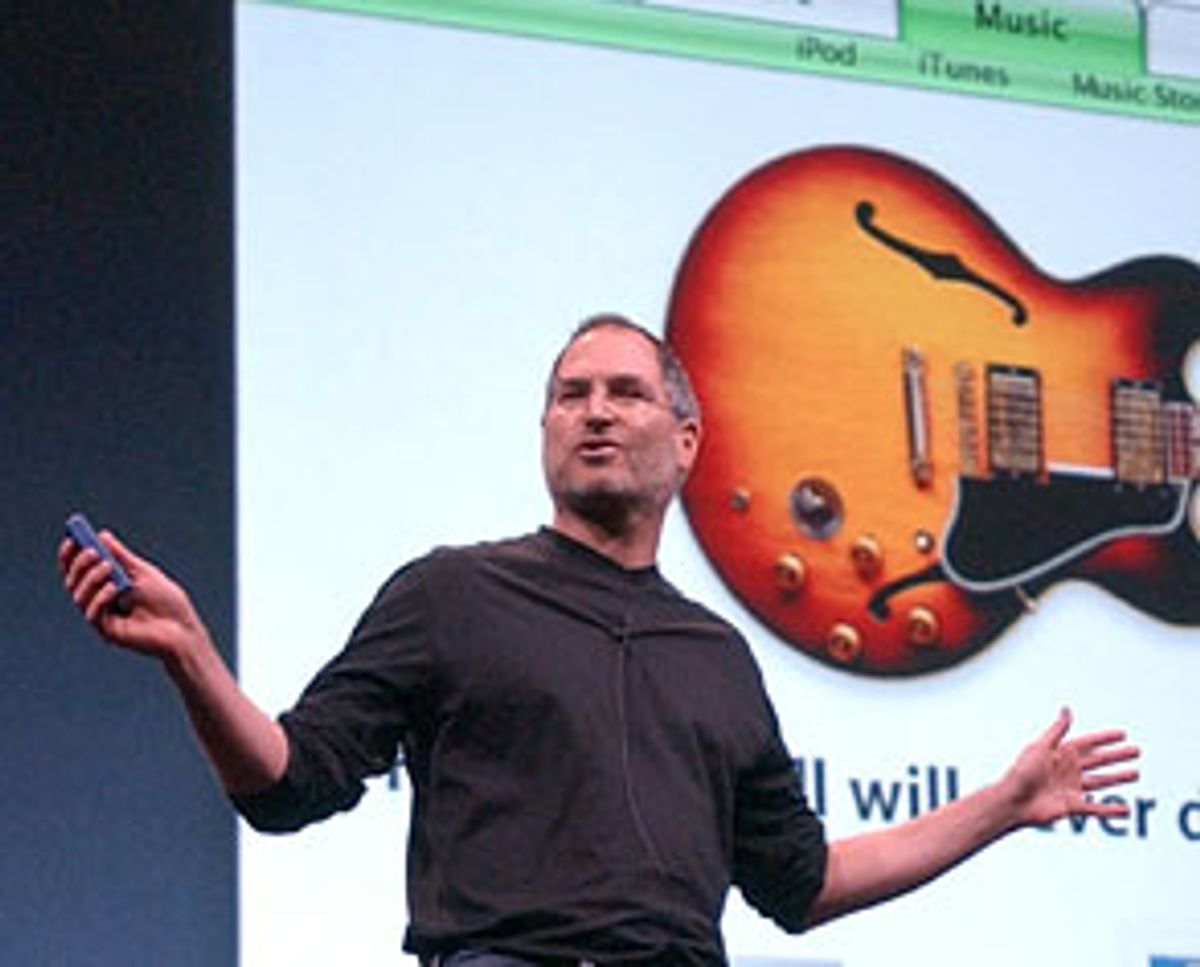

But in a post-Napster world, one in which both musicians and music lovers have come to harbor a deep animosity toward record labels, the Thompson misquote has taken on the patina of truth -- which is why, in his introduction of a new online music-buying service on Monday in San Francisco, Apple CEO Steve Jobs elicited a rousing response by flashing the quote up on the giant video screen behind him. Probably the only folks in the room who weren't applauding were the industry executives in attendance, but they, too, might have been OK with Jobs' insults. Indeed, the execs ought to have been pleased with Apple's geek-chic CEO: That's because Jobs is being nice enough to save the music business from itself.

The music service Jobs unveiled is a delight. Called the iTunes Music Store, the service -- it's available only on Apple machines for now but will be ready for Windows "by the end of the year" -- is fully integrated into the company's jukebox software. Users can search for songs to purchase in the same way they'd look for songs they already have on their machines. The system is foolproof: You type in a name, a song comes up, and you press a button to buy it. That's it. You're in the hole for 99 cents for each song you download ($10 for each album), but you see none of the transaction details; all the purchases are "one-click." And here's the stunning thing: Once you've bought a song, you own it. You can do (pretty much) whatever you want to do with the songs you download, including burning them to CDs, transferring them to iPods, or sending them to other Macs.

Forgive me if the above sounds like a paid-for marketing pitch for Apple, but anyone who's familiar with the recent battles between the music and tech industries should be amazed that something like Apple's service ever came about. Many online music services are on the market, but they've all done poorly, most likely because, as Jobs said, they all "treat you like a criminal." For the most part, the other services are subscription based -- users pay a $10 or $20 per-month fee for access to a catalog of songs, and they must put up with a Byzantine set of rules outlining how they can use the tracks. Some services only offer "streaming" music, meaning that you have to be connected to the Internet when you want to listen to your songs; others let you download songs so long as you play them on a single machine (forget about transferring them to portable MP3 players); a few services let you burn songs to CDs, but only for selected tracks for an extra per-song fee. The worst part is, you have to keep paying to get the music; once you cancel your subscription, you can no longer listen to many of the tracks you've downloaded.

One can't fault the subscription services for their poor offerings -- the blame goes straight to the record labels, which have dragged their feet for years in offering workable licensing terms for online distribution. The industry, scared of spawning other Napsters, usually allows music online only with a host of restrictions curbing its use. For instance, Warner Music recently licensed Madonna's songs to pay services only on the condition that the companies sell full-length albums, and not selected Madonna tracks -- something that many of the services can't even technically accomplish.

In this light, Apple's service is best thought of not as a technological breakthrough but as a psychological one. The product is clearly the result of what must have been tough negotiations between Apple and the labels -- and in the end, Steve Jobs seems to have convinced music execs of the folly of their ways. How did he do it? Dealing with the music industry, Jobs explained in his press conference, was not easy. A year and a half ago, when he came up with a plan to offer an easy way to buy digital music online, he didn't know whether anyone in music would see things his way. The industry was going after Napster and other file-trading services in the courts, and they were pushing draconian legislation in Washington. But when he met with the labels, Jobs found many executives who shared his passion to "change the world," and according to some reports, Jobs personally negotiated with key artists to get them to let their music go online. By Monday, Apple had struck "landmark" licensing deals with the five biggest music companies, and it garnered the blessing of no less a critic of the tech industry than Hilary Rosen, the head of the Recording Industry Association of America. "The Apple system has the potential to do for music sales what the Walkman did for the cassette," Rosen told the New York Times on Monday.

But now that the music business appears to have changed its tune, it's time to see whether listeners, who have so far shown no qualms in stealing their music from file-trading services, will accept the righteous path. For years, critics of the music business have said that once customers are offered a reasonable alternative to stealing, they'll gladly embrace it -- now we'll find out if these people are right. Fans of file-traders will find much to like in the new Apple system. The downloading is hassle free -- you won't have to worry about songs that never come through, as is common on peer-to-peer systems like Kazaa and Gnutella, or programs chocked with adware and spyware. Apple uses the AAC music format, which sounds better than MP3, and some of the songs it offers are encoded straight from the master tapes, Jobs said, which means the tracks will be of better quality than the comparable CD. You won't find that on Morpheus.

Perhaps even more compelling -- users of free services are increasingly exposed to legal action by the recording industry. Recently, in separate cases, federal judges have ruled that it's perfectly legal for companies like Morpheus to run file-traders, but that ISPs (like Verizon) must turn over to the music industry the names of people who use these services -- taken together, these rulings give the music business an increased incentive to sue people who trade on such services rather than the people who build such services. If you're offering files up on Grokster, you'd better have a good lawyer.

Still, there are some reasons people won't immediately quit using the free services to switch to Apple's service, the most important of which is the catalog size. Apple will start off with only about 200,000 songs in its store. This is a huge number, and the company has exclusive online rights to many artists (including Eminem, Alicia Keys and Bob Dylan), but far more songs are still available for free on file-trading services.

Because Apple's service doesn't require a subscription, though, its catalog size might not be much of a problem. For a while, people will probably just use both the Apple service and the free services, putting up with the frustrations of something like Kazaa only when the song they're looking for isn't available in iTunes. You can see how this scenario could prompt many labels to release more and more of their songs to Apple: If giving your song to the Apple store will reduce the number of people who steal it, why wouldn't you want your song on the shelf?

Except for some well-paid congressmen, nobody likes the music industry anymore. In the public imagination, the companies that brought us the Beatles and Madonna are about as trustworthy as those that bring us tobacco and firearms. Jobs' new service might change that. Finally, it'll be possible to listen to music as Napster promised -- without the worries, without the frustrations, as music was meant to be enjoyed. If it takes off, the system -- and the clones of it that will surely follow -- could significantly boost the record labels' bottom line, and Apple would certainly benefit as well.

And down the road, perhaps, music itself will change. If tracks are sold one by one, can the death of the full-length album be far off? (The CD, as a physical medium, surely can't last the decade.) What will happen to top-40 radio? If innovative indie stars enjoy as much access to your desktop as sultry teenagers, will we ever have to listen to sugary pop again?

These are the sorts of questions everyone asked when Napster came along, and we never quite got our answers. Perhaps, now, we'll finally see what the future has in store for us.

Shares